1. Background

Pregnancy is associated with complex physiological and psychological changes that affect the couple's life, including their sexual and marital relationships, which can either deepen the couple's relationship or lead to separation. The quality of sexual life is a subjective concept based on an individual's understanding of the sexual aspect of their life, representing a dynamic interaction that evolves over time and according to circumstances. It serves as a means to explore the relationship between sexual problems and quality of life (1-6). The quality of sexual life changes during pregnancy, often decreasing with increasing gestational age. Additionally, factors such as the woman's age, education level, and whether the pregnancy is desired impact the quality of sexual life in pregnant women. Sexual behavior during pregnancy and postpartum can be influenced by biological factors (fatigue, dyspareunia, and back pain), psychological factors (depressed mood, negativity, and guilt), interpersonal factors (decreased sexual interest, unwanted pregnancy, dissatisfaction with interpersonal relationships), and fears and worries (such as fear of harm to the fetus, pain, premature birth, miscarriage, and bleeding during intercourse). According to Johnson's study, maintaining mutual sexual relations during and after pregnancy promotes physical health, well-being, and increased intimacy (2, 7-9).

Sex counseling is a form of talk therapy designed to assist individuals whose physical, psychological, personality, or communication issues affect their sexual satisfaction. It is a type of psychological counseling that helps individuals fully enjoy sexual relations with their partner. Sexual counseling improves the quality of sexual life by enhancing marital relations. During pregnancy, sexual counseling can lead to better emotional and physical adaptation for the couple, increase their sexual awareness, and ultimately improve the quality of their sexual life and compatibility (10-13).

The BETTER sexual counseling model, introduced in 2004 by Mick and colleagues, offers a structured approach to addressing sexual issues in an oncology center (10). It is now used in various clinical settings. A study in Iran demonstrated that the BETTER model significantly enhances women's sexual health compared to other models (14). Similarly, a study in Egypt found the BETTER model to be highly effective in improving women's sexual health (9). Various sexual counseling frameworks, such as ALARM, PLISSIT, Sexual Health Model, and PLEASURE, have been evaluated to address infertility-related negative consequences and promote sexual function (15). However, no definitive information suggests which model is most effective in improving sexual function across all domains (16).

The BETTER model provides a framework for discussing sexual issues arising from medical conditions. It consists of six steps that enhance health practitioners' knowledge and skills, facilitating a communicative process that reduces anxiety and stress while increasing sexual satisfaction (2, 10). Unlike other models, this sexual counseling approach offers an opportunity to listen, assess, and guide women in just two sessions, making it ideal for the cultural context of Iran. Sexual self-disclosure and the removal of barriers to sexual communication between couples can improve the quality of sexual life and satisfaction (11, 17-19). By offering advice on sexual issues, mothers can be better prepared to adapt to changes during pregnancy (20, 21).

2. Objectives

This study was conducted considering the importance of the quality of sexual life and its interrelationship with the general quality of life. Since the application of BETTER model in sexual counseling during pregnancy was less considered in Iranian population, this study aimed to investigate the effect of sexual counseling based on the BETTER model on the quality of women’s sexual life during pregnancy.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was conducted as a parallel randomized clinical trial involving 128 pregnant women (64 in the intervention group and 64 in the control group) with gestational ages ranging from 14 to 25 weeks. These participants were recruited from health centers in Bahmai County, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, Iran, in 2021.

3.2. Study Sample

The required sample size was estimated to be 64 participants, considering a type 1 error of 0.05, 80% power, 30% attrition, and the mean and standard deviation in the intervention group (μ1 = 9.8, σ1 = 3) and in the control group (μ2 = 11.6, σ2 = 2.9). To account for potential dropouts, a total of 144 participants were selected and randomly assigned to the control and intervention groups using simple randomization (Excel was used to generate a table of random numbers).

