1. Context

Ever since the world has been on the brink of an uphill battle against the severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a rough approximation of 2.5 million people has lost their lives due to COVID-19 throughout the world (1, 2). Noteworthy, the mental stress level of medical staff, particularly anesthesiologists and critical care physicians, has been profoundly escalated since the pandemic has begun (3). Hand washing and social distancing are considered among essential strategies in the fight against COVID-19 (4). Besides, COVID-19 has demonstrated a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, from asymptomatic carrier to the development of life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (5). There could be mild hypoxemia not matching the clinical status in some patients with COVID-19, which might rapidly deteriorate to severe hypoxemia (6). In addition, atypical clinical presentations such as cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax have been scarcely recognized in these patients (7).

Most patients recover from SARS-CoV-2 without any specific medical treatment (8); however, almost one in six cases experiences respiratory symptoms and related far-reaching consequences that call for intricate and careful management (9). To date, numerous studies have been conducted globally to discover a feasible, effective treatment. Unfortunately, critically ill and mechanically ventilated patients suffering COVID-19 show an overall higher mortality rate (10-12). Although vaccine development offers a glimmer of hope to end the current appalling pandemic, there is still a lack of definitive therapy, particularly for SARS-CoV-2-induced pneumonia (13). Nonetheless, as a desperate attempt to ameliorate the disease, numerous medications, including glucocorticoids, azithromycin, remdesivir, lopinavir-ritonavir combination, hydroxychloroquine, interferon-beta, IL-6 inhibitor drugs, and favipiravir, have been investigated thoroughly (8, 9, 14). Azithromycin is an almost commonly prescribed macrolide antibiotic that also appears to have some potential benefit in suppressing inflammation and viral replication. The drug was among the initial therapeutic candidates for COVID-19 and has been used exponentially. Whether or not it has a prominent role in SARS-CoV-2 inhibition is a subject of future debate (15, 16).

Both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are members of antimalarial aminoquinolines. Furthermore, hydroxychloroquine is a popular option among disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. These medications can induce retinal toxicity and lengthen the corrected QT (QTc) interval (17). The latter could also occur via taking azithromycin (16). The notion of hydroxychloroquine antiviral efficacy was strengthened amid the pandemic based on some early anecdotal evidence (18-20).

Co-administration of azithromycin with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to boost its therapeutic effect has voiced a genuine concern about provoking lethal adverse cardiac events, such as arrhythmia (9). Several studies share the perspective that azithromycin per se does not have a meaningful association with increased cardiotoxicity (8). In other words, the co-administration mentioned above contributes to high susceptibility to arrhythmia (15).

Given the skepticism around the advantages and disadvantages of these medications, we conducted the present systematic reviews to clarify whether hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin could yield potential health benefits or not. Besides, we evaluated the possibility of adverse cardiac events related to these drugs.

