Abstract

Context:

Divided attention is impaired in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The influence of divided attention on people with AD has been considered from different perspectives, such as motor ability, cortical responses, performance in divided attention evaluation tasks, and comparison of divided attention and directed and focused attention. The purpose of the current study was to investigate divided attention in AD patients from these different perspectives.Evidence Acquisition:

An electronic search was performed in January and February 2016 in PubMed, Science Direct, Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Ovid databases to obtain relevant articles published from 1980 to 2015. The keywords used included “Alzheimer’s disease”, “attention”, and “divided attention”. The articles obtained were studied using the following standard protocol for inclusion criteria written in the English language, the focus of studies was on divided attention in AD, and no other types of cognitive ability. From the 60 articles found, 10 articles that were adhered to the inclusion criteria were selected for consideration.Results:

The 10 studies reviewed considered divided attention in AD from different domains. These domains showed that AD patients had impaired performance in tasks that required divided attention and showed deficits in motor tasks stemming from the negative effects of impaired divided attention on motor ability. Different types of brain deficits have been observed in neuroimaging techniques in individuals with AD during divided attention tasks. Those with AD showed greater impairment for divided attention than for directed and focused attention.Conclusions:

Divided attention influences the lives of those with AD from several perspectives. These include the inability to focus on two or several relevant stimuli simultaneously that require divided attention rather than directed and focused attention and a deficit in the performance of motor tasks such as gait and other problems in daily life, such as falling. In addition, depression also had a negative effect on divided attention. Depressed AD patients had more difficulty in daily activities than AD patients without depression. The areas of the brain involved in divided attention in individuals with AD differ from those involved in unaffected people.Keywords

Alzheimer’s Disease Divided Attention Deficit Gait Disorder Assessment

1. Context

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease in older people. It is estimated that 5.5 million Americans will experience Alzheimer-type dementia (1). Alzheimer’s disease results in severe impairment of cognitive components such as memory, executive function, language, and attention (2).

All mental activities require attention (3). It has been stated that attention dysfunction is the cornerstone of decreased cognitive function in AD (4). Generally, attention is categorized as selective, sustained, and divided (3). Nevertheless, divided attention can be considered as only one part of selective attention (4). Divided attention is accompanied by concentration on more than one stimulus or task simultaneously (3-5). This type of attention is likely to be the earlier domain of attention control, which is influenced in AD (3, 4, 6-16).

The effects of divided attention on life are obvious as well as varied and a few studies have considered them separately thus far. Nestor et al. (17), used the duel task reaction time paradigm to investigate divided attention in mild to moderate AD and found that individuals with AD at all stages show impairment in this task. Some studies have demonstrated that divided attention is more affected than directed attention in AD. It has been understood that the primary deficit in the attention of individuals with AD is impairment in the distribution of attentional resources between multiple stimuli (12, 13, 15). The reason for this impairment is disengagement and shifting of attention between multiple stimuli (16, 18, 19). Divided attention affects functional mobility such as gait and postural stability. Thus, individuals with AD take shorter steps, have a lower gait rate, reduced step alternation, and inconsistency in gait when compared with the normal population (20-24).

The purpose of the current study is to investigate divided attention in individuals with AD from different domains.

The research questions that were addressed in this study are:

- In which brain regions does divide attention function in normal and AD brains?

- Is divided attention one of the most vulnerable types of attention in Alzheimer’s disease?

- What tests demonstrate divided attention deficits in AD?

- What is the importance of such tests in AD?

- What does the capacity-sharing theory say about divided attention performance for simultaneous cognitive and motor tasks?

- What are the differences between people suffering from AD with and without depression on divided attention tasks?