Inclusion criteria included primiparous pregnant women aged 18 - 35, gestational age of 15 - 25 weeks, literacy in reading and writing, singleton pregnancy, and consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were the use of drugs or alcohol, high-risk pregnancy factors, chronic and mental diseases before and during pregnancy, history of miscarriage or infant death, use of drugs affecting sexual response, marital disputes, separation from the spouse during the study, and pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

Data were collected using a demographic questionnaire (including mother's age, spouse's age, father's occupation, mother's occupation, mother's education, spouse's education, income status, week of pregnancy, place of residence, illness, and medication use, time of marriage) and the quality-of-life questionnaire. The latter was initially designed in 1998 and revised and validated in 2005 by Symond and colleagues (22). This questionnaire was translated into Farsi and psychometrically evaluated by Masoumi et al. using qualitative and quantitative methods (CVR = 0.84, CVI = 0.91). The reliability coefficient of this tool was assessed using Cronbach's alpha method, with a standardized value of 0.73. The questionnaire consists of 18 questions with a six-point Likert scale (23). The minimum score is 18, and the maximum score is 108, with higher scores indicating a more favorable level of sexual life quality. Scores up to 36 are considered weak, scores from 37 - 72 are classified as middle class, and scores from 73 - 108 are considered good (24).

Participants in both groups (intervention and control) completed the demographic questionnaire and the sexual life quality questionnaire. The completion of the questionnaires was monitored at three stages: (1) Before the intervention, (2) after the intervention, and (3) during the follow-up stage one month later by a trained midwife who was unaware of the group assignments and capable of addressing any questions from the participants. Proper nutrition, transportation, and free midwifery visits for pregnant women were provided by the researcher.

3.4. Interventions

The intervention consisted of two 45 - 60-minute group counseling sessions (two counseling sessions were held for each group, each group had 32 people, in fact, a total of 4 counseling sessions were held) using the BETTER sexual counseling model, conducted by a master's student specializing in midwifery counseling (Table 1). In the first session, the model was introduced, and in the second session, the intervention was applied. The student's skill was confirmed by the supervisor. After group assignment, mothers in the intervention group were invited for the first counseling session, with the second meeting scheduled 2 - 4 weeks later, based on the mother's condition and agreement. The control group received only routine pregnancy care. The sex life quality questionnaire was completed immediately after the counseling and one month later for both groups. The time interval for completing the questionnaires was consistent for both groups. After the study, group sex counseling was provided for the control group. The primary outcome assessed was women’s sexual life quality.

| Stage | Purpose | Content |

|---|---|---|

| B: Bring up | Finding a way to start a conversation about sexual problems/understanding the client's sexual problems | The counselor simply talks about sex with the client, asking about intimacy and relationships with her spouse, and tells she can talk about it quite comfortably. This step is intended to create an opportunity for the client to talk about sex and identify her concerns. If the client decides not to talk about it, she informs the counselor at this stage. |

| E: Explain | Helping to normalize sexual discourse and reduce the client's sense of shame | At this stage, the counselor explains to the mother that sex is an important and necessary aspect of life and that it affects various aspects of marital life and quality of life. The counselor encourages the client to talk more about sexual problems with her husband and also tells the client that she is completely free to talk about this matter. |

| T: Tell | Continuation of the conversation to reassure the client to solve the individual's sexual problem/gain the client's trust/give basic information | The counselor assures the client that he will provide all the information he she needs to solve her problem, and the client can request information in any case. The counselor is also ready to answer and, if necessary, will refer the client to the relevant specialist to solve the problem. |

| T: Timing | Determining the right time for consultation according to the client's preference | The time of the consultation is determined based on the client's preference. If she wishes, the issues are addressed in the same session or a time is set for it. In some studies, the model is implemented over two sessions so that the client is prepared to talk about sexual problems and the timing is according to the client's preference. The client can request the necessary information in the future |

| E: Educate | Training the client according to the stated problem/giving the information needed by the person | At this stage, the client is given the necessary training according to her problems, for example, about fear of intercourse, pain during intercourse, sexual superstitions. and the effects of pregnancy on sexual issues. At this stage, the counselor can use audio and video resources for better education. The counselor can also teach the client useful exercises. |

| R: Record | Recording medical evaluations and interventions for further follow-up | Assessments, interventions, and treatment outcomes are recorded confidentially so that the client can be accessed in subsequent sessions if necessary. Integrating information can help improve the quality of the counseling process and improve outcomes. |

