Abstract

Background:

Pubertal development and sexuality in prime adolescence can individually or both affect academic performance during the secondary cycle.Objectives:

The present study aims to examine the relationship between pubertal maturation, sexuality and academic Performance of secondary school students.Methods:

Data were collected via a cross-sectional survey after the release of the first quarter results. The sample was composed of 418 students (195 boys and 223 girls aged 13.96 ± 0.97 and 14.26 ± 0.85 years old respectively). The pubertal development scale and sexuality at prime adolescence scales were used to collect data. Academic performance was assessed based on quarterly cumulative GPA. Chi-square and Pearson's correlation tests were used and responses were structured into subcategories regarding factors of pubertal development, sexuality and academic performance.Results:

The pubertal development of girls was more advanced than that of boys; the boys scores on the "going out with someone" scale (P ≤ 0.05) and on the “flirting with the aim of having sexual relations” scale (P ≤ 0.01) whereas girls scores on the "giving priority to love" scale (P ≤ 0.05). In general academic performance was above mean and below mean respectively for boys and girls. Pubertal development and sexuality were negatively correlated with academic performance mostly in girls.Conclusions:

The developmental stage was more pronounced in girls. Boys were ahead in sexuality and the mean of their academic performance was higher. The interactions of development and sexuality and their combined effect negatively influenced the academic performance of girls and boys with gender-specific degrees.Keywords

1. Background

Aristotle stated in “historia animalium” that menarche occurred when a girl was “twice 7 years old”, an age much younger than that found in the last centuries of recorded history (1). However, over the past 150 years, we have witnessed a drop in the age of menarche in the range of 1 to 4 months per decade in the world in general and in industrialized countries in particular (2). The mechanisms controlling the onset of puberty at a younger age and the pace of development are complicated (3). According to some authors, this most important bio-social transition in human development is not only the result of the improvement in the socio- economic and health situation of populations, but the interactions of genetic, racial, nutritional and environmental factors (3, 4).

Puberty is an essential and complex process with great physiological and maturation variations (5). It is a universal experience of normal human development, marking the transition from childhood to adulthood and is accompanied by physical growth, brain maturation and sexual maturation leading to reproductive capacity (5). Nowadays, an increasing number of countries are experiencing an earlier development of secondary sex characteristics in children (6, 7). However, this earlier puberty is associated with a higher risk of psychological problems, cancers of the breasts and the reproductive system (8). A recent data suggest that adolescents with the earliest pubertal maturation had an earlier breast development (2). This behavior combine with their quest for autonomy, their decision- making without referring to parental authority, their affirmation of individuality and their particularities, can led to an earlier active genital life and undoubtedly explain their decline in academic performance.

A survey of recent work carried out shows that many studies on the relationship between pubertal maturation, sexuality and academic performance have been undertaken in the Maghreb and in the West and southern of Africa (9-11). However, few studies have been undertaken in the Republic of Congo and the results obtained from the above mentioned African area cannot be transposed to our society to explain the link between these three factors. This brings us to the following question: What is the influence of both pubertal maturation and sexuality on the academic performance of Ngamaba Tsalakoua’s students? This study attempts to understand how early maturation exposes the student to early sexuality and therefore negatively influences his academic Performance. Its interest consists of evaluating the pubertal maturation and sexuality in order to understand their impact on the academic performance among early adolescents in the Republic of Congo. This could then serve to competent authorities of the Ministry of Preschool, Primary, Secondary Education and Literacy (MEPPSA) to put in place strategies to improve the academic performance of their learners.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to examine the relationship between pubertal maturation, sexuality and academic performance of secondary school students.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample

A cross sectional study with a total of 418 secondary school students (195 boys and 223 girls) aged 13.96 ± 0.97 and 14.26 ± 0.85 years respectively were recruited from the general education middle school named Ngamaba Tsalakoua. It is located in the seventh district of the capital Brazzaville. By using a stratified cluster random sampling method, each grade level retained constituted a cluster and the formula n = z2 xp (pq)/m2 was applied to extract from each cluster a sub- sample as reported by Sales-Wuillemin (12). In the end, 106 from the 7th grade, 185 from the 8th grade and 127 from the 9th grade were added to obtain the sample of 418 pupils.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included: Being registered in Ngamaba Tsalakoua for the current year; be aged 12 to 15 years; voluntarily agree to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included being in 10th grade.