2. Evidence Acquisition

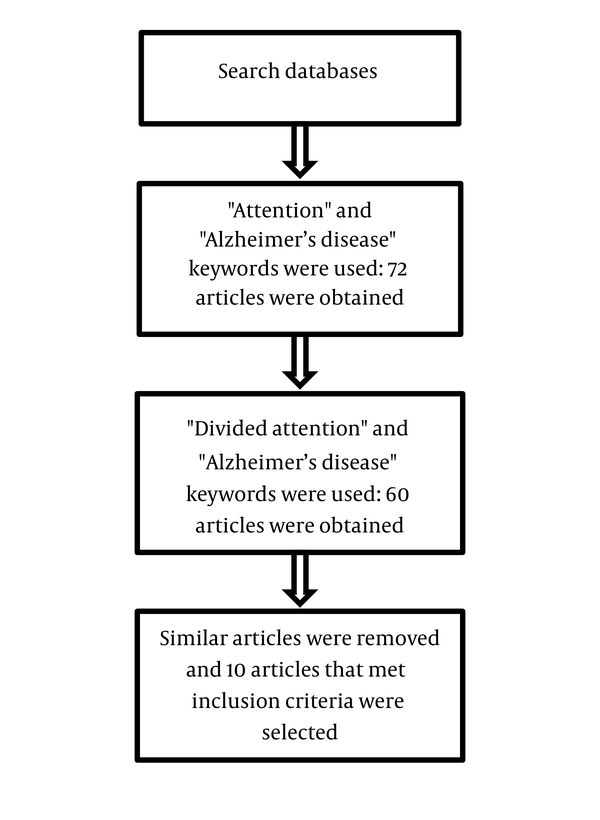

An electronic search was performed during January and February 2016 in PubMed, Science Direct, Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Ovid databases as well as related journals to obtain relevant articles published from 1980 to 2015. For this study, some inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered. The inclusion criteria were: written in the English language, availability of the full text of articles, type of articles were original as well as review articles and the focus of studies was on divided attention and AD, and all papers have been published between 1989-2015. The exclusion criteria were: studies that were published before 1980 and in a language other than English, studies regarding the AD and other cognitive abilities, such as working memory and executive function. In the first phase of the search, “attention” and “Alzheimer’s disease” keywords were used and 72 articles were obtained. In the second phase of the search, “divided attention” and “Alzheimer’s disease” keywords were used and 60 articles were obtained. Implementing the inclusion criteria resulted in 10 articles. A summary of the search and access to articles stages are shown in Figure 1.

Stages of search to obtain relevant articles.

3. Results

A total of 10 articles that were adhered to all exclusion and inclusion criteria were ultimately selected. These articles considered divided attention in individuals with AD during divided attention tasks, functional mobility in AD patients relevant to divided attention, comparison of divided attention and other kinds of attention, assessment of these kinds of attention, and the influence of depression on divided attention in individuals with AD. Table 1 indicates a summary of this review.

Review Studies

| Author | Aim of Study | Participants | Materials & Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Tests | Other Tests | |||

| Nestor et al. (1991) (17) | Considering the relevance between reaction time assessment probate single and duel tasks qualification and brain metabolism resting levels. | Mean age of ten patients was 66.4± 9.2 and mean education of them was 15.5 ± 3.0 years. Mean MMSE scores was 23 ± 2.9. Mean age of nine persons as control group was 66.5 ± 3.6 years and mean education of 16.4± 2.4 years (matched with the patient group). | 1. Auditory simple reaction time task, 2. Visual choice reaction time task, 3. Visual choice reaction time and Auditory simple reaction time tasks were presented simultaneously | 1. Wechsler adult intelligence scale, 2. Wechsler memory scale, 3. MMSE |

| Johannsen et al. (1999) (25) | Comparison patterns of cerebral activation during divided and sustained attention between Persons with AD and normal elderly population. | Sixteen right-handed persons with AD, without depression and vascular dementia with mild to moderate severity. | 1. Visual and vibrotactile stimulus in the format of attention task, 2. PET scan | 1. MMSE, 2. Mattis dementia, scale, 3. Hamilton’s depression scale, 4. Oldfield’s handedness scale |