2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

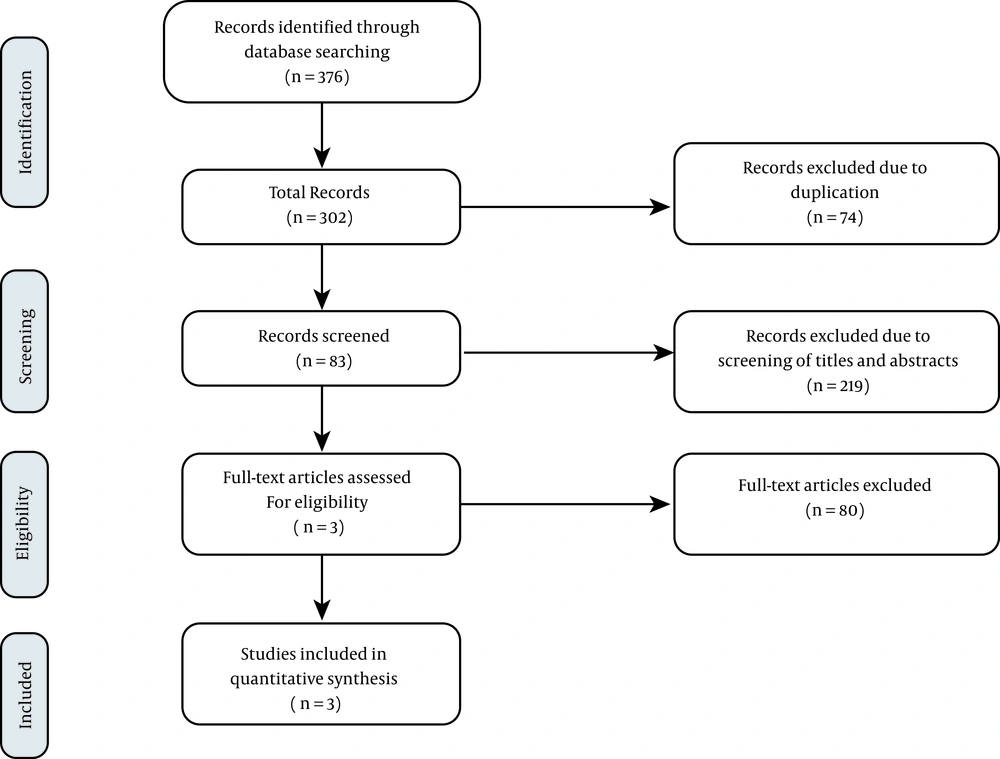

In the present study, we employed an umbrella review approach designed at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences to summarize the results of published systematic reviews that complied with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA). Figure 1 indicates the flow diagram of study selection. To find relevant systematic review articles investigating the association of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without azithromycin on adverse cardiac events and their efficacy, we comprehensively searched PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Embase databases, from January 2020 through November 2020 using the keywords “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” AND “Hydroxychloroquine” OR “Chloroquine” AND “Azithromycin” OR “Zithromax” OR “Azithrocin” AND “Systematic Review”, OR “Meta-analysis”.

2.1. PICO Criteria

- Population: Patients with confirmed COVID-19

- Intervention: Consumption of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without azithromycin

- Comparison: A standard of care

- Outcome: Drug effects

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We merely appraised human-subject studies conducted on patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection who received hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without azithromycin, which comprised assessment indicators with regard to the efficacy and adverse effects of these medications included in systematic review articles alone or systematic review and meta-analyses. Other article types, including case series, letters, duplicate literature, case reports, and narrative reviews, were excluded. Afterward, two investigators (M.G. and K.S.) scrutinized the articles' titles and abstracts independently to determine eligibility. In case of discrepancies, the matter was assigned to a third leading researcher (S.H) to be resolved.

2.3. Data Collection

Two investigators (G.M. and S.K.) screened the full text and quality of articles independently. The extracted basic information included the first author's name, country of study, research purpose, type of studies, number of samples, drug characteristics, drug effect mechanisms, drug side effects, conclusions, and recommendations. Ultimately, the third leading researcher (H.S.) verified the data.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We described the continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation. In order to present categorical variables, we used frequency and percentage.

3. Results

Three studies (systematic review and meta-analysis) were analyzed to evaluate chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine's arrhythmogenic potential with or without azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 and find the clinical efficacy of such a combination (Table 1). The present study examined a total of 62 papers and 43643 cases, including patients with mild pneumonia to critically ill intubated patients.

| Authors | Location | Studies | Samples | Results | Conclusion | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kashour et al. (8) | SaudiArabia+ USA | 19 | 5652 | Pooled incidence | HCQ/CQ monotherapy could result in TdP, VT, and SCA | Using HCQ/CQ as routine management of COVID-19 infection has no justification. If there is another indication for their administration in these patients, monitoring is required. | |

| VT, TdP, SCA | 3 per 1000, 95% CI (0 - 21), I2 = 96% | ||||||

| Discontinuation of CQ/HCQ due to prolonged QTc or arrhythmias | 5%, 95% CI (1 - 11), I2 = 98% | ||||||

| Change in QTc From baseline of ≥ 60 ms or QTc ≥ 500 ms | 9%, 95% CI (3 - 17), I2 = 97% | ||||||

| Changes in QTc from baseline of ≥ 60 ms | 7%, 95% CI (3 - 14), I2 = 94% | ||||||

| QTc ≥ 500 m | 6%, 95% CI (2 - 12), I2 = 95% | ||||||

| 2. Fiolet et al. (9) | France + Switzerland | 29 | 11932 participants for the HCQ group, 8081 for the HCQ with azithromycin group, and 12930 for the control group | Pooled relative risk (95% CI) | HCQ in combination with azithromycin increases the mortality rate of COVID-19 patients. | Not only the combination of HCQ and azithromycin, but also HCQ monotherapy is not recommended for COVID-19. | |

