1. Context

Tracheal intubation is a clinical procedure to place a flexible tube into the trachea with the aim of keeping a safe airway and establishing ventilation. Some circumstances may require intubation, such as loss of consciousness, major surgeries, decreased oxygen saturation (hypoxemia), airway obstruction (laryngospasm), or respiratory diseases, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (1, 2). Because intubation is an invasive and uncomfortable procedure, it is often performed under general anesthesia and using a neuromuscular-blocking medication.

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, because infected patients develop acute respiratory distress and respiratory failure, putting invasive airways can prevent the disease progression (1-3). Almost 14 - 30% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients develop a respiratory failure at different degrees (moderate to severe) and may need intensive care (4-6) so that less than 5% of COVID-19 patients required intubation and invasive ventilation at some stages of respiratory failure (7). The need for intubation and mechanical ventilation in cases who are critically ill is vary ranging from 30 to 100% (8).

Currently, different statistics are provided on the intubation rate of COVID-19 patients in intensive care units (ICUs). On March 4, 2020, 3.2% of infected cases in China required intubation (7). Also, in a study conducted in New York, 12.2 to 33.1% of COVID-19 patients needed intubation (4, 9). The duration of intubation is different for each patient. Wali et al. examined the course of five COVID-19 patients who needed invasive oxygen therapy (10). It was found that most patients were intubated in the first 2 days of admission. The duration of ventilation with an endotracheal tube was between 4 and 30 days. Intubation can be due to various reasons, like decreased oxygen saturation, respiratory distress, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (11). In this situation, intubation at the right time is very important, and delayed intubation can cause patients' death (12). Xiao Lu showed that mortality in intubated patients with COVID-19 is higher than in patients who were not intubated (13). Most intubations are performed in the ICUs. According to recent studies, more than 10% of COVID-19 patients in northern Italy who suffered from hypoxia were intubated in the ICU (14). It is reported that old age, diabetes mellitus, respiratory rate, increased level of C-reactive protein, bicarbonate level, and oxygen saturation are the most valuable predictors of the need for mechanical ventilation (15). One of the distinguishing characteristics of hypoxia in COVID-19 patients is “the happy hypoxic”, which means that the patient is mentally alert and there is no significant respiratory distress, but low blood oxygen saturation can be developed (16). These patients are at high risk of rapid status deterioration without any signal; thus, they should be under close monitoring, and preemptive action should be taken into account (17).

The timing of intubation, as well as the making decision to perform endotracheal intubation, may be unique for COVID-19 patients case by case (18). The threshold for intubation may be lower in COVID-19 because the use of high-flow nasal oxygen (2) or supposedly noninvasive ventilation can increase the risk of disease transmission to healthcare providers. Therefore, early, controlled intubation may also increase the safety zone of intubation through enough preparation time for this high-risk procedure. The application of airborne precautions is highly recommended throughout … (19, 20). The most serious clinical characteristics of respiratory insufficiency in patients with COVID-19 are hypoxemia and increased breathing (tachypnea). To avoid oxygen toxicity in oxygen therapy, patients should be monitored closely in the ICUs (21). Due to the involvement of the alveoli in COVID-19 pneumonia, it is vital to deliver oxygen at the right concentration to maintain oxygen saturation and avoid decreased partial pressure of oxygen.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly contagious respiratory disease. Many treatments have been used to prevent and treat this disease. However, simple solutions, such as mild exercise (22), hand washing, and social distance (23) are effective in preventing and even treating COVID-19. Yet, there is no known cure other than vaccines (as prophylactic agents). Despite all the clinical experiences, protocols presented, and extensive research, COVID-19 patient management is still an extremely challenging issue (particularly critically ill patients). Therefore, along with completing information about the pathophysiology of this disease, therapeutic interventions for critically ill patients might be the standard care and proper and primary diagnosis and treatment (24). Health care providers, particularly anesthesia and ICU physicians experience mental stress and anxiety. This mental stress could be worsened with the fear of disease transmission and contamination (25).