| Nebes et al. (1989) (8) | Comparison between normal young and elderly individuals with persons with AD on focused and divided attention. | Eighteen patients with mean age 70.6. Eighteen older with mean age 70.4 and eighteen young normal persons with mean age 23.1 as a control group. The older control group was matched for age, sex and education and young group sex and education. | 1. Presenting letters in one-channel tachistoscope | 1. Dvorine Color, Vision test, 2. Boston naming test, 3. Abbreviated similarities subtest of the Wechsler adult intelligence scale. 4. Verbal fluency test, 5. Trail making test |

| Filoteo et al. (1992) (10) | Investigating performances between individuals with AD and normal group on divided and directed attention tasks of RT. | Fourteen AD patients and fifteen normal control that matched with patient group in terms of sex, age and education. | 1. Global-local stimuli | 1. Boston naming test, 2. Test of visuospatial abilities, 3. Block design subtest of the Wechsler adult intelligence scale |

| Grady et al. (1989) (7) | Considering the causes of inability in dichotic performance (inability in the divided attention or the inability to perceive degraded auditory stimuli | Thirty-two AD patients with mild to moderate severity and with the mean age of 63.6 ± 9.4. 33 healthy volunteers, age-matched to the patients, with the mean age 63.7 ± 7.0. All the participants had normal hearing sensitivity. With high-frequency cochlear hearing deficits, bilaterally. | 1. SSW which is a doctrinal test in which attention sharing between diverse words. These words are presented to each ear concurrently, 2. Degraded monotic speech material that presented monaurally is a test for assessing auditory processing | |

| Sheridan et al. (2003) (26) | To assess how cognitive function and divided attention affects gait in persons with AD. | Twenty-nine persons with AD without stroke, Parkinson disease and gait disorders followed by disease of primary motor areas. The patient must be able to walk without cooperation. | 1. Duel task (walking duration talking) | 1. Mini-mental state examination, 2. Clock drawing test, 3. Verbal fluency, 4. Digit span, 5. Clinical dementia rating scale |

| Pettersson et al. (2007) (27) | Considering the influence of cognition on motor performance using two simple tasks (walking and talking) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and a person with AD. | Six AD group, six mild cognitive impairment group, and twenty-five normal control group with 45 to 64 ages. | 1. Duel task test (talk while walking) | Another task: 2. MMSE. |

| De Melo-Borges et al. (2015) (28) | Considering whether functional mobility with or without divided attention would be a suitable test in distinguishing persons with mild cognitive impairment from healthy elderly participants from cognitive aspect and persons with mild AD. | 104 participants with 60 to 88 ages with different degree of cognitive impairment. Minimum years of education were four. Participants must be without orthopedic and neurological disorders. | 1. TUG | 1. MMSE, 2. Short, cognitive test, 3. Executive interview – exit 25, 4. Verbal fluency, animals category |

| Nakaaki et al. (2007) (29) | Emphasizing specific impairments of executive functions and attention, such as divided attention and cognitive flexibility in patients with depression. | Twenty persons with AD with depression and twenty one persons with AD without depression that matched with persons with AD with depression in sex, age, MMSE score, and education. Twenty one normal elderly control group. | 1. Duel task (pencil and paper measure) | 1. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised, 2. Wechsler memory scale-Revised, 3. Stroop test, 4. Letter fluency test, 5. Structured interview, guide for the Hamilton rating scale for depression, 6. Rey-osterrieth complex figure, 7. Trial making test, 8. Digit symbol test |

| Rodda et al. (2011) (14) | Investigating whether SCI (individuals with memory deficit, but with intact neurocognitive skills) would be related to changes of brain activation in the attentional processing. | Eleven individuals with SCI with mean age 64.6 and mean years in education 10.9 and ten control group with mean age 68 and mean years in education 10.1. | 1. The divided attention task included 10 alternating blocks of divided attention and control attention conditions | 1. Memory clinic assessment include psychiatric interview, mental state examination, 2. Neurocognitive measures include Cambridge cognitive examination, MMSE, 3. Logical memory test, 4. Wechsler memory scale III, 5. National adult reading test, 6. Trail making test, 7. letter fluency, 8. Naming and ideational fluency |

