1. Background

Excessive fat accumulation is a characteristic of obesity and is influenced by a number of factors such as genetics, behavioral patterns, or environment (1). Based on estimates, 206 million people aged 5 - 19 years will be living with obesity in 2025 (2). The well-being of children and their families may be affected by obesity, and the health consequences of childhood obesity are significant (3). The risk factors for childhood obesity include genetic, environmental, and neighborhood factors (4).

Childhood obesity has widespread and lasting adverse consequences, including emotional disorders (5). Depression and anxiety symptoms are more likely to occur in overweight/obese children than in peers without overweight/obesity (6). On the other hand, it seems that as the BMI level increases, negative affect (NA) scores also increase (7). The NA refers to a group of negative emotional states, including anxiety, depression, stress, etc. (8).

Previous studies have indicated that self-criticism is considered to play significant roles in eating behaviors (9) and is a predictor of eating disorder dimensions (10). Shame is also a negative reaction associated with obesity (11). People who are obese are stigmatized both by society and by their surroundings, and stigma also creates shame, which can affect how obese people view and perceive themselves (12). Duarte et al. (13) showed that perceived shame and self-criticism of inferiority can play a significant role in the self-regulation of eating behavior in overweight people who try to control their weight.

Recently, a unified protocol (UP) for the transdiagnostic treatment has gained attention in different populations (14). The UP is a cognitive behavioral intervention targeting emotion dysregulation, which underlies all anxiety, depression, and related disorders (15) and is designed to address neuroticism by teaching adaptive emotion regulation skills (16). Neuroticism is positively related to negative affect (17) and shame (18). On the other hand, neuroticism predicts self-criticism (19).

The results of Farchione et al.'s study indicated that unified transdiagnostic therapy leads to improvement in negative affect symptoms (14). Moreover, many studies have confirmed the effectiveness of this treatment on emotional disorders, including anxiety and depression (20-22).

Negative effects and the difficulty of controlling emotions are among the factors that can be effective for obesity, as mentioned above. Considering the high prevalence of obesity in children and its unpleasant consequences, it is necessary to take measures to prevent and treat it. One of the interventions that has been effective in the field of emotion regulation is unified transdiagnostic therapy. The effectiveness of this treatment in the field of childhood obesity has not been studied so far.

2. Objectives

The objective of the current study is to investigate the effectiveness of UP on negative effects, shame, and self-criticism in obese children.

Hypotheses: (1) Unified transdiagnostic therapy reduces negative affect in obese children; (2) unified transdiagnostic therapy reduces shame in obese children; (3) unified transdiagnostic therapy reduces self-criticism in obese children.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Procedure