BETTER Sexual Counseling Model

3.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive (frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation) and inferential (chi-square, t-test, ANOVA, and repeated measures) statistics with SPSS 18. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

All participants signed a written informed consent before participation. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (IR.SHMU.REC.1399.043) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) under the number IRCT20200516047467N1 during the period of July to December 2019.

4. Results

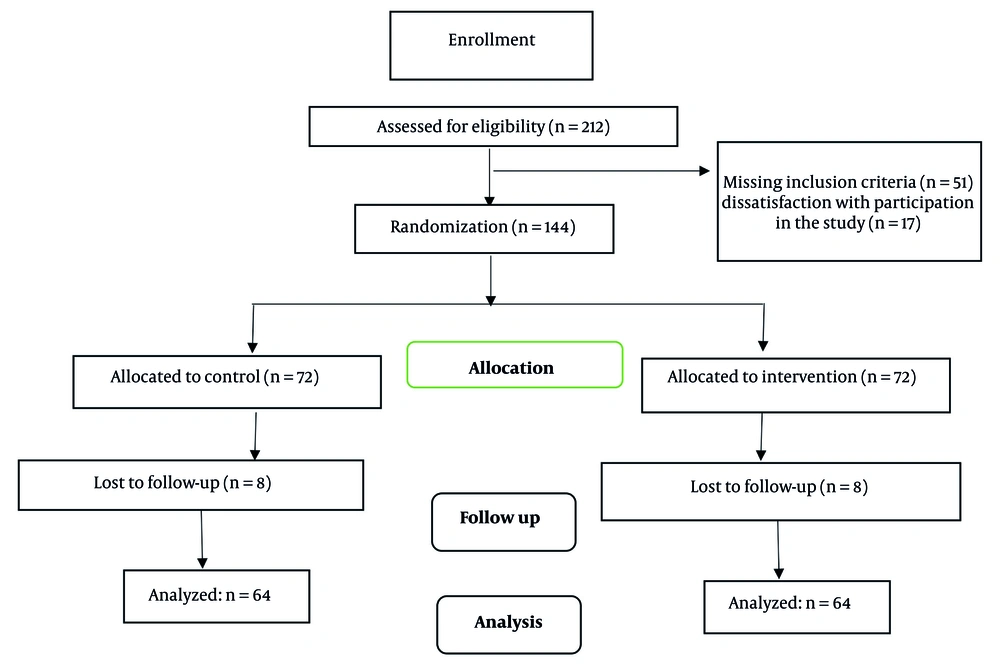

In this study, a total of 132 participants (64 in the intervention group and 64 in the control group) were involved (Figure 1). The demographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table 2. Except for income status, there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups regarding the average age of the mother, week of pregnancy, length of marriage, education of the participants and their spouses, and occupation of the participants and their spouses.

| Variables | Consultation Group | Control Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's age (y) | 27.61 ± 4.51 | 27.05 ± 4.75 | 0.493 |

| Spouse's age (y) | 31.88 ± 5 | 31.22 ± 6.23 | 0.512 |

| Duration of marriage (y) | 2.56 ± 0.957 | 2.50 ± 0.873 | 0.700 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 19.66 ± 3.04 | 19.39 ± 2.97 | 0.618 |

