1. Background

The prevalence of obesity as a significant public health problem is increasing worldwide (1-3). Today various medical and surgical treatments are used to lose weight, and the number of patients with obesity undergoing bariatric or non-bariatric surgery is increasing annually. Obesity predisposes to various perioperative complications and changes in the respiratory system that eventually lead to increased airway resistance, decreased compliance, and impaired gas exchange (4). In anesthetized patients, functional residual capacity (FRC), partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), and pulmonary compliance are inversely related to body mass index (BMI) (5). Finally, intraoperative respiratory changes can lead to postoperative complications, longer hospital stays, and mortality (6).

The traditional ventilation method in bariatric surgery is the volume-controlled ventilation (VCV) mode. The main disadvantage of this mode is increased airway pressure due to reduced compliance and increased resistance, potentially increasing the risk of lung barotrauma (7). Pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) can be used in these patients as an alternative. The maximum airway pressure is limited in this mode, so the amount of tidal volume (TV) and minute ventilation is variable (8). Some studies have shown that the PCV mode can improve arterial and tissue oxygenation and increase alveolar recruitment (7-10). The optimal method of ventilation in these patients has not yet been determined. We compared ventilation effectiveness with PCV and VCV modes in patients with obesity undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Given the benefits of the PCV mode, we hypothesized that its use in these patients could improve gas exchange and improve the mechanical variables of the respiratory system.

2. Methods

This study is a prospective randomized open-label crossover trial with a per-protocol design in a university teaching hospital. The study protocol, data collection tool, and informed consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1398.150). Also, the study was registered in the Iranian registry for clinical trials (IRCT20121107011398N14).

Study cases were screened from patients candidate for laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Inclusion criteria were as follows: BMI > 40 kg/m2, age over 18 years, no severe pulmonary disease (according to a clinical exam and the results of spirometry), and no advanced cardiovascular disease (functional class I and no abnormal echocardiographic and electrocardiographic findings). Exclusion criteria were as follows: Patient refusal, inability to maintain ventilator settings for 15 min, failure to maintain a proper ET-CO2 (30 - 40 mmHg), and change of laparoscopic surgery to laparotomy.

2.1. Randomization and Intervention

After taking informed consent, patients were divided into two groups using a random number table extracted from the computer. The study groups were group 1 (VC-PC) and group 2 (PC-VC). After anesthesia induction and endotracheal intubation in the VC-PC group, the patient was ventilated by VCV, which continued for 15 min after blowing CO2 in the abdomen and starting surgery. Then, the ventilation mode changed to PCV until the end of the surgery. The PCV was initiated in group 2 (PC-VC) and then switched to VCV 15 min after pneumoperitoneum. Anesthetic monitoring included standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors. The supine position with 25 degrees of head-up was used for all patients during the procedure. After 3 min preoxygenation with 100% oxygen and administration of premedication (2 µg/kg of fentanyl and 15 µg/kg of midazolam based on total body weight (TBW)), rapid-sequence induction of anesthesia was performed using intravenous propofol 1.5 - 2 mg/kg based on ideal body weight (IBW) and succinylcholine 1 mg/kg based on TBW. Tracheal intubation was performed using an appropriately sized PVC endotracheal tube. For the maintenance of anesthesia, an infusion of propofol at a dose of 100 µg/kg/min of IBW plus 0.6% of isoflurane was used. We adjusted the dose of these drugs using BIS monitoring (BISPECTRAL VISTA system, COVIDIEN, USA) and kept it in the range of 40 - 60. To provide analgesia and muscle relaxation, fentanyl 50 µg/h and atracurium 10 mg/30 min were repeated. An EDP-Neptune ventilator (MEDEK) was used for intraoperative ventilation. A tidal volume of 6 - 8 mL/kg was calculated for both modes of ventilation based on IBW. Then, patients were ventilated during VCV as follows: RR = 12/min, PEEP = 5 cm H2O, and FiO2 = 80% (80% O2 + 20% Air). The Respiratory Rate (RR) was adjusted every 5 min to optimum ET-CO2 (30 - 40 mmHg). In the PCV mode, patients were initially ventilated with P-Peak = 20 cmH2O, RR = 12/min, FiO2 = 80%, and PEEP = 5 cmH2O to reach the ideal TV (8 cc/kg). The airway pressure was adjusted at 2 cmH2O every 2 min until the maximum airway pressure of 40 cmH2O. The RR was adjusted to reach the optimal ET-CO2. The intra-abdominal pressure of CO2 in all patients was 15 cmH2O, which was gradually increased to 19 cm, if necessary. The formulas to calculate the IBW were: 50 + 0.91 [height (cm) - 152.4] for men and 45.5 + 0.91 [height (cm) - 152.4)] for women. All patients received intravenous crystalloid fluids according to the standard protocol, and the rate was adjusted to obtain an appropriate urinary output of 1 cc/kg/h.

2.2. Outcome Variables

The primary outcome of the study was peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) and dynamic compliance of the respiratory system, and secondary outcomes were expiratory TV, mean airway pressure, RR, oxygen saturation (SPO2), heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and ET-CO2, all of which were recorded every 5 min during the intervention period. Also, at the end of 15 min, an arterial blood gas analysis was done. The results were finally recorded in a given form, and the amount of PaO2/FiO2 ratio, dead space volume, D (A-a) O2 gradient, and PaCO2-ETCO2 were calculated and recorded.

If PIP remained higher than 40 cmH2O after 10 min of abdominal insufflation despite the changes in the ventilator setting, it indicated ventilation failure by any of the methods used, and the patient were excluded from further study. With increasing RR up to 20/min in the presence of suitable TV and ET-CO2 still above 40, the ventilation mode was terminated, and the next mode was initiated.

