Fulltext

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a serious global public health issue and the 10th leading cause of mortality, worldwide, with more than 1 million annual deaths (1, 2). Infection with HBV can be diagnosed either after developing hepatitis-related symptoms or following routine blood testing. During the acute phase of infection, IgM antibodies against the Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) predominate. As infection evolves, IgM anti-HBc declines in titer, while IgG anti-HBc can persist for many years (3, 4). Accordingly, anti-HBc is considered as a major serological marker for HBV infection (5). Positivity for both anti-HBc and HBsAg (Hepatitis B surface antigen) indicates ongoing infection (6), while antibody response against HBsAg (anti-HBs) appears only during the late phase of infection (6). Screening for serum HBsAg is widely used as a major test for HBV infection. Although HBsAg disappearance was long considered as an indication of HBV clearance and infection elimination, nowadays, it is well established that HBsAg might not be detected in the serum of even infected patients (7). This can be explained by either infection chronicity where HBsAg levels are maintained below the detection limit or relative HBsAg synthesis downregulation (8, 9). Noteworthy, some HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive individuals, as in the case of OBI (occult hepatitis B infection), are characterized by continuous HBV replication (10, 11), indicating that the absence of HBsAg in blood of putatively healthy individuals could not serve as a marker for the absence of circulating HBV. Moreover, as anti-HBc can persist for many years, even after total recovery of the patient, anti-HBc screening test, being implemented in some countries such as Lebanon, in order to decrease the risk of post-blood transfusion HBV infection, might give false positive results regarding the actual state of the individual and thus, leading to high discard rate of blood units.

Aiming at identifying an easy and reliable strategy that would enable the specification of blood safety, we evaluated, in this study, the prevalence of HBV-DNA in correlation with the presence of anti-HBc and anti-HBs in Lebanese blood donors. Our results identified the absence of HBV-DNA in all donors which are simultaneously positive for anti-HBc and anti-HBs antibodies. Our data indicate that screening anti-HBc positive samples for anti-HBs is highly beneficial for determining blood safety and avoiding loss of precious blood samples during blood transfusion.

In order to ensure the blood supply as safe as possible, all donors were screened to meet certain eligibility criteria where the donor must be at least 17 years old, with a pulse of 50 - 100 beats per minute (no abnormalities), body temperature of ≤ 37.5ºC (orally), body weight of > 50 Kg, hemoglobin level of ≥ 12.5 g/dL, hematocrit of ≥ 38%, and blood Pressure of: ≤ 180 mm Hg systolic and ≤ 100 mmHg diastolic. Moreover, infectious disease screening tests for HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HCV (Hepatitis C virus), HIV-1 (Human immunodeficiency virus-1), and HIV-2 antibodies as well as Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) serological test for syphilis were carried out for each donor. The donors were also screened for disease risk factors using a health history questionnaire where they were asked specific questions regarding lifestyle, health, medical, and travel history.