Several studies examined the brain activity and cortical responses in AD sufferers during divided attention tasks. Generally, Nestor et al. (17), found that there is a correlation between brain metabolism dysfunction (in the right frontal and parietal lobes) and response to divided attention tasks in Alzheimer patients. Johannsen et al. (25), stated that there were deficits in frontal performance during divided attention tasks in individuals with the AD. In addition, brain activity patterns become weaker in persons with the AD when faced with the complexity of divided attention tasks.

Other articles studied the performance of AD patients during divided attention tasks. Nebes et al. (8), showed a similarity of function of Alzheimer patients and the normal control group in visual search tasks for divided attention assessment. In the other words, performance in the divided attention tasks becomes weaker in Alzheimer patients with increasing array size of the stimulus (complexity). Filoteo et al. (10), stated that AD patients were impaired for inconsistent global-local stimuli (different forms at the global and local levels, such as a large “1” made from many small “2s”) rather than consistent global-local stimuli (same form at global and local levels, such as a large “1” made from many small “1s”). They found that impairment occurs during the shifting of attention from one level to another. Grady et al. (7), showed that Alzheimer patients showed greater impairment on a dichotic test than on a monotic test.

Sheridan et al. (26), examined the effects of divided attention on the motor abilities of individuals with AD. They found that patients with AD showed deficits in divided attention exhibited impairment in motor skills and step frequency, rate (time), and length of step as well as impairment in gait, which eventually leads to falls. Pettersson et al. (27), concluded that gait was influenced in a dual-task condition for individuals with AD compared with normal people. De Melo-Borges et al. (28), stated that in all phases of a TUG task (Table 1), participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) performed worse than the normal group and better than the AD group, especially on the divided attention task.

Nakaaki et al. (29), concluded that depressed individuals with AD performed worse on cognitive flexibility and divided attention tasks than individuals with AD without depression. In the last study, Rodda et al. (14), stated that Subjective Cognitive Impairment (SCI) and control groups did not differ on neurocognitive or socio-demographic measures, however, on the fMRI, the SCI group showed enhanced activation in the caudate bilateral thalamus, posterior cingulate, Hippocampus, and Para hippocampal gyrus during the divided attention task.

The only limitation of the current study was the lack of access to articles published before 1989, which could have had negative effects on the results.

4. Conclusions

This section addresses the questions posed in the Context section. The network hypothesis states that central processors are separate modules with specific anatomical regions that allocate different resources for various attention tasks and attention functions for selective, sustained, and divided attention (30). The frontal, parietal, basal ganglia, and thalamus have been found to be involved in divided attention (17, 31). The temporal, middle frontal, posterior cingulate, and subcortical areas are also affected by Alzheimer’s disease (7).

Cortical response to sustained and divided attention in AD was as follows; in both types of attention, the medial frontal area was activated and the frontal and posterior cingulate structures and subcortical sites were deactivated in AD. In contrast, in normal individuals, both divided and sustained attention excited activation of the inferior parietal lobule and the medial frontal gyrus in the right direction; however, only the anterior cingulate gyrus was activated in sustained attention (25). Therefore more cortical areas are activated during divided attention than sustained attention in AD patients rather than in the normal group (25). The cortical area involved in divided attention tasks can be used as a differentiation tool for a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals suffering from AD perform like normal people during the focused (8) and directed attention (10) tasks, therefore divided attention is more sensitive to brain damage than other tasks.

A number of dual or multiple tasks have been used in previous studies to assess divided attention. These tasks are listed below:

- Auditory-simple reaction time and visual choice reaction time tasks are presented concurrently (17).