3.3. Assessment of Sexuality in Prime Adolescence

To assess the sexuality in prime adolescence, the sexuality in prime adolescence scale (12 to 15 years old) developed in 1998 by Courtois et al. was used (13). On this issue, participants completed the questionnaire as reported by Potard et al. (14). It is composed of 15 items evaluates 3 significant dimensions of sexuality in early adolescence: "Going out with someone”; “privilege love” and “Dredge hoping to have intimate relationships”. It is a self-assessment scale with true-false answers.

3.4. Assessment of Pubertal Development

To assess the pubertal development, the pubertal development scale (PDS) developed in 1988 by Petersen et al. was used. Pubertal development scale has a good reliability and several studies indicated that its scores are related to physical exam and hormone levels (15-17). On this issue, participants completed the PDS as reported by Koopman-Verhoeff et al. (18), this self-questionnaire is composed of 5 items concerning the progress of body changes: Height growth, body hair (pubic and armpits), skin changes (including the appearance of pimples), voice becoming deeper and facial hair (beard) for boys; breast development and onset of menstruation for girls. These different indices are taken into account for the evaluation of the pubertal stage divided into 5 stages: Pre puberty, precocious puberty, average puberty, end of puberty and post puberty (adult).

3.5. Socio Demographic Profile

The socio demographic variables consisted of the age (12, 13, 14 and 15 years), gender (boy and girl) and education level (7th; 8th and 9th grades).

3.6. Data Analysis

Data collected were analyzed using SPSS software version 25 (statistical package for the social sciences). Qualitative variables were processed using descriptive statistics and the results were expressed as frequency and percentage. To examine the association between student variables, we used Pearson's chi-square test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

The girls were mostly old in the three age groups while the boys were only for age 15 (Table 1). Furthermore, there were more girls in 7th and 9th grades compared to boys students, while boys were in the 8th grade (Table 2).

| Years | Gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | |

| 12 | 21 (9.4) | 6 (3.1) |

| 13 | 46 (20.6) | 35 (17.9) |

| 14 | 76 (34.1) | 57 (29.2) |

| 15 | 80 (35.9) | 97 (49.7) |

| 13.96 ± 0.97 | 14.26 ± 0.85 | |

| Grad | Gender | Academic Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| 7th | 64 (28.7) | 42 (21.5) | 10.36 ± 3.6 | 9.44 ± 3.7 |

| 8th | 86 (38.6) | 99 (50.8) | 9.04 ± 2.7 | 9.43 ± 3.0 |

| 9th | 73 (32.7) | 54 (27.7) | 9.29 ± 1.6 | 9.57 ± 0.9 |

| Total | 223 (100) | 195 (100) | 10.12 ± 1.6 | 10.20 ± 1.4 |

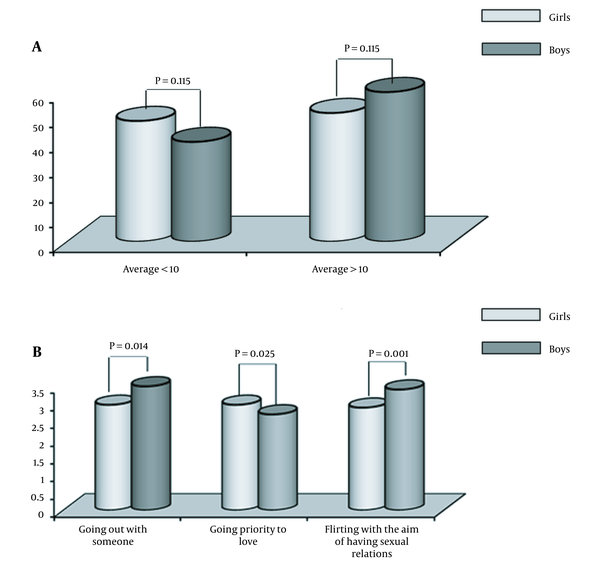

Girls were more likely to score below average while boys were significantly scored above average (Figure 1A). Whereas, boys had significantly higher scores on the “going out with someone” scale (3.49 ± 1.81 vs 2.97 ± 2.01; t = 2.51, P < 0.05) and on the “flirting with the aim of having sexual relations” scale (3.40 ± 1.46 vs 2.88 ± 1.43; t = 3.33, P < 0.01) respectively (Figure 1B).

