Abstract

Context:

Direct acting antivirals (DAAs) have recently emerged as a promising therapeutic regimen for the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, which is a major public health problem. Among the known DAAs, daclatasvir (DCV), an inhibitor of the non-structural 5A protein, has been used in combination with several drugs for treatment of infection with HCV of different genotypes under different conditions. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of combination therapy with DCV.Evidence Acquisition:

We performed a systematic search in PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct and Web of Science with appropriate keywords for DCV. Studies that evaluated any regimen containing DCV and reported the sustained virological response (SVR) 12 weeks after therapy based on the HCV genotype, treatment duration and use of ribavirin (RBV) were included. The selected studies were considered for meta-analysis using STATA 11.0.Results:

We found six different regimens containing DCV: DCV/asunaprevir (ASV), DCV/ASV/beclubavir, DCV/pegylated interferon lambda or alpha/RBV with or without ASV, DCV/simeprevir, DCV/VX-135 and DCV/sofosbuvir (SOF). Most of these regimens were used for the treatment of HCV genotype 1 infections, and in most cases, treatment failure was noted in subtype 1a infections. Among all these regimens, DCV/SOF with or without RBV for 12 or 24 weeks was found to be an efficacious approach for treatment of different types of patients with infections with different HCV genotypes.Conclusions:

Among the treatment regimens containing DCV, DCV/SOF has the highest SVR rate for the treatment of infection with different HCV genotypes in different patient contexts; thus, this regimen shows promise for the treatment of HCV infections.Keywords

Hepatitis C Therapy Daclatasvir Asunaprevir Sofosbuvir Meta-Analysis

1. Context

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has an estimated global prevalence rate of 2.8% and affects more than 185 million people worldwide (1). Chronic hepatitis C infection can lead to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and even death (2). HCV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection are major risk factors for HCC. Moreover, it has been reported that HCV has a higher prevalence than HBV in HCC cases in most European, Americans and North African countries (3, 4). While the incidence rate of HCV is decreasing in some countries, its morbidity and mortality rates are expected to increase during the next few decades (5, 6). HCV-infected patients remain asymptomatic for a long period, as a result of which this disease remains undiagnosed in most patients (7). Fortunately, HCV treatment can majorly decrease its associated complications (8).

The recent revolutionary advances in HCV therapy have completely changed the treatment approaches. In particular, interferon-free regimens with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) are now in use. The main advantages of DAA therapy are its fewer side effects, shorter treatment duration and significantly higher rate of sustained virological response (SVR) (9). Different combinations of DAAs have been used against different HCV genotypes and in different types of patients such as treatment naïve (TN) or treatment experienced (TE), cirrhotic or non-cirrhotic, and liver transplanted (LTx) patients. Among the DAAs in use, daclatasvir (DCV), which inhibits the HCV non-structural (NS) 5A protein, has been used in combination with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) alpha or lambda and ribavirin (RBV) and also with some other DAAs such as asunaprevir (ASV), beclubavir (BCV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) against different HCV genotypes, and they have exhibited different SVR rates (10). There is a growing body of literature about these regimens in different conditions, and there is therefore a need to review these studies in order to determine which regimens are appropriate for specific conditions.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to evaluate effect of different regimens containing DCV on HCV treatment.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Data Resources and Search Strategies

We comprehensively and systematically searched the following electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct and Web of Science. We used appropriate combinations of the following keywords: daclatasvir, Daklinza and BMS-790052. No language limitation was considered in our search strategy. Our last search was performed on July 25, 2016. Moreover, the references of the included papers were evaluated for any related studies that were missed out in the search.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

All clinical trials and cohort studies evaluating HCV treatment regimens containing DCV were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis, and no limitation was placed on the treatment duration. Both journal articles and meeting abstracts were considered.

2.3. Study Selection, Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction

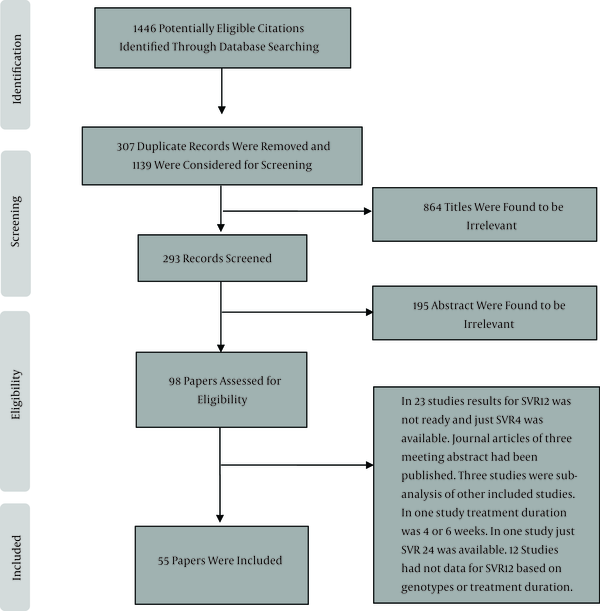

All the reviewing and screening processes in this study were based on the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews (11). We independently investigated the title, abstract and full text of papers identified through the database searches. After each level of screening, we discussed the included and excluded papers and resolved any discrepancies. We performed a critical evaluation of the studies with regard to sample size, selection bias (including the treatment of patients with different degrees of liver disease or patients with a history of previous treatment that could influence the SVR rate) and the SVR rate reported 12 weeks after the end of therapy based on the HCV genotype, treatment duration and use of RBV. We extracted the following data from each of the included studies: publication year, sample size, median or mean age, gender, history of previous treatment, HCV genotypes, cirrhosis status, treatment duration, use of RBV, rate of SVR at post-treatment 12 weeks (henceforth referred to as “12-week SVR rate”) and relapse.

2.4. Data Analysis

All analyses were performed with the STATA software, version 11.0. We used random- or fixed-effect models for meta-analysis of included studies based on the existence of heterogeneity between results of them. Heterogeneity was assessed using chi-squared and I-squared (lies between 0 and 100) tests. P values less than 0.1 were considered to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity in the chi-squared test. Two commands metan and metaprop were used to calculate the pooled 12-week SVR rate and 95% confidence interval (CI). The ftt option was combined with the metaprop command to obtain an admissible CI (12).

3. Results

3.1. Study Screening and Characteristics of the Included Studies

We found 1446 papers through our search of the databases, and after all duplicates were excluded, 1139 papers were considered for screening. After the title and abstract were screened, 98 papers were selected, from which 55 were finally found to be eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). The HCV treatment characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 1 to 4 and in the below sections.

Screening of Articles Based on the PRISMA Statement

Sustained Virological Response Rate for Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection With Daclatasvir Plus Asunaprevir Without Ribavirin

| First Author (Reference No.) | Publication Year | Sample Size | Age (Mean, SD or Median, Range) | Male, No. (%) | Genotype and Subtype | Treatment History | SVR, No. (%) | Relapse, No. (%) | Cirrhosis-Based SVR | Genotype W/O SVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lok, AS (13) | 2012 | 11 | 54 (36 - 61) | 9 (81.81) | 1a:9, 1b:2 | TE | 4 (36.36) | 1 (9.09) | 0/0 | 1a: 7 |

| Chayama, K (14) | 2012 | 10 | 62 (52 - 70) | 2 (20) | 1b: all | TE | 9 (90) | 0 | 0/0 | 1b: 1 |

| Suzuki, Y (15) | 2013 | 21 | 61 (31 - 70) | 8 (38.09) | 1b: all | TE | 19 (90.47) | 0 | 0/0 | 1b: 2 |

| Suzuki, Y (15) | 2013 | 22 | 68 (48 - 75) | 6 (27.27) | 1b: all | -a | 14 (63.63) | 4 (18.18) | 0/0 | 1b: 8 |

| Chayama, K (16) | 2013 | 222 | 62.5 (ND) | 78 (35) | 1b: all | Mixa | 190 (85.58) | ND | ?/22 | 1b: 32 |

| Lok, AS (17) | 2014 | 38 | ND | 24 (63.15) | 1b: all | TE | 27 (71.05) | 1 (2.63) | 0/0 | 1b: 11 |

| Manns, M (18) | 2014 | 205 | 55 (20 - 79) | 101 (49.26) | 1b: all | TN | 185 (90.24) | 5 (2.43) | 29/32 | 1b: 20 |

| Manns, M (18) | 2014 | 205 | 58 (23 - 77) | 58 (28.29) | 1b: all | TE | 168 (81.95) | 7 (3.41) | 104/124 | 1b:37 |

| Manns, M (18) | 2014 | 235 | 60 (24 - 77) | 60 (25.53) | 1b: all | a | 192 (81.70) | 12 (5.10) | 88/111 | 1b: 43 |

| Kumada, H (19) | 2014 | 135 | 64 (24 - 75) | 38 (28.14) | 1b: all | -a | 119 (88.14) | 11 (8.14) | 10/11 | 1b; 16 |

| Kumada, H (19) | 2014 | 87 | 60 (42 - 74) | 39 (44.82) | 1b: all | TE | 70 (80.45) | 6 (6.89) | 10/11 | 1b: 17 |

