Abstract

Background:

The relationship between bipolar disorder (BD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is investigated in several studies. According to the reports, the comorbidity of these two-disorders is more than the general population.Objectives:

The current study aimed to compare the severity of OCD in different episodes of BD.Methods:

This cross-sectional (descriptive-analytic) study included 90 patients referred to Baharan Psychiatric Center affiliated to the Zahedan University of Medical Science in 2019 with a primary diagnosis of BD according to Semi-structured interview (SCID). The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive scale was used to measure the severity of OCD symptoms in different episodes of BD.Results:

The severity of OCD symptoms in the depression group was significantly higher than the manic (P < 0.01) and remission groups (P < 0.01).Conclusions:

Mood state influences the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Since the course of disorder in the comorbidity of these two disorders become chronic and diagnosis, and the OCD is difficult in the manic episode; it is necessary to be aware when diagnosing BD or OCD.Keywords

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Bipolar Disorder Mood Disorders

1. Background

The key feature of bipolar disorder (BD) is the tendency of manic episodes that can be alternate with depressive episodes. The two major categories of BD are bipolar I disorder, which includes at least one manic episode that can be alternated with depressive episodes, and Bipolar II Disorder, which includes at least one episode of hypomania that is influenced by one or more than one episode of depression. The obsession-compulsive disorder (OCD) is identifying by the presence of the obsessions that are recurrent and persistent intrusive thoughts, urges or images, and/or the compulsions that are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that feel driven to act in response to the obsession or as rules that must be applied rigidly (1).

The association between OCD and mood disorders has been reported in different studies (2-4). Depression is one of the most common comorbid disorders with OCD, although BD comorbid with 10% to 20% of patients with primary OCD diagnosis and the rate of comorbidity of OCD with primarily BD diagnosis is reported to be 9% to 35%, which is higher than the general population (2, 4-8). In some studies, OCD is reported to be rare in Manic episodes (9). Moreover, some studies have shown that the OCD relapses after the manic episode or at the onset of depressive episodes (10, 11).

It seems that OCD symptoms decline in manic and hypomanic episodes but increases in depressive episodes. Several studies have shown that comorbidity of OCD with major depressive disorder results in increased severity of OCD symptoms, while comorbidity of BD with OCD is the cause of recurrent OCD symptoms (12, 13). The results of recent studies regarding the association of these two disorders indicate that the onset age of BD in BD-OCD comorbidity is lower than BD without OCD. BD may have not any effect on the phenomenology of OCD, but features like the periodicity of the OCD symptoms, seasonality, rapid cycling, earlier onset of BD, and impulsivity in the BD-OCD may describe a different form of BD (14).

The findings on the treatment of BD-OCD comorbidities indicate that Antidepressants can be a trigger to relapse manic episodes, and Benzodiazepines can cause addiction problems, so Cognitive-behavioral therapy can be an alternative therapy.

A study indicated that since the combination of aripiprazole and clozapine can reduce OCD symptoms without destabilizing the patient’s mood, it can be an appropriate medication (15), but other research suggested that mood stabilizers should be the primary goal in treating BD-OCD comorbidities (16). On the other hand, BD-OCD patients may respond to the appropriate dosage of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics for symptoms of both disorders (17).

Many studies have investigated the BD symptoms in OCD patients, but few of their participants were patients with primary BD diagnosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that the severity of OCD symptoms should be rare or lower in manic episodes compared to the depressive episode.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to compare the severity of OCD symptoms in different episodes of BD.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

The current cross-sectional (descriptive-analytic) study is conducted in 2019 on 90 patients who were referred to the psychiatric hospital of Baharan affiliated to the Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (Iran) with a primary diagnosis of BD according to the semi-structural clinical interview.

The inclusion criteria included having a primary diagnosis of a bipolar mood disorder, being aged > 18, and the ability to answer the questions. Exclusion criteria were having any psychiatric disorders other than OCD or BD, having neurological and organically problems, a history of substance abuse, and being in a mixed episode of BD.

A psychiatrist diagnosed the patient by clinical interview; then, a clinical psychologist performed a diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder independently with a semi-structural interview (SCID-I). Then, patients were divided into three groups according to their current episode (30 patients in the Manic group, 30 patients in the depressive group, and 30 patients in remission). By using the obsessive-compulsive scale of Yale-Brown the severity of OCD symptoms was measured and compared among different groups.

3.2. Measurements

The Y-BOCS (Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive scale): This questionnaire is designed as a semi-structured interview to assess the severity of obsession and compulsion symptoms. It consists of 10 questions, which are scored by a four-point Likert scale, and its cut point for significant symptoms is 14 (18). The validity and reliability of the Persian version are 0.64 and 0.84, respectively (19).

