1. Background

Invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures have increased over the past few decades. The provision of moderate sedation and adequate analgesia has been poorly managed (1, 2). The number of procedural sedation cases outside the operating room has risen due to the increase in these procedures with a limited number of anesthesiologists (3-5). The high demand for these services has led subspecialists such as pediatric intensivists, pediatricians, and emergency physicians to stepping into performing Procedural Sedation and Analgesia (PSA). A prior large cohort study showed no difference among subspecialties’ serious adverse events for pediatric procedural sedation (6). With the advance in medicine and the complexity of diseases, the patients’ requirements range from painless diagnostic radiology to frightening, unpleasant procedures (7-9). Inadequate sedation may cause unsuccessful procedures and other detrimental effects on both family and patients. Therefore, the sedation providers should be trained in the administration of sedative drugs, implementation of physiologic monitoring, assessment of sedation levels, and management of adverse events (10-14).

Besides, PSA is well recognized in developed countries, although there are limited data in Thailand, especially among pediatric patients. Our center has established the PSA service for hospitalized patients since 2015. To our knowledge, this is the first pediatric PSA service in Thailand. The indications for consultation include children who have a risk or history of difficult sedation, require an urgent procedure, or are requested by a radio-interventionist. A pediatric resident sedates children without the risk of difficult sedation or simple cases (including normal healthy or mild systemic disease cases).

2. Objectives

The objective of this study was to determine the safety and outcome of PSA outside the operating room among hospitalized children.

3. Methods

This study was performed in a tertiary care, academic center. We retrospectively analyzed the chart review of children aged one month to 20 years who underwent PSA performed by intensivists from January 1, 2015, to July 31, 2019. The included patients were children who had a risk or history of difficult sedation, required urgent procedure, or were requested by a radio-interventionist. Intubated patients and children who had the risk of difficult airway management were excluded. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the authors’ center.

Our pediatric sedation team comprised four intensivists and a trained sedation nurse. All the members of the pediatric sedation team needed to satisfy particular pediatric advanced life support certification. The resuscitation and monitoring equipment included bag valve masks, endotracheal tubes, laryngeal mask airways, resuscitation medications, isotonic crystalloids, cuffed blood pressure, and pulse oximetry without capnography. While a physician performed the drug administration, the nurse continuously monitored the vital signs and oxygen saturation. The depth of sedation was assessed by the patient’s level of consciousness and responsiveness. All significant changes in terms of vital signs and complications were reported and documented by using the standardized sedation records. We collected the demographic data variables, type, and the dose of sedative and analgesic medications, past medical history, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification, indications for sedation, the success of procedural sedation, and adverse events. Mild adverse events (mild AE) were defined as patients who developed urticaria, nausea, hypertension, hypersecretion, or oxygen desaturation of less than 95% without bradycardia. Severe Adverse Events (SAE) were defined as one of the following events: Laryngospasm requiring bag-mask ventilation, bradycardia, cardiac arrest, significant desaturation (a value of oxygen desaturation of less than 95% with bradycardia which required positive pressure ventilation), and hypotension.

3.1. Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the study subjects. The chi-square test was used to compare the differences in mild and severe adverse events. Multiple logistic regressions were used to identify independent variables associated with an increase in the odds ratio of experiencing SAE. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

A total of 641 sedations performed by the PSA team were examined from January 2015 to July 2019. Eighty sedations were excluded due to intubation and the risk of a difficult airway. Thus, 561 PSA procedures performed on 395 patients were included in this study. The median age of the patients was 55 months (range: 19 to 122 months), 58.5% (231/395) were male, and 90.5% (508/561) belonged to ASA class III and IV (Table 1). The most common indication of PSA was central venous line access (49%, 275/561). The common sedative medications were fentanyl (68.8%, 368/561), midazolam (65.6%, 368/561), ketamine (55.4%, 311/561), propofol (46.7%, 262/561), chloral hydrate (6.8%, 38/561), dexmedetomidine (2.9%, 16/561), morphine (0.2%, 1/561), and etomidate (0.2%, 1/561). The success rate of the procedure under PSA was 99.3%. The procedure could not be completed successfully in only four children. Three patients failed due to an unsuccessful procedure. One patient failed due to inadequate sedation with a higher dose of medications. The sedation failure occurred in a four-year-old girl who received dexmedetomidine loading infusion of 1 mcg/kg over 15 min, followed by a maintenance infusion of 1 mcg/kg/h, propofol 4.8 mg/kg, and ketamine 2 mg/kg; however, she could not be adequately sedated for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 395 |

