1. Background

Studies have revealed that families of Chronic mental disorders experience significant stress, endure arduous responsibilities (1), and report numerous challenges: Stigma and shame from being blamed for the illness, managing the symptoms of mental disorders, economic difficulties, distressing behaviors, social isolation, lack of social support, and other common issues in families with chronic mental disorders (2). Conversely, if these families are left without treatment or intervention, inadequate patient care, neglect, worsening homelessness among chronic mental disorders, and increased relapse and rehospitalization rates may result (3). Therefore, the research underscores the urgent need for training on effective coping strategies and providing psychological support through counseling or group therapy for families of chronic mental disorders (4). Contemporary psychotherapy approaches often adopt a medical-centered perspective, focusing on dominance, control, elimination, and suppression of all symptoms (5). The modern healing perspective assumes that "Each of us is a Messiah of a world (of people): In our hands is a medicine for every pain" (6). Physicians regard themselves as healers of the world, believing their actions alone suffice to solve problems and cure diseases, relying solely on their knowledge and dismissing the divine will. Consequently, God reveals their inability and limitations in addressing illnesses, as elucidated through the teachings of Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi (672 AH). "In their arrogance they did not say, “If God will” therefore God showed unto them the weakness of Man" (6). Since physicians rely solely on their skill and expertise, disregarding the omnipotent divine will that transcends worldly causes, as Hafez eloquently stated: "Relying solely on piety and knowledge in the path is heresy, even if the seeker possesses a hundred skills, trust in God is still required" (7). Trust in God is defined as expressing one's helplessness, trusting in another, and entrusting one's affairs to a reliable individual due to their competence or one’s own inability to handle the matter independently. In essence, trust in God in matters to God and submitting to His wisdom and decisions is called trust in God. This is substantiated by the Quranic verse: "Whoever puts their trust in God, He is sufficient for them" (Quran, Sura At-Talaq, Verse 3) (8). However, this does not imply abandoning effort and endeavor. It seems that under the transformative light of spirituality, particularly trust in God, the psychological burdens arising from caregiving responsibilities can be alleviated. In this regard, one of the interventions that appears capable of fostering trust in God is meaning therapy. The therapy through meaning or healing through meaning is often associated with Victor Emil Frankl (1905 - 1997). However, upon closer examination, the essence of this approach can also be discerned within the profound insights of Islamic-Iranian mysticism, particularly in the elevated thoughts of Mawlana Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi (672 AH). Rumi, a preeminent teacher of meaning and an explorer of its depths, placed meaning at the core of his philosophy and actions, inviting everyone to do the same. Rumi described himself as a fish that never tires of the water of meaning (9). In the review of the research background, the results of several studies have indirectly shown that meaning therapy impacts trust in God, faith, and attachment to God in various groups (10). Zamani Foroushani (11), in a study on the effectiveness of group counseling with a meaning therapy approach on trust in God and attachment to God among orphaned male students, concluded that meaning therapy could enhance trust in God in individuals. Amirloo and Naderi (12) conducted a study titled "the effect of logotherapy training on mental image of God, death anxiety, and religiousness among secondary school students in Ahvaz city". Their results showed that meaning therapy training significantly impacted the mental image of God (13), in a study on the relationship between attachment to God and meaningfulness in life among teachers, demonstrated a significant and positive correlation between attachment to God and meaningfulness in life (P < 0.001).

2. Methods

This quasi-experimental study employed a pretest-posttest control group design. The statistical population consisted of all families of patients with chronic mental disorders with a family member hospitalized in the rehabilitation and care institution Tavan Behbode Taba (Varmanjeh) in Kermanshah, Iran 2024. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran (IR.KUMS.REC.1400.630). Based on Cohen's model (14), a sample size of 32 participants was estimated, drawn from family members of patients with chronic mental disorders. Of these, 16 individuals were randomly assigned to the experimental group to participate in the educational program, while the remaining 16 individuals, who did not participate in the educational program, were randomly assigned to the control group. The random allocation was done based on a block randomization procedure with size 4, by a random number generator. All measures were recorded at the beginning and 2 weeks after the study. Inclusion criteria: Age between 18 and 60 years, minimum educational level of middle school, absence of prior psychotherapy or chronic mental medication within six months before entering the educational program, and signing an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria: Lack of willingness to continue participation in the educational program sessions, incomplete questionnaires.