A, distribution of the quarterly average by gender; B, comparison of sexuality scores by gender

The average score for each of the pubertal characteristics increases with age for boys and girls. It appears that the pubertal development of girls is more advanced than that of boys in each of these three evaluations. Additionally, there is a sequence in the onset of pubertal features. For the majority of boys, the growth of pubic hair and increase in height occur before other pubertal changes, while the growth of facial hair develops last. However, for the majority of girls, changes in breast growth occurs before onset of menstruation, growth of body hair and waistline, while change in skin occurs after (Table 3).

| Quest a | 7th Grade | 8th Grade | 9th Grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| Q1 | 2.53 ± 0.53 | 2.65 ± 0.48 | 3.10 ± 0.84 | 3.12 ± 0.87 | 3.67 ± 0.47 | 2.37 ± 0.68 |

| Q2 | 2.06 ± 0.68 | 2.53 ± 0.63 | 2.33 ± 0.80 | 2.63 ± 0.89 | 2.73 ± 0.90 | 2.85 ± 0.78 |

| Q3 | 1.59 ± 0.72 | 1.81 ± 0.76 | 1.84 ± 0.59 | 1.89 ± 0.81 | 2.01 ± 0.79 | 2.28 ± 0.83 |

| Q4F | 2.45 ± 0.66 | - | 3.08 ± 0.93 | - | 3.66 ± 0.71 | - |

| Q5F b | 2.41 ± 1.50 | - | 2.99 ± 1.42 | - | 3.59 ± 1.03 | - |

| Q4G | - | 1.84 ± 0.65 | - | 1.96 ± 0.96 | - | 2.22 ± 0.81 |

| Q5G | - | 1.72 ± 0.66 | - | 1.38 ± 0.73 | - | 1.54 ± 0.69 |

| 2.03 ± 0.53 | 1.93 ± 0.35 | 2.37 ± 0.48 | 2.02 ± 0.52 | 2.65 ± 0.49 | 2.25 ± 0.49 | |

From one evaluation to another, the distribution of the different pubertal statuses shifts towards a status characterizing a higher level of development. In addition, the pubertal development of girls outstrips the boy’s one precisely for the 7th grade (46.9 % vs 19.0 %) see Table 4.

| Status | 7th Grade | 8th Grade | 9th Grade | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n = 64) | Boys (n = 42) | Girls (n = 86) | Boys (n = 99) | Girls (n = 73) | Boys (n = 54) | Girls | Boys | |

| Pre-puberty | 46.9 | 19.0 | 19.8 | 34.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 24.7 | 24.6 |

| Onset of puberty | 31.3 | 54.8 | 33.7 | 39.4 | 24.7 | 37.0 | 30.0 | 42.1 |

| Intermediate puberty | 20.3 | 26.2 | 37.2 | 24.2 | 47.9 | 40.7 | 35.9 | 29.2 |

| Advanced puberty | 1.5 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 2.1 | 16.4 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 4.1 |

| Completed puberty | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Pubertal development was not correlated with the scales “going out with someone” and “flirting with the aim of having sexual relations”. It was also negatively correlated with academic performance in girls. Moreover, academic performance were significantly correlated with the scales “going out with someone” and “giving priority to love” in girls only (Table 5).

| Pubertal Development Score | Academic Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| Going out with someone | Ns | Ns | -0.23 *** | Ns |

| Giving priority to love | Ns | -0.15 * | -0.19 ** | Ns |

| Flirting with the aim of having sexual relations | Ns | Ns | -0.06 | Ns |

| Academic performance | -0.14 * | Ns | ||

5. Discussion

This study completes those demonstrating the links between pubertal development and sexuality and between sexuality and academic performance. We try to show that the development appears, on the basis of statistical analyses, to be associated with sexuality and academic performance. Furthermore, sexuality also appears to be associated with low academic performance.

5.1. Relationship Between Pubertal Maturation and Sexuality in Prime Adolescence

Pubertal development and the onset of puberty explain differences in the establishment of sexuality in adolescents. The result from Table 5 unexpectedly showed that the level of pubertal development is not corralled to the components of sexuality. In line with previous study (18), the components of sexuality such as "going out with someone", "prioritizing love" and "flirting in the hope of having intimate relations" do not appear to be influenced by pubertal development especially in girls. This can be explained by the less “behavioral” and essentially sentimental content in this scale. Moreover, this can also be explained by the indirect effects on pubertal development, namely physical, environmental and cultural (19, 20). Indeed, these physical or environmental transformations for the subject and for those around him modify his behavior, his representations of himself, his attitudes, the way looks at him and the expectations regarding him.

