1. Introduction

Granulomatous orchitis is an inflammatory change of the testis. it is a rare lesion with specific and nonspecific etiology. Brucellar epididymo-orchitis is an uncommon cause of the testis and epididymis infections. It occurs in around 5-10% of all brucellosis (1). The clinical appearances of granulomatous orchitis varies, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish from testicular cancer. The diagnosis is usually made based on the histological examination only after orchiectomy (2). The present study reports one case of specific granulomatous orchitis due to brucellosis in an 18-year-old patient. A review of the literature is made on the pathogenesis and diagnosis.

2. Case Presentation

An 18-year-old male complained of right lumbago and pain in both knees, since one and a half months before admission. The pain was resolved several days after consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), while no antibiotic was taken; after that, the subject had no symptom for almost one month. He consulted the infectious clinic while complaining of fever and severe pain and swelling in left testis over the last four days. He had a history of unpasteurized ice cream consumption, but no history of urinary tract infection, sexual contact, genitalia trauma, surgery or urinary catheterization and had completed his vaccination series. He did not have dysuria, frequency, cloudy urine, urethral discharge, or blood in the semen. After the examination, the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and abdomen were found normal. There was no swelling in parotid glands and inguinal adenopathy. The scrotal skin was erythematous, warm and was freely moving on testis. Left testis was enlarged, hard, and tender. Rectal exam was normal. He was admitted to the hospital for the treatment of epididymo-orchitis and also ruling out the brucellosis. Empirical antibiotic therapy was instituted; initially he received IV fluoroquinolone. To provide symptomatic relief, analgesics, scrotal elevation and ice pack were advised. After a few days, there was no clinical response, therefore meropenem was added to ciprofloxacin. After almost one week of antibiotic therapy, the sign and symptoms of testis and scrotum infection just slightly changed. In addition, the musculoskeletal pain relapsed, thus empirical therapy with doxycycline and rifampin was started and a few days later, the signs and symptoms significantly decreased.

2.1. Paraclinical Results

WBC: 11700 per µL (Neut: 78%), Hb: 13.4 g/dL, plt: 184000 per µL, CRP: 96, ESR: 23, BUN: 38 mg/dL, Cr: 1 mg/dL, VDRL: negative, αfp: 1.7 (< 5.8) ng/mL, BHCG: < 1 (up to 2.6) mIU/mL, LDH: 223 (250-500) IU/L, Wright: 1/40, Combs-Wright: 1/80, 2ME: 1/40, anti-Brucella ELISA: positive; PPD: negative; U/A: normal; culture of urine, blood and needle scrotal drainage were negative; chest X-ray, abdominal and pelvic sonography, and also sacroiliac CT-scan were normal.

Ultrasonography of urinary system: kidneys, bladder, ureters, urethra and right testis were normal. Left testis was 61 × 26 mm which was bigger than normal size. Echogenicity of left testis was heterogeneous. In addition, one hypoechoic mass (8.5 × 4.5 × 9.5 mm) with ill-defined border was observed which probably recommended early stage of abscess formation. Other findings were also reported including slight thickness in left scrotum, the large size of the left epididymis containing one ill-defined hypoechoic area, and mild hydrocele with septation around the left testis.

Scrotal scan: after IV injection of Tc99m-pertechnetate, scanning was performed in the anterior projection, the scan revealed no significant abnormal radiotracer activity in both sides; no clear evidence of pathology of scrotum was detected.

Based on these findings and the clinical response to anti-brucellosis treatment, the patient was discharged with doxycycline and rifampin. During the follow-up, after almost one month, the pain and swelling of the left testis completely disappeared, but in its examination, a small nodule was detected.

The second ultrasonographic findings revealed: right testis measured 42 × 19 mm with normal echo pattern, the left side one, measured 46 × 25 mm and heterogeneous hypoechoic and hypervascular mass like lesion was observed at its upper pole about 18 × 15 mm, suggestive of neoplastic pathology. In addition, the left side epididymal structures were engorged and thickened. No hydrocele was detected and also grade I varicocele was observed at left side. No obvious para-aortic adenopathy was defined. Arterial flow pattern at both testes as well as other parts were normal.

The patient was referred to an urologist and underwent a surgery. In operation room, based on frozen section technique, highly suggestive of malignant lesion was reported. Therefore left sided radical orchiectomy was immediately performed. The diagnosis was made after orchiectomy.