2. Methods

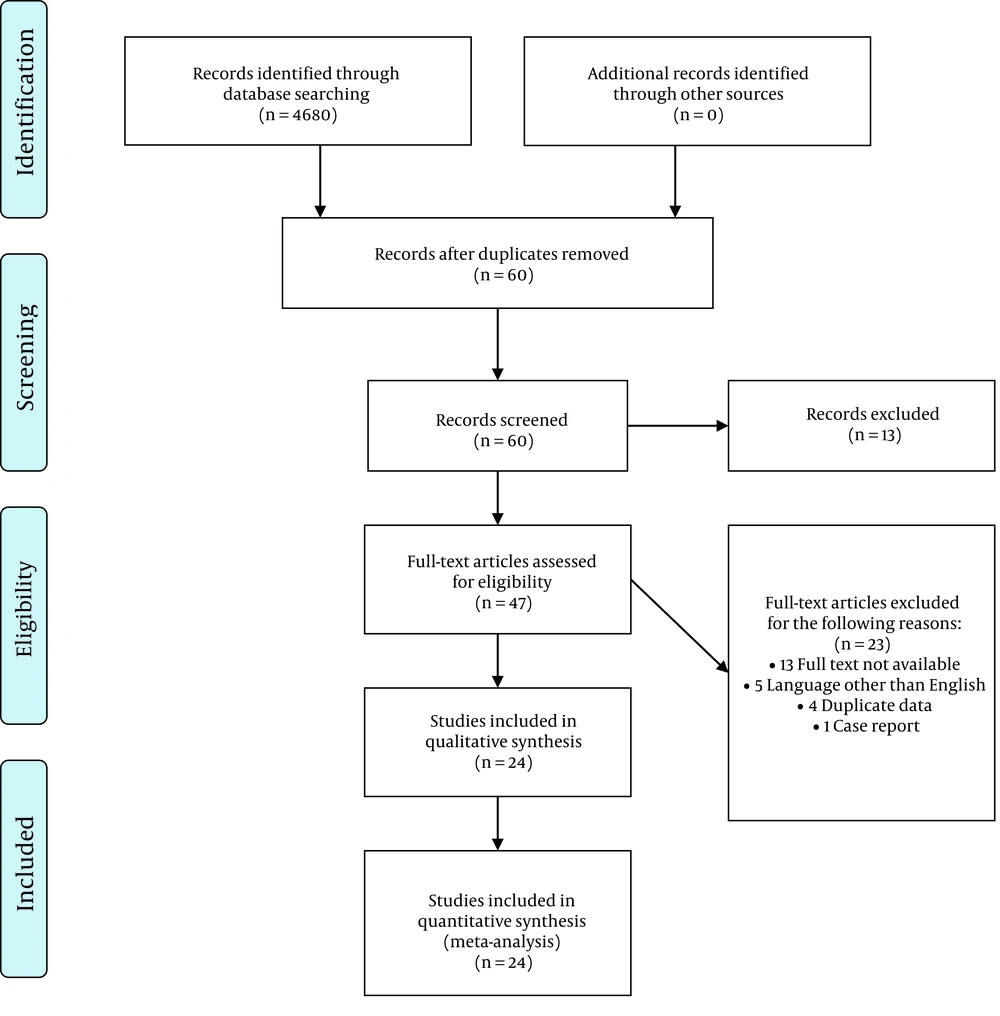

The literature search to identify articles on intubation statistics and COVID- 19 was conducted using the PubMed, Embase, and Scopus databases on April 1, 2021. The publication time was limited to 2020 onward. A total of 4,680 papers were identified by the initial search (Figure 1). Three independent reviewers assessed the abstracts and full texts. The inclusion criterion was studies presenting the percentage of COVID-19 patients (not all patients) who required endotracheal intubation. Reports regarding intubation in COVID19 patients presenting the rate of intubation were included in this review. The study was limited to the papers written in the English language. Exclusion criteria were non-English papers, papers on non-human subjects, case reports, and case series with less than 10 patients. The main question of this review was how many patients infected with COVID-19 were intubated? And what are the associated factors?

This study was approved by the Internal Ethical Committee of Critical Care, Imam Khomeini Hospital (IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1399.389).