| Kosaka, K (20) | 2015 | 10 | 62.4 (ND) | 2 (20) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 5) | 8 (80) | 1 (10) | 0/0 | 1b: 2 |

| Iio, E (21) | 2015 | 641 | 71 (33-87) | 279 (43.52) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 319) | 543 (84.71) | ND | ?/216 | 1b: 98 |

| Akuta, N (22) | 2016 | 844 | 69 (25 - 88) | 350 (41.46) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 376) | 737 (87.32) | ND | 737/844 | 1b: 107 |

| Kanda, T (23) | 2016 | 54 | 69.2 (9.1) | 19 (35.18) | 1a: 1, 1b: 53 | Mix (TE: 37) | 51 (94.44) | 0 | 24/25 | 1b: 3 |

| Kinugasa, H (24)b | 2016 | 30 | 63 (26 - 74) | 11 (36.66) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 6) | 25 (83.33) | 1 (3.33) | 0/0 | 1b: 5 |

| Kumada, H (25) | 2016 | 119 | 57 (20 - 70) | 48 (40.33) | 1b: all | TN | 106 (89.07) | 10 (8.40) | 0/0 | 1b: 13 |

| Kumada, H (25) | 2016 | 22 | 65 (45 - 75) | 7 (31.88) | 1b: all | TE | 21 (95.45) | 1 (4.54) | 0/0 | 1b: 1 |

| Miyazaki, R (26)c | 2016 | 10 | 68.1 (ND) | 7 (70) | 1b: all | ND | 10 (100) | 0 | ND | None |

| Ogawa, E (27) | 2016 | 321 | 71 (26 - 87) | 100 (31.15) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 150)a | 290 (89.50) | 12 (3.70) | 115/127 | 1b: 34 |

| Suda, G (28)c | 2016 | 21 | 63 (50 - 79) | 15 (71.42) | 1b:19, 1a:1, ?:1 | Mix (TE: 7) | 20 (95.23) | 1 (4.76) | 4/4 | ND |

| Toyoda, H (29)c | 2016 | 28 | 65.6 (9.5) | 16 (57.14) | 1b: all | ND | 28 (100) | 0 | 11/11 | None |

| Toyoda, H (29) | 2016 | 56 | 65.9 (11.6) | 29 (51.78) | 1b: all | ND | 54 (96.42) | 0 | ?/22 | 1b: 2 |

| Wei, L (30) | 2016 | 159 | ND | ND | 1b: all | -a | 145 (91.19) | 2 (1.25) | 47/52 | 1b: 14 |

| Ikeda, H (31) | 2016 | 138 | 73 (40 - 87) | 52 (37.7) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 71)a | 125 (90.57) | 4 (2.89) | ND | 1b:13 |

| Nam, HC (32) | 2016 | 8 | 65.75 (10.22) | 3 (37.5) | 1b: all | Mix (TE: 3) | 7 (87.5) | 0 | 7/8 | 1b: 1 |

| Nagao, Y (33)d | 2016 | 7 | 73.9 (ND) | 4 (57.14) | 1b:all | Mix (TE: 5) | 7 (100) | 0 | 1/1 | None |

Sustained Virological Response Rate for Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection With Daclatasvir, Asunaprevir and Beclubavir

| First Author (Reference No.) | Publication Year | Sample Size | Age (Mean, SD or Median, Range) | Male, No. (%) | Genotype and Subtype | Beclubavir Dose, mg | Duration (Weeks) | RBV | Treatment History | SVR, No. (%) | Relapse, No. (%) | Cirrhosis-Based SVR | Genotypes W/O SVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everson, GT (34) | 2014 | 16 | 49 (44 - 61) | 10 (62.5) | 1a: 12, 1b: 4 | 75 | 12 | No | TN | 15 (93.75) | 0 | 0/0 | 1a: 1 |

| Everson, GT (34) | 2014 | 16 | 47 (24 - 67) | 7 (43.75) | 1a: 12, 1b: 4 | 75 | 24 | No | TN | 15 (93.75) | 0 | 0/0 | 1a: 1 |

| Everson, GT (34) | 2014 | 16 | 55 (25 - 67) | 9 (56.25) | 11a:12, 1b:4 | 150 | 12 | No | TN | 15 (93.75) | 0 | 0/0 | 1b: 1 |

| Everson, GT (34) | 2014 | 18 | 49 (29 - 68) | 13 (72.22) | 1a: 13, 1b: 5 | 150 | 24 | No | TN | 16 (88.88) | 1 (5.55) | 0/0 | 1a: 2 |

| Poordad, F (35) | 2015 | 312 | 53.5 (19 - 77) | 175 (56.1) | 1a: 229, 1b: 83 | 75 | 12 | No | TN | 287 (91.98) | 15 (4.80) | 0/0 | 1a: 23, 1b: 2 |

| Poordad, F (35) | 2015 | 103 | 57.0 (22 - 69) | 64 (62.1) | 1a: 75, 1b: 28 | 75 | 12 | No | TE | 92 (89.32) | 6 (5.82) | 0/0 | 1a: 11 |

| Hassanein, T (36) | 2015 | 11 | 56.0 (37 - 66) | 7 (63.6) | 4: all | 75 | 12 | No | TN | 11 (100) | 0 | 0/0 | None |

| Hassanein, T (36) | 2015 | 10 | 50.0 (22 - 57) | 6 (60.0) | 4: all | 150 | 12 | No | TN | 10 (100) | 0 | 0/0 | None |

| Muir, AJ (37) | 2015 | 57 | 58 (25 - 75) | 39 (68.42) | 1a: 40, 1b: 17 | 75 | 12 | No | TN | 53 (92.98) | 4 (7.01) | 53/57 | 1a: 4 |

| Muir, AJ (37) | 2015 | 55 | 59 (35-73) | 35 (63.63) | 1a: 39, 1b: 15, 6:1 | 75 | 12 | Yes | TN | 54 (98.18) | 0 | 54/55 | 1a: 1 |

| Muir, AJ (37) | 2015 | 45 | 59 (19 - 76) | 32 (71.11) | 1a: 35, 1b: 17 | 75 | 12 | No | TE | 39 (86.66) | 5 (11.11) | 39/45 | 1a: 5, 1b: 1 |

| Muir, AJ (37) | 2015 | 45 | 60 (48 - 73) | 27 (60.00) | 1a: 35, 1b: 17 | 75 | 12 | Yes | TE | 42 (93.33) | 1 (2.22) | 42/45 | 1a: 3 |

| Everson, GT (38) | 2016 | 80 | 54 (23 - 68) | 55 (68.75) | 1a: 67, 1b: 13 | 75 | 12 | No | TN | 71 (88.75) | 4 (5.00) | 8/8 | 1a: 8, 1b: 1 |

| Everson, GT (38) | 2016 | 86 | 54 (23 - 69) | 57 (66.27) | 1a: 69, 1b: 17 | 150 | 12 | No | TN | 77 (89.53) | 2 (2.32) | 5/7 | 1a: 7, 1b: 2 |

| Everson, GT (38) | 2016 | 21 | 50 (23 - 64) | 9 (42.85) | 1a: 19, 1b: 2 | 75 | 24 | yes | TN | 18 (78.26) | 0 | 1/1 | 1a: 3, 1b: |

Sustained Virological Response Rate for Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection With Daclatasvir, Pegylated Interferon, and Ribavirin With or Without Asunaprevir

| First Author (Reference No.) | Publication Year | Sample Size | Age (Mean, SD or Median, Range) | Male, No. (%) | Genotype and Subtype | Duration (Weeks) | Interferon | Asunaprevir | Treatment History | SVR, No. (%) | Relapse, No. (%) | Cirrhosis-Based SVR | Genotypes W/O SVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pol, S (39) | 2012 | 12 | 51 (43 - 67) | 7 (58.33) | 1a:9, 1b:3 | 48 | Alpha 2a | No | TNa | 10 (83.33) | 1 (8.33) | 0/0 | 1a: 2 |

| Lok, AS (13) | 2012 | 10 | 56.5 (38 - 63) | 4 (40) | 1a:9, 1b:1 | 24 | Alpha 2a | Yes | TE | 10 (100) | 0 | 0/0 | None |

| Lok, AS (17) | 2014 | 41 | ND | 22 (53.65) | 1a:36, 1b: 5 | 24 | Alpha 2a | Yesb | TE | 39 (95.12) | 2 (4.87) | 0/0 | 1a: 2 |

| Dore, GJ (40) | 2015 | 24 | 51.5 (30 - 64) | 13 (54.16) | 2: all | 12 | Alpha 2a | No | ND | 18 (75) | ND | 0/0 | 2: 6 |

| Dore, GJ (40) | 2015 | 23 | 52 (25 - 64) | 15 (65.21) | 2: all | 16 | Alpha 2a | No | ND | 18 (78.26) | ND | 0/0 | 2: 5 |

| Dore, GJ (40) | 2015 | 26 | 46 (28 - 61) | 19 (73.07) | 3: all | 12 | Alpha 2a | No | ND | 16 (61.53) | ND | ?/7 | 3: 10 |

| Dore, GJ (40) | 2015 | 27 | 44 (31 - 67) | 22 (81.48) | 3: all | 16 | Alpha 2a | No | ND | 19 (70.37) | ND | ?/4 | 3:8 |

