1. Introduction

The world health organization (WHO) has estimated that each year nearly one million people die from suicide. Moreover, up to twenty million people carry out suicide attempts annually. The WHO also reported that all through the world and within the last 45 years, suicide rates have increased by 60%, mostly among young people (1).

When we are dealing with a rising phenomenon like suicide, which is a very complicated act and can emerge in different ways and types, it is important to apply a characterization and categorization system. Scientists from diverse backgrounds including sociology, epidemiology, psychology, biology etc. have not only increased our knowledge about suicide (2) but also tried to categorize it based on different systems.

However, evidence suggests that the existing classification systems have their own limitations and there are overlaps between different categories. The aim of the present article was to introduce an algorithm characterization system for different types of suicide, which at the very least, might apply as an educational resource.

To fulfill this aim we will first consider the existing classification systems and discuss their limitations. Then we move on to discuss the fundamentals of any new categorization systems. Finally we will introduce a new characterization system that helps to better classify this complex phenomenon.

2. Existing Classification Systems and Their Limitations

One of the first scientists, who tried to classify suicide, was Durkheim. He showed how suicide is explicable with reference to social structure, and categorized it to the four following groups: Egoistic suicide, which results from ‘lack of integration of individual into the society’. Altruistic suicide in which the ‘individual is highly integrated into the society’. Anomic suicide, which results from ‘lack of regulation of the individual by the society’ and finally, Fatalistic Suicide, in which ‘an individual’s attitudes and values are highly regulated by the society’ (3).

Durkheim’s theory was based on a careful geographical observation of suicide rates over a long time period (4) and is used to predict associations between suicide rates and social indicators (5). However, it did not embrace all the recognized types of suicide such as murder suicide, etc. It also did not have the ability to encompass the new types of suicide as they have emerged. As a result, the ‘risk theory’ became the dominant approach to suicide (6). The fundamental of this theory is that suicide behavior is attributable to many causes, which have been divided to medical, psychological, biological, social, cultural and economic (7).

However, even this categorization has its own limitations. For example, there are overlaps across categories e.g. mental disorder might cause economic hardship (7). Additionally, some of the risk factors such as marital problems, which have previously been classified as psychosocial factors, could also attribute to biological factors (7, 8).

As a result, some scientists believe that the ‘risk theory’ offers little insight into suicide (6). Another categorization is active vs. passive suicide. Active suicide is an operative deliberate termination of life. Whereas passive suicide indicates placing oneself in a potentially lethal situation, such as not following treatment of a disease, or not leaving dangerous situations and not avoiding the conditions that may lead to death. Many factors such as cultural, moral, religious and psychological, as well as denial, evasiveness, guardedness and other issues are involved in suicidal ideations either actively or passively; egoistic, altruistic, anomic or fatalistic (9).

3. The Fundamentals of any New Categorization Systems

Any new classification system, which might be introduced, should be able to embrace all different types of suicide behavior. It should also have the ability to encompass any new types of suicide as they emerge.

Such new categorization system would eventually help researchers to better classify the diverse risk factors that trigger this mysterious human phenomenon. The proper classification of suicide cases would ultimately allow public health specialists and clinicians to provide more focused preventive services with a view to the changing society.

4. Proposing a New Categorization System

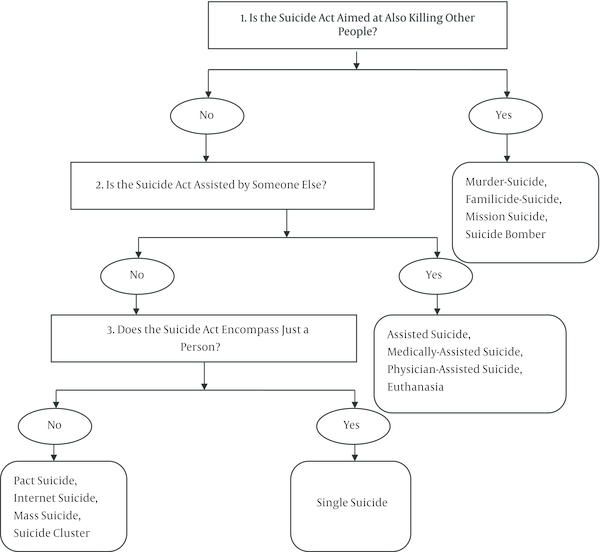

For our algorithm characterization, we should first ask the following three questions:

1- Is the suicide act also aimed at killing other people?

2- Does someone else assist the suicide act?

3- Does the suicide act encompass just a person?

Based on the responses to these questions we are able to categorize suicide as depicted in Figure 1.