3. Results

Overall, 24 studies regarding the intubation rate in COVID-19 patients were included in the final analysis (Tables 1 and 2). Most of the patients had been intubated in the ICU. Studies had been conducted in the USA, Spain, Italy, China, South Korea, Brazil, and Iran.

| References | Sex | Age | Ward | Extubation Rate (%) | Intubation Rate (%) | Cause (s) of Intubation | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (26) | 210 Male patients, 128 Female patients | 39 (IQR 31- 45) | ED | _ | 8 % (28 out of 338) | Respiratory failure | USA |

| (27) | 78 patients (Not specified) | 58.4 ± 13.7 | ICU | _ | 12.82 % (10 out of 78) | Respiratory failure | Iran |

| (28) | 60 % Male, 40 % Female | 59 | ED | _ | 13 % | Long-term Hypoxia | USA |

| (29) | Mostly Male | 50 - 81 | Oncology | _ | 5 % | Hypoxia and Lung injury caused by decreased oxygen | USA |

| (30) | Mostly Male | 47 -70 | Infectious disease | _ | 26.7 % | Hypoxia | USA |

| (31) | 52 % (53/102) Male, 48% (49/102) Female | 68 (IQR 61-75) | ICU | _ | 57% women (59 out of 102) | Hypoxic respiratory failure | USA |

| (32) | 78 % (83/108) Male, 22 % (25/183) Female | 64 (IQR 57-70) | ICU | 12/822 (1.4%) | 20 % (163 out of 822) | _ | Italy |

| (33) | 137 (71%) Male patients | 60 ± 13.8 | _ | _ | 62.7 % | _ | USA |

| (34) | 90 (53%) Male patients | 57 ± 11 | ICU | _ | 38.29 % | _ | USA |

| (35) | 53(33%) Male patients | 62 ± 14.3 | ICU | _ | _ | ARDS | USA |

| (36) | 35 (67%) Male patients, 17 (33%) Female patients | 59·7 ± 13·3 | ICU | _ | 42 % (22 out of 52) | ARDS | China |

| (5) | 1304 Male patients, 287 Female patients | 63 (IQR 56 – 70) | ICU | _ | 88 % (1150 out of 1591) | Hypoxia and ARDS | Italy |

| (37) | 49% Male: PE group, 45% Male: non-PE group | 62 ± 16 PE group, 59 ± 15 non-PE group | ICU | _ | 65 % in Pulmonary Embolism patients, 67 % in the non- Pulmonary Embolism patients | Hypoxia and PE | (37) |

| (38) | No data available | No data available | ICU | 44.5% (842 out of 1890) | 16.4 % (1890 out of 11493) | - | Spain |

| (13) | 9 Male patients, 7 Female patients | 58 (IQR,47 – 68) | ICU | - | 56.25 % (9 out of 16) | Respiratory failure | China |

| (39) | No data available | No data available | ICU | - | 41.20 % (82 out of 199) | Acute respiratory failure | Spain |

| (40) | 28 Male patients, 19 Female patients | 70 years (IQR, 63 - 77) | ICU | - | 48.9 % (23 out of 47) (early intubationa), 34 % (16 out of 47) (late intubationb) | ARDS | South Korea |

| (41) | 88 Male patients, 50 Female patients | 55 cases ≤ 60 years, 83 > 60 years | ED, ICU, and other wards | 56.5 % (78 out of 138) | 24.8 % (138 out of 486) | Decreased oxygen saturation, Shortness of breath | USA |

| (9) | 92 Male patients, 38 Female patients | 64.5 years (IQR, 51.7 - 73.6 | _ | 33.1 % (43 out of 130) | 33.1 % (130 out of 393) | Dyspnea | USA |

| (42) | 25 Male patients, 5 Female patients | 65.5 years (IQR, 57 - 71) | _ | 20 % (6 out of 30) | 23.25 % (30 out of 129) | Hypoxemia | USA |

| (43) | No data available | 65 years (IQR, 53 - 77) | Various wards | _ | 10.6 % (467 out of 4389) | Decreased Oxygen saturation, Hypoxia | USA |

| (44) | 37 Male patients, 45 Female patients | No data available | _ | _ | 33.75 % (27 out of 82) | Hypoxia | USA |

| (45) | 112 Male patients, 54 Female patients | 58.1 ± 14.1 | ED | _ | 58 % prone positioning (33 out of 57), 49 % No Prone (53 out of 109) | Hypoxia, tachypnea | Brazil |

| (46) | 129 Male patients, 93 Female patients | 69.5 (IQR, 62 - 78) | Various wards | _ | 41 % Intubation First (91 out of 222), 20 % NIV to intubation (44 out of 222) | ARDS, Hypoxia, Altered Mental Status | USA |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ED, emergency department.

a Early intubation: intubation as soon as ARDS diagnosis.

b Late intubation: not initially intubated, but subsequently required intubation during follow-up.