| Jensen, D (41) | 2015 | 354 | 54 (19 - 76) | 240 (67.8) | 1a:176, 1b:178 | 24 | Alpha 2a | Yes | TE | 329 (92.9) | 8 (2.25) | 66/73 | 1A: 23, 1B: 2 |

| Jensen, D (41) | 2015 | 44 | 52 (20 - 71) | 33 (75.0) | 4: all | 24 | Alpha 2a | Yes | TE | 43 (97.7) | 0 | 19/20 | 4: 1 |

| Piroth, L (42)c | 2015 | 37 | ND | ND | 1: all subtypes: ND | 24d | Alpha 2a | Yes | TE | 35 (94.59) | 0 | 13/14 | ND |

| Piroth, L (31)c | 2015 | 38 | ND | ND | 4: all | 24d | Alpha 2a | Yes | TE | 37 (97.36) | 0 | 12/13 | 4: 1 |

| Hezode, C (43) | 2015 | 82 | 48.5 (20 - 71) | 61 (74.4) | 1a: 26, 4: 56 | 24 | Alpha 2a | No | TN | 56 (68.29) e | ND | ?/9 | ND |

| Jacobson, I (44) | 2016 | 268 | 46.0 (18 - 71) | 159 (59.3) | 1b | 24f | Alpha 2a | No | TN | 228 (85.07) | 12 (4.47) | 20/26 | 1b: 40 |

| Jacobson, I (44) | 2016 | 134 | 49.0 (19 - 67) | 98 (73.1) | 1a | 24f | Alpha 2a | No | TN | 87 (64.92) | ND | ?/16 | 1a: 47 |

| Flisiak, R (45) | 2016 | 294 | 50 (19 - 74) | 157 (53.4) | 1b | 24g | Lambda 1a | No | Mix (TE = 59) | 261 (88.87) | 17 (5.78) | ?/20 | 1b: 33 |

| Santagostino, E (46)h | 2016 | 12 | 46.5 (27 - 56) | 12 (100) | 2: 2, 3: 10 | 24 | Lambda 1a | NO | Mix (TE = 1) | 11 (91.66) | 1 (8.33) | 2/2 | 3: 1 |

| Santagostino, E (46)h | 2016 | 39 | 43.0 (24 - 69) | 39 (100) | 1b | 24g | Lambda 1a | NO | Mix (TE = 8) | 35 (89.74) | 4 (10.25) |

Sustained Virological Response Rate for Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection With Daclatasvir Plus Sofosbuvir

| First Author (Reference no.) | Publication Year | Sample Size | Group | Genotype | RBV | Duration (Weeks) | Treatment History | SVR, No. (%) | Relapse, No. (%) | Cirrhosis-Based SVR | Genotypes W/O SVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulkowski, MS (54) | 2014 | 29 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: 15, 2: 9, 3: 5 | Yes | 24 | TN | 27 (93.10) | 0 | 0/0 | 3: 2 |

| Sulkowski, MS (54) | 2014 | 59 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: 29, 2: 17, 3: 13 | No | 24 | TN | 57 (96.61) | 1 (1.69) | 0/0 | 2: 2 |

| Sulkowski, MS (54) | 2014 | 41 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | Yes | 12 | TN | 39 (95.12) | 0 | 0/0 | 1: 2 |

| Sulkowski, MS (54) | 2014 | 41 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | No | 12 | TN | 41 (100) | 0 | 0/0 | None |

| Sulkowski, MS (54) | 2014 | 21 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | No | 24 | TE | 21 (100) | 0 | 0/0 | None |

| Sulkowski, MS (54) | 2014 | 20 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | Yes | 24 | TE | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 0/0 | 1: 1 |

| Nelson, DR (75) | 2015 | 101 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 3:all | No | 12 | TN | 91 (90.09) | 9 (8.91) | 11/22 | 3: 10 |

| Nelson, DR (75) | 2015 | 51 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 3:all | No | 12 | TE | 44 (86.27) | 7 (13.72) | 5/8 | 3: 7 |

| Pol, S (55) | 2015 | 53 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | No | 12 | Mix | 45 (84.90) | ND | ND | 1: 8 |

| Pol, S (55) | 2015 | 11 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | Yes | 12 | Mix | 11 (100) | 0 | ND | None |

| Pol, S (55) | 2015 | 184 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | No | 24 | Mix | 172 (93.47) | ND | ND | 1: 12 |

| Pol, S (55) | 2015 | 62 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | Yes | 24 | Mix | 61 (98.38) | ND | ND | 1: 1 |

| Leroy, V (76) | 2016 | 24 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 3: all | Yes | 12 | Mix (TE: 18) | 21 (87.50) | 2 (8.33) | 15/18 | 3: 3 |

| Leroy, V (76) | 2016 | 26 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 3: all | Yes | 16 | Mix (TE: 19) | 24 (92.30) | 2 (7.69) | 16/18 | 3: 2 |

| Mangia, A (77) | 2016 | 8 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 2: all | no | 12 | Mix (TE: 3) | 8 (100) | 0 | 0/0 | None |

| Mangia, A (77) | 2016 | 11 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 2: all | no | 24 | Mix (TE: 8) | 11 (100) | 0 | 11/11 | None |

| Ji, D (78) | 2016 | 46 | Mono infected w/o SLD | 1: all | NO | 12 | TE | 46 (100) | 0 | 27/27 | None |

| Welzel, TM (59)a,b | 2015 | 51 | SLD | 1: 31, 2:2, 3: 13, 4:5 | Yes | Mostly 24 | ND | 48 (94.11) | ND | 40/42 | 1: 1, 3: 2 |

| Hézode, C (79)c | 2015 | 77 | SLD | 4: 63, 5: 10, 6: 4 | No | 12 | Mix | 67(87.01) | ND | ND | 4: 10 |

| Hézode, C (79)c | 2015 | 8 | SLD | 4: all | Yes | 12 | Mix | 7 (87.50) | ND | ND | 4: 1 |

| Hézode, C (79)c | 2015 | 125 | SLD | 4: 110, 5: 14, 6: 1 | No | 24 | Mix | 102 (81.60) | ND | ND | 4: 8 |

| Hézode, C (79) | 2015 | 32 | SLD | 4: 31, 5: 1 | Yes | 24 | Mix | 31 (96.87) | ND | ND | 4: 1 |

| Welzel, TM (59)a,d | 2015 | 93 | SLD | 1: 78, 3: 11, 4:4 | No | Mostly 24 | ND | 92 (98.92) | ND | 64/65 | 1: 1 |

| Poordad, F (58) | 2016 | 60 | SLD | 1: 45, 2:5, 3:6, 4:4 | Yes | 12 | Mix (TE = 36) | 50 (83.33) | 9 (15) | 50/60 | 1: 8, 2: 1, 3: 1 |

| Foster GR (57) | 2016 | 159 | SLD | 1: 41, 3: 11 | Yes | 12 | Mix | 122 (76.72) | ND | 122/152 | 1: 5, 3: 32 |

| Foster GR (57) | 2016 | 12 | SLD | 1: 5, 3:7 | No | 12 | MIX | 8 (66.66) | ND | 8/12 | 1:2, 3: 2 |

| Wyles, DL (56) | 2015 | 101 | HIV | 1: 83, 2: 11, 3: 6, 4:1 | No | 12 | TN | 98 (97.02) | 1 (0.99) | 8/9 | 1: 3 |

| Wyles, DL (56) | 2015 | 50 | HIV | 1: 41, 2: 6, 3: 3, | No | 8 | TN | 38 (76.00) | 10 (19.23) | 3/5 | 1: 10, 2: 1, 3: 1 |

| Wyles, DL (56) | 2015 | 52 | HIV | 1: 44, 2: 2, 3: 4, 4: 2 | No | 12 | TE | 51 (98.07) | 1 (1.92) | 14/15 | 1:1 |

| Rockstroh, JK (60)a | 2015 | 34 | HIV and SLD | 1: 24, 3:6, 4: 3, ?:1 | No | Mostly 24 | Mix (TE = 22) | 31 (91.17) | 1 (2.94) | 30/33 | 1;2, 3:1 |

| Rockstroh, JK (60)a | 2015 | 15 | HIV and SLD | 1:8, 3: 5, ?: 2 | Yes | Mostly 24 | Mix (TE = 7) | 14 (93.33) | 0 | 13/12 | ?:1 |

| Mandorfer, M (80)e | 2016 | 31 | HIV and SLD | 1: 21, 3:7, 4: 3 | No | 12 or 24 | Mix (TE = 16) | 31 (100) | 0 | 16/16 | None |

| Herzer, K (81)a | 2015 | 62 | LTx | 1:58, 3:4 | Yes | 24 | Mix (TE: 19) | 54 (87.02) | 0 | 9/11 | 1:7, 3: 1 |

| Herzer, K (81)a | 2015 | 25 | LTx | 1:18, 3: 4, 4:2 ?:1 | No | 24 | Mix (TE: 41) | 20 (80.00) | 0 | 21/24 | 1:2, ?: 1 |

| Coilly, A (82) | 2016 | 21 | LTx | 1: 18, 3: 2, 4: 1, | Yes | 12 | Mix (TE: 7) | 21 (100) | 0 | 6/6 d | None |

| Coilly, A (82) | 2016 | 4 | LTx | 1: 3, 3: 1 | No | 12 | Mix (TE: 2) | 3 (75) | 0 | 1/1 d | 1:1 |

| Coilly, A (82) | 2016 | 68 | LTx | 1: 55, 3: 5, 4: 7, 5: 1 | No | 24 | Mix (TE: 32) | 66 (97.05) | 0 | ND | 4: 1, ?: 1 |

| Coilly, A (82) | 2016 | 44 | LTx | 1: 33, 3: 7, 4: 4 | Yes | 24 | Mix (TE: 27) | 42 (95.45) | 0 | ND | ND |

| Fontana, RJ (49)f | 2016 | 57 | LTx | 1: 53, 2: 1, 3: 1, 4: 2 | No | up to 24 | ND | 43 (75.43) | 0 | ND | 1:7, Other: ND |

| Fontana, RJ (49)f | 2016 | 20 | LTx | 1: 18, 2: 1, 3: 1, 4: 1 | Yes | up to 24 | ND | 9 (36.00) | 0 | ND | ND |