The result of the present study shows a significant difference between the scale of pubertal development and certain components of the scale of sexuality. Indeed, pubertal development and the onset of puberty explain the differences in the establishment of sexuality at this age. The results show that the “going out with someone” and “flirting with the aim of having sexual relations” scales are globally related to the level of pubertal development. This reflects the fact that the physiological transformations of puberty arouse in adolescents a certain sexual curiosity to then become sexually active. In addition, we observed a link between pubertal maturation and a component of sexuality “giving priority to love” in boys. This result can be explained by the integration of the gendered body, the affirmation of sexual identity, the need to manage genital urges differently, the appearance of new interests and behaviors in the sexual field in boys compared to at the girl.

5.2. Relationship Between Pubertal Development and Academic Performance

We observed that pubertal development was negatively correlated with academic performance in girls. Accordingly, a previous study showed negative and significant correlations between pubertal development and academic performance in girls. One study reported a negative association between pubertal development and academic performance in girls at age 12 and especially at age 16 (3). Similarly, an empirical study stated that, early menarche was shown to be associated with low educational attainment (4). On the one hand, the negative correlation between pubertal development and academic performance can be explained by a rapid life history, where sexual reproduction becomes possible at an earlier stage, rather than at maturity. Moreover, this result can also be explained by the influence of environmental factors. On this subject, it has been shown that, menarche can be triggered by stressful environments, which are detrimental to academic success (10, 19). On the other hand, this negative correlation observed can be explained by the precarious health of the girls in our sample. This statement seems to be in agreement with previous studies which have shown that educational attainment was strongly associated with health in that development early puberty predicting poor health was associated with negative academic performance (3, 21). In addition, we observed an absence of correlation between pubertal development and academic performance in boys. Contrary to the result of the present study, previous studies have shown negative and significant correlations between pubertal development and academic performance in boys. The lack of correlation can be explained by the fact that the questionnaire on pubertal development is subject to strong subjectivity (3).

5.3. Relationship Between Sexuality and Academic Performance

We observed that academic performance were negatively correlated with the components of the sexuality scale “going out with someone”, “giving priority to love” and “flirting with the aim of having sexual relations” in girls only. However, only the first two components were significantly correlated. This result confirms those of previous studies like a longitudinal study (22) and cross-sectional studies (10). Indeed, early sexual debut within a secondary school of Ngamaba Tsalakoua negatively influenced academic performance among girls. The early sexual debut constitutes a risk factors predicted poor academic performance. As stated by Lanari et al. (9), a negative relationship between sexual activity and academic performance refers to supporting the idea that health consequences and adolescent sexual activity education merit public policy efforts.

5.4. Limitation of the Study

The limitations described in the work of the peers are also valid for the present study. Some limitations should be considered in the assessment of the results. The first is related to the small size of our sample (n = 418). The second limitation relates to the nature of the studies based on respondents' declarations, and on their ability to speak frankly about sexuality. Among the strengths, this study holds a special place here, and other data available to us attest to its great importance in the representation that adolescents have of pubertal development, of sexuality in prime adolescence and of their dropping academic performance.

5.5. Conclusions

The results showed unexpectedly that the pubertal development was not related to the components of sexuality among girls while it was negatively correlated with their academic performance. However, the pubertal development was negatively correlated with the components of the sexuality scale “giving priority to love” among boys but wasn’t associated with their academic performance.

References

-

1.

Lee Y, Styne D. Influences on the onset and tempo of puberty in human beings and implications for adolescent psychological development. Horm Behav. 2013;64(2):250-61. [PubMed ID: 23998669]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.03.014.

-

2.

Mazzarino J. [Update on pubertal development: observational feasibility pilot study] [thesis]. Bordeaux: University of Bordeaux; 2018. French.

-

3.

Torvik FA, Flato M, McAdams TA, Colman I, Silventoinen K, Stoltenberg C. Early Puberty Is Associated With Higher Academic Achievement in Boys and Girls and Partially Explains Academic Sex Differences. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(3):503-10. [PubMed ID: 33795203]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.02.001.

-

4.

Gill D, Del Greco MF, Rawson TM, Sivakumaran P, Brown A, Sheehan NA, et al. Age at Menarche and Time Spent in Education: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Behav Genet. 2017;47(5):480-5. [PubMed ID: 28785901]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC5574970]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-017-9862-2.

-

5.

Marceau K, Hottle S, Yatcilla JK. Puberty in the Last 25 Years: A Retrospective Bibliometric Analysis. J Res Adolesc. 2019;29(1):96-114. [PubMed ID: 30869844]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC6868528]. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12396.

