Abstract

Background:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is considered the leading cause of liver disease worldwide. Although many previous studies have evaluated the potential risk factors of NAFLD, few studies have determined the effect of residency or marriage status on NAFLD.Objectives:

We aim to evaluate whether residency and marriage status increased the risk factors for NAFLD.Materials and Methods:

We utilized data from 5,052 participants, 18 years and older, from a cohort study conducted using 6,140 participants in northern Iran. The population was divided into 16 subgroups according to sex and age; the age groups had an interval of 10 years. We randomly selected the subjects from each subgroup in proportion to the size of each subpopulation group. Logistic regression analyses were conducted on NAFLD as an outcome of marriage status, residency (rural vs. urban), and other potential risk factors.Results:

We found that NAFLD had an inverse association with rural living in men (OR = 0.513, 0.422 - 0.622, P value < 0.001) and women (OR = 0.431, 0.345 - 0.539, P value < 0.001). Furthermore, we determined that NAFLD had a direct association with marriage status for men (OR = 2.770, 2.004 - 3.831, P value < 0.001) and women (OR = 1.241, 1.033 - 1.490, P value = 0.0209).Conclusions:

While rural living has a protective effect on NAFLD, marriage may be a potential risk factor for this condition.Keywords

1. Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is considered the leading cause of liver disease worldwide (1). NAFLD is comprised of a wide spectrum of liver pathologies, from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFLD can lead to liver cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2). The prevalence of this condition has been estimated to be 20% - 30% in western countries, and there is an increasing trend in low- and middle-income countries (1, 3). The increasing prevalence of NAFLD is attributable to the increasing incidence of obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome (MetS), and other metabolic conditions (4, 5). Studies have been conducted to determine the prevalence and associated risk factors of NAFLD. Based on these studies, an association was established between NAFLD and age, obesity, blood pressure (BP), dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance (6, 7). However, to the knowledge of the authors, only a few studies have evaluated the effect of residency and marriage status on NAFLD.

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted to evaluate the risk factors of NAFLD associated with residency and marriage.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Population

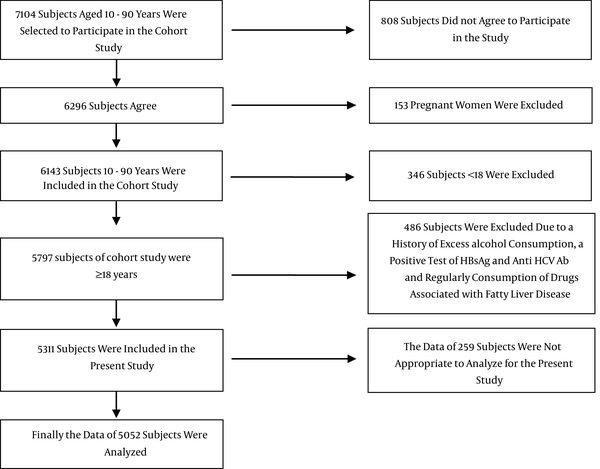

In the present study, we used data from 5,052 participants, who were 18 years and older, who were part of a cohort study of 6,140 participants in Amol, which is a populated city in Northern Iran. The cohort study involved individuals who were between the ages of 10 - 90 years. The primary health care settings provided the sampling frame since each citizen had a health record. The participants were divided into 16 subgroups according to sex and age; each age group had an interval of 10 years. We randomly selected the subjects from each subgroup in proportion to the size of each subpopulation group. More details of the sampling strategy used in our cohort study were provided in our previous study (8). Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of how the study population was chosen.

A Schematic Diagram of the Study Participants and Exclusions

3.2. Data Collection

Trained healthcare providers measured the weight, height, waist circumference (WC), hip circumference (HC), and blood pressure (BP) of each participant. Weight and height measurements were taken once the participants had removed excess clothes and shoes. Height was measured when the participant was in an upright position, with the heels and buttocks in contact with the wall. WC was determined at the midpoint of the distance between the lowest costal ridge and the upper border of the iliac crest. The largest circumference between the waist and knee was measured for the HC. Following at least 5 min of rest, the BP was measured using a fitted cuff while the participant was in a sitting position. Both the diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and the systolic blood pressure (SBP) were recorded.