| Mother's education | 0.341 | ||

| Elementary school | 4 (6.25) | 6 (9.37) | |

| Middle school level | 18 (28.12) | 10 (15.62) | |

| Diploma | 25 (39.06) | 26 (40.64) | |

| University | 17 (26.56) | 22 (34.37) | |

| Husband's education | 0.420 | ||

| Elementary school | 2 (3.12) | 4 (6.25) | |

| Middle school level | 15 (23.48) | 9 (14.06) | |

| Diploma | 33 (51.56) | 39 (60.93) | |

| University | 14 (51.56) | 12 (18.75) | |

| Mother's job | 0.243 | ||

| Employee | 10 (15.62) | 14 (21.87) | |

| Self-employee | 26 (40.61) | 29 (45.32) | |

| Housewife | 28 (75.43) | 21 (32.81) | |

| Husband's job | 0.817 | ||

| Employee | 13 (20.31) | 16 (25) | |

| Freelance job | 50 (78.12) | 47 (73.43) | |

| Manual worker | 1 (1.56) | 1 (56.1) | |

| Income status | 0.031 | ||

| Enough | 14 (21.9) | 21 (32.8) | |

| Relatively enough | 32 (50) | 35 (54.7) | |

| Insufficient | 18 (28.1) | 8 (12.5) | |

| State of residence | 0.633 | ||

| Rental | 8 (12.5) | 9 (14.1) | |

| Personal | 42 (65.6) | 44 (68.8) | |

| Parents' house | 14 (21.9) | 11 (17.2) | |

| Illness and drug use | 0.759 | ||

| Yes | 8 (12.7) | 7 (10.9) | |

| No | 56 (87.3) | 57 (89.1) |

. Demographic Variables in Two Consultation and Control Groups

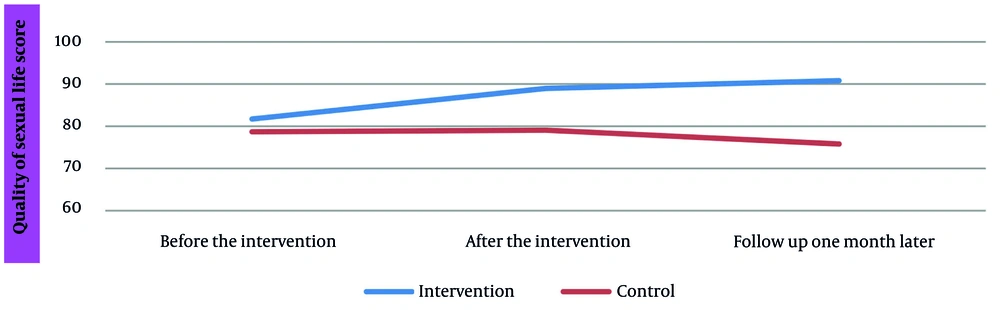

There was no significant difference in the quality of sexual life scores between the two groups before the intervention. However, immediately after the intervention and one month later, the intervention group exhibited significantly higher scores, indicating improvement in these variables. Given that three time points were assessed in this study, a repeated measures analysis was conducted. Sphericity was examined, and due to the rejection of the sphericity hypothesis, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to evaluate the effect of time, the interactive effect of time-group, and the effect of group, all of which were significant (Table 3).

| Variable and Time | Consultation Group | Control Group | P-Value | Source | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women’s sexual life | ||||||

| Before intervention | 81.70 ± 17.93 | 78.75 ± 0.343 | 0.343 | Time | 17.20 | 0.001 |

| After the intervention | 88.98 ± 15.01 | 77.62 ± 17.12 | 0.002 | Time*group | 63.36 | 0.001 |

| One month after intervention | 90.81 ± 14.15 | 75.08 ± 16.65 | 0.001 | Group | 42.55 | 0.001 |

Mean Scores of Women’s Sexual Life During Pregnancy in the Consultation and Control Group

Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, with the significance of the effect of time and based on pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni adjustment, it was found that the mean scores of women’s sexual life changed from one time point to the next, regardless of the intervention and control groups. The significance of the interaction effect of the group over time indicates that changes in the quality-of-life scores over time were significantly different between the two groups. Additionally, time was significant regardless of the group, meaning that even without the intervention, time alone would alter the average quality of sexual life.