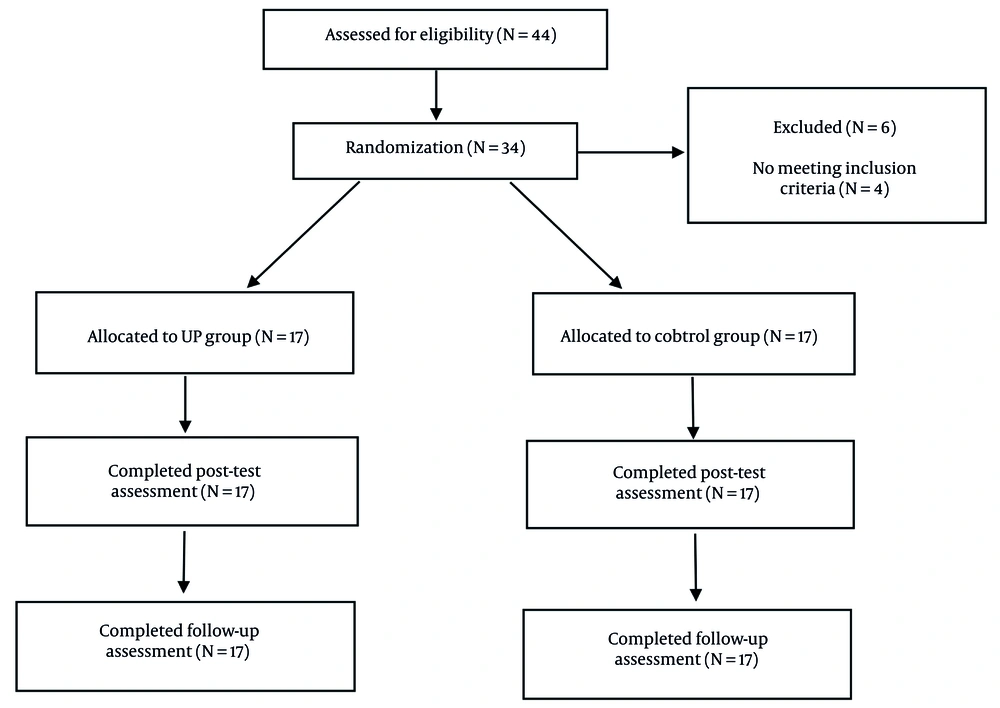

In this study, a randomized controlled and single-blind design was employed to assess the effectiveness of unified transdiagnostic treatment. Initially, adequate arrangements were made with the Education Department in Isfahan province, and children whose overweight condition was diagnosed by an endocrinologist and who met other inclusion criteria were included in the study. Informed consent was acquired from their parents or legal guardians to participate in the study. Simple randomization was used for the randomization process. The website https://www.Randomization.com was used online for random allocation, and an impartial researcher performed the randomization process without any knowledge or involvement in the treatment. The sampling process occurred between August and November 2022, while the implementation of the intervention took place from January to March 2023. Participants were split into the following two groups, based on the sequence of enrollment in the study: Ratio 1:1 UP group: Control group. In the present study, the convenience sampling method was used. In total, 44 obese children were included in the study and were considered eligible. Ten participants declined participation. Subsequently, 34 participants were randomly allocated to intervention and control waiting lists.

Participants in the intervention group received 8 sessions of UP. In contrast, no therapy was provided to those on the waiting list; they only received the UP intervention after completing data collection. A set of study questionnaires was completed by participants in person prior to treatment, immediately following the treatment phase, and at follow-up 2 - 4 months later. The research data was analyzed by a researcher who was not involved in delivering the treatment.

3.2. Participants

The participants of this study were obese and overweight children. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Age range from 7 to 15 years, (2) obesity and overweight (BMI > 95), (3) not receiving psychological services outside the treatment session, (4) having primary education, (5) completing the informed consent form, and (6) parents not receiving psychological care outside of treatment. Exclusion criteria for children included parents' dissatisfaction with the child's attendance at therapy sessions and participation in treatment programs related to a treatment method.

3.3. Sample Size

G*Power was used to determine the study sample size. With an effect size of 0.45, an alpha of 0.05, and a power of 0.8, a total of 44 respondents in two equally sized groups were needed (23). Trial data are listed in Figure 1.

3.4. Instruments

3.4.1. External Shame Scale

It was developed in 1994 by Goss et al. and is an eighteen-item measure designed to evaluate external shame (24). It is adapted to measure external shame from Cook's Internalized Shame Scale and is rated on a five-point scale, according to the frequency with which one evaluates how others judge oneself (0 = never to 4 = almost always) (24). Questions 1, 3, 5, and 6 assess external shame, while questions 2, 4, 7, and 8 evaluate internal shame. The scoring range is from 0 to 32, with higher scores indicating greater levels of shame (25). Cronbach's alpha values for the whole scale and the factors of feelings of inferiority, feelings of emptiness, and shame about making mistakes were 0.93, 0.92, 0.71, and 0.75, respectively (26). This scale is a concise, dependable, and valuable tool for research, educational, and clinical settings involving adolescents of school age (27).