3.2. Evaluation of the Regimens

We found the following HCV treatment regimens containing DCV: DCV/ASV, DCV/ASV/BCV, DCV/PEG-IFN lambda or alpha/RBV with or without ASV, DCV/SMV, DCV/VX-135, and DCV/SOF. RBV has been used in some of these regimens. A summary of the results of the meta-analysis of different regimens is presented in Table 5. The results of other studies that were not included in the meta-analysis can be found in the below sections or in Tables 1 - 4.

Pooled Sustained Virological Response Rate for Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Patients With Daclatasvir-Based Regimens

| Regimen | Duration | Genotype | Group | Number of Included Studies or Arms | Total Sample Size | SVR (%) | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCV/ASV | 24 weeks | 1b | TE | 8 | 570 | 86.74 | 81.79 | 91.68 |

| DCV/ASV | 24 weeks | 1b | TN | 4 | 513 | 91.04 | 88.57 | 93.51 |

| DCV/ASV/BCV (75 mg) | 12 weeks | 1b | TN | 3 | 113 | 99.00 | 95.00 | 100 |

| DCV/ASV/BCV (75 mg) | 12 weeks | 1a | TN | 4 | 348 | 89.70 | 86.51 | 92.89 |

| DCV (first 12 weeks)/PEG-IFN Lambda/RBV | 24 weeks | 1b | Mix | 2 | 333 | 88.89 | 85.52 | 92.26 |

| DCV/ASV/PEG-IFN alpha/RBV | 24 weeks | 1a | TN | 3 | 249 | 90.41 | 86.75 | 94.06 |

| DCV/ASV/PEG-IFN alpha/RBV | 24 weeks | 4 | TE | 2 | 82 | 98.00 | 93.00 | 100 |

| DCV/SOF | 12 weeks | 1 | Mix (W/O SLD) | 5 | 267 | 97.00 | 92.00 | 100 |

| DCV/SOF/RBV | 12 weeks | 1 | Mix (W/O SLD) | 2 | 52 | 97.00 | 90.00 | 100 |

| DCV/SOF | 24 weeks | 1 | Mix (W/O SLD) | 3 | 224 | 96.00 | 93.00 | 99.00 |

| DCV/SOF/RBV | 24 weeks | 1 | Mix (W/O SLD) | 3 | 97 | 100 | 96.00 | 100 |

| DCV/SOF/RBV | 12 weeks | 1 | Mix (SLD) | 2 | 86 | 85.00 | 76.00 | 92.00 |

| DCV/SOF | 24 weeks | 1 | Mix (SLD) | 2 | 102 | 98.00 | 94.00 | 100 |

3.2.1. Daclatasvir/Asunaprevir

The characteristics of the studies on the DCV/ASV/BCV regimen are shown in Table 1. We found 27 papers that evaluated the effects of a 24-week treatment with DCV/ASV without RBV in HCV genotype 1-infected patients. Most of the studies were on subtype 1b, and only three of the studies were on subtype 1a (13, 24, 28). Only studies that reported the 12-week SVR rate based on HCV subtypes and treatment history were included in this meta-analysis. Moreover, studies with a sample size of less than 10 were excluded. There was no enough study for genotype 1a based on the mentioned criteria and we could not do meta-analysis for this subtype. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis of the effect of this regimen on infection with HCV subtype 1b based on previous history of treatment. For TE patients infected with HCV subtype 1b, eight studies (14, 15, 17-19, 23, 25, 27) with a total sample size of 570 were included. We used the random-effect model (χ2 = 18.34, P = 0.01, I2 = 61.8%, τ2 = 28.05) and the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 86.74% (95% CI = 81.79 - 91.68).(Forest Plot 1 in the supplementary file). There was no publication bias, based on the results of Egger’s (P = 0.875) and Begg’s (P = 0.805) tests. Furthermore, four studies (18, 23, 25, 27) with a total sample size of 513 were included for meta-analysis of the 24-week DCV/ASV regimen without RBV in TN patients infected with HCV subtype 1b. No heterogeneity was found between the results of these studies (χ2 = 1.42, P = 0.70, I2 = 0%). The pooled 12-week SVR rate was 91.04% (95% CI = 88.57 - 93.51) (Forest Plot 2 in the supplementary file). We found no publication bias, based on the results of Egger’s (P = 0.822) and Begg’s (P = 0.497) tests.

3.2.2. Daclatasvir/Asunaprevir/Beclubavir

The characteristics of the studies on the DCV/ASV/BCV regimen are shown in Table 2. Different doses of BCV (75 or 150 mg) with or without RBV were administered for 12 or 24 weeks in TN and TE patients infected with HCV genotype 1a, 1b and 4. The meta-analysis only included studies with a sample size of more than 10 patients that reported the 12-week SVR rate separately based on the HCV genotype, use of RBV, treatment duration, history of treatment and dose of BCV (75 or 150 mg). For genotype 1b-infected TN patients who underwent 12 weeks of the aforementioned regimen (75 mg BCV) without RBV, three studies (35, 37, 38) (total sample size = 113) were included. We used fixed-effect model (χ2 = 1.48, P = 0.48, I2 = 0%), and the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 99.00 (95% CI = 95.00 - 100) (Forest Plot 3 in the supplementary file). Moreover, no publication bias was found based on Egger’s (P = 0.811) and Begg’s (P = 0.602) tests. For genotype 1a-infected TN patients who were administered 75 mg BCV without RBV for 12 weeks, four studies (34, 35, 37, 38) (total sample size = 348) were included in the meta-analysis. In the case of these studies, too, we used the fixed-effect model (χ2 = 0.25, P = 0.96, I2 = 0%), and the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 89.70 (95% CI = 86.51 - 92.89) (Forest Plot 4 in the supplementary file). There was no publication bias based on the results of both Egger’s (P = 0.991) and Begg’s (P = 1) tests.

3.2.3. Daclatasvir/Pegylated Interferon/Ribavirin With or Without Asunaprevir

Table 3 shows the characteristics of studies on the DCV/PEG-IFN/RBV regimen with or without ASV We found two studies (45, 46) which investigated the effect of this regimen on patients with genotype 1b infection (total sample size = 333). In these two studies, the patients were administered PEG-IFN lambda for 24 weeks. In the first 12 weeks, they were also administered DCV. We found no heterogeneity between these studies (χ2 = 0.04, P = 0.85, I2 = 0%) and based on the fixed-effect model the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 88.89 (95% CI = 85.52 - 92.26). No publication bias was found based on the results of Begg’s test (P = 0.317). Egger’s test was not performed because the number of studies was too low.

Three studies (17, 41, 42) (total sample size = 249) were included in the meta-analysis of the DCV/PEG-IFN alpha/RBV regimen administered for 24 weeks in genotype 1a HCV-infected patients. All the patients had previously undergone treatment for HCV infection. In one of these three studies (17), approximately half of the patients were administered ASV BD, and the other half were administered ASV QD. We found no heterogeneity between the results of these studies (χ2 = 4.11, P = 0.12, I2 = 51.3%) and based on the fixed-effect model, the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 90.41 (95% CI = 86.75 - 94.06). The P values derived from Begg’s and Egger’s tests were 0.602 and 0.048 respectively.

The PEG-IFN/DCV regimen has been used in patients with genotype 2, 3 and 4 HCV infection (40-42). We found two studies (total sample size = 82) that evaluated this regimen; these studies also investigated the effects of DCV on TE patients infected with HCV genotype 4. No heterogeneity was found between the results of these studies (χ2 = 0.01, P = 0.92, I2 = 0%). The pooled 12-week SVR rate for this regimen was 98.00% (95% CI = 93.00 - 100), and Begg’s test did not reveal a publication bias (P = 0.317).