| Number of sedations | 561 |

| Gender: Male | 231 (58.5) |

| Age (months) | 55 (19,122) |

| ASA class | |

| I | 12 (2.1) |

| II | 41 (7.3) |

| III | 506 (90.2) |

| IV | 2 (0.4) |

| Procedural area | |

| Pediatrics ward | 323 (57.6) |

| Radiology department | 158 (28.1) |

| Intensive care unit | 66 (11.7) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit | 14 (2.5) |

| Successful procedure | 557 (99.3) |

| Duration of procedure (min) | 30 (20,45) |

| Adverse events | 22 (3.9) |

| Mild AE | 7 (1.2) |

| Serious AE | 15 (2.7) |

| Indications of procedural sedation | |

| Central venous access | 275 (49) |

| U/S guide intervention | 135 (24.1) |

| Bronchoscope | 47 (8.4) |

| Others | 104 (18.5) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse events; Serious AE, serious adverse events

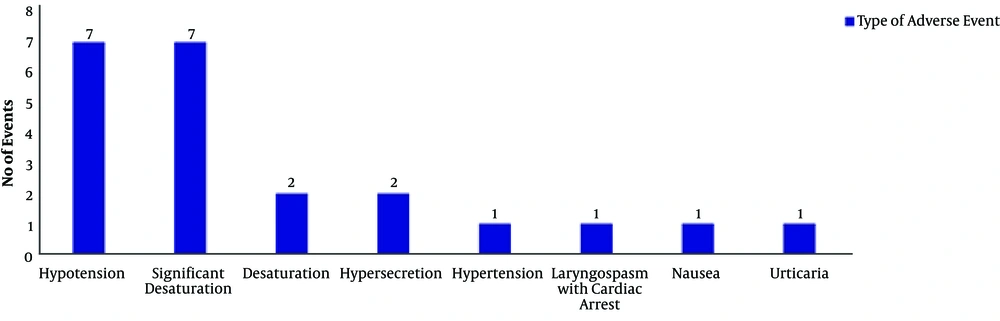

Overall adverse events occurred in 3.9% (22/561), including urticaria, nausea, hypertension, hypersecretion, oxygen desaturation, hypotension, and laryngospasm. Besides, 15 children experienced serious adverse events, including one patient with laryngospasm with cardiac arrest, seven patients with significant desaturation requiring high flow nasal cannula or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, and seven patients with hypotension (Figure 1). The patient with cardiac arrest was a 12-month-old boy with a history of persistent stridor, sedated with midazolam, fentanyl, ketamine, and propofol for a bronchoscopy. A bronchoscope was passed through the nose down into the lung. He experienced laryngospasm and desaturation and required intubation. He received 30 seconds of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and was admitted to the PICU. He was extubated within one hour and discharged home safely in the next two days without any sequelae.