3.4.2. Levels of Self-criticism Scale

This scale was used to measure comparative self-criticism (CSC) and internal self-criticism (ISC), and its final scale includes 22 items. For CSC and ISC, the reliability of this scale with Cronbach's alpha coefficients is 0.81 and 0.87, respectively (28). Participants respond to each item using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very well). The total score is calculated by summing the responses across all items (28). In the Iranian sample, Cronbach's alpha for the self-criticism levels was 0.88 for the self-criticism subscale of comparisons and 0.89 for ISC (29). This scale has been used in a pediatric population, and acceptable internal consistency has been reported (30).

3.4.3. Positive and Negative Affect Scale

The PANAS was developed by Watson et al. (31). This scale is composed of 20 items, with 10 items for each positive and negative affect, and has a five-point Likert scale (32). This scale is designed to measure affects in the present moment as well as in the past (33). The reliability of the PA subscale ranged from 0.86 to 0.90, and the NA subscale from 0.84 to 0.87 (34). In the Persian version of this scale, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.85 for the main scale (35). In the present study, the parent version of this questionnaire was used. The PANAS-C has 27 items, and the total score is calculated by summing the responses across all items. It has recently demonstrated strong psychometric support in a school sample of 606 children and adolescents (36).

3.5. Intervention

Participants attended 8 face-to-face sessions based on Barlow's integrative diagnostic therapy book. Therapy sessions were conducted by a trained psychologist. The details of the sessions are listed in Table 1.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1. Motivational interview to motivate and strengthen patients' motivation for change; providing goals and logic of the treatment | In this session, the therapist encourages and motivates the patients. Also tries to make self-efficacy and believe in the ability to change and successful treatment in the patients. Using the scales worksheet, the authorities try to assess the profit and loss of changing or staying in the current situation. The therapist and patients also determine therapeutic goals by the treatment goal setting sheet and the practical steps to achieve the goals. |

| 2. Recognizing the formation and continuation of emotions through education | During this session, some key assumptions are presented to the patient, including the emotional nature, the emotional experience, and the concept of the learned and safe reactions. It is expected that patients can be adequately trained by reviewing dominant emotional response patterns to events, triggers, adaptive functioning, and severe persistence factors. |

| 3. Accepting and awareness of emotions by teaching emotional awareness and learning to observe emotional experiences (emotions and reaction to emotions) by mindfulness | During these two sessions, the clients are provided insights on recognizing and reacting to emotions to gain awareness without judgment and evaluation by focusing on the present moment. These skills are developed through mindfulness exercises through the forms of "conscious attention to the present moment without judgment", "emphasis on the present moment", and "reconsider the emotions and behaviors resulting from an emotion at the moment". |

| 4. Evaluation; cognitive re-evaluation as well as creating insight into the impact of the interaction between thoughts and emotions | During this session, clients are trained to evaluate thoughts and them interaction with emotions and identify automatic thoughts and common cognitive distortions such as negative prediction and catastrophizing. Clients also learn to increase their flexibility and correct negative thoughts in different situations by considering negative spontaneous thoughts. At the end of this session, the clients are expected to gain a deeper insight into the evaluation and interpretation of situations. The tools used in this session are the downward arrow technique and identifying and measuring negative spontaneous thoughts. |

| 5. Familiarity with strategies to avoid emotions and the effects of these strategies | During this session, the focus is on the behavioral reactions resulting from emotional experiences. The client identifies avoidance patterns with the therapist’s help and then tries to correct the avoidance reaction and replace it with a more appropriate response. A worksheet of emotion avoidance strategy will be used in this session. |

| 6. Increased awareness and tolerance of physical emotions | At this stage of treatment, an attempt is made to make the client aware of the importance of physical emotions in various experiences. After identifying provocative situations, the therapist tries to design situations like reality, motivate physical emotions in the client, and encourage the client to confront them. The goal is to raise the threshold of emotion tolerance and create an atmosphere where the patient understands the interaction of emotions and thoughts. |