Continuation of treatment with DCV and PEG-IFN in some studies was based on acquiring a protocol defied response (PDR), which is defined as an HCV-RNA level less than the lower limit of quantification at week 4 and undetectable at week 10 of treatment. After PDR was examined, the patients were re-randomized to determine whether they would receive the PEG-IFN with DCV or placebo treatment. In one of the studies, 145 patients (genotype 1a = 113, genotype 1b = 31 and genotype 4 =13) were treated with DCV (60 mg) plus PEG-IFN alpha: 12-week SVR was achieved in 88 (60.3%) genotype 1 and 12 (100%) genotype 4 patients (47). In another study, TN patients (n = 8) and prior non-responders (n = 9) were treated with DCV (60 mg) and PEG-IFN alpha for 24 or 48 weeks based on the PDR. A 24-week SVR was achieved in all the TN patients and 7 of the 9 prior non-responders (48). Because treatment was continued based on PDR for 24 or 48 weeks in these studies, we were unable to determine the 12-week SVR rate for treatment with PEG-IFN alpha/DCV, and therefore, we did not include these studies in our meta-analysis.

3.2.4. Daclatasvir/Simeprevir

DCV/SMV with or without RBV has been used for the treatment of HCV genotype 1 infection in different settings, including in LTx (49), TN and TE patients (50), and also in a kidney transplant patient (51). Because of differences in the duration of therapy (12 or 24 weeks), the use of RBV, history of previous treatment and subtypes (1a or 1b), we preferred not to pool the data of these three studies. Eighteen LTx patients were treated with DCV/SOF with (n = 12) or without (n = 6) RBV for up to 24 weeks: the 12-week SVR rate was 50.00% and 83.33% in the with and without RBV groups respectively (49). Zeuzem et al. (50) reported a 12-week SVR rate of 84.9% and 74.5% in TN patients treated with DCV/SMV and DCV/SMV/RBV respectively. For null responders, they reported a 12-week SVR rate of 69.60% and 95.00% for the DCV/SMV and DCV/SMV/RBV treatments respectively.

3.2.5. Daclatasvir/VX-135

The DCV/VX-135 combination has been evaluated in a phase 2a clinical trial of TN patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. VX-135 at a dose of 100 mg (n = 11) or 200 mg (n = 12) was administered with DCV (60 mg) for 12 weeks. A 12-week SVR rate of 73% and 83% was achieved in the 100 and 200 mg VX-135 groups respectively (52).

3.2.6. Daclatasvir/Sofosbuvir

The characteristics of the studies on the DCV/SOF regimen with or without RBV are shown in Table 4. In order to conduct a meta-analysis of these studies, we categorized them into three groups. Group A includes studies that evaluated the effect of the aforementioned regimen on patients without severe liver disease (SLD). As seen in Table 4, most of the patients in this group did not have cirrhosis or had compensated cirrhosis. Moreover, there are probably a few cases of decompensated cirrhosis in some of the study arms in this group, but we were unable to exclude them. Therefore, we included these studies in the meta-analysis of group A. Group B includes patients with SLD, most of whom had decompensated cirrhosis and some other were at a high risk of hepatic decompensation or death within 12 months if left untreated. As international guidelines suggest that patients with HIV/HCV co-infection should not be considered as a special population for DAA treatment (53), we included studies on these patients in either group A or B, according to the liver status. Finally, Group C includes studies on LTx patients. We have only presented the studies in this group in Table 4. A meta-analysis of these studies will be published in our future work on the use of DAAs in LTx patients.

For conducting the meta-analysis in each group, we need to know the 12-week SVR rate based on the HCV genotype, the use of RBV and treatment duration. Therefore, we did not include studies that did not report these data. However, because of the low number of studies in each meta-analysis, we did not consider history of previous treatment and subtypes here. On the other hand, studies with a sample size of less than 10 were not included in the meta-analysis. All these data are presented in detail in Table 4. Based on the aforementioned criteria for meta-analyses and the available studies, we could only conduct a meta-analysis for DCV/SOF in patients infected with HCV genotype 1.

3.2.6.1. Daclatasvir/Sofosbuvir in Patients Without Severe Liver Disease (Group A)

For the DCV/SOF regimen without RBV in genotype 1 HCV-infected patients, we included four studies (54, 55, 56, 78) with five different arms (total sample size = 267): There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (χ2 = 14.80, P = 0.01, I2 = 72.97%) and based on the random-effect model, the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 97% (95% CI = 92.00 - 100.00%). No publication bias was found based on the results of Begg’s test (P = 0.32) and Egger’s test (P = 0.77).

For the 12-week DCV/SOF/RBV regimen in HCV genotype 1-infected patients, we found two studies with a total sample size of 52 (55, 56). There was no heterogeneity between these studies (χ2 = 0.02, P = 0.88, I2 = 0%) and based on the fixed-effect model the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 97.00% (95% CI = 90.00 - 100.00). (Forest Plot 9 in the supplementary file). Moreover, there was no publication bias according to the results of Begg’s test (P = 0.31).

We found two studies (three different arms) that evaluated a 24-week DCV/SOF regimen in HCV genotype 1-infected patients (54, 55). The total sample size was 224. There was no heterogeneity between the studies (χ2 = 4.34, P = 0.11, I2 = 53.90%). Based on the fixed-effect model we calculated the 12-week SVR rate to be 96.00% (95% CI = 93.00 - 99.00). Moreover, we did not find a publication bias (Begg’s test, P = 0.60; Egger’s test, P = 0.09) (Forest Plot 10 in the supplementary file).

Two studies (three different arms) with total sample size of 97 patients were included for meta-analysis of the 24-week DCV/SOF/RBV regimen in HCV genotype 1-infected patients (54, 55). Based on the fixed-effect model, there was no heterogeneity between the studies (χ2 = 0.13, P = 0.94, I2 = 0%), and the 12-week SVR rate was 100.00% (95% CI = 96.00 - 100.00) (Forest Plot 11 in the supplementary file). We found no publication bias according to the results of Begg’s test (P = 0.60) and Egger’s test (P = 0.11).

3.2.6.2. Daclatasvir/Sofosbuvir in Patients With Severe Liver Disease (Group B)

Foster et al. (57) treated five SLD patients with genotype 1 HCV infection with the DCV/SOF regimen for 12 weeks: the 12-week SVR rate was reported in three cases (60.00%, 95% CI = 20.94 - 90. 56). We found no similar studies that could be used for a meta-analysis.

Two studies (n = 86) were included in the meta-analysis of the 12-week DCV/SOF/RBV regimen in HCV genotype 1-infected SLD patients (58, 57). There was no heterogeneity between the studies (χ2 = 0.07, P = 0.79, I2 = 0%) and based on fixed-effect model, the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 85.00% (95% CI = 76.00 - 92.00) (Forest Plot 12 in the supplementary file). No publication bias was found based on Begg’s Test (P = 0.31).

We found two studies (n = 102) that evaluated the 24-week DCV/SFO regimen in HCV genotype 1-infected SLD patients (59, 58). Based on the fixed-effect model, there was no heterogeneity between these studies (χ2 = 0.09, P = 0.76, I2 = 0); moreover, the pooled 12-week SVR rate was 98.00% (95% CI = 94.00 - 100) (Forest Plot 13 in the supplementary file). No publication bias was found based on Begg’s test (P = 0.31).

One study (59) with a sample size of 31 patients with HCV genotype 1 infection with SLD evaluated the effect of the DCV/SOF/RBV regimen for 24 weeks: the 12-week SVR rate reported was 96.77% (95% CI = 85.89 - 99.64).

4. Conclusions

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of all HCV treatment regimens that include DCV. As mentioned before, DCV has been used in combination with PEG-IFN alpha, lambda and other DAAs such as ASV, BCV, SMV, VX-135 and SOF. Here, we have analyzed the studies based on the regimen used and HCV genotype.

Combination therapy with PEG-IFN alpha/RBV for 48 weeks has been considered as a standard of care treatment (SOC) and is associated with an SVR rate of 50% in HCV genotype 1-infected patients. The success of this SOC is dependent on many viral as well as patient factors such as the HCV genotype and interleukin 28B; moreover, it is also associated with several side effects. Based on new research on the HCV replication cycle, drugs which act directly on the viral proteins (DAAs, as described before) have been developed. These DAAs have completely changed the approach of HCV therapy. In this regimen, DAAs of the same or different classes are introduced one after another in close succession. Each class of DAAs targets a specific viral protein such as NS3/4A, NS5A and NS5B (9).

DCV targets NS5A, which has significant effects on viral replication and interaction with host cells. The first clinical results for DCV were reported in 2010 by a researcher at Bristol Mayer Squibb (BMS): in a phase 1 clinical trial: a reduction of 3.3 log10 was observed in the mean viral load of patients 24 h after administration of a single 100-mg dose of DCV, which was sustained for an additional 120 hours (61). As the enzymatic activity of the NS5A protein is not yet clearly understood, the exact mechanism underlying the inhibition of the function of this protein by DCV is not well understood yet. However, it is believed that DCV modulates the NS5A phosphorylation status and can interfere with the function of new HCV replication complexes, but it does not affect the pre-formed HCV complexes (62). The introduction of an NS5A inhibitor is a valuable contribution to HCV therapy, but this drug needs to be combined with PEG-IFN or other DAAs to overcome drug resistance, increase antiviral efficacy and decrease side effects (63). DCV is metabolized by liver CYP3A4 and is directly excreted via the biliary system. Single-dose pharmacokinetic studies have shown that DCV is well tolerated in patients with liver or renal failure without the need for dose adjustment (64, 65).