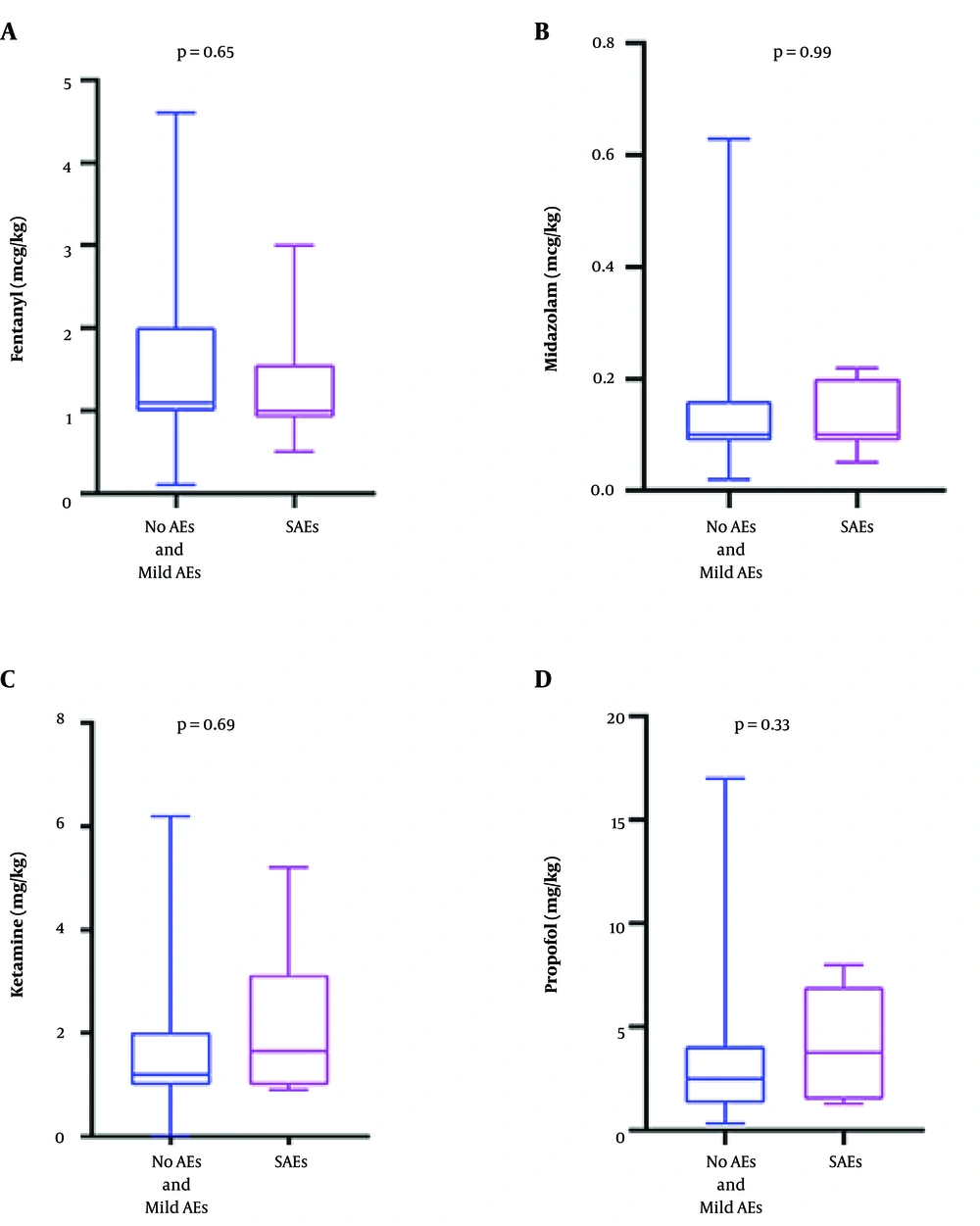

The painless procedure was significantly associated with serious adverse events (P < 0.001). The SAE varied significantly by the location of sedation (P < 0.001). The SAE rate was higher in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). The number of sedative medications was associated with SAE (P = 0.001) (Table 2). The multiple logistic regression analysis, adjusted for clinical variables that were significantly associated with SAE (age, location of sedation, type of procedure, ASA classification, and the number of sedative medications), showed that only patients who received more than three sedative medications had higher SAE than patients who received fewer medications (odds ratio: 8.043; 95% CI: 2.472 - 26.173, P = 0.001). There was no significant difference in weight-based dosing of fentanyl, midazolam, ketamine, and propofol between the two groups (Figure 2).

| Variables | No AE and mild AE (N = 546) | SAEs (N = 15) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 57 (19,112) | 32 (12,160) | 0.713 |

| Gender; male, No. (%) | 306 (56.0) | 8 (53.3) | 0.835 |

| ASA classification | |||

| ASA I-II | 50 (9.1%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.161 |

| ASA III-IV | 496 (90.8%) | 12 (80.0%) | 0.132 |

| Sedation time (min) | 30 (20,45) | 40 (27.5,62.5) | 0.336 |

| Comorbidities | 0.249 | ||

| None | 8 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Hematology and oncology | 219 (40) | 3 (20) | |

| Gastrointestinal and liver disease | 97 (17.8) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Renal system | 64 (11.7) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Respiratory system | 33 (6.0) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Other | 125 (22.9) | 3 (20) | |

| Painful procedure | 463 (84.8) | 9 (60) | < 0.001a |

| Procedure | 0.002a | ||

| Central venous access | 272 (49.8) | 3 (20.0) | |

| U/S guide intervention | 130 (23.8) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Bronchoscope | 42 (7.7) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Other | 102 (18.7) | 2 (13.3) | |