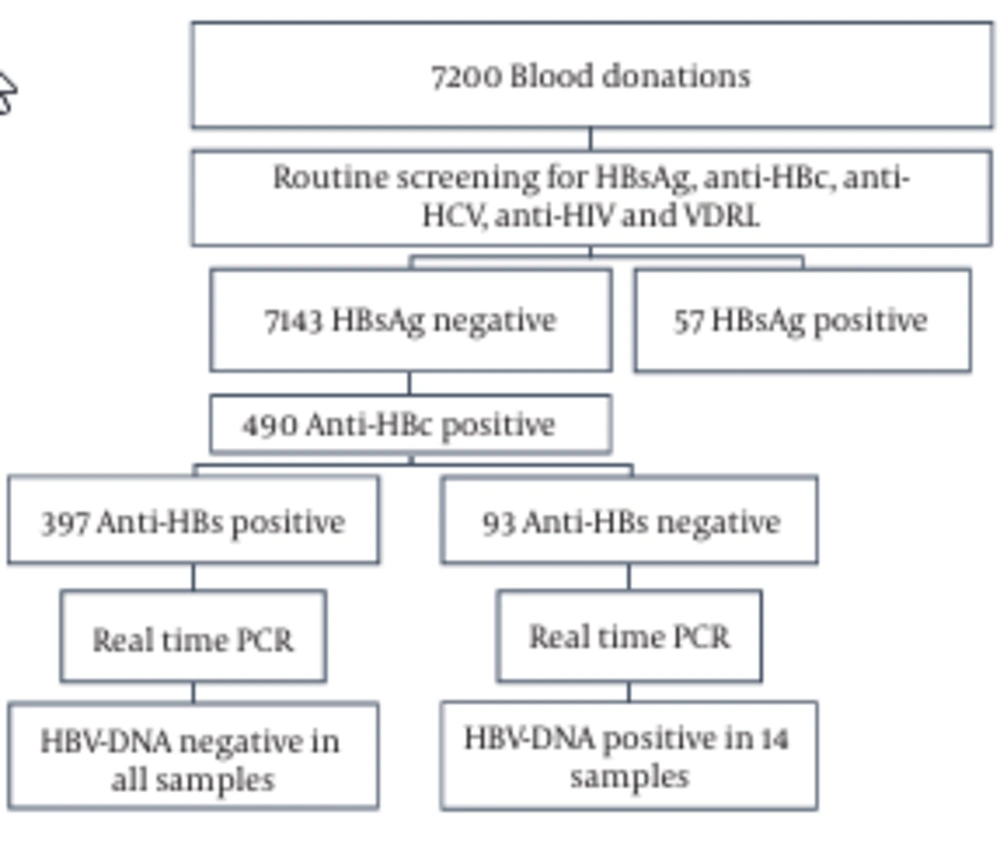

During the time frame of this study (2015), 7200 blood samples from voluntary anti-HCV- and anti-HIV-negative blood donors in three different Lebanese governorates (Mount Lebanon, South, and Beirut) were evaluated for HBsAg. The number of patients participating from each of the mentioned governorates was 1320, 3400, and 2480, respectively. HBsAg-positive donors were excluded and HBsAg-negative donors were considered for inclusion in this study. Samples that were found to be anti-HBc positive were further tested for anti-HBc IgM, anti-HBs, and HBV-DNA.

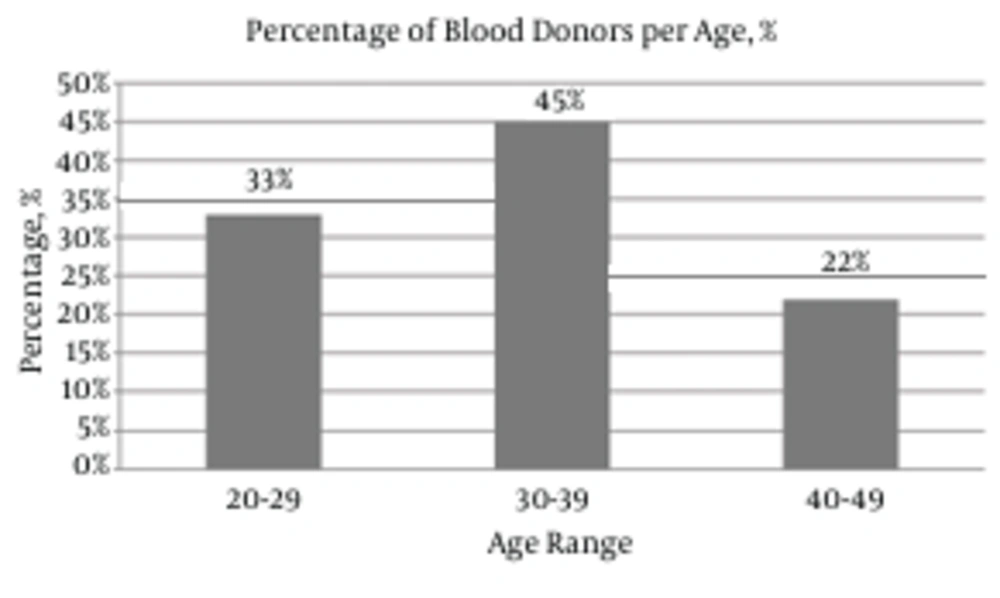

A total of 7200 blood samples were collected from volunteer donors. 33%, 45%, and 22% of the donors were in the age range of 20 - 29, 30 - 39, and 40 - 49 years, respectively (Figure 1). 98% of the donors were male, 2% were female, 95% were first-time donors, and 5% were regular donors. The samples were screened for HBsAg and anti-HBc (Figure 2). In total, 99.2% (7143/7200) were HBsAg-negative, while the remaining 0.8% (57/7200) samples were HBsAg-positive (Figure 2). In the second step, the HBsAg-negative samples were screened for the presence of anti-HBc. The anti-HBc positivity rate was 6.8% (490/7143) (Figure 2). It is noteworthy that all the anti-HBc positive samples were negative for anti-HBc IgM (Table 1), and thus suspected to have OBIs. The anti-HBc positive samples were then screened for anti-HBs positivity/negativity as well as for the presence/absence of HBV-DNA. Among the tested samples, 81% (397/490) were positive for anti-HBs and they were all negative for HBV-DNA (Figure 2 and Table 1). On the other hand, the remaining 19% (93/490) were negative for anti-HBs, whereas HBV-DNA appeared to be positive in 2.85% (14/93) of this population (viral load range: 100 to 300 IU/ml) (Figure 2 and Table 1). In general, these observations demonstrate a direct correlation between the absence of HBV-DNA and the simultaneous presence of anti-HBc and anti-HBs antibodies.