BMS-650032 or ASV, which is an HCV NS3 protease inhibitor, has shown high treatment efficacy when used in combination with DCV and/or PEG-IFN in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 (13, 66). DCV/ASV has been mainly used in patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and mainly in Japanese studies. Further, subtype 1a has been evaluated in only a few studies, and it seems that this regimen is appropriate only for HCV subtype 1b. The treatment duration in all studies was 24 weeks, and RBV was not used in any of the studies. Our meta-analysis showed that the 12-week SVR rate for TN and TE patients with HCV genotype 1 infection was 91% and 87% respectively. In a network meta-analysis, the 24-week DCV/ASV regimen was evaluated in TN patients (two studies, n = 265) and TE patients (two studies, n = 233) with HCV genotype 1 and 4 infection: the 12-week SVR rate reported was 83.07 (95% CI = 75.99 - 90.00) and 62.85% (95% CI = 15.23 - 100.00) for TN and TE patients respectively (53). A considerable increase in the SVR rate was observed with these regimens in comparison with the SOC treatment. However, a more efficacious treatment regimen with a higher SVR rate is required.

BCV is another product of BMS that inhibits the HCV NS5B protein (67). Different doses of BCV (75 mg or 150 mg) have been used in combination with DCV and ASV. The addition of this drug to the DCV/ASV regimen was found to improve the SVR rate in HCV-infected patients. This 12- or 24-week treatment regimen has been mainly used for the treatment of patients infected with HCV genotype 1 (subtypes 1a and 1b) and 4. Furthermore, RBV has also been added to this regimen in some studies. Most cases of treatment failures in these studies were found in subtype 1a infections. Our meta-analysis showed that a 12-week DCV/ASV/BCV regimen without RBV can provide a 12-week SVR rate of 89% and 99% for TN patients infected with HCV genotype 1a and 1b respectively. This treatment approach has also been shown to be very effective in HCV genotype 4 infections. However, it seems that this regimen does not provide a favorable SVR rate in genotype 1a infections.

Some studies have evaluated the combination of DCV with PEG-IFN lambda or alpha with RBV. These combinations have been mainly investigated in HCV genotype 1, 2, 3 and 4 infections, and the treatment duration was 12 to 48 weeks and differed between studies. In addition, some of these studies used ASV in combination with other drugs. The findings of our meta-analysis indicate that a 12-week SVR rate of 98% can be achieved in patients infected with genotype 4 with the PEG-IFN alpha/RBV/DCV/ASV regimen. This combination resulted in a 12-week SVR rate of 90.41% in TN patients with HCV genotype 1a infection. The treatment duration for these two regimens was 24 weeks. Moreover, these regimens include PEG-IFN, which is known to have certain side effects. As mentioned before, data on the combination of DCV and SMV (an inhibitor of the NS3/4A protein) are very limited, and this regimen has been used only in HCV genotype 1 infections. Moreover, this regimen has shown different 12-week SVR rates (from 50% to 95%) in TN, TE and LTX patients. Thus, combining VX-135, an inhibitor of NS5B polymerase, with DVV should be further investigated before it is used for HCV treatment.

Although all of these aforementioned regimens have considerably improved SVR rate compared with SOC treatment which was combination of PEG-IFN alpha/RBV however, BMS could not provide a same treatment approach with highest SVR rate and least treatment duration to be used in different GTs and conditions. Since there are treatment regimens associated with a 12-week SVR rate of more than 95%, we recommend that all other treatment approaches with an SVR rate below 90% be avoided. One of the regimens with an SVR rate of more than 95% is DCV/SOF. SOF, which is a product of Gilead, targets the NS5B polymerase and poses a high barrier against resistance. It is now used as the backbone for several interferon-free regimens (68, 69). The European medicine agency approved of combination therapy with DCV and SOF for the treatment of genotype 1 - 4 infections in 2014. Moreover, this treatment regimen was approved by the FDA first for genotype 3 infections in 2015 and then for genotype 1 infections in 2016 (70). As mentioned in the results section of this paper, patients with genotype 1 - 6 infections, including those with and without a history of previous treatment, with and without cirrhosis and liver and kidney transplantation, have been treated with this treatment approach. Further, in some settings, the use of RBV can also be helpful. However, it seems that adding RBV in some cases, such as genotype 3 infections, does not make a significant difference (71). Based on the available literature, it seems that until now, treatment with this regimen has focused on genotype 1 and 3 infections first and then other genotypes. Based on our results, HCV genotype 1 infections in patients without SLD can be treated using DCV/SOF for 12 or 24 weeks with and without RBV, as all these approaches resulted in a 12-week SVR rate of more than 95%. In genotype 1-infected patients with SLD, use of the DCV/SOF regimen for 24 weeks resulted in a 12-week SVR rate of 98%. Because of the limited data available about infection with other genotypes, we did not conduct a meta-analysis on studies that used this regimen on other genotypes. However, based on the data presented in Table 5, it seems that DCV/SOF has an acceptable SVR rate in cases of other genotype infections, especially genotype 3 and 4. A network meta-analysis that combined the data for HCV genotypes 1 and 4 evaluated the effect of DCV/SOF on TN and TE patients separately (53). In agreement with our results, they reported a 12-week SVR rate equal to or more than 95% for both groups with the DCV/SOF regimen. Therefore, DCV/SOF with and without RBV for a duration of 12 or 24 weeks can be considered as a highly useful treatment option in TN or TE patients with genotype 1 and 3 infections with and without cirrhosis. However, their effects on genotype other than 1 and 3 need to be more investigated.

In addition to the SVR rate, some other important factors, including the rate of serious adverse events (AEs), drug-drug interaction (DDI) and drug resistance, should be considered when selecting an appropriate treatment regimen under different conditions. The rate of serious AEs in genotype 1 and 4 infections treated with DCV/SOF has been reported to be 0.92% (96% CI = 0.00 - 2.49) and 3.22% (96% CI = 0.00 - 3.20) in TN and TE patients respectively. Furthermore, the rate of treatment discontinuation due to AEs in these patients was shown to be 0.05% (95% CI = 0.00 - 1.21) and 0.00 (95% CI = 0.00 - 2.25) respectively (53). As DCV can moderately inhibit organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 and P-glycoprotein transporter (P-GP), DDI between DCV and P-GP and OATP1B1 substrates is a possibility. Importantly, some drugs such as anti-convulsants (e.g., phenytoin and carbamazepine) and antimycobacterial agents (e.g., rifampin) can affect the serum DCV concentration (72, 73). With regard to the treatment of patients with HIV/HCV coinfection, DDI between DCV and efavirenz, nevirapine and ritonavir is possible (53). With regard to drug resistance, NS5A polymorphisms at amino acid positions M28, Q30, L31, and Y93 have been associated with resistance to DCV. Therefore, before initiation of therapy with DCV/SOF in HCV genotype 1a-infected patients with cirrhosis, screening for these polymorphisms should be performed (74). Till date, DCV has been approved for treatment of HCV genotype 1b infections in Japan (in combination with ASV), for treatment of genotypes 1 - 4 infections in Europe (in combination with SOF), and for treatment of genotypes 1 and 3 infections in the USA (in combination with SOF) (10).

In conclusion, we think that DCV is highly efficacious and safe for the treatment of patients with HCV infections under different conditions. Moreover, its ability to combine with other DAAs makes it a very good choice for HCV treatment.

References

-

1.

Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333-42. [PubMed ID: 23172780]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26141.

-

2.

Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(1):41-52. [PubMed ID: 11439948]. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200107053450107.

-

3.

de Martel C, Maucort-Boulch D, Plummer M, Franceschi S. World-wide relative contribution of hepatitis B and C viruses in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;62(4):1190-200. [PubMed ID: 26146815]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27969.

-

4.

Alavian SM, Haghbin H. Relative Importance of Hepatitis B and C Viruses in Hepatocellular Carcinoma in EMRO Countries and the Middle East: A Systematic Review. Hepat Mon. 2016;16(3):35106. [PubMed ID: 27226803]. https://doi.org/10.5812/hepatmon.35106.

-

5.

Razavi H, Elkhoury AC, Elbasha E, Estes C, Pasini K, Poynard T, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease burden and cost in the United States. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2164-70. [PubMed ID: 23280550]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26218.

-

6.

Sibley A, Han KH, Abourached A, Lesmana LA, Makara M, Jafri W, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus infections with today's treatment paradigm - volume 3. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22 Suppl 4:21-41. [PubMed ID: 26513446]. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12476.

-

7.

Edlin BR, Winkelstein ER. Can hepatitis C be eradicated in the United States? Antiviral Res. 2014;110:79-93. [PubMed ID: 25110202]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.015.

-

8.

Kamal-Yanni M. Hepatitis C drug affordability. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(2):73-4. [PubMed ID: 25617196]. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70365-1.

-

9.

Hesamizadeh K, Sharafi H, Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Behnava B, Alavian SM. Next Steps Toward Eradication of Hepatitis C in the Era of Direct Acting Antivirals. Hepat Mon. 2016;16(4). e37089.