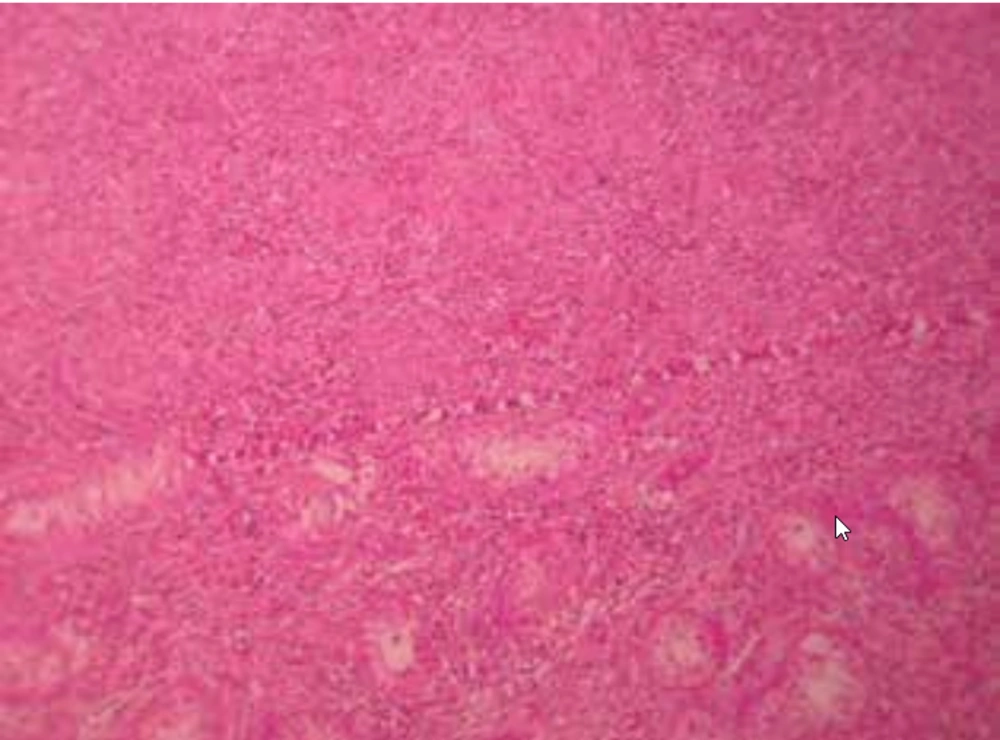

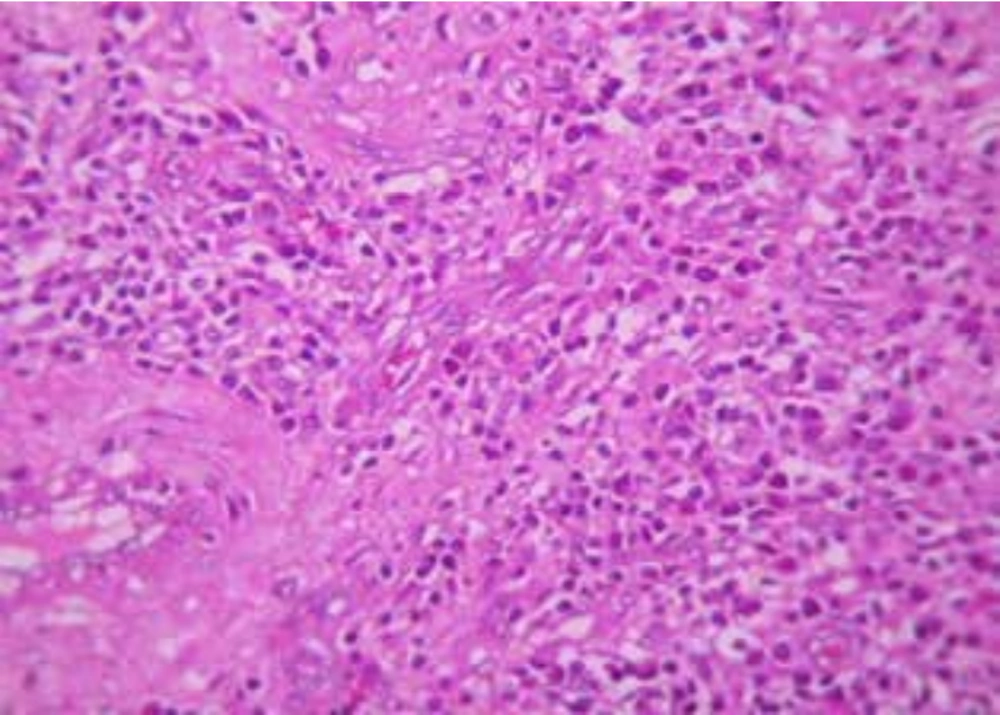

On gross examination of the pathology sample, one solid nodular soft gray-tan mass, measuring 3 cm was observed in the central portion of testis. The microscopic examination included the seminiferous tubules and interstitium that were infiltrated by granulomas of non-necrotizing type, rich in plasma cells. The epididym, showed chronic nonspecific inflammation (Figures 1 and 2).

After surgery he completed the medical therapy for brucellosis, and in the follow up periodic visit during two years, he had no complaints, abnormal physical or paraclinical findings (including WBC, ESR, CRP and ultrasonography).

3. Discussion

Epididymo-orchitis is the most frequent genitourinary complication of brucellosis, and should be considered as the differential diagnosis of any scrotal diseases in endemic areas.

The most common reported symptoms are scrotal pain (94%) and swollen testis (82%). A conservative approach is usually adequate to manage brucellar epididymo-orchitis. However, infertility problems may develop in some patients (3).

For the first time, granulomatous orchitis was described by Grunberg in 1926. The condition tends to manifest unilaterally in males aged 19 - 84 years. Granulomatous orchitis may be caused by specific or idiopathic origin (4). Specific granulomatous orchitis is subdivided into two major types: A) non-infectious granulomatous orchitis (such as sarcoidosis); and B) infectious granulomatous orchitis (5). Tuberculosis is the most common specific cause, followed by brucellosis, syphilis, actinomycosis, leprosy, and some fungal infections (6). Granulomatous orchitis has been also reported as a complication following the intravesical administration of BCG in the treatment of bladder tumors (7).

Idiopathic granulomatous orchitis is a chronic inflammation of the testis parenchyma, whereas the etiology is not clear, possible causes are firstly prior testis trauma and secondly a sperm immune reaction. The role of infection in the etiology of idiopathic granulomatous orchitis must be also taken into account. In such circumstances, urinary tract bacterial infection has been observed in patients with granulomatous orchitis (in up to 30% of cases in some series) although direct demonstration of bacterial implication has not been possible.