| Prevalence |

|---|

| Anti- HBs |

| 397 (81) positive |

| 93 (19) negative |

| Anti- HBc IgM |

| 397 (81) negative |

| 93 (19) negative |

| HBV-DNA |

| 397 (81) negative |

| 14 (2.85) positive |

Ensuring blood safety is a global issue since blood transfusion serves as a vital therapy for managing different medical and surgical conditions where a huge number of lives can be rescued following blood administration. Despite that, blood transfusion might represent a major risk factor for the transmission of different infectious agents among which is the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Following HBV infection, antibody responses to different HBV proteins, including anti-HBc and anti-HBs, are detected in human sera (12). Following clearance of transient HBV infection, anti-HBc level remains high for longer periods than other HBV markers, thus serving as a universal indicator for HBV infection (13). The “anti-HBc” serological status could be attributed to different parameters among which are: (a) passive transfer of anti-HBc; (b) a recent HBV infection during which HBsAg has disappeared, while anti-HBs levels are yet undetectable; or (c) chronic HBV infection during which HBsAg is undetectable due to very low viraemia, a clinical phase recognized as occult HBV infection (14-17). Although many countries implement an anti-HBc test before blood transfusion, in an attempt to decrease the risk of HBV transmission, recent studies (18-20) clearly demonstrated an absence of correlation between anti-HBc positivity and presence of HBV-DNA, indicating that anti-HBc screening is not a recommended method to identify HBV infection. For instance, a donor showing positivity for anti-HBc may be a naïve-HBV carrier i.e. a person with a past history of HBV infection or a carrier of non-detectable levels of HBsAg (14, 17, 21-24). The false positive indications obtained in anti-HBc test can lead to discard of large quantities of blood units as well as losing precious blood samples especially those issued from donors exhibiting rare blood types. More recently, triplex nucleic acid tests (NATs) have been implemented in many countries, including the United States and China, during blood screening for infectious agents such as HBV, HCV, and HIV. A major benefit of HBV NAT is the detection of OBI. Moreover, it has been shown that NAT and serological analysis are complementary during detection of HBV in first-time donors, while NAT is more beneficial in the case of repeat donors (25). Alternatively, this method is challenged by the different sensitivities of the existing commercial NAT assay systems (26-28). Nowadays, different approaches can be conceived to reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted HBV. These vary depending on different parameters including: the socioeconomic situation in a certain country, the prevalence of HBV, and the availability of certain technical services. Hence, different algorithms can be followed, such as a sole serological screening for HBsAg, a test for both HBsAg and anti-HBc, NAT approach, or a combination of serology and NAT. The aim of the present work was to describe a new strategy that ensures blood safety and resolves the problem of false positive results obtained during anti-HBc screen method. During this study, the observed HBsAg-positivity rate (0.8%) was comparable to that identified previously in Lebanese population (0.98% in 1998; 0.75% in 1999; 0.78% in 2000; 0.77% in 2001; 0.66% in 2002, and 0.6% in 2003) (21). The major output of this study was that HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive blood samples, identified among 7200 tested samples, were classified into 2 categories. The first category included anti-HBc positive samples that were positive for anti-HBs. All Samples belonging to this category were negative for HBV-DNA. The second category was composed of anti-HBc positive samples that were negative for anti-HBs. Some of those samples were positive for HBV-DNA whilst others were negative. Interestingly, our observations indicated the association of the absence of HBV-DNA with the simultaneous presence of both anti-HBc and anti-HBs. Of great importance, our data indicates that a double anti-HBc and anti-HBs test would be beneficial to ensure blood safety and avoid loss of blood units. For instance, instead of directly discarding a blood sample showing positivity for anti-HBc, an additional screen for anti-HBs positivity will lead to keeping this sample. Hence, our proposed diagnosis strategy will be highly beneficial at both medical and socioeconomic levels.