- Visual and vibro-tactile stimuli are presented simultaneously (25).

- Global-local stimuli (in this task, the subjects must simultaneously attend to both global and local stimuli and report whether or not the global form of the number with numbers written by them is the same) (10).

- The staggered spondaic word test (attention should be shared between different words presented to each ear simultaneously) (17).

- Talk-while-walking (TWW) (26, 27)

- Timed-up-and-go (TUG) test in four experimental stages: (1) single TUG task, (2) TUG plus a cognitive task, (3) TUG plus a manual task, (4) TUG plus manual, and cognitive tasks. In the first phase, the single TUG task was implemented alone. In the second phase, the TUG test was incorporated with a verbal fluency task (animal category). In the third phase, the TUG test was performed while carrying a full glass of water. The fourth stage triple TUG test uses both manual and cognitive tasks (a verbal fluency test (animal category) while carrying a full glass of water). The results showed that TUG 2 and 4 were more impaired than TUG 1 and 3, which suggests that the cognitive tests interfere with functional mobility more than the motor tests. This finding underlines the impression of the task of cognition as the highest requesting factor in the divided attention task (28). These phases of the TUG test could be used to discriminate between MCI and AD groups, due to the fact that those suffering from AD require more time to complete this task.

It has been demonstrated that individuals with AD reveal impaired function on clinical tests (7, 10, 17, 27). Daily living activities are often multiple functions in which divided attention is required for implementation. Testing can accurately reflect divided attention deficits in AD and are useful for differential diagnosis of divided attention and other types of attention deficit. These tests help during assessment and treatment of different dimensions of divided attention dysfunction in people with AD. They can be used as rehabilitation intervention to improve the multiple functions that are required in daily living in people suffering from AD.

Gait requires more attention in parallel with attentional sources during aging. Capacity-sharing theory states that implementing a talking task while walking may cause a sluggish gait or lagged performance on the second task (talking, manual and/or cognitive task). This is especially true for the elderly (32). Several studies have shown that divided attention impairment causes gait deficits (33, 34). These results support the idea that over-learned motor skills such as gait require attentional control. Attentional capacity as a plexus function requires to intact perception. The absence of sensory integration of the posterior higher cortical area disturbs executive capacity (26). Jahanshahi et al. (35), concluded that gait, as a routine or previously learned action, does not require attentional control. Stern et al. (36) illustrated the importance of input and attention from the superior cortical motor centers to implement typical movements, similar to what is required for learning a recent motor task. These results protect the important effect of executive function and attention on gait variability in individuals with AD.

Nakaaki et al. (29), suggested that depression effects people with AD and can increase deficits in cognitive and divided attention skills. In AD, symptoms of depression are known to happen from the primary phase of the disease. It also affects divided attention and executive functions, leading to worsening of the symptoms in individuals with AD. Neuroimaging research has shown that dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex is a significant component of depression in patients with AD (37). Other researchers have demonstrated that individuals suffering from AD with depression showed hypo-metabolism in the frontal lobe comprising the left anterior cingulate and superior frontal cortices of both directions and the right anterior cingulate gyrus (37).

Research has demonstrated that either the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or the anterior cingulate gyrus play significant roles in the implementation of the dual tasks. These have shown significant impairment in depressed individuals with AD (37-40). These results support the idea that dual-task dysfunction is related to depression and divided attention in individuals with AD. Unlike divided attention, which is disturbed in depressed people with AD, there was no significant effect for other types of attention, such as sustained and selective attention. The necessity of investigating divided attention in depressive people with AD is evident.

References

-

1.

Alzheimer's Association. 2017 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(4):325-73.

-

2.

Wimo A, Winblad B, Aguero-Torres H, von Strauss E. The magnitude of dementia occurrence in the world. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17(2):63-7. [PubMed ID: 12794381].

-

3.

Baddeley AD, Baddeley HA, Bucks RS, Wilcock GK. Attentional control in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 8):1492-508. [PubMed ID: 11459742].