-

10.

Manolakopoulos S, Zacharakis G, Zissis M, Giannakopoulos V. Safety and efficacy of daclatasvir in the management of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29(3):282-96. https://doi.org/10.20524/aog.2016.0041.

-

11.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-9.

-

12.

Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. [PubMed ID: 25810908]. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-72-39.

-

13.

Lok AS, Gardiner DF, Lawitz E, Martorell C, Everson GT, Ghalib R, et al. Preliminary study of two antiviral agents for hepatitis C genotype 1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):216-24. [PubMed ID: 22256805]. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1104430.

-

14.

Chayama K, Takahashi S, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ikeda K, Ishikawa H. Dual therapy with the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor, daclatasvir, and the nonstructural protein 3 protease inhibitor, asunaprevir, in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected null responders. Hepatol. 2012;55(3):742-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24724.

-

15.

Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, et al. Dual oral therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection and limited treatment options. J Hepatol. 2013;58(4):655-62. [PubMed ID: 23183526]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.037.

-

16.

Chayama K, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Kawakami Y. All-oral Combination of Daclatasvir Plus Asunaprevir in Interferon Ineligible Naive/Intolerant and Nonresponder Japanese Patients Chronically Infected with HCV Genotype 1b: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Hepatol. 2013;58:313.

-

17.

Lok AS, Gardiner DF, Hezode C, Lawitz EJ, Bourliere M, Everson GT, et al. Randomized trial of daclatasvir and asunaprevir with or without PegIFN/RBV for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 null responders. J Hepatol. 2014;60(3):490-9. [PubMed ID: 24444658]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.019.

-

18.

Manns M, Pol S, Jacobson IM, Marcellin P, Gordon SC, Peng CY, et al. All-oral daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: a multinational, phase 3, multicohort study. Lancet. 2014;384(9954):1597-605. [PubMed ID: 25078304]. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61059-X.

-

19.

Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, et al. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology. 2014;59(6):2083-91. [PubMed ID: 24604476]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27113.

-

20.

Kosaka K, Imamura M, Hayes CN, Abe H, Hiraga N, Yoshimi S. Emergence of resistant variants detected by ultra-deep sequencing after asunaprevir and daclatasvir combination therapy in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22(2):158-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12271.

-

21.

Iio E, Shimada N, Abe H, Atsukawa M, Yoshiza K, Takaguchi K. Efficacy of Daclatasvir/Asunaprevir According to Resistance Associated Variants in Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype1b. Hepatol. 2015;62:749-50.

-

22.

Akuta N, Sezaki H, Suzuki F, Kawamura Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M. Favorable efficacy of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir in treatment of elderly Japanese patients infected with HCV genotype 1b aged 70 and older. J Med Virol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24592.

-

23.

Kanda T, Yasui S, Nakamura M, Suzuki E, Arai M, Haga Y, et al. Daclatasvir plus Asunaprevir Treatment for Real-World HCV Genotype 1-Infected Patients in Japan. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13(6):418-23. [PubMed ID: 27279790]. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.15519.

-

24.

Kinugasa H, Ikeda F, Takaguchi K, Mori C, Matsubara T, Shiraha H, et al. Low frequency of drug-resistant virus did not affect the therapeutic efficacy in daclatasvir plus asunaprevir therapy in patients with chronic HCV genotype-1 infection. Antivir Ther. 2016;21(1):37-44. [PubMed ID: 26115551]. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP2976.

-

25.

Kumada H, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, et al. Randomized comparison of daclatasvir + asunaprevir versus telaprevir + peginterferon/ribavirin in Japanese hepatitis C virus patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(1):14-22. [PubMed ID: 26252875]. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13073.

-

26.

Miyazaki R, Miyagi K. Effect and Safety of Daclatasvir-Asunaprevir Combination Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1b -Infected Patients on Hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2016;21(10):1744-9987.

-

27.

Ogawa E, Furusyo N, Yamashita N, Kawano A, Takahashi K, Dohmen K, et al. Effectiveness and safety of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for HCV genotype 1b patients aged 75 and over with or without cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2016. [PubMed ID: 27142311]. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12738.

-

28.

Suda G, Kudo M, Nagasaka A, Furuya K, Yamamoto Y, Kobayashi T. Efficacy and safety of daclatasvir and asunaprevir combination therapy in chronic hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2016;14:14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-016-1162-8.

-

29.

Toyoda H, Kumada T, Tada T, Takaguchi K, Ishikawa T, Tsuji K. Safety and efficacy of dual direct-acting antiviral therapy (daclatasvir and asunaprevir) for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in patients on hemodialysis. J Gastroenterol. 2016;12:12.

-

30.

Wei L, Zhang M, Xu M, Chuang WL, Lu W, Xie W. A phase 3, open-label study of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection who are ineligible for or intolerant to interferon alfa therapies with or without ribavirin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;22(10):13379.

-

31.

Ikeda H, Watanabe T, Okuse C, Matsumoto N, Ishii T, Yamada N, et al. Impact of resistance-associated variant dominancy on treatment in patients with HCV genotype 1b receiving daclatasvir/asunaprevir. J Med Virol. 2016. [PubMed ID: 27329864]. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24608.

-

32.

Nam HC, Lee HL, Yang H, Song MJ. Efficacy and safety of daclatasvir and asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22(2):259-66. [PubMed ID: 27377910]. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2016.0020.

-

33.

Nagao Y, Kimura K, Kawahigashi Y, Sata M. Successful Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus-associated Oral Lichen Planus by Interferon-free Therapy with Direct-acting Antivirals. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7(7):179. [PubMed ID: 27388424]. https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2016.37.

-

34.

Everson GT, Sims KD, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hezode C, Lawitz E, Bourliere M, et al. Efficacy of an interferon- and ribavirin-free regimen of daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and BMS-791325 in treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):420-9. [PubMed ID: 24184132]. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.057.

-

35.

Poordad F, Sievert W, Mollison L, Bennett M, Tse E, Brau N, et al. Fixed-dose combination therapy with daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and beclabuvir for noncirrhotic patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. JAMA. 2015;313(17):1728-35. [PubMed ID: 25942723]. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3860.

-

36.

Hassanein T, Sims KD, Bennett M, Gitlin N, Lawitz E, Nguyen T, et al. A randomized trial of daclatasvir in combination with asunaprevir and beclabuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1204-6. [PubMed ID: 25559328]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.025.

-

37.

Muir AJ, Poordad F, Lalezari J, Everson G, Dore GJ, Herring R, et al. Daclatasvir in combination with asunaprevir and beclabuvir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection with compensated cirrhosis. JAMA. 2015;313(17):1736-44. [PubMed ID: 25942724]. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3868.

-

38.

Everson GT, Sims KD, Thuluvath PJ, Lawitz E, Hassanein T, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. Daclatasvir + asunaprevir + beclabuvir +/- ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1-infected treatment-naive patients. Liver Int. 2016;36(2):189-97. [PubMed ID: 26473667]. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12964.

-

39.

Pol S, Ghalib RH, Rustgi VK, Martorell C, Everson GT, Tatum HA. Daclatasvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C genotype-1 infection: a randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase 2a trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(9):671-7.

-

40.

Dore GJ, Lawitz E, Hezode C, Shafran SD, Ramji A, Tatum HA, et al. Daclatasvir plus peginterferon and ribavirin is noninferior to peginterferon and ribavirin alone, and reduces the duration of treatment for HCV genotype 2 or 3 infection. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(2):355-366 e1. [PubMed ID: 25311593]. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.007.

-

41.

Jensen D, Sherman KE, Hezode C, Pol S, Zeuzem S, de Ledinghen V, et al. Daclatasvir and asunaprevir plus peginterferon alfa and ribavirin in HCV genotype 1 or 4 non-responders. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):30-7. [PubMed ID: 25703086]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.018.

-

42.

Piroth L, Paniez H, Taburet AM, Vincent C, Rosenthal E, Lacombe K, et al. High Cure Rate With 24 Weeks of Daclatasvir-Based Quadruple Therapy in Treatment-Experienced, Null-Responder Patients With HIV/Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1/4 Coinfection: The ANRS HC30 QUADRIH Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):817-25. [PubMed ID: 25977266]. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ381.

-

43.

Hezode C, Alric L, Brown A, Hassanein T, Rizzetto M, Buti M. Randomized controlled trial of the NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for HCV genotype-4 (COMMAND-4). Antivir Ther. 2015;27(10).

-

44.

Jacobson I, Zeuzem S, Flisiak R, Knysz B, Lueth S, Zarebska-Michaluk D, et al. Daclatasvir vs telaprevir plus peginterferon alfa/ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 1. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(12):3418-31. [PubMed ID: 27022224]. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i12.3418.

-

45.

Flisiak R, Kawazoe S, Znoyko O, Assy N, Gadano A, Kao JH. Peginterferon Lambda-1a/Ribavirin with Daclatasvir or Peginterferon Alfa-2a/Ribavirin with Telaprevir for Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 1b. Int Soci Interferon Cytokine Res. 2016.

-

46.