After 12 hours of fasting, levels of fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profiles were evaluated for each participant. All laboratory tests, including FBS and lipid profiles, were assessed enzymatically based on a protocol using an automatic BS-200 analyzer (Mindray, China).

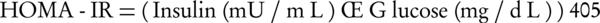

NAFLD was determined using evidence of hepatic steatosis shown in a sonogram where there was a lack of evidence of other causes of acute or chronic hepatitis, such as significant alcohol consumption, use of steatogenic medication, or hereditary disorders. A single radiologist carried out all ultrasound examinations. Using the ultrasound method to detect NAFLD has some limitations since it is operator and machine dependent; it is also limited in its use to detect steatosis in obese patients and in those patients with an excess of gas in the intestine (9). The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated according to the following equation (Equation 1):

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The logistic regression analyses were conducted separately for men and women for NAFLD as an outcome. The potential predictors that were used in the analyses were: age, marriage (married vs. unmarried), residency (rural vs. urban), smoking (smoking vs. non-smoking), obesity (obese vs. non-obese), blood pressure (high BP vs. low), triglyceride (high TG vs. low), and high-density lipoprotein (low HDL vs. high). The obesity, high BP, high TG, and low HDL were defined based on a joint interim statement definition of MetS (10). The Wald test, significant levels, and odd ratios (OR) were reported. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed for the logistic regressions. All statistical analyses were conducted using statistical software (SPSS Inc., version 21, Chicago, IL and Stata software, version 12, StataCorp, Texas, US). The significant levels in all analyses were considered to be 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the study population based on residency. While the rural people had a higher WC, SBP, AST, FBS, HDL, and HOMA, the urban people had a higher DBP.

| Residency | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Urban (n = 2611) | Rural (n = 2441) | |

| Age | 44.26 ± 16.0 | 44.25 ± 16.43 | 0.674 |

| WC | 90.50 ± 13.12 | 91.76 ± 12.42 | 0.0002 |

| DBP | 78.07 ± 12.68 | 74.34 ± 12.76 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP | 116.07 ± 16.31 | 117.07 ± 16.92 | 0.0211 |

| GGT | 27.93 ± 20.10 | 28.28 ± 29.03 | 0.6609 |

| ALT | 23.31 ± 16.22 | 23.66 ± 18.55 | 0.4404 |

| AST | 21.73 ± 11.98 | 22.80 ± 11.24 | 0.0005 |

| FBS | 99.99 ± 35.66 | 101.96 ± 35.05 | 0.0348 |

| TG | 141.28 ± 96.71 | 146.13 ± 97.86 | 0.0668 |

| HDL | 43.66 ± 11.40 | 45.72 ± 12.17 | < 0.0001 |

| HOMA | 2.05 ± 2.06 | 2.81 ± 2.22 | < 0.0001 |

| Prevalence and Percent | |||

| NAFLD | |||

| Men | 43.06 (40.58 - 45.54) | 37.50 (35.23 - 39.77) | 0.0012 |

| Women | 47.68 (45.12 - 50.24) | 39.31 (36.35 - 42.27) | < 0.0001 |

| Unmarried people | 20.07 (18.63 - 21.50) | 15.82 (14.47 - 17.17) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking | 12.70 (11.50 - 13.90) | 16.40 (15.03 - 17.77) | 0.0001 |

Table 2 shows the basic characteristics of the study population based on marriage status. Based on our results, married people had a higher mean age, WC, DBP, GGT, ALT, FBS, and TG, but a lower HDL than unmarried people did.