Categorizing Different Types of Suicide by Asking Three Informative Questions

4.1. Is the Suicide Act Aimed at Also Killing Other People?

In case the response to this question is positive, then we encounter an unusual type of suicide usually called “murder-suicide”. In this type of suicide, a suicidal person wants to deliberately kill other people including family members or partners due to a number of reasons e.g. clinical depression and/or presence of divorce or separation, etc. (10, 11). In the case the suicidal person kills at the very least his spouse and one or more of his children before killing himself the case is referred to as “familicide-suicide” (12, 13).

In some other occasions a suicidal person wants to deliberately kill other people, who are considered to be her/his enemies. This type of suicide is generally called “suicide mission” and traditionally happens in armies, who protect their societies during wars and armed conflicts. Japanese Kamikaze is the most well known form of this type of suicide (14).

However, recently, a notable phenomenon, called “suicide bomber” occurs especially in the developing world. A person who might be a civilian, and not necessarily a soldier, carries out the suicide act by blowing himself/herself using explosive materials, and tries to kill as much as the armies or even the ordinary people from the opposite side as possible. Wars, armed conflicts, occupation, injustice, poverty in its wider concept etc. are the root causes of such suicidal acts (15-17).

It is important to realize that in these types of suicide the act of killing oneself after murdering others might occur to escape punishment or as a form of self-punishment or even to facilitate murdering. Therefore, these types of suicide should be clearly distinguished from suicides in which one only wants to kill him/herself (Please see below).

4.2. Is the Suicide Act Assisted by Someone Else?

In case the response to this question is positive, then we encounter another unusual type of suicide, usually called “assisted suicide”. The most common type of “assisted suicide” is “medically-assisted suicide” or “physician-assisted suicide” or “euthanasia” in which a terminally ill person might ask a doctor or a nurse or even a partner to help them to end their life using drugs or other methods.

This is one of the most controversial types of suicide all around the world (18-23) and it should be noted that “dignity” and “stigmatizing life with a disability” is the state which supporters and challengers apply to articulate their positions, respectively (24).

4.3. Does the Suicide Act Encompass Only One Person?

If the suicide act encompasses only one person, as found in a majority of suicides, then we encounter the most usual and most prominent form of suicide. This consists of almost all suicide acts in every society. A person decides to kill herself/himself based on complex interactions of diverse risk factors. Preventing such a single suicide is one of the most important but rather difficult tasks for mental health authorities in different societies (25, 26).

However, it is possible, in rare circumstances, for the suicide act to encompass more than one person. If it involves two or three people, then we encounter a phenomenon called “suicide pact” in which usually two people decide to kill themselves for personal reasons, either in a certain place and time or in different places (27-31). Sometimes, this kind of act might encounter more than two people but usually not more than three or four.

It would also possible for the Internet to work as a medium to spread the decision to carry out a suicide act, usually between two people in different geographical areas. There are also occasions where media, such as the Internet, may act as a catalyst for single or group suicide among people in different geographical areas. This type of suicide is named “Internet suicide” and evidence suggests that this type of suicide is growing rapidly in societies that have easy access to the Internet (32-34).

In other rare occasions it would also be possible for suicide acts to encompass more than a handful of people, which is called “mass suicide”. This kind of suicide usually occurs due to political, religious or economical reasons (35-39). For instance, evidence suggests that a number of Indian farmers carried out a suicide act due to the hardship of their economical situations (40, 41).

There is another term related to the situation in which a number of people may carry out a suicide act. This term is called “suicide cluster” and usually applies when the suicide thoughts, usually by the means of media (i.e. mass media, internet, etc.), are passed from a suicidal person to other people at risk of suicide. Suicide cluster might happen either in small societies or at national level and needs to be dealt with properly and appropriately (42-53).

5. Concluding Remarks

Algorithm characterization of suicide by asking three questions is a new method of characterization of this complex human behavior. This method not only adds new insight to the existing literature (54-58) yet embraces all diverse existing types of suicide. Furthermore, it allows classification of new emerging types of suicide by asking more questions and gathering more information.

The most prominent use of this characterization is to apply it as an educational epidemiological resource to teach about different types of suicide. This characterization would also eventually help researchers to better classify the diverse risk factors that trigger this mysterious human phenomenon. It might ultimately allow public health specialists and clinicians to provide more focused preventive services with a view to changing the society.

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

World Health Organization: Suicide Prevention. WHO; 2005, [cited 2013]. Available from: www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/.

-

2.

Gunnell DJ. The epidemiology of suicide. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2009;12(1):21-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260074076.

-

3.

Durkheim E. Suicide: a study in sociology. London: Routledge; 1952.

-

4.

Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4.

-

5.

Lester D. A regional analysis of suicide and homicide rates in the USA: search for broad cultural patterns. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1988;23(3):202-5. [PubMed ID: 3140396].