Santagostino E, Pol S, Olveira A, Reesink HW, van Erpecum K, Bogomolov P, et al. Daclatasvir/peginterferon lambda-1a/ribavirin in patients with chronic HCV infection and haemophilia who are treatment naive or prior relapsers to peginterferon alfa-2a/ribavirin. Haemophilia. 2016. [PubMed ID: 27339614]. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12947.

-

47.

Hezode C, Hirschfield GM, Ghesquiere W, Sievert W, Rodriguez-Torres M, Shafran SD, et al. Daclatasvir plus peginterferon alfa and ribavirin for treatment-naive chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 or 4 infection: a randomised study. Gut. 2015;64(6):948-56. [PubMed ID: 25080450]. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307498.

-

48.

Izumi N, Yokosuka O, Kawada N, Osaki Y, Yamamoto K, Sata M, et al. Daclatasvir combined with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in Japanese patients infected with hepatitis C genotype 1. Antivir Ther. 2014;19(5):501-10. [PubMed ID: 24451151]. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP2731.

-

49.

Fontana RJ, Brown RS, Moreno-Zamora A, Prieto M, Joshi S, Londono MC. Daclatasvir combined with sofosbuvir or simeprevir in liver transplant recipients with severe recurrent hepatitis C infection. Liver Transpl. 2016;22(4):446-58. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.24416.

-

50.

Zeuzem S, Hezode C, Bronowicki JP, Loustaud-Ratti V, Gea F, Buti M, et al. Daclatasvir plus simeprevir with or without ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. J Hepatol. 2016;64(2):292-300. [PubMed ID: 26453968]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.09.024.

-

51.

Beinhardt S, Al Zoairy R, Ferenci P, Kozbial K, Freissmuth C, Stern R. DAA-based antiviral treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C in the pre- and post kidney transplantation setting. Transpl Int. 2016;20(10):12799.

-

52.

Gane E, Stedman C, Garg V, George S, Kieffer T, Krop J. An interferon- and ribavirin-free 12-week regimen of once-daily vx-135 and daclatasvir in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hcv infection. J Hepatol. 2014;60(1):528-9.

-

53.

Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Guidelines for the Screening Care and Treatment of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis C Infection: Updated Version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

-

54.

Sulkowski MS, Gardiner DF, Rodriguez-Torres M, Reddy KR, Hassanein T, Jacobson I, et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(3):211-21. [PubMed ID: 24428467]. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306218.

-

55.

Pol S, Bourliere M, Lucier S, De Ledinghen V, Zoulim F, Dorival-Mouly C. LO3 : Safety and efficacy of the combination daclatasvir-sofosbuvir in HCV genotype 1-mono-infected patients from the french observational cohort ANRS CO22 hepather. J Hepatol. 2015;62:258-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8278(15)30149-5.

-

56.

Wyles DL, Ruane PJ, Sulkowski MS, Dieterich D, Luetkemeyer A, Morgan TR, et al. Daclatasvir plus Sofosbuvir for HCV in Patients Coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):714-25. [PubMed ID: 26196502]. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1503153.

-

57.

Foster GR, Irving WL, Cheung MC, Walker AJ, Hudson BE, Verma S, et al. Impact of direct acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1224-31. [PubMed ID: 26829205]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.029.

-

58.

Poordad F, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Landis C, Fontana RJ, Yang R, et al. Daclatasvir with sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C virus infection with advanced cirrhosis or post-liver transplantation recurrence. Hepatology. 2016;63(5):1493-505. [PubMed ID: 26754432]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28446.

-

59.

Welzel TM, Herzer K, Ferenci P, Petersen J, Gschwantler M, Cornberg M. P0772 : Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin for the treatment of HCV in patients with severe liver disease: Interim results of a multicenter compassionate use program. J Hepatol.

-

60.

Rockstroh JK, Welzel TM, Ingiliz P, Petersen J, van der Valk M, Herzer K. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin for the treatment of chronic HCV in patients coinfected with HIV: Interim results of a multicenter compassionate use program. Hepatol. 2015;623:728-9.

-

61.

Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, et al. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature. 2010;465(7294):96-100. [PubMed ID: 20410884]. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08960.

-

62.

Targett-Adams P, Graham EJ, Middleton J, Palmer A, Shaw SM, Lavender H, et al. Small molecules targeting hepatitis C virus-encoded NS5A cause subcellular redistribution of their target: insights into compound modes of action. J Virol. 2011;85(13):6353-68. [PubMed ID: 21507963]. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00215-11.

-

63.

Asselah T. NS5A inhibitors: a new breakthrough for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2011;54(5):1069-72. [PubMed ID: 21167889]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.033.

-

64.

Garimella T, Wang R, Luo WL, Hwang C, Sherman D, Kandoussi H, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of daclatasvir in subjects with renal function impairment. Antivir Ther. 2015;20(5):535-43. [PubMed ID: 25654812]. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP2941.

-

65.

Smolders EJ, de Kanter CT, van Hoek B, Arends JE, Drenth JP, Burger DM. Pharmacokinetics, Efficacy, and Safety of Hepatitis C Virus Drugs in Patients with Liver and/or Renal Impairment. Drug Saf. 2016;39(7):589-611. [PubMed ID: 27098247]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0420-2.

-

66.

McPhee F, Sheaffer AK, Friborg J, Hernandez D, Falk P, Zhai G, et al. Preclinical Profile and Characterization of the Hepatitis C Virus NS3 Protease Inhibitor Asunaprevir (BMS-650032). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(10):5387-96. [PubMed ID: 22869577]. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01186-12.

-

67.

Pelosi LA, Voss S, Liu M, Gao M, Lemm JA. Effect on hepatitis C virus replication of combinations of direct-acting antivirals, including NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(10):5230-9. [PubMed ID: 22850513]. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01209-12.

-

68.

Bourliere M, Oules V, Ansaldi C, Adhoute X, Castellani P. Sofosbuvir as backbone of interferon free treatments. Digest Liver Dis. 2014;46:212-20.

-

69.

Alavian SM. Sofosbuvir has come out of the magic box. Hepat Mon. 2013;13(12):16916. [PubMed ID: 24358046]. https://doi.org/10.5812/hepatmon.16916.

-

70.

Alavian SM, Hajarizadeh B, Lankarani KB, Sharafi H, et al. Recommendations for the clinical management of hepatitis C in Iran: A consensus-based national guideline. Hepat Mon. 2016;16(8). e40959. https://doi.org/10.5812/hepatmon.guideline.

-

71.

Ampuero J, Reddy KR, Romero-Gomez M. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3: Meta-analysis on sustained virologic response rates with currently available treatment options. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(22):5285-92.

-

72.

Tischer S, Fontana RJ. Drug-drug interactions with oral anti-HCV agents and idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity in the liver transplant setting. J Hepatol. 2014;60(4):872-84. [PubMed ID: 24280292]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.013.

-

73.

Summary of product characteristics. 2016. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003768/WC500172848.pdf.

-

74.

Highlights of prescribing information. 2016. Available from: http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_daklinza.pdf.

-

75.

Nelson DR, Cooper JN, Lalezari JP, Lawitz E, Pockros PJ, Gitlin N, et al. All-oral 12-week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY-3 phase III study. Hepatology. 2015;61(4):1127-35. [PubMed ID: 25614962]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27726.

-

76.

Leroy V, Angus P, Bronowicki JP, Dore GJ, Hezode C, Pianko S, et al. Daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 3 and advanced liver disease: A randomized phase III study (ALLY-3+). Hepatology. 2016;63(5):1430-41. [PubMed ID: 26822022]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28473.

-

77.

Mangia A, Arleo A, Copetti M, Miscio M, Piazzolla V, Santoro R. The combination of daclatasvir and sofosbuvir for curing genotype 2 patients who cannot tolerate ribavirin. Liver Int. 2016;36(7):971-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13069.

-

78.

Ji D, Chen GF, Wang C, Wang YD, Shao Q, Li B, et al. Twelve-week ribavirin-free direct-acting antivirals for treatment-experienced Chinese with HCV genotype 1b infection including cirrhotic patients. Hepatol Int. 2016. [PubMed ID: 27443347]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-016-9755-0.

-

79.

Hézode C, Abergel A, Chas J, Conti F, Cotte L, Tateo M. Sat-131 sustained virologic response to daclatasvir and sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, among patients in the french daclatasvir atu programme infected with hcv genotypes 4, 5 and 6. J Hepatol. 2015;62:755.

-

80.

Mandorfer M, Schwabl P, Steiner S, Scheiner B, Chromy D, Bucsics T. Interferon-free treatment with sofosbuvir/daclatasvir achieves sustained virologic response in 100% of HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients with advanced liver disease. AIDS. 2016;30(7):1039-47.

-

81.

Herzer K, Welzel TM, Ferenci P, Petersen J, Gschwantler M, Cornberg M. Daclatasvir in combination with sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin is safe and efficacious in liver transplant recipients with HCV recurrence: Interim results of a multicenter compassionate use program. Hepatol. 2015;62:341.

-

82.

Coilly A, Fougerou-Leurent C, de Ledinghen V, Houssel-Debry P, Duvoux C, Di Martino V. Multicentre experience using daclatasvir and sofosbuvir to treat hepatitis C recurrence after liver transplantation -The CO23 ANRS CUPILT study. J Hepatol. 2016;1(16):30253-7.