2.1. Research Instruments

2.1.1. Trust in God Scale

The trust in God Scale, developed by Arefian and Taghavi (15), was designed based on Quranic and mystical texts. This questionnaire consists of 16 four-option items, scored using a 5-point Likert scale. The test-retest correlation coefficient over a two-week interval was 0.78, and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the entire sample was 0.82 (P < 0.001), indicating high reliability. Construct validity was assessed by examining the correlation between the scores on this questionnaire and a gratitude questionnaire, yielding a correlation coefficient of 0.55 (P < 0.001). This indicates that higher trust in God correlates with greater gratitude. Overall, the trust in God Scale demonstrates robust psychometric properties and is suitable for use in Iran (15).

2.1.2. Meaning Therapy Educational Program Based on Rumi's Teachings

This educational program was developed by aligning the theoretical foundations of Frankl’s meaning therapy with the meaning-focused teachings of Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi (672 AH). Ultimately, the meaning-centered therapy program based on Rumi's teachings, as detailed in Table 1, was conducted over 10 sessions of 1.5 hours each (one session per week) for the experimental group.

| Session | Topics | Key Content of the Structured Sessions for This Educational Program |

|---|---|---|

| First | Introduction | Introduction and providing an overview of the educational program, conducting the pre-test |

| Second | Frankl's logotherapy and its alignment with Rumi's meaning-centered teachings | Providing feedback, existential psychotherapy and the enigma of life's meaning. Perspectives on meaning in the works of Rumi and Frankl |

| Third | Meaning in Rumi's meaning-centered teachings | Providing feedback, core essence and primary intent of meaning in Rumi's thought |

| Fourth | The will to meaning as the desire and heartfelt inclination | Providing feedback, exploring the meaning of life as purpose and value |

| Fifth | Freedom and responsibility as determinism and free will, and divine decree in Rumi's meaning-centered teachings | Providing feedback determinism, free will, and divine decree |

| Sixth | Self-transcendence and existential dynamism based on Rumi's meaning-centered teachings | Providing feedback, self-transcendence or surpassing oneself based on love in Rumi's teachings, self-distancing (observing one's self) in Rumi's meaning-centered teachings, conscience or the voice of transcendence as intuitive knowledge in Rumi's philosophy |

| Seventh | Awareness and recognition of meaning as universal wisdom or absolute intellect in Rumi's meaning-centered knowledge | Providing feedback, exploring the concept of intellect and the wisdom-based approach, levels of intellect or universal wisdom |

| Eighth | Interventions and meaning-centered therapeutic tools based on Rumi's teaching | Providing feedback, the technique of de-reflection-based attitude adjustment (meaning-centered knowledge) based on Rumi's philosophy, approaches to meaning: Finding meaning in life through discovery or creation and meaning-seeking guidance based on Rumi's teachings. The paradoxical intention technique |

| Ninth | Rumi's meaning-centered understanding of human existential — death, suffering, and guilt | Providing feedback, "Patience to the Pinnacle"; Rumi and the narrative of human suffering, death or return in Rumi's thought, human fallibility and negligence in Rumi's meaning-centred teachings |

| Tenth | Meaning-centered therapy: Narrative and dialogues in meaning-centered therapy and points for reflection. Conducting the post-test | Providing feedback, reviewing assignments given throughout the therapy and practicing themr conducting meaning-centered dialogues to expand participants' value bases (practicing Frankl's "Mountain Range" exercise), asking meaning-focused questions and fostering self-transcendence, highlighting points for further reflection on the meaning of life, meaning-seeking, and meaning-finding. |

| Groups (n = 16) | Pre-test | Post-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Min-Max | Mean ± SD | Min-Max | |

| Experimental | 130.81 ± 11.12 | 108 - 150 | 182.13 ± 18.40 | 144 - 204 |

| Control | 133.25 ± 10.45 | 117 - 153 | 134.69 ± 7.85 | 117 - 144 |

| Indicator | Values | F-Statistic | P-Value | Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillai's Trace | 0.878 | 29.938 | < 0.005 | 0.878 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0.122 | - | - | - |

| Roy's Largest Root | 7.185 | - | - | - |

2.1.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 23. To assess the differences between the two groups, the ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) test was used. Conducting this analysis requires satisfying certain assumptions, which were examined before running the test. The most important assumptions include: Normality of the data distribution, homogeneity of variances, homogeneity of regression slope, and absence of outliers. The significance levels for the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests for both the control and experimental groups during the pre-test and post-test stages are higher than 0.05, and normality of data was confirmed (all P > 0.05). Furthermore, the results of Levene's Test were also not significant, indicating that the assumptions of equality of covariance matrices and equality of variances are satisfied. The fundamental assumption of experimental research and covariance analysis is the examination of the regression slope. The results indicate that this assumption is confirmed for the variable "trust in God" (the significance level in all cases is less than 0.05). With the confirmation of the assumptions, the use of ANCOVA (Analysis of Covariance) is permissible.