| Marriage Status | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Unmarried (n = 910) | Married (n = 4142) | |

| Age | 29.38 ± 16.00 | 47.62 ± 14.28 | < 0.0001 |

| WC | 83.24 ± 13.59 | 92.836 ± 11.95 | < 0.0001 |

| DBP | 75.01 ± 13.43 | 77.58± 13.81 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP | 111.91 ± 15.61 | 115.25 ± 16.86 | < 0.0001 |

| GGT | 22.73 ± 13.74 | 29.30 ± 27.86 | < 0.0001 |

| ALT | 21.97 ± 17.01 | 23.81 ± 17.46 | 0.0019 |

| AST | 22.06 ± 11.06 | 22.29 ± 11.77 | 0.5637 |

| FBS | 93.68 ± 25.42 | 102.55 | < 0.0001 |

| TG | 115.23 ± 64.31 | 149.44 ± 101.79 | < 0.0001 |

| HDL | 45.90 ± 11.43 | 44.41 ± 11.91 | 0.0003 |

| HOMA | 2.38 ± 1.99 | 2.43 ± 2.21 | 0.4875 |

| Prevalence and Percent | |||

| NAFLD | |||

| Men | 15.58 (12.75 - 18.41) | 45.88 (43.98 - 47.78) | < 0.0001 |

| Women | 25.84 (21.63 - 30.06) | 47.83 (45.69 - 49.96) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking | 5.76 (4.34 - 7.17) | 16.40 (15.34 - 17.45) | < 0.0001 |

Table 3 shows the results of the univariate and multivariate binary logistic regressions. In these analyses, the NAFLD was considered to be the outcome variable. NAFLD had a direct association with marriage status in men (OR = 2.770 (2.004 - 3.831), P value < 0.001) and women (OR = 1.241 (1.033 - 1.490), P value = 0.0209), and an inverse association with living in rural areas for men (OR = 0.513 (0.422 - 0.622), P value < 0.001) and women (OR = 0.431 (0.345 - 0.539), P value < 0.001).

The Results of Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses

| Methods | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Predictors | Wald | OR (CI) | P Value | Wald | OR (CI) | P Value |

| Men (n = 1659) | ||||||

| Age | 110.69 | 1.023 (1.019 - 1.028) | < 0.0001 | 1.97 | 1.005 (0.998 - 1.012) | 0.1599 |

| Marriage (married vs. unmarried) | 162.428 | 4.273 (3.425 - 5.347) | < 0.0001 | 37.943 | 2.770 (2.004 - 3.831) | < 0.0001 |

| Residency (rural vs. urban) | 10.50 | 0.793 (0.690 - 0.913) | 0.0012 | 45.47 | 0.513 (0.422 - 0.622) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoker vs. non-smoker | 1.87 | 0.893 (0.759 - 1.050) | 0.1711 | 4.07 | 0.805 (0.652 - 0.994) | 0.0437 |

| WC (obese vs. non-obese) | 766.20 | 13.912 (11.546 - 16.763) | < 0.0001 | 363.34 | 7.859 (6.358 - 9.715) | < 0.0001 |

| BP (high vs. low) | 138.23 | 2.451 (2.111 - 2.847) | < 0.0001 | 5.25 | 1.257 (1.034 - 1.528) | 0.0219 |

| TG (high vs. low) | 209.93 | 3.139 (2.689 - 3.665) | < 0.0001 | 18.96 | 1.580 (1.286 - 1.942) | < 0.0001 |

| HDL (low vs. high) | 133.04 | 2.362 (2.041 - 2.734) | < 0.0001 | 2.40 | 1.169 (0.959 - 1.423) | 0.1215 |

| HOMA | 249.88 | 1.537 (1.457 - 1.621) | <0.0001 | 91.33 | 1.383 (1.294 - 1.478) | < 0.0001 |

| Women (n = 1314) | ||||||

| Age | 353.44 | 1.061 (1.055 - 1.068) | <0.0001 | 88.50 | 1.038 (1.030 - 1.047) | < 0.0001 |

| Marriage (married vs. unmarried) | 15.69 | 1.346 (1.161 - 1.558) | < 0.0001 | 5.33 | 1.241 (1.033 - 1.490) | 0.0209 |

| Residency (rural vs. urban) | 17.30 | 0.711 (0.605 - 0.835) | < 0.0001 | 54.26 | 0.431 (0.345 - 0.539) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoker vs. non-smoker | 0.22 | 1.264 (0.473 - 3.378) | 0.6407 | 0.15 | 0.756 (0.188 - 3.063) | < 0.0001 |

| WC (obese vs. non-obese) | 567.84 | 11.802 (9.634 - 14.458) | < 0.0001 | 229.40 | 6.233 (4.919 - 7.899) | < 0.0001 |