| No. of sedative medication(s) received | 0.001a | ||

| 1 | 56 (10.3) | 1 (6.7) | |

| 2 | 232 (42.5) | 4 (26.7) | |

| 3 | 218 (39.9) | 4 (26.7) | |

| 4 | 40 (7.3) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Location | < 0.001a | ||

| PICU and NICU | 69 (12.6) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Radiology unit | 153 (28.0) | 5 (33.3) | |

| General pediatrics ward | 324 (59.3) | 3 (20.0) |

Abbreviations: PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

aSignificant at the level of 0.05.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates the PSA delivery by pediatric intensivists in an upper-middle-income country. To our knowledge, this is the first study in pediatric PSA in Thai children with high ASA classification. The success rate of pediatric PSA was nearly 100%, with a low rate of complications. The overall AE incidence was 3.9%, and the rate of SAE was only 2.7%. There were no deaths in our study. Moreover, PSA performed by intensivists had the benefit of expanding sedation services and reducing healthcare costs. Our results are consistent with previous studies (15, 16) that described the efficacy of PSA by a well-trained sedation team and a high-quality system of sedation service. Importantly, our sedation team comprised four staff with limited resources available. A recent guideline from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends using an end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor during pediatric PSA (5). However, a systematic review showed no difference in cardiorespiratory adverse events between standard monitoring with and without capnography for emergency department procedural sedation (17). Virtual monitoring devices such as capnography were not mandated in this study. The SAE was successfully treated because of early recognition and prompt intervention, which could be reflective of resuscitation skill and sedation assessment.

Some patients required many sedative medications and multiple doses due to chronic underlying medical/surgical conditions and anxiety to achieve the level of comfort. In addition, some children experienced medical procedures and went through the traumatic stress related to their age and environment (18). The choice of medication for PSA depended on not only intensivists to maintain hemodynamic stability but also their need based on the duration of the procedure and drug sensitization in the children. Serious adverse events occurred, although drugs were administrated as less than the maximum recommended dose. Several studies have reported that adverse events were correlated with the number of drugs used (19, 20). Our study reported that patients who received more than three drugs had SAE eight times higher than patients who received fewer than three sedative drugs.

Painful stimuli were considered to have a protective effect on maintaining respiratory activity during PSA (16). This study demonstrated that painful procedures decreased SAE. We found the SAE rate was high in intensive care units, including PICU and NICU. Most patients with adverse events in the ICU were patients who underwent flexible bronchoscopy. Our center routinely performed pediatric flexible bronchoscopy under sedation by the PSA team in the PICU. It can be explained by significant desaturation related to bronchoscopy that is performed in this location. This is in contrast to a previous study, which reported a higher incidence of AE in pediatric dental offices (16).

Patients with ASA class I and II are considered good candidates for PSA (4, 5, 7). Grunwell et al. (16) reported 72% of the population were ASA class I-II, and showed increasing adverse events among the patients with ASA class III-IV. Furthermore, for patients who had ASA class III-IV, Mallampati class III, or conditions increasing the risk of airway compromise, an anesthesiologist must be present (21). There was a prior study of performing PSA by non-anesthesiologists in adult patients who underwent gastro-endoscopy (22). The study showed no increase in adverse events in patients who had ASA class III. Another study showed no SAE in 29 out of 84 children who had ASA class III-IV and underwent computed tomography under anesthesiologists’ supervision (23). This study showed that PSA could be safely performed without an anesthesiologist on patients with ASA classification of more than 3. In addition, 90% of the patients in this study had ASA class III-IV. It could be expressed that adverse events could not stratify the risk by ASA classification.

5.1. Study Limitations

This study has limitations. First, it was a retrospective study in a single-center with a relatively small sample size. Second, the study did not have an actual protocol for PSA because it included patients with a variety of disorders.

5.2. Conclusion

If a hospital experiences an increasing demand for children undergoing PSA, pediatric intensivists may need to take a role in performing sedation service. Our data suggest that children who undergo procedural sedation outside the operating room conducted by pediatric intensivists are safe and effectively treated. The overall incidence of severe adverse events was low. Receiving four or more sedative medications is an independent risk factor associated with serious adverse events.