-

4.

Perry RJ, Hodges JR. Attention and executive deficits in Alzheimer's disease. A critical review. Brain. 1999;122 ( Pt 3):383-404. [PubMed ID: 10094249].

-

5.

Van Z, Zomeren AH, Brouwer WH. Clinical neuropsychology of attention. Oxford University Press, USA; 1994.

-

6.

Belleville S, Chertkow H, Gauthier S. Working memory and control of attention in persons with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2007;21(4):458-69. [PubMed ID: 17605579]. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.21.4.458.

-

7.

Grady CL, Grimes AM, Patronas N, Sunderland T, Foster NL, Rapoport SI. Divided attention, as measured by dichotic speech performance, in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(3):317-20. [PubMed ID: 2919988].

-

8.

Nebes RD, Brady CB. Focused and divided attention in Alzheimer's disease. Cortex. 1989;25(2):305-15. [PubMed ID: 2758855].

-

9.

Nestor PG, Parasuraman R, Haxby JV. Speed of information processing and attention in early Alzheimer's dementia. Dev Neuropsychol. 1991;7(2):243-56.

-

10.

Filoteo JV, Delis DC, Massman PJ, Demadura T, Butters N, Salmon DP. Directed and divided attention in Alzheimer's disease: impairment in shifting of attention to global and local stimuli. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1992;14(6):871-83. [PubMed ID: 1452635]. https://doi.org/10.1080/01688639208402541.

-

11.

Parasuraman R, Haxby JV. Attention and brain function in Alzheimer's disease: A review. Neuropsychology. 1993;7(3):242.

-

12.

Baddeley A, Logie R, Bressi S, Della Sala S, Spinnler H. Dementia and working memory. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1986;38(4):603-18. [PubMed ID: 3809575].

-

13.

Parasuraman R, Nestor PG. Energetics of attention and Alzheimer’s disease. Energetics and human information processing. Springer; 1986. p. 395-407.

-

14.

Rodda J, Dannhauser T, Cutinha DJ, Shergill SS, Walker Z. Subjective cognitive impairment: functional MRI during a divided attention task. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(7):457-62. [PubMed ID: 20932721]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.07.003.

-

15.

Grimes AM, Grady CL, Foster NL, Sunderland T, Patronas NJ. Central auditory function in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1985;35(3):352-8. [PubMed ID: 3871922].

-

16.

Posner MI, Inhoff AW, Friedrich FJ, Cohen A. Isolating attentional systems: A cognitive-anatomical analysis. Psychobiol. 1987;15(2):107-21.

-

17.

Nestor PG, Parasuraman R, Haxby JV, Grady CL. Divided attention and metabolic brain dysfunction in mild dementia of the Alzheimer's type. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29(5):379-87. [PubMed ID: 1886681].

-

18.

Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain. Office of Naval Research; 1989.

-

19.

Parasuraman R, Greenwood PM, Haxby JV, Grady CL. Visuospatial attention in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Brain. 1992;115 ( Pt 3):711-33. [PubMed ID: 1628198].

-

20.

Buchner DM, Larson EB. Falls and fractures in patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. JAMA. 1987;257(11):1492-5. [PubMed ID: 3820464].

-

21.

Visser H. Gait and balance in senile dementia of Alzheimer's type. Age Ageing. 1983;12(4):296-301. [PubMed ID: 6660138].

-

22.

Alexander NB, Mollo JM, Giordani B, Ashton-Miller JA, Schultz AB, Grunawalt JA, et al. Maintenance of balance, gait patterns, and obstacle clearance in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1995;45(5):908-14. [PubMed ID: 7746405].

-

23.

O'Keeffe ST, Kazeem H, Philpott RM, Playfer JR, Gosney M, Lye M. Gait disturbance in Alzheimer's disease: a clinical study. Age Ageing. 1996;25(4):313-6. [PubMed ID: 8831878].