| BP (high vs. low) | 151.06 | 3.009 (2.524 - 3.587) | < 0.0001 | 4.69 | 1.288 (1.024 - 1.619) | 0.0303 |

| TG (high vs. low) | 220.66 | 4.034 (3.356 - 4.848) | < 0.0001 | 31.95 | 1.954 (1.549 - 2.464) | < 0.0001 |

| HDL (low vs. high) | 98.10 | 2.407 (2.023 - 2.864) | < 0.0001 | 3.67 | 1.253 (0.995 - 1.577) | 0.0553 |

| HOMA | 161.23 | 1.301 (1.242 - 1.363) | < 0.0001 | 43.29 | 1.217 (1.148 - 1.290) | <0.0001 |

5. Discussion

Our study revealed that rural living has a protective effect on NAFLD in men and women. This result was confirmed in both the univariate analyses and the multivariate analyses. We showed that the prevalence of NAFLD is significantly lower in people who live in rural areas than in urban areas. One study in China showed that the prevalence of NAFLD was considerably lower in people who lived in rural areas (12.9%) compared with people in urban areas (23%) (11). Urbanization is related to unhealthy lifestyles, which likely played a critical role in the high prevalence of NAFLD in the urban areas. Previous studies showed that the levels of urbanization also played a critical role in the prevalence of NAFLD. Local economic status, social performances, and cultural practices, such as the consumption of a healthy diet, regular exercise, and even living in areas with a healthy environment, can have an effect on health-related practices (12). Other studies showed that living in an urban area of Iran is usually associated with a higher prevalence of psychological disorders (13). On the other hand, psychological disorders have a significant association with NAFLD, although this association may be partly due to the consumption of anti-psychological medications by psychiatric patients (14). Some studies have pointed out the role that vitamin D deficiency has on NAFLD (14). Surveys in northern Iran have reported that there was a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in an urban area of northern Iran than in a rural area (15). These results support our findings about the protective effects of living in rural areas on NAFLD (15, 16).

We also showed that marriage has a high association with NAFLD in men. Thus, it can be considered to be a potential risk factor for NAFLD. However, there was a weak association between marriage and NAFLD detected in women. The association between marriage and NAFLD can be partly mediated by other risk factors for NAFLD, such as age, WC, BP, FBS, and TG. For example, the mean age, WC, SBP, DBP, FBS, and TG were significantly higher in married people than in unmarried people, although married people had a lower HDL. However, this association was present in the multivariate analyses where we removed the effects of the other mediators, although the association was somewhat weaker than in the univariate analyses.

Although previous studies have found that marriage had a protective effect on all case mortality, other studies have reported inconsistent results about the role of marriage on overall health (16-20). Some authors suggested that the beneficial effects that marriage has on health have been diluted because of industrialization and modernization (20, 21). On the other hand, an overestimation of health by married people might help explain the previously reported positive effect that marriage has on health (19). Overall, industrialization, urbanization, and modernization have negative effects on marital quality, family functioning, and spouse support, which can explain the diminishing protection that marriage has on health (19, 20). In developing countries, married people, particularly married men, who have financial problems and household expenses have less interests in engaging in healthy behaviors, including appropriate nutrition, regular exercise, and timely visits to physicians and other healthcare providers. Many married men may have two or even three jobs to earn their livelihood. They generally do not have enough time to exercise or perform other pleasurable activities. They may not eat an appropriate breakfast or eat other meals at an appropriate time.

In this study, we showed that rural living has a protective effect on NAFLD, while marriage can be a potential risk factor for NAFLD. Our results contrast with previous studies about the positive role that marriage plays in health. Although, the risk factors of NAFLD have been evaluated in previous studies, few studies have assessed the association between residency and marriage status with NAFLD. However, the present study had some limitations. We evaluated the associations in a cross-sectional study, which is not an optimal design for establishing cause-and-effect relationships. However, we did evaluate the associations in a large community based on a cohort study data, which can produce reliable results.

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(3):274-85. [PubMed ID: 21623852]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x.

-

2.