| 7. Dealing with emotions in the situation and presenting the logic of confrontation; learning to compile a list of hierarchy of stressful situations and design coping exercises | Considering the importance of shared emotions in the etiology and persistence of emotional disorder, special emphasis is placed on confronting the triggers, stimulating internal and external excitement during these sessions. Once the client and therapist have compiled a list of excitement-provoking situations and identified the hierarchy of fear in each situation, the client will gradually confront the situations. Depending on the anxiety scale, these encrustations can be visual or reality during or outside the session. Before the confrontation, the therapist explains the logic of the encounter and its barriers to the client; this allows the client to respond to emotions more efficiently while anticipating possible events. During these sessions, clients are helped to apply the skills learned during treatment, such as relaxation exercises and mindfulness, to facilitate the treatment process and remove obstacles. |

| 8. Prevention of recurrence | In the final session, clients are taught strategies to anticipate potential problems and thus perpetuate the benefits of treatment; general concepts are reviewed, and therapeutic progress is discussed and summarized. |

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Finally, questionnaires were collected, and research data were analyzed using SPSS-24 software, employing descriptive statistics (i.e., mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (including MANCOVA).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Data

This study was agreed to by around 44 overweight children. Of all the children (N = 44) who started the program, 34 children finished it, and 10 participants dropped out. The children’s mean age in the experimental and control groups was 10.58 and 10.50, respectively. Their mean BMI and weight in the experimental group were 25.06 and 57.58, respectively, and in the control group were 25.78 and 57.94.

According to Table 2, the mean scores of the experimental group in all variables during the three stages of post-test, follow-up 1, and follow-up 2 showed a decreasing trend, but there were no noticeable changes in the control group. In the experimental group, the values of the Shapiro-Wilks test for the variables of negative affect, shame, and CSC are not significant in the four stages of the test. In the control group, the values of this test for negative affect and self-criticism in follow-up 2, for shame in the four stages of the study, and for internalized self-criticism and CSC in follow-up 1 and 2 are not significant (P > 0.05). Therefore, it can be concluded that the distribution of the scores of the research variables in these stages is normal.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Shapiro-Wilk Test | Levene Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | P-Value | F | df | P-Value | ||

| Negative affect | ||||||

| UP | ||||||

| Pre | 33.47 ± 3.95 | 0.95 | 0.52 | 1.42 | 1 | 0.24 |

| Post | 26.88 ± 3.67 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.071 | 1 | 0.79 |

| Follow1 | 26.47 ± 3.76 | 0.93 | 0.29 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.96 |

| Follow2 | 24.94 ± 3.79 | 0.92 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 1 | 0.54 |

| Control | ||||||

| Pre | 31.58 ± 2.71 | 0.85 | 0.011 | |||

| Post | 30.64 ± 3.40 | 0.87 | 0.024 | |||

| Follow1 | 30.88 ± 3.77 | 0.90 | 0.002 | |||

| Follow2 | 30.88 ± 3.75 | 0.95 | 0.57 | |||

| Shame | ||||||

| UP | ||||||

| Pre | 61.11 ± 6.08 | 0.92 | 0.16 | 0.57 | 1 | 0.45 |

| Post | 50.94 ± 4.90 | 0.95 | 0.52 | 2.58 | 1 | 0.11 |

| Follow1 | 49.11 ± 5.51 | 0.95 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 1 | 0.48 |

| Follow2 | 50.05 ± 5.40 | 0.95 | 0.61 | 1.88 | 1 | 0.18 |

| Control | ||||||

| Pre | 61.64 ± 7.65 | 0.97 | 0.94 | |||

| Post | 60.29 ± 7.58 | 0.98 | 0.97 | |||

| Follow1 | 62.35 ± 6.97 | 0.98 | 0.95 | |||

| Follow2 | 61.70 ± 7.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||

| Self-criticism | ||||||

| UP | ||||||

| Pre | 84.23 ± 6.75 | 0.87 | 0.024 | 0.061 | 1 | 0.80 |

| Post | 75.29 ± 5.66 | 0.82 | 0.005 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.32 |

| Follow1 | 73.88 ± 6.85 | 0.86 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.97 |