-

6.

Pang B, Wang Q, Yang M, Xue M, Zhang Y, Deng X, et al. Identification and Optimization of Contributing Factors for Precocious Puberty by Machine/Deep Learning Methods in Chinese Girls. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:892005. [PubMed ID: 35846287]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC9279618]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.892005.

-

7.

Yu T, Yu Y, Li X, Xue P, Yu X, Chen Y, et al. Effects of childhood obesity and related genetic factors on precocious puberty: protocol for a multi-center prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):310. [PubMed ID: 35624438]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC9135982]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03350-x.

-

8.

Fu D, Li T, Zhang Y, Wang H, Wu X, Chen Y, et al. Analysis of the Incidence and Risk Factors of Precocious Puberty in Girls during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Endocrinol. 2022;2022:9229153. [PubMed ID: 36213197]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC9534639]. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9229153.

-

9.

Lanari D, Mangiavacchi L, Pasqualini M. Adolescent sexual behaviour and academic performance of Italian students. Genus. 2020;76:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00093-4.

-

10.

Sunny BS, DeStavola B, Dube A, Price A, Kaonga AM, Kondowe S, et al. Lusting, learning and lasting in school: sexual debut, school performance and dropout among adolescents in primary schools in Karonga district, northern Malawi. J Biosoc Sci. 2019;51(5):720-36. [PubMed ID: 31030681]. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932019000051.

-

11.

Korbi A, Amina C, Korbi I, Amamou B, Ennaceur F, Hajji A, et al. Adolescents in Sexuality of Tunisian Teenagers. HIV AIDS Res J. 2018;1(2):1000107.

-

12.

Sales-Wuillemin E. [Survey methodology: From interview to questionnaire]. In: Bromberg M, Trognon A, editors. Course in Social Psychology 1. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 2006. p. 45-77. French.

-

13.

Courtois R. Conception et définition de la sexualité: les différentes approches [Conceptions and definitions of sexuality: the different approaches]. Ann Med Psychol. 1998;156(9):613-20. French.

-

14.

Potard C, Courtois R, Clarisse R, Le Floc'h N, Thomine M, Reveillere C. [Pubertal maturation, physical self-esteem and sexuality in a sample of French adolescents]. Encephale. 2016;42(2):138-43. French. [PubMed ID: 26806140]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2015.12.015.

-

15.

Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc. 1988;17(2):117-33. [PubMed ID: 24277579]. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537962.

-

16.

Clawson A, Strang JF, Wallace GL, Gomez-Lobo V, Jack A, Webb SJ, et al. Parent-Child Concordance on the Pubertal Development Scale in Typically Developing and Autistic Youth. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2020;77:101610. [PubMed ID: 32863862]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC7449027]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101610.

-

17.

Pompeia S, Zanini GAV, Freitas RS, Inacio LMC, Silva FCD, Souza GR, et al. Adapted version of the Pubertal Development Scale for use in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2019;53:56. [PubMed ID: 31432913]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC6703897]. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2019053000915.

-

18.

Koopman-Verhoeff ME, Gredvig-Ardito C, Barker DH, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Classifying Pubertal Development Using Child and Parent Report: Comparing the Pubertal Development Scales to Tanner Staging. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(5):597-602. [PubMed ID: 31974011]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.308.

-

19.

Thijssen S, Collins PF, Luciana M. Does pubertal stage mediate the association between family environment and structure and function of the amygdala-mPFC circuit? A replication study of the longitudinal ABCD cohort. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2022;56:101120. [PubMed ID: 35716638]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC9213703]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101120.

-

20.

Kuo JH, Ubeda Herrera JJ, Liu CY, Lee TH, Strong C, Lin CY, et al. Relationship Between Weight Status and Self-Image Mediated by Pubertal Timing and Athletic Competence: A Cohort Study With Taiwanese Adolescents. Front Public Health. 2022;10:890751. [PubMed ID: 35937217]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC9353071]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.890751.

-

21.

Javdani S, Sadeh N, White HI, Emerson E, Houck C, Brown LK, et al. Contextualizing pubertal development: The combination of sexual partners' age and girls' pubertal development confers risk for externalizing but not internalizing symptoms among girls in therapeutic day schools. J Adolesc. 2019;71:84-90. [PubMed ID: 30641301]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC6428577]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.01.001.

-

22.

Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: Developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Dev Rev. 2008;28(2):153-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.06.001.