3. Results

According to the findings in Table 2, the mean scores for trust in God in the pre-test stage (130.81 ± 11.12) are lower than the mean scores in the post-test stage (182.13 ± 18.40) in the intervention group. However, there is no significant difference between the mean scores of the control group in the post-test and pre-test stages.

The research hypothesis was analyzed using ANCOVA. The results of the ANCOVA analysis, examining the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, are presented in Table 3.

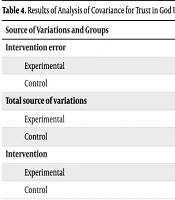

The results indicated a significant difference in the mean scores of trust in God between the pretest (130.81 ± 11.12) and posttest (182.13 ± 18.40) phases in the intervention group (F = 91.104, P < 0.05). Between-group analyses indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in the mean score of trust in God between the two groups [mean difference (95% CI): 47.440 (37.2263 to 57.6537)]. The effectiveness index also indicates that 75% of the variance in the dependent variable, trust in God, has been explained by the independent variable, the meaning-centered educational program based on Rumi's teachings (Table 4).

| Source of Variations and Groups | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Squares | F-Statistic | P-Value | Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention error | ||||||

| Experimental | 21063.781 | 1 | 21063.781 | 91.104 | ≤ 0.005 | 0.752 |

| Control | 16.531 | 1 | 16.531 | 0.194 | 0.663 | 0.006 |

| Total source of variations | ||||||

| Experimental | 6936.188 | 30 | 231.206 | |||

| Control | 2613.500 | 30 | 87.117 | |||

| Intervention | ||||||

| Experimental | 27999.969 | 31 | ||||

| Control | 2618.000 | 31 |

4. Discussion

The results indicated a significant difference in the mean scores of trust in God between the pretest (130.81 ± 11.12) and posttest (182.13 ± 18.40) phases in the intervention group (F = 91.104, P < 0.05). Therefore, it can be concluded that the intervention with a meaning-centered approach based on Rumi's teachings has had an effect on trust in God and has improved it. The results of the present study demonstrated that the research hypothesis was confirmed at a 95% confidence level. This finding aligns with the results of previous studies (11-13). Rumi believes in the authenticity and centrality of meaning in the universe, and the discussion of life's meaning is precisely intertwined with God. Rumi considers God as the essence of meaning, asserting that the truth of meaning is God Himself (9). From Rumi's perspective, meaning is synonymous with God, who is eternal and unchanging. In essence, the central theme of Rumi's philosophy is the existence of the Beloved (Divinity). Rumi repeatedly emphasizes in his works the authenticity of meaning, which is everlasting, as opposed to the illusory nature of form, a concept he highlights in "He (God) hath caused the non-existent to appear existent and magnificent; He hath caused the existent to appear in the form of non-existence". In other words, for Rumi, the world of form is the "nonexistent masquerading as existence", and the world of meaning is the "existent veiled by nonexistence." What everyone perceives are merely the forms of this material world, akin to sea foam. Rumi’s use of metaphors such as the sea and foam, wind and dust, thought and language, and sun and shadow to represent the worlds of meaning and form is profoundly illuminating and insightful.