| Follow2 | 73.17 ± 9.61 | 0.82 | 0.004 | 0.32 | 1 | 0.57 |

| Control | ||||||

| Pre | 85 ± 7.12 | 0.84 | 0.010 | |||

| Post | 82.94 ± 6.51 | 0.87 | 0.024 | |||

| Follow1 | 82.76 ± 7.20 | 0.89 | 0.061 | |||

| Follow2 | 84 ± 8.09 | 0.91 | 0.12 | |||

| Internal self-criticism | ||||||

| UP | ||||||

| Pre | 38.70 ± 4.02 | 0.87 | 0.024 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.58 |

| Post | 34.82 ± 3.82 | 0.82 | 0.005 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.58 |

| Follow1 | 33.94 ± 3.79 | 0.86 | 0.016 | 0.78 | 1 | 0.38 |

| Follow2 | 33.23 ± 4.16 | 0.82 | 0.004 | 0.49 | 1 | 0.48 |

| Control | ||||||

| Pre | 39.23 ± 4.88 | 0.84 | 0.010 | |||

| Post | 38.82 ± 4.50 | 0.87 | 0.024 | |||

| Follow1 | 38.29 ± 4.75 | 0.89 | 0.016 | |||

| Follow2 | 37.76 ± 4.82 | 0.91 | 0.12 | |||

| Comparative self-criticism | ||||||

| UP | ||||||

| Pre | 45.52 ± 4.55 | 0.89 | 0.066 | 0.032 | 1 | 0.85 |

| Post | 40.47 ± 4.34 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.30 | 1 | 0.29 |

| Follow1 | 39.94 ± 5.36 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 0.055 | 1 | 0.81 |

| Follow2 | 38.70 ± 4.93 | 0.91 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 1 | 0.36 |

| Control | ||||||

| Pre | 45.76 ± 4.36 | 0.85 | 0.013 | |||

| Post | 44.11 ± 4.75 | 0.82 | 0.005 | |||

| Follow1 | 44.47 ± 5.50 | 0.91 | 0.14 | |||

| Follow2 | 44.94 ± 6.36 | 0.97 | 0.86 | |||

Descriptive Statistics Related to the Variables of Negative Affect, Shame, and Self-criticism in the Pre-test and Post-test of the Group

It should be noted that in the experimental group, the values of this test for shame in the four stages of the test, and for self-criticism in the four stages of the test in the control group, are significant for the variables of negative affect and self-criticism in pre-test, post-test, and follow-up 1, and for self-criticism, internalized self-criticism, and CSC in pre-test and post-test (P < 0.05). Therefore, it can be concluded that the distribution of scores in these variables in the mentioned stages is not normal. However, given that the sample size is equal, F is resistant to violations of parametric assumptions.

Before the analysis of covariance test, in order to comply with the assumptions of the analysis of covariance, Levene’s test was performed to check the equality of variances. The results of Levene’s test showed that the equality of variances for the variables was established (P < 0.05).

Bax’s M test was used to assess the homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices. In the variable of self-criticism and the subscale of CSC, the P-value is greater than 0.05, so the assumption of the same covariance between scores in these variables is established. However, in the variables of negative emotion, shame, and internalized self-criticism, the P-value is smaller than 0.05, so the assumption of covariance similarity between scores is not established. Nonetheless, because the sample size is equal, F is resistant to the violation of parametric assumptions. The results are shown in Table 3.

| Variables | Bax’s M | F | df 1 | df 2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect | 25.91 | 2.23 | 10 | 4895.61 | 0.013 |

| Shame | 24.27 | 2.09 | 10 | 4895.61 | 0.022 |

| Self-criticism | 11.22 | 0.96 | 10 | 4895.61 | 0.46 |

| Internal self-criticism | 32.20 | 2.78 | 10 | 4895.61 | 0.002 |

| Comparative self-criticism | 16.83 | 1.45 | 10 | 4895.61 | 0.15 |

The Results Related to the Assumption of the Same Covariance Between the Two Groups in the Pre-test, Post-test, and Follow-up Stages 1 and 2 in the Research Variables