| First Authors | Year | Study Design | Grade Of Recommendation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toussie D | 2020 | Retrospective study | B | (26) |

| Ansarin K | 2020 | Randomized clinical trial | A | (27) |

| Caputo ND | 2020 | observational cohort study | B | (28) |

| Miyashita H | 2020 | n/a | - | (29) |

| Sinha P | 2020 | Randomized clinical trial | A | (30) |

| Luo J | 2020 | Retrospective study | B | (31) |

| Bartoletti M | 2020 | Prospective study | B | (32) |

| Rojas-Marte G | 2020 | Retrospective study | B | (33) |

| Pereira MR | 2020 | Initial cohort study | B | (34) |

| Chao TN | 2020 | Prospective observational cohort study | B | (35) |

| Sommer P | 2020 | n/a | - | (36) |

| Grasselli G | 2020 | Retrospective case series | C | (5) |

| Poyiadji N | 2020 | Retrospective analysis | B | (37) |

| Martin-Villares C | 2020 | Prospective observational study | C | (38) |

| Lu X, Zhang M | 2020 | Prospective observational study | C | (13) |

| Ferrando C | 2020 | Adjusted cohort study | B | (39) |

| Lee YH | 2020 | Retrospective Study | B | (40) |

| Hur K | 2020 | Retrospective observational study | C | (41) |

| Goyal P | 2020 | retrospective case series | C | (9) |

| Mughal MS | 2020 | Retrospective study | B | (42) |

| Nadkarni GN | 2020 | Retrospective analysis | B | (43) |

| Barlass U | 2020 | Cohort study | B | (44) |

| Padrão EM | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | B | (45) |

| Daniel P | 2020 | Retrospective study | B | (46) |

Various statistics of intubation rate in COVID-19 patients are reported ranging from 5 - 88 %. This difference in statistics can be due to differences in sample size, study environment (wards), and intubation criteria (28, 31). Rapid sequence induction (RSI) or modified RSI was mostly used for intubation (47). Propofol was used mostly in all cases and often in combination with other sedative agents, like rocuronium, sufentanil, and midazolam. Studies have shown that factors affecting COVID-19 severity (such as underlying disease, the age of more than 50 years, smoking, body mass index, and comorbidity condition) could exacerbate a patient's condition and accelerate the necessity for endotracheal intubation (29, 31). The most important reasons that require endotracheal intubation are hypoxia, respiratory distress, and loss of consciousness (13, 26, 27). Xu et al. suggested that the most prominent reason for intubation in critically ill patients is the lack of respiratory sufficiency. However, in some cases, airway obstruction (or aspiration) and cardiac insufficiency are the intubation causes (48).

Some studies have revealed that due to the limited capacity of ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic (49), tracheostomy seems to be a suitable solution for patients for weaning from the mechanical ventilation (50), decreasing the respiratory effort in patients with limited pulmonary reserves, reducing the dead space, and enabling the suctioning of accumulated mucous (38).

Despite the rarity of available studies regarding extubation in COVID-19 patients, it has been revealed that the extubation rate ranges from 1.4 % to 44.5% (32, 38).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 was the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. COVID-19 may induce severe respiratory distress. Acute respiratory distress in COVID-19 patients could require endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Proper intubation and management of patients with COVID-19 are integral parts of critically ill patient's management. In confirmation, a study stated that of the patients who died, only ~ 25% received invasive mechanical ventilation (intubated) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (51). It seems that the lack of a ventilator or delayed intubation may be one of the causes of deterioration disease in COVID-19 patients.

It has been suggested that (52), less than a third of patients with COVID-19, may benefit from high-flow nasal cannula therapy, noninvasive ventilation, and awake prone position. Patients who have extubated can also benefit from this treatment strategy. The use of awake prone positioning as a supplement therapy to high-flow nasal oxygen therapy did not reduce the risk of intubation and mechanical ventilation (53). However, it could cause delayed in intubation (39). It seems that there are no significant differences in mortality rate between the early intubation group and never intubated patients (40).

According to the necessity of intubation, specialists suggested the use of esophageal manometry (as a surrogate of pleural pressure) and considering intubation when pressure swings exceed 15 cm H2O indicating the risk of self-inflicted lung injury (54). Based on experience-based recommendations, once the patient's noninvasive ventilation failed, elective intubation should be preferred to minimize clinical risks, such as contamination of medical staff (55). Adequate application of personal protective equipment can reduce the risk of nosocomial infections for proceduralists (56). It is recommended that healthcare providers be committed to hand hygiene, airborne precautions, and donning personal protective equipment (57), particularly in airway management circumstances. It is worth noting that in cases where patients need an emergency tracheostomy, utilizing personal protection equipment, such as fit-tested N95 respirator, face shields, and double gloving, can reduce the risk of contamination (58).