-

24.

Montero-Odasso M, Bergman H, Phillips NA, Wong CH, Sourial N, Chertkow H. Dual-tasking and gait in people with mild cognitive impairment. The effect of working memory. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:41. [PubMed ID: 19723315]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC2748075]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-9-41.

-

25.

Johannsen P, Jakobsen J, Bruhn P, Gjedde A. Cortical responses to sustained and divided attention in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 1999;10(3 Pt 1):269-81. [PubMed ID: 10458942]. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.1999.0475.

-

26.

Sheridan PL, Solomont J, Kowall N, Hausdorff JM. Influence of executive function on locomotor function: divided attention increases gait variability in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1633-7. [PubMed ID: 14687395].

-

27.

Pettersson AF, Olsson E, Wahlund LO. Effect of divided attention on gait in subjects with and without cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20(1):58-62. [PubMed ID: 17341772]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988706293528.

-

28.

De Melo Borges S, Radanovic M, Forlenza OV. Functional mobility in a divided attention task in older adults with cognitive impairment. J Mot Behav. 2015;47(5):378-85. [PubMed ID: 25610990]. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222895.2014.998331.

-

29.

Nakaaki S, Murata Y, Sato J, Shinagawa Y, Tatsumi H, Hirono N, et al. Greater impairment of ability in the divided attention task is seen in Alzheimer's disease patients with depression than in those without depression. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(4):231-40. [PubMed ID: 17308387]. https://doi.org/10.1159/000099633.

-

30.

Corbetta M, Miezin FM, Dobmeyer S, Shulman GL, Petersen SE. Selective and divided attention during visual discriminations of shape, color, and speed: functional anatomy by positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 1991;11(8):2383-402. [PubMed ID: 1869921].

-

31.

Vohn R, Fimm B, Weber J, Schnitker R, Thron A, Spijkers W, et al. Management of attentional resources in within-modal and cross-modal divided attention tasks: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(12):1267-75. [PubMed ID: 17315224]. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20350.

-

32.

Yogev-Seligmann G, Hausdorff JM, Giladi N. The role of executive function and attention in gait. Mov Disord. 2008;23(3):329-42. quiz 472. [PubMed ID: 18058946]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC2535903]. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21720.

-

33.

Muir SW, Speechley M, Wells J, Borrie M, Gopaul K, Montero-Odasso M. Gait assessment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: the effect of dual-task challenges across the cognitive spectrum. Gait Posture. 2012;35(1):96-100. [PubMed ID: 21940172]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.08.014.

-

34.

Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, Logiudice D, Lautenschlager NT, Dodd KJ. Balance and mobility dysfunction and falls risk in older people with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(1):12-23. [PubMed ID: 22157433]. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31823caeea.

-

35.

Jahanshahi M. Willed action and its impairments. Cogn Neuropsychol. 1998;15(6-8):483-533. [PubMed ID: 22448836]. https://doi.org/10.1080/026432998381005.

-

36.

Stern Y, Moeller JR, Anderson KE, Luber B, Zubin NR, DiMauro AA, et al. Different brain networks mediate task performance in normal aging and AD: defining compensation. Neurology. 2000;55(9):1291-7. [PubMed ID: 11087770].

-

37.

Liao YC, Liu RS, Lee YC, Sun CM, Liu CY, Wang PS, et al. Selective hypoperfusion of anterior cingulate gyrus in depressed AD patients: a brain SPECT finding by statistical parametric mapping. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16(4):238-44. [PubMed ID: 14512719]. https://doi.org/10.1159/000072808.

-

38.

Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, Ikejiri Y, Imamura T, Shimomura T, et al. Frontal lobe hypometabolism and depression in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998;50(2):380-3. [PubMed ID: 9484357].

-

39.

Drevets WC. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11(2):240-9.

-

40.

Jiang Y. Resolving dual-task interference: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2004;22(2):748-54. [PubMed ID: 15193603]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.043.