Based on Table 4, unified transdiagnostic therapy on negative affect, shame, and self-criticism is statistically significant. In other words, unified transdiagnostic therapy has been effective on negative affect, shame, self-criticism, and its subscales in the experimental group compared to the control group in the post-test and follow-up phase (P < 0.001). The amount of this effect in the implementation of the test for negative affect is equal to 0.83, for shame is equal to 0.80, for self-criticism is equal to 0.56, for internalized self-criticism is equal to 0.84, and for CSC is equal to 0.44.

| Variables | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | P-Value | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect | |||||||

| Test | 990.871 | 1 | 990.871 | 160.160 | 0.000 | 0.838 | 1 |

| Error | 191.790 | 31 | 6.187 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Shame | |||||||

| Test | 3065.618 | 1 | 3065.618 | 125.638 | 0.000 | 0.802 | 1 |

| Error | 756.412 | 31 | 24.400 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Self-criticism | |||||||

| Test | 1837.270 | 1 | 1837.270 | 39.842 | 0.000 | 0.562 | 1 |

| Error | 1429.542 | 31 | 46.144 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Internal self-criticism | |||||||

| Test | 990.871 | 1 | 990.871 | 160.160 | 0.000 | 0.838 | 1 |

| Error | 191.790 | 31 | 6.187 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Comparative self-criticism | |||||||

| Test | 533.281 | 1 | 533.281 | 24.559 | 0.000 | 0.442 | 1 |

| Error | 673.133 | 31 | 21,714 | - | - | - | 1 |

Results of Covariance Analysis of the Effect of Unified Transdiagnostic Therapy on Negative Affect, Shame, and Self-criticism

5. Discussion

The aim of this trial is to explore the effectiveness of UP on negative affect, shame, and self-criticism in obese children. This research is consistent with a study conducted by Farchione et al., which demonstrated that UP leads to a significant improvement in negative and positive affects (14). The unified transdiagnostic treatment is a method used to improve emotion regulation skills (37). On the other hand, emotion regulation skills such as distraction, as well as cognitive reappraisal and acceptance, have an effect on positive and negative affects in adolescents (38). Consequently, effective emotion regulation strategies can be used to influence negative affects in this treatment.

The effectiveness of this intervention in reducing shame and self-criticism has also been shown by the study. The results of Naeimijoo et al.'s study indicated that this treatment significantly reduced body shame and self-criticism (39). Since one of the modules of this protocol is mindfulness, and mindfulness interventions have an effect on shame, it can be said that the effectiveness of unified transdiagnostic treatment on shame in obese children is through the mindfulness module (40). Also, the findings show that interventions based on mindfulness are effective on self-criticism (41-43), and considering that one of the unified transdiagnostic treatment modules is the mindfulness module, it can be said that with training in the present moment and self-compassion, this treatment is effective in reducing self-criticism in obese children.

On the other hand, another module used in this treatment teaches the person to evaluate thoughts and their interaction with emotions, and to identify automatic thoughts and common cognitive distortions such as negative predictions and catastrophizing. Since cognitive distortions can be related to shame and self-criticism, this seems to be another reason why unified transdiagnostic therapy is effective on shame and self-criticism.

The study has some limitations due to its preliminary nature. The sample size was small, which might prevent us from detecting significant differences in some analyses. Due to the small sample size, the findings of this study have limited generalizability, and it is recommended to replicate this study in the future with larger samples. Secondly, most of the measures in this study have been self-reported. Addressing this issue could be a crucial aspect for future studies. Thirdly, the study population was limited to the schools of one province and could not be generalized to other cities. Therefore, this study did not avoid known biases associated with the use of self-reporting methods.

Conclusion: In sum, the current study presents preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of UP on negative effects, shame, and self-criticism in obese children. Further studies based on replication are needed for the present results. To better understand how these results are obtained, more work is needed in the future. Lastly, it is recommended that the results of treatment with Transdiagnostic be followed up for a period of time.