Several factors are associated with intubation in COVID-19 patients. Elderly patients, male patients, and those with background diseases, particularly hypertension and diabetes, are more at risk of intubation (1, 15, 35, 56). Also, chest CT scan and respiratory rate are important prognostic factors in determining the severity of the disease and overall prognosis (59). Increased levels of ferritin, d-dimer, and lipase in common with hypoxia are correlated with intubation and ICU admission (42, 44). It was found that anticoagulation use is associated with lower intubation (43). Pulmonary embolism and cardiac tamponade are two complications of COVID-19 patients at the time of ICU admission. If proper emergency management initiates, the patient's life might be saved (60). ROX index is a noninvasive and outstanding predictor for the necessity of intubation in COVID-19 patients (61). The ROX index is the ratio of oxygen saturation that is measured by pulse oximetry. The fraction of inspired oxygen to respiratory rate is a feasible tool as a predictor of the need to intubate in patients who received high flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (62).

In terms of difficult airway management, the upper airway nerve block method may be proper for tracheal stenosis patients who are rigid bronchoscopy candidates (63). Also, it is suggested that video laryngoscopy in comparison to direct laryngoscopy can provide better visualization for intubation of the trachea in congenital heart disease. However, it needs time and a well-trained expert (64). In children with tongue trauma, a flexible laryngeal mask airway is more appropriate in comparison to the endotracheal tube because it reduces extubation time, recovery period, and hemodynamic changes to the airway control (65).

Although appropriate positioning is an essential part of successful intubation, awake-prone positioning may not be correlated with intubation rates (45). Furthermore, there was no significant change in terms of PaO2 before prone positioning and after resupination (66).

It seems that noninvasive ventilation (NIV) may have survival benefits so that patients who received NIV have lower mortality than patients who did not receive NIV and were intubated (46). Solaimanzadeh suggested that some calcium channel blocker agents, like nifedipine and amlodipine, may remarkably meliorate mortality and reduce the risk of intubation and the need for mechanical ventilation in elder COVID-19 patients (67).

The intubation rate has been reported to be 5 to 88 %. In a review study by da Silva et al., intubation need vary from 42% to 47% (68). Besides, Cardona et al. reported that the intubation rate was 28% among hypoxic COVID-19 patients (69). This discrepancy in statistics may be due to the variety of study populations, study environments, or intubation criteria. However, there are a few pieces of evidence regarding extubation; therefore, more investigations are required to determine intubation outcomes and extubation. Obesity and old age are the only risk factors of delayed or difficult extubation (41).

In terms of mortality of the patients undergoing subsequent intubation, it was reported to be vary from 15.2% (41), 23.1% (27), 24.5% (4), to 36.0% (70). Hernandez-Romieu et al. (53) found no association between time to intubation and mortality of infected patients. However, regarding non-COVID-19 ICU mortality, mortality during intubation-related and the overall ICU mortality rate in intubated patients were 1% and 30%, respectively (71).

Due to the lack of definitive treatment for COVID-19, and the research-based empirical treatments, it seems that a comprehensive intubation algorithm in COVID-19 patients is extensively required (71).

We reviewed the intubation rates based on previous studies. These statistics are preliminary and more studies are needed to examine factors affecting the intubation of patients and the correlation between them.

4.1. Limitations

This narrative review design of the study limited our preference for the intubation rate of COVID-19 patients. Therefore, selection bias is possible. Also, causality relationships between disease severity and intubation and extubation might be neglected. This review was limited to English language papers possibly leading to missing some valuable manuscripts in other languages.

4.2. Recommendations

According to studies and reported experiences, we hereby provide some experienced and evidence-based recommendations that can improve the quality of care: 1) Utilizing personal protective equipment to prevent transmission; 2) It is better than the most experienced specialist intubates patients; 3) Noninvasive ventilation may correct oxygenation and is associated with survival benefits. It can be considered for patients who tolerate it; Rapid sequence induction in combination with video laryngoscopy enabled swift intubation (36); Necessary equipment should be available prior to intubation procedure (monitoring, intravenous access, resuscitator medications, ventilator, and suction) (53); and considering calcium channel blocker agents (particularly nifedipine and amlodipine) for hypertensive patients (if applicable) (67).