In meaning-centered therapy based on Rumi's teachings, there is discourse about a threshold to which all of existence presents its needs. The word "Allah" is derived from the root "walah", meaning passion and yearning. Rumi adopts this interpretation and states: "In our needs, we come to You with passion, we seek them from You, and we find them in You" (16). The researcher’s model, which is a psychotherapeutic interpretation grounded in Rumi's thought, considers the Beloved (Janān) as the fundamental source of meaning (life-giving essence), playing an essential and decisive role in trust in God. This is because the connection between the soul (Jan) and the Beloved (Janān) is integral: The family of chronic mental disorders rests in God’s safe haven as they find refuge in God’s safe haven, where “no corner is free from beasts or traps” (6). By accepting the wisdom of “The clever bird, when caught in the trap, must endure” as Hafez stated (7) and relying on God and the prophetic saying: “There is no power nor strength except through God, the Exalted and Great” (17), they endure hardships and challenges with faith and trust in God. With steadfastness like a mountain, they navigate through the difficulties and sufferings associated with caregiving. In alignment with Frankl’s principle of meaning-seeking, Rumi begins the opening verses of the Masnavi (the reed flute's song) with a passionate invocation of God. By igniting the flames of yearning and desire (willpower), he sets out on a journey to seek meaning and “Indeed, we belong to Allah” (8) (Quran, Sura Al-Baqarah, Verse 156), striving to achieve the ultimate union with the Divine (6).

According to Frankl (18), de-reflection is tied to the concept of self-transcendence, where, contrary to the principle of vital equilibrium, the essence of human existence lies in transcending oneself. Self-transcendence, through love, represents the most extraordinary and unique capability of human beings. Corresponding to this idea, Rumi’s meaning-centered teachings regard love as the most pervasive phenomenon for transcendence. He discusses love as a powerful and passionate force and, at times, equates love with God. Love, by instilling the fervor of life, the sweetness of existence, valuing time, and creating a renewed perspective in the soul of the lover (19). Families of mentally ill patients, through meaning-centered therapy based on Rumi's teachings, with trust in God and focus on God and a secure attachment to the Beloved (Janān) founded on the love that invigorates and enriches their soul, are better able to overcome their stresses and discomforts. In this therapeutic process, families experienced rejuvenation and blossoming through the transformative power of love. As Rumi expresses: “The kingdom of love came and I became the eternal kingdom”. The unparalleled healing power of love is palpably felt in this approach.

Frankl (18) asserts that it is in the shadow of hardships and suffering that the meaning of life becomes evident. Meaningful suffering is purposeful suffering, aiding individuals in achieving noble goals and virtues. With this perspective, a person does not feel a sense of loss while enduring pain. Rumi employs the metaphor of the “inverted horseshoe” to describe suffering. He suggests that we often remain trapped in shadows during judgment and discernment, failing to distinguish pain from grace accurately. What we perceive as suffering may, in fact, be a form of grace, and conversely, what we recognize as blessing and pleasure might be genuine suffering. The teachings of the Masnavi emphasize that pain, like a miracle that turns copper into gold, liberates individuals from stagnation and monotony, transforming them into something greater. In Rumi's teachings, God’s decree, even when disguised as pain or hardship, is undoubtedly to the benefit of humankind. For this reason, Rumi regards suffering as a gift from God and expresses love for it. In the tales of the Masnavi, Rumi reflects on the nature of interpretation and meaning-finding in pain and suffering, their origins, and the paths to liberation from suffering: Rumi perceives true grace behind apparent hardships and recognizes genuine suffering behind superficial blessings. Inspired by the Quran, Rumi asserts in the Masnavi that existence is intertwined with inevitable suffering: “Indeed, We have created man in hardship” (8) (Quran, Sura Al-Balad, Verse 4). For Rumi, the tribulations of human life inherently carry meaning and profound concepts, emphasizing that hardships are not void of purpose but are laden with lessons and insights.

This study's findings have several theoretical and practical implications. Practically, it is recommended that psychotherapists and family interventions for patients with mental disorders consider the intervention’s foundation in the Iranian-Islamic cultural context. This study can guide researchers seeking to develop therapeutic models from indigenous and mystical sources. Future researchers are encouraged to replicate similar studies in other populations to enhance the external validity of the findings and to further investigate their efficacy in different demographic groups. The present study also has limitations; this research was conducted within a specific time frame and with a limited statistical population, which presents challenges in generalizing the findings. Additionally, a limitation of this study was the lack of matching between the two research groups in terms of gender, education level, and socioeconomic status.

4.1. Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study, we conclude that the meaning-centered educational program based on Rumi's teachings is an effective intervention for enhancing levels of trust in God among families of chronically mentally ill patients. In Rumi's Masnavi Ma’navi, an influential mystical work, there are profound theoretical and philosophical aspects that can independently serve as the foundation for a form of indigenous psychotherapy. In explaining this result, it can be argued that families of mentally ill patients, having lived for centuries within the framework of Iranian-Islamic culture and civilization, are receptive to and understand the metaphors and analogies in Rumi's thought.