3.2.1. Semi-Structured Interview

Semi-structured interview (SCID-I) is a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of an axis I disorder of DSM-IV. It should be conducted by a mental health staff who is familiar with the DSM (20). The validity and reliability of the Persian version are 0.85 and 0.55, respectively (21, 22).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 24. Descriptive statistics indexes such as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentile were employed. The independent t-test was used for comparing the severity of OCD symptoms between men and women, and the one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test was used to examine the severity of OCD symptoms in three groups.

4. Results

Of 90 patients, 67(74.4%) were male. The mean age of the patients was 35.08 ± 11.47. There was no significant correlation between age and OCD score. Socio-demographic details and the severity of OCD symptoms are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | Values | Mean Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | -3.14c | |

| Male | 67 (74.4) | |

| Female | 23 (25.6) | |

| Marital status | 2.45 | |

| Single | 31 (34.4) | |

| Married | 39 (43.3) | |

| Divorced | 20 (22.2) | |

| OCD symptoms severity | ||

| Manic episode | 2.53 ± 4.73 | |

| Depressive episode | 11.76 ± 12.73 | |

| Remission | 2.37 ± 4.57 |

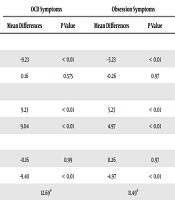

ANOVA analyses showed a significant difference between three groups concerning the total score (P value < 0.01, F = 12.69), obsession score (P value < 0.01, F = 11.49), and compulsion score (P value < 0.01, F = 10.61). One-Way ANOVA results are summarized in Table 2.

One-Way ANOVA Results of OCD Symptoms Score Different Between Bipolar Groups (N = 90)

| BD Episodes | OCD Symptoms | Obsession Symptoms | Compulsion Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Differences | P Value | Mean Differences | P Value | Mean Differences | P Value | |

| Manic | ||||||

| Depressive | -9.23 | < 0.01 | -5.23 | < 0.01 | -4.00 | < 0.01 |

| Remission | 0.16 | 0.575 | -0.26 | 0.97 | 0.43 | 0.91 |

| Depressive | ||||||

| Manic | 9.23 | < 0.01 | 5.23 | < 0.01 | 4.00 | < 0.01 |

| Remission | 9.04 | < 0.01 | 4.97 | < 0.01 | 4.43 | < 0.01 |

| Remission | ||||||

| Manic | -0.16 | 0.99 | 0.26 | 0.97 | -0.43 | 0.91 |

| Depressive | -9.40 | < 0.01 | -4.97 | < 0.01 | -4.43 | < 0.01 |

| F | 12.69a | 11.49a | 10.61a | |||

Tukey’s post hoc test was used to track the differences between the three groups. The results showed that the mean difference in the total score of OCD symptoms in the manic group (2.53 ± 4.73) was significantly lower than the depressive group (11.76 ± 12.73) (P value < 0.001). Also, the mean difference of the Remission group (2.37 ± 4.57) was significantly lower than the depressive group (P value < 0.001), there was no significant difference between the manic and remission groups. The separate scores of obsession and compulsion showed the same results as the total score.

5. Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the severity of OCD symptoms in different episodes of BD. Ninety patients with a primary diagnosis of BD were divided into three groups (i.e., manic, depressive, and remission). Then the severity of OCD symptoms was assessed and compared. As our hypothesis, patients in the depressive group had higher OC symptoms scores, compared to the manic and remission groups. The findings of this study indicated that the mood state affects the severity of OC symptoms. Also, BD patients on remission had the lowest severity of OC symptoms compared to the manic and depressive groups.

Although the comorbidity rate of OCD and BD disorders is significant concerning the epidemiology and clinical contexts (23, 24), some studies reported that in a manic episode, the appearance of OCD symptoms is very rare, but that relapse after remission of manic episode or at the onset of a depression episode (9, 10). The results of this study are similar to the findings of Jeon et al., which showed that in two-thirds of 314 patients with the OCD-BD diagnose, OCD symptoms had the most severity in the depressive episode; Besides, they showed that in BD-OCD, BD was associated with earlier onset (25). Karno et al. (9) showed that in the manic episode, the severity of the OCD was lower. Takasu et al. (26) also mentioned that the symptoms of patients with a primary diagnosis of OCD were improved during a manic episode and remission, but the severity of OCD symptoms was increased during the depression episode. In line with the findings of the current study, Ozdemiroglu et al. (14) also found the depression was correlated with active OC symptoms in BD patients. Furthermore, the majority of BD-OCD patients stated that their previous OC symptoms appeared predominantly during the depressive episodes. Mahasuar et al. (27) also showed worsening of OCD in depression episodes and improvement in the manic episode, which is similar to our findings and observations made previously. Besides, it supports the argument that comorbid BD affects the course of OCD in a distinct manner.