Clark JM, Diehl AM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an underrecognized cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis. JAMA. 2003;289(22):3000-4. [PubMed ID: 12799409]. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.22.3000.

-

3.

Farrell GC, Wong VW, Chitturi S. NAFLD in Asia--as common and important as in the West. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(5):307-18. [PubMed ID: 23458891]. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.34.

-

4.

Review T, LaBrecque DR, Abbas Z, Anania F, Ferenci P, Khan AG, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):467-73. [PubMed ID: 24921212]. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000116.

-

5.

Otgonsuren M, Stepanova M, Gerber L, Younossi ZM. Anthropometric and clinical factors associated with mortality in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(4):1132-40. [PubMed ID: 23143735]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-012-2446-3.

-

6.

Speliotes EK, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Vasan RS, Meigs JB, Sahani DV, et al. Fatty liver is associated with dyslipidemia and dysglycemia independent of visceral fat: the Framingham Heart Study. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):1979-87. [PubMed ID: 20336705]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23593.

-

7.

Pagano G, Pacini G, Musso G, Gambino R, Mecca F, Depetris N, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome: further evidence for an etiologic association. Hepatology. 2002;35(2):367-72. [PubMed ID: 11826410]. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.30690.

-

8.

Zamani F, Sohrabi M, Alipour A, Motamed N, Saeedian FS, Pirzad R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cholelithiasis in Amol city, northern Iran: a population based study. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(11):750-4. [PubMed ID: 25365614].

-

9.

Festi D, Schiumerini R, Marzi L, Di Biase AR, Mandolesi D, Montrone L, et al. Review article: the diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease -- availability and accuracy of non-invasive methods. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(4):392-400. [PubMed ID: 23278163]. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12186.

-

10.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640-5. [PubMed ID: 19805654]. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644.

-

11.

Zhou YJ, Li YY, Nie YQ, Ma JX, Lu LG, Shi SL, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and its risk factors in the population of South China. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(47):6419-24. [PubMed ID: 18081233].

-

12.

Zhang X, Wan Y, Zhang S, Lu L, Chen Z, Liu H, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease prevalence in urban school-aged children and adolescents from the Yangtze River delta region: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24(2):281-8. [PubMed ID: 26078245]. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.2.13.

-

13.

Mohammadi MR, Davidian H, Noorbala AA, Malekafzali H, Naghavi HR, Pouretemad HR, et al. An epidemiological survey of psychiatric disorders in Iran. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2005;1:16. [PubMed ID: 16185355]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-1-16.

-

14.

Youssef NA, Abdelmalek MF, Binks M, Guy CD, Omenetti A, Smith AD, et al. Associations of depression, anxiety and antidepressants with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2013;33(7):1062-70. [PubMed ID: 23560860]. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12165.

-

15.

Eliades M, Spyrou E. Vitamin D: a new player in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(6):1718-27. [PubMed ID: 25684936]. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1718.

-

16.

Maddah M, Sharami SH, Neyestani TR. Vitamin D insufficiency among postmenopausal women in urban and rural areas in Guilan, Northern Iran. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(4):386-93. [PubMed ID: 21184380]. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639360903393523.

-

17.

Jaffe DH, Manor O, Eisenbach Z, Neumark YD. The protective effect of marriage on mortality in a dynamic society. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):540-7. [PubMed ID: 17434751]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.12.006.

-

18.

van den Berg GJ, Gupta S. The role of marriage in the causal pathway from economic conditions early in life to mortality. J Health Econ. 2015;40:141-58. [PubMed ID: 25804346]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.02.004.

-

19.

Zheng H, Thomas PA. Marital status, self-rated health, and mortality: overestimation of health or diminishing protection of marriage? J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(1):128-43. [PubMed ID: 23321283]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146512470564.

-

20.

Fu R, Noguchi H. Does Marriage Make Us Healthier? Inter-Country Comparative Evidence from China, Japan, and Korea. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148990. [PubMed ID: 26862896]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148990.

-

21.

Chung W, Kim R. Does marriage really matter to health? Intra- and inter-country evidence from China, Japan, Taiwan, and the Republic of Korea. PLoS One. 2014;9(8). eee104868. [PubMed ID: 25118189]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104868.