-

6.

Hood-Williams J. Studying suicide. Health Place. 1996;2(3):167-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/1353-8292(96)00010-x.

-

7.

Marusic A, Farmer A. Toward a new classification of risk factors for suicide behavior. Crisis. 2001;22(2):43-6. [PubMed ID: 11727890]. https://doi.org/10.1027//0227-5910.22.2.43.

-

8.

Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. A longitudinal twin study of 1-year prevalence of major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(11):843-52. [PubMed ID: 8215810].

-

9.

Simon RI. Passive suicidal ideation: Still a high-risk clinical scenario thorough risk assessment may reveal active suicide ideation. Curr Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):13-5.

-

10.

Eliason S. Murder-suicide: a review of the recent literature. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(3):371-6. [PubMed ID: 19767502].

-

11.

Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Hirsch CS. The epidemiology of murder-suicide. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3179-83. [PubMed ID: 1593740].

-

12.

Sisask M, Mark L, Varnik A. Internet comments elicited by media portrayal of a familicide-suicide case. Crisis. 2012;33(4):222-9. [PubMed ID: 22450037]. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000134.

-

13.

Scheinin L, Rogers CB, Sathyavagiswaran L. Familicide-suicide: a cluster of 3 cases in Los Angeles County. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2011;32(4):327-30. [PubMed ID: 21512375]. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e31821a555a.

-

14.

Gambetta D. Making Sense of Suicide Missions. USA: Oxford University Press; 2005.

-

15.

Lester D. Female suicide bombers and burdensomeness. Psychol Rep. 2010;106(1):160-2. [PubMed ID: 20402439]. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.106.1.160-162.

-

16.

Aggarwal N. Rethinking suicide bombing. Crisis. 2009;30(2):94-7. [PubMed ID: 19525169]. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.30.2.94.

-

17.

Kazim SF, Aly Z, Bangash HK, Harchandani BP, Irfan AB, Javed SM, et al. Attitudes toward suicide bombing in Pakistan. Crisis. 2008;29(2):81-5. [PubMed ID: 18664233]. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.29.2.81.

-

18.

McCormack R, Clifford M, Conroy M. Attitudes of UK doctors towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2012;26(1):23-33. [PubMed ID: 22190615]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311397688.

-

19.

Sjostrand M, Helgesson G, Eriksson S, Juth N. Autonomy-based arguments against physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia: a critique. Med Health Care Philos. 2013;16(2):225-30. [PubMed ID: 22161026]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-011-9365-5.

-

20.

Nitschke P, Stewart F. 'What's it got to do with you?' Challenging the medical profession's future in the assisted suicide debate. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(12):1017-9. [PubMed ID: 22122294]. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.623661.

-

21.

Riddell S. "If assisted suicide is legalised, are nurses best placed to do it?". Nurs Times. 2011;107(40):11. [PubMed ID: 22132485].

-

22.

Dyer C. Panel recommends that assisted suicide be legalised in Canada. BMJ. 2011;343(181):7496. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d7496.

-

23.

Paterson I, Forbes S. Should assisted suicide be legalised? Nurs Times. 2003;99(9):18-9. [PubMed ID: 12673980].

-

24.

Behuniak SM. Death with "dignity": the wedge that divides the disability rights movement from the right to die movement. Politics Life Sci. 2011;30(1):17-32. [PubMed ID: 22204677]. https://doi.org/10.2990/30_1_17.

-

25.

Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1372-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60372-x.

-

26.

Rezaeian M. Suicide among young Middle Eastern Muslim females. Crisis. 2010;31(1):36-42. [PubMed ID: 20197256]. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000005.

-

27.

Marcikic M, Vuksic Z, Dumencic B, Matuzalem E, Cacinovic V. Double suicide. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2011;32(3):200-1. [PubMed ID: 21540722]. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e31821a553f.

-

28.

Schwartz AC, Spitalnick JS, Short DK, Garlow SJ. Suicide Pact by Mutual Simultaneous Arm Amputation. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):633-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(09)70867-9.

-

29.

Hunt IM, While D, Windfuhr K, Swinson N, Shaw J, Appleby L, et al. Suicide pacts in the mentally ill: a national clinical survey. Psychiatry Res. 2009;167(1-2):131-8. [PubMed ID: 19342106]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.004.

-

30.

Rastogi P, Nagesh KR. Suicide pact by hanging: a case report. Med Sci Law. 2008;48(3):266-8. [PubMed ID: 18754217].

-

31.

Brown M, Barraclough B. Partners in life and in death: the suicide pact in England and Wales 1988-1992. Psychol Med. 1999;29(6):1299-306. [PubMed ID: 10616936].

-

32.