Previous studies on the comorbidity of these two disorders have shown that these patients have a higher chance of developing other disorders, including anxiety and substance abuse disorders (4, 28, 29). According to the findings on the comorbidity of these two disorders, it leads BD to a chronic course, but BD affects the OCD in a distinct way, which causes a seasonality course of OCD. It is likely that both disorders may have common pathophysiology, or emotion dysregulation may be the common etiology of these two disorders (30).

Regardless of the epidemiological associations, the comorbidity of these two disorders can be a dilemma, because serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that are commonly used to treat OCD increases the risk of manic episodes (31-33). A study on untreated BD patients using a PET scan showed that the neurotransmitter-serotonin binding potential in the insula and Dorso Cingular Cortex in BD-OCD patients is higher than those BD patients without OCD (34). Another study has shown that patients with both BD and OCD are more likely to have a family history of mood disorders and a lower probability of having a family history of OCD (35).

The manic episode might have contributed to the under-reporting of distressful OC symptoms, appearing in a lower comorbidity rate. In contrast, possible over-reporting of OC symptoms in patients with depression may have caused a mislabeling of ruminations as obsessions (24). It seems that BD has a patio plastic modulating effect on the course of OCD. Higher severity of OCD in depression episodes and improvement in the manic episode also is consistent with the changes in the expression of OCD due to BD (16, 36). Furthermore, some case reports described the onset of mania in response to treatment with SSRI in OCD patients, despite some of them had no history of BD (37).

5.1. Limitations

The findings of this study showed the severity of the OCD is significantly higher in women, therefore, it is suggested to further investigate the possible reasons for this difference. Also, because of the limited number of bipolar patients with mixed features or in the hypomanic episode, they were excluded from the study, so we suggest to investigate these patients in future studies. Additionally, it is better to adjust the psychotic features of patients in future studies, it is also recommended to compare the severity of the OCD symptoms in depression episodes of bipolar patients and unipolar depressive disorder. In the current study, the number of episodes of patients was not considered despite the possible effect on OCD severity.

5.2. Conclusions

The current study showed that OCD symptoms are rare in manic episodes and become more severe in the depressive episode. Based on the aforementioned studies, BD-OCD patients have higher rates of comorbidity with other disorders (like anxiety and substance abuse) and the suicide, and since this comorbidity makes the course of BD chronic and our study showed that OCD symptoms are less severe in a manic episode, health care providers should be aware of OCD symptoms when diagnosing BD.

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. 9. USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2019.

-

2.

Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, Hantouche E, Goodwin R, Ajdacic V, et al. Obsessive-compulsive syndromes and disorders: significance of comorbidity with bipolar and anxiety syndromes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(1):65-71. [PubMed ID: 15711895]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0576-8.

-

3.

Chen Y, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity for obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiat Res. 1995;59(1-2):57-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(95)02752-1.

-

4.

Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Pfanner C, Presta S, Gemignani A, Milanfranchi A, et al. The clinical impact of bipolar and unipolar affective comorbidity on obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Affect Disorders. 1997;46(1):15-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00075-x.

-

5.

Lensi P, Cassano GB, Correddu G, Ravagli S, Kunovac JL, Akiskal HS. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Familial-developmental history, symptomatology, comorbidity and course with special reference to gender-related differences. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(1):101-7. [PubMed ID: 8818377]. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.169.1.101.

-

6.

Masi G, Perugi G, Toni C, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, et al. Obsessive-compulsive bipolar comorbidity: focus on children and adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(3):175-83. [PubMed ID: 15013241]. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00107-1.

-

7.

Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2222-9. [PubMed ID: 15569893]. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222.

-

8.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock's Pocket Handbook of Clinical Psychiatry, 5th Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010.

-

9.

Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1094-9. [PubMed ID: 3264144]. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360042006.

-

10.

Raja M, Azzoni A. Clinical management of obsessive-compulsive-bipolar comorbidity: a case series. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(3):264-70. [PubMed ID: 15117406]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00109.x.

-

11.

Keck PE, Lipinski JF, White K. An Inverse Relationship Between Mania and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6(2):123???124. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004714-198604000-00022.

-

12.

Tukel R, Meteris H, Koyuncu A, Tecer A, Yazici O. The clinical impact of mood disorder comorbidity on obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(4):240-5. [PubMed ID: 16683062]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-006-0632-z.

-

13.