Patients with granulomatous orchitis may experience long-lasting mild or no discomfort, accompanied by swollen testis, and some cases are characterized by acute scrotal pain (4). The most common reported symptoms are scrotal pain (94%) and swellen testis (82%) (3). Physical examination of the affected testis is normally unable to differentiate between a testicular tumor and possible granulomatous orchitis.

Ultrasound, which is so useful in the application of scrotal pathology, is often used to establish the differential diagnosis with malignant tumors. However, in granulomatous orchitis, the testis tends to be diffusely hypoechoic, with poorly or well defined focal intra-testicular zones (4).

Orchiectomy is the main form of treatment, because antibiotics, and anti-inflammatory drugs have slight effect on the disease; moreover, at the time of diagnosis, the testis is already damaged (8).

Histologically, in brucellosis, intratubular and interstitial types were identified as complete testicular destruction (9). Necrotizing orchitis is a rare form of Brucella infection that must be distinguished from infection caused by other pathogens (Tuberculosis or Salmonella) (10).

Granulomatous orchitis clinically may resemble epididymo-orchitis or malignancy. Seminoma and granulomatous orchitis occur in the same age groups with similar clinical presentations. As testicular biopsy is contraindicated in a suspected case of malignancy, the diagnosis of granulomatous orchitis can be achieved only on histopathology of resected testis (11). No relationship was found between granulomatous orchitis and testicular carcinoma, and no reports were found in the literature of granulomatous orchitis presenting with or after testicular neoplastic lesions (4).

In the present case report, Wright, Combs-Wright and 2-ME tests were not highly positive in several repeated tests and the cause of these unclear results were not known. However, brucellar granulomatous orchitis was diagnosed based on the clinical symptoms (fever and musculoskeletal pain which disappeared after anti-Brucella treatment), epidemiological history (consumption of unpasteurized ice cream) and paraclinical findings (positive anti-Brucella ELISA, and pathological reports including noncaseating granuloma with infiltration of predominantly plasma cells).