Durkee T, Hadlaczky G, Westerlund M, Carli V. Internet pathways in suicidality: a review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(10):3938-52. [PubMed ID: 22073021]. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8103938.

-

33.

Dunlop SM, More E, Romer D. Where do youth learn about suicides on the Internet, and what influence does this have on suicidal ideation? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(10):1073-80. [PubMed ID: 21658185]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02416.x.

-

34.

Ruder TD, Hatch GM, Ampanozi G, Thali MJ, Fischer N. Suicide announcement on Facebook. Crisis. 2011;32(5):280-2. [PubMed ID: 21940257]. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000086.

-

35.

Mancinelli I, Comparelli A, Girardi P, Tatarelli R. Mass suicide: historical and psychodynamic considerations. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(1):91-100. [PubMed ID: 11931014].

-

36.

Mancinelli I, Comparelli A, Girardi P, Tatarelli R. Mass suicide: a possible interpretive model. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45(8):765. [PubMed ID: 11086566].

-

37.

Jauhar: mass suicide by self-immolation in Waco, Texas. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182(12):727-8. [PubMed ID: 7989922].

-

38.

Takahashi Y. Mass suicide by members of the Japanese Friend of the Truth Church. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1989;19(3):289-96. [PubMed ID: 2799880].

-

39.

Robbins T. Religious mass suicide before Jonestown: the Russian Old Believers. Sociol Anal. 1986;47(1):1-20. [PubMed ID: 11618195].

-

40.

Das A. Farmers' suicide in India: implications for public mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(1):21-9. [PubMed ID: 21252353]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010103645.

-

41.

Behere PB, Behere AP. Farmers' suicide in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra state: A myth or reality? Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50(2):124-7. [PubMed ID: 19742218]. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.42401.

-

42.

Rezaeian M. Suicide clusters: introducing a novel type of categorization. Violence Vict. 2012;27(1):125-32. [PubMed ID: 22455189].

-

43.

Rezaeian M. The concept of disease clustering for public health specialists. Middle East J Family Med. 2009;7:25-7.

-

44.

Rezaeian M, Dunn G, St Leger S, Appleby L. Geographical epidemiology, spatial analysis and geographical information systems: a multidisciplinary glossary. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(2):98-102. [PubMed ID: 17234866]. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.043117.

-

45.

Johansson L, Lindqvist P, Eriksson A. Teenage suicide cluster formation and contagion: implications for primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:32. [PubMed ID: 16707009]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-7-32.

-

46.

Haw CM. A cluster of suicides at a London psychiatric unit. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24(3):256-66. [PubMed ID: 7825198].

-

47.

Gould MS, Wallenstein S, Kleinman M. Time-space clustering of teenage suicide. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(1):71-8. [PubMed ID: 2293755].

-

48.

Gould MS, Wallenstein S, Davidson L. Suicide clusters: a critical review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1989;19(1):17-29. [PubMed ID: 2652386].

-

49.

Jones JH, Mesoudi A. The Cultural Dynamics of Copycat Suicide. Plos One. 2009;4(9):7252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007252.

-

50.

Joiner JR, Thomas E. The Clustering and Contagion of Suicide. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1999;8(3):89-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00021.

-

51.

Hawton K, Harriss L, Simkin S, Juszczak E, Appleby L, McDonnell R, et al. Effect of death of Diana, princess of Wales on suicide and deliberate self-harm. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:463-6. [PubMed ID: 11060002].

-

52.

Yip PS, Fu KW, Yang KC, Ip BY, Chan CL, Chen EY, et al. The effects of a celebrity suicide on suicide rates in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord. 2006;93(1-3):245-52. [PubMed ID: 16697047]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.015.

-

53.

Ramadas S, Kuttichira P. The development of a guideline and its impact on the media reporting of suicide. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(3):224-8. [PubMed ID: 22135440]. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.86812.

-

54.

Shneidman E. Classification of suicidal phenomena. Bulletin Suicidol. 1968;2:1-9.

-

55.

Beck AT, Davis JH, Frederick CJ, Perlin S, Pokorny AD, Schulman RE. Classification and nomenclature. In: Resnick HL, Hawthorne BC, editors. Suicide prevention in the seventies. USA: Government Printing Office; 1973. p. 7-21.

-

56.

Platt S, Bille Brahe U, Kerkhof A, Schmidtke A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, et al. Parasiticide in Europe: the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1992;85(2):97-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01451.x.

-

57.

Silverman MM. The language of suicidology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(5):519-32. [PubMed ID: 17087631]. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.519.

-

58.

Matarazzo BB, Clemans TA, Silverman MM, Brenner LA. The self-directed violence classification system and the columbia classification algorithm for suicide assessment: a crosswalk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(3):235-49. [PubMed ID: 23145815]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278x.2012.00131.x.