Tukel R, Oflaz SB, Ozyildirim I, Aslantas B, Ertekin E, Sozen A, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics in episodic and chronic obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(4):251-5. [PubMed ID: 17006935]. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20234.

-

14.

Ozdemiroglu F, Sevincok L, Sen G, Mersin S, Kocabas O, Karakus K, et al. Comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder with bipolar disorder: A distinct form? Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(3):800-5. [PubMed ID: 26561371]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.11.002.

-

15.

Ouali U, Zgueb Y, Ouertani A, Nacef F. Successful treatment of OCD-bipolar co-morbidity with clozapine – aripiprazole combination. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;41(S1):S757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1417.

-

16.

Amerio A, Odone A, Marchesi C, Ghaemi SN. Treatment of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2014;166:258-63. [PubMed ID: 25012439]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.026.

-

17.

Amerio A, Tonna M, Odone A, Stubbs B, Ghaemi SN. Course of illness in comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;20:12-4. [PubMed ID: 27025465]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2016.01.009.

-

18.

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1012-6. [PubMed ID: 2510699]. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008.

-

19.

Esfahani S, Motaghipour Y, Kamkari K, Zahiredin A, Janbozorgi M. Reliability and Validity of the Persian Version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). Iran J Psychiatry Clinl Psychol. 2012;17(4).

-

20.

Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(1):75-9. [PubMed ID: 20309842]. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.693.

-

21.

Sharifi V, Asadi SM, Mohammadi M, Amini H, Kaviani H, Semnani Y, et al. Reliability and feasibility of the Persian version of the structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Adv Cogn Sci. 2004;6(1):10-22.

-

22.

Amini H, Sharifi V, Asadi SM, Mohammadi MR, Kaviani H, Semnani Y, et al. [Validity of the Iranian version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) in the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders]. Payesh. 2008;7(1):49-57. Persian.

-

23.

Strakowski SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Goodwin DC. Comorbidity in mania at first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):554-6. [PubMed ID: 1348163]. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.149.4.554.

-

24.

Krüger S, Cooke RG, Hasey GM, Jorna T, Persad E. Comorbidity of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Bipolar Disorder. J Affect Disord. 1995;34(2):117-20. [PubMed ID: 7665803]. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(95)00008-b.

-

25.

Jeon S, Baek JH, Yang SY, Choi Y, Ahn SW, Ha K, et al. Exploration of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with bipolar disorder: The clinic-based prevalence rate, symptoms nature and clinical correlates. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:227-33. [PubMed ID: 28841485]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.012.

-

26.

Takasu Y, Kitamura H, Someya T. Significant interaction of manic episodes with the clinical course of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(4):443-4. [PubMed ID: 20653913]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02112.x.

-

27.

Mahasuar R, Janardhan Reddy YC, Math SB. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(5):423-33. [PubMed ID: 21851451]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02247.x.

-

28.

Joshi G, Wozniak J, Petty C, Vivas F, Yorks D, Biederman J, et al. Clinical characteristics of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(2):185-95. [PubMed ID: 20402711]. [PubMed Central ID: PMC2864069]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00795.x.

-

29.

Magalhaes PV, Kapczinski NS, Kapczinski F. Correlates and impact of obsessive-compulsive comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):353-6. [PubMed ID: 20579506]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.11.001.

-

30.

Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 2002;68(1):1-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8.

-

31.

Schruers K, Koning K, Luermans J, Haack MJ, Griez E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: a critical review of therapeutic perspectives. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111(4):261-71. [PubMed ID: 15740462]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00502.x.

-

32.

Fineberg NA, Reghunandanan S, Brown A, Pampaloni I. Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence-based treatment and beyond. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(2):121-41. [PubMed ID: 23125399]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412461958.

-

33.

Vieta E, Bernardo M. Antidepressant-induced mania in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(9):1282-3. [PubMed ID: 1503154]. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.149.9.aj14991282.

-

34.

Cannon DM, Ichise M, Fromm SJ, Nugent AC, Rollis D, Gandhi SK, et al. Serotonin transporter binding in bipolar disorder assessed using [11C]DASB and positron emission tomography. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(3):207-17. [PubMed ID: 16875929]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.005.

-

35.

Zutshi A, Kamath P, Reddy YC. Bipolar and nonbipolar obsessive-compulsive disorder: a clinical exploration. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(3):245-51. [PubMed ID: 17445518]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.12.005.

-

36.

Amerio A, Odone A, Liapis CC, Ghaemi SN. Diagnostic validity of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(5):343-58. [PubMed ID: 24506190]. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12250.

-

37.

Steiner W. Fluoxetine-induced mania in a patient with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(10):1403-4. [PubMed ID: 1897626]. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.10.1403b.