Moreover, the average quality of sexual life in the intervention group increased from the pre-intervention phase to immediately after the intervention and continued to improve one month later. In contrast, this trend decreased in the control group (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

Studies have shown that pregnancy is one of the most sensitive periods in a woman's life, characterized by numerous physical and psychological changes affecting sexual intercourse (25). According to the results of the present study, the BETTER model sexual counseling intervention positively impacted the quality of pregnant mothers’ sexual life, with this effect persisting until the follow-up stage one month later. A study conducted in England found that the mental evaluation of sexual life depends on marital relationships, emotional expression, and intellectual coherence. However, there was no correlation between sexual activity and the quality of sexual life with the evaluation of the marital relationship quality. Nevertheless, the evaluation of sex life is significantly related to the evaluation of marital quality (26), which aligns with our study on the relationship between sexual activity and the quality of sexual life.

A study conducted in Spain titled "The Impact of Pregnancy on Women's Sexual Life" showed that changes in sexual behavior during pregnancy should not be considered abnormal or pathological (27). This finding underscores the need to manage sexual changes caused by pregnancy, such as the intervention conducted in the present study. In 2015, a study in Iran with 80 pregnant women from 13 to 33 weeks showed that participating in four sex counseling sessions of 45 to 90 minutes during pregnancy improved the quality of sexual life. These results were maintained in the follow-up two weeks after the study ended, but no significant difference was observed between before the intervention and four weeks later. This research used the 45-question Enrich 1 questionnaire to investigate the effect of counseling sessions (23). The findings of this study differed from our results, possibly due to the use of different scales or counseling models.

Additionally, another study in Iran showed that sexual counseling sessions during pregnancy every three months positively affect the quality of sexual life for pregnant women. This study used the SQOL-F questionnaire to assess sexual life quality. The results revealed that the quality of sexual life decreases significantly as pregnancy progresses, and sexual counseling sessions effectively address this issue (28). Furthermore, another Iranian study using the Pregnancy Sexual Response Inventory (PSRI) indicated a positive effect of participating in five sexual counseling sessions during pregnancy on the quality of sexual life six weeks after the intervention (29). Similar to the present study, research on the effect of sexual counseling based on the PLISSIT model on the sexual functioning of pregnant women in Iran showed significant improvement in sexual life two and four weeks after counseling (30).

In Turkey, a study similar to the present one examined the effect of participating in two sexual counseling sessions based on the BETTER model on the quality of sexual life for 35 pregnant women using the FSFI. The results demonstrated that participating in two sexual counseling sessions based on the BETTER model improves the quality of sexual life during pregnancy (2). All these studies are consistent with our findings, highlighting the impact of interventions (counseling, programs, classes, etc.) on sexual quality during pregnancy. Health care providers should be more aware of the impact of sexual performance on a woman's life and address sexual problems comprehensively in daily practice. The BETTER model, being client-centered and emphasizing the formation of an acceptable atmosphere between client and counselor, allows women to disclose their sexual issues more effectively, potentially altering the treatment process, especially during pregnancy.

There are some limitations in this study. While individuals diagnosed with severe psychological diseases were excluded due to the role of psychological variables in women's sexual function, the psychological health of participants was not compared, which is a limitation. Therefore, due to the narrow demographic variations in the sample, the generalizability of these findings should be approached with caution.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of the present study indicate the effectiveness of the sexual counseling method based on the BETTER model in improving the quality of sexual life during pregnancy. Today, one of the most important features of health care and midwifery is addressing sexual problems without using drugs, employing simple and low-risk methods. Providing sexual counseling is simple, inexpensive, and accessible, and it can prepare mothers for the changes during pregnancy and help them adapt.