| HCQ alone | 0.83 (0.65-1.06) | ||||||

| HCQ with azithromycin | 1.27 (1.04-1.54) | ||||||

| 3. Mao et al. (21) | China | 14 | 5048 | Effectiveness | There is no evidence supporting the effectiveness of HCQ, CQ, and azithromycin. | Because the observational cohort studies were dominant in this study, large-scale RCTs were recommended. | |

| In-hospital death (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 1.160 [0.430, 3.133] | ||||||

| In-hospital death (HCQ/CQ + azithromycin vs. control group) | 2.332 [1.627, 3.666] | ||||||

| In-hospital death (HCQ/CQ + azithromycin vs. HCQ/CQ) | 1.072 [0.580, 1.978] | ||||||

| Non-detectable viral RNA (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 1.827 [0.390, 8.547] | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 1.434 [0.423, 4.867] | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation(HCQ/CQ + azithromycin vs. control group) | 1.096 [0.126, 9.512] | ||||||

| ICU entry (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 1.199 [0.554, 2.593] | ||||||

| Safety | |||||||

| Adverse drug reactions (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 2.1 [0.458, 9.624] | ||||||

| Diarrhea (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 1.189 [0.338, 4.183] | ||||||

| Abnormal ECG (HCQ/CQ vs. control group) | 4.253 [0.608, 29.769] | ||||||

| QTc prolongation (HCQ/CQ + azithromycin vs HCQ/CQ) | 1.382 [0.582, 3.278] | ||||||

General Characteristics and Results of eligible Studies

4. Discussion

Azithromycin is mainly associated with gastrointestinal adverse reactions (22). Of note, it can extend the duration of action-potential and cardiac repolarization via blocking the delayed rectifier potassium channels (IKr), which can intensify the risk of developing ventricular tachyarrhythmia such as torsades de point (TdP) (23). Generally, hydroxychloroquine has been favored over chloroquine due to having less tendency to produce cardiotoxicity. Given the structural similarity between aminoquinolines and class IA antiarrhythmic drugs, QTc prolongation is likely to happen following their usage (18). In the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies suggested that hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin concurrent use could lead to a marked decline in the viral load (24). Afterward, it became evident that the upshot of taking hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without azithromycin is highly controversial (25).

Kashour et al. analyzed 19 studies, including 5,652 cases with COVID-19 infection, to anticipate potential cardiotoxicity related to chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine monotherapy led to TdP, VT, and sudden cardiac arrest with an incidence of about three per 1000 (95% CI, 0 - 21%). The treatment was discontinued in approximately 5% of patients due to QTc prolongation or cardiac arrhythmia. However, up to 9% experienced marked QTc prolongation (QTc ≥ 500 ms or QTc change ≥ 60 ms). Factors including age, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, ICU admission, concomitant use of QTc-prolonging drugs such as azithromycin, and the severity of the disease were responsible for heterogeneous findings in these studies. Taken together, their routine use, aside from randomized clinical trials, has no justification in treating COVID-19 patients (8).

Fiolet et al. conducted a systematic review of 29 studies, including 32,943 cases. They found that hydroxychloroquine was not statistically significantly related to the mortality of COVID-19 patients (relative risk (RR) = 0.83 with 95% CI = 0.65 to 1.06), and it had no meaningful therapeutic efficacy, as well. Besides, the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin elevated the mortality rate of COVID-19 patients (RR = 1.09 with 95% CI = 0.97 to 1.24) (9).

Mao et al. analyzed 14 articles, including 5,048 patients treated with aminoquinolines alone or in combination with azithromycin. They found neither positive clinical outcomes nor drug-related adverse critical cardiac events in comparison with control groups (21).

All in all, we found no benefit for patients with COVID-19 who received hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin during the current pandemic. Moreover, it is of paramount importance that these medications affect cardiac repolarization, resulting in both statistically and clinically elevated risk of notorious arrhythmias, such as TdP, especially in critically ill patients.

In conclusion, it appears that there is no way to derive a real benefit from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without azithromycin in the setting of COVID-19. It is also noteworthy that these therapeutic strategies could inflict irreparable harm on these patients.

4.1. Recommendations

Our country's current guideline has recommended hydroxychloroquine as an outpatient treatment for high-risk patients with no definitive indication for hospitalization, especially when experiencing early symptoms. Therefore, we humbly offer to take these findings into account while updating the guideline. Due to the increased risk of mortality, there is no place for the combination of hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin during the management of COVID-19 patients. We recommend not to use hydroxychloroquine monotherapy in patients with COVID-19 infection due to the significant risk of cardiac adverse events without any conspicuous clinical efficacy.