2.3. Sample Size

According to previous studies, with standard VC ventilation in bariatric operations, the mean value for the primary outcome (PIP) was about 28 ± 3.8 cmH2O. Assuming a 20% decrease in this value by PC ventilation as significant, a power analysis was performed using an online calculator available from the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada) by setting alpha at 0.05 and beta at 80%. Regarding the crossover nature of the study, a group of 26 people was calculated (13 patients in each group). Finally, 40 people were studied (20 patients in each group) to increase the accuracy and study power.

2.4. Data Analysis

The obtained data were analyzed by SPSS statistical software version 25. Quantitative findings were reported as mean and standard deviation, and qualitative findings as frequency and percentage. For intra-group and between-group comparisons, appropriate statistical tests such as t test, paired t test, repeated measures, and chi-square were used depending on the type of variable (parametric and non-parametric and normal distribution). A P value of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

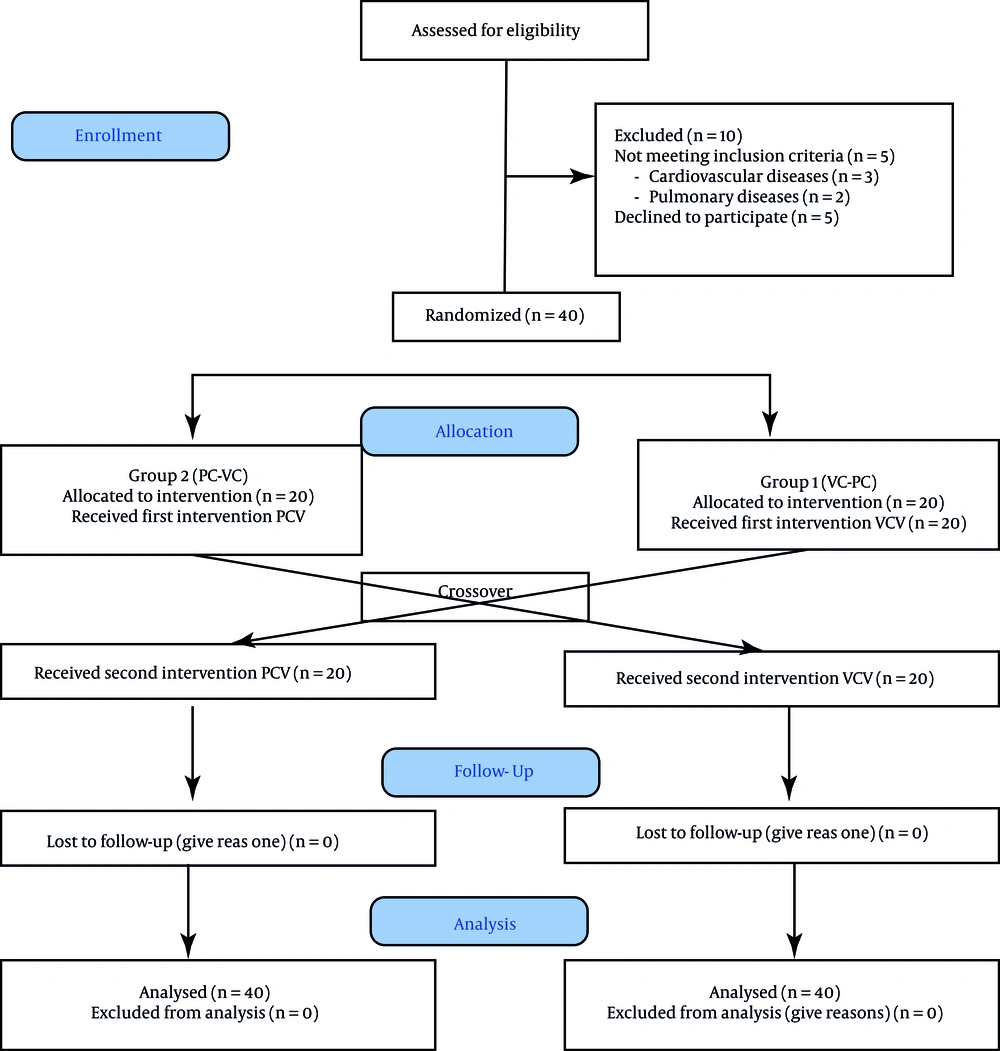

A total of 50 patients were screened for enrollment. After excluding 10 patients (Figure 1), 40 patients were assigned to the two study groups. Sleeve surgery was the most commonly offered surgery performed in 33 patients (82.5%). Demographic data are listed in Table 1. The mean intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) during surgery was 15.07 for PCV and 15.1 cmH2O for VCV, which were not found to be significantly different; also, the hemodynamic profile (MAP and HR) was comparable between the PCV and VCV groups (Table 2).

| Variables | Number | Mean ± SD | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 40 | 35.13 ± 9.06 | |

| Gender (female/male) | 40 | - | 28/12 |

| Weight (kg) | 40 | 129.11 ± 23.54 | |

| Height (cm) | 40 | 164.85 ± 8.64 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 40 | 47.29 ± 5.74 | |

| IBW (kg) | 40 | 59.63 ± 9.21 | |

| Underlying disease (no/yes) | 40 | - | 18/22 |

| Type of surgery (sleeve/bypass) | 40 | - | 33/7 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IBW, ideal body weight.

| Variables | Case No. | VCV | PCV | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP (mmHg) | 40 | 94.19 ± 19.15 | 93.64 ± 20.5 | 0.08 |

| HR (beat/min) | 40 | 83.51 ± 11.7 | 84.48 ± 12.4 | 0.076 |

| RR (cycle/min) | 40 | 14.55 ± 2.82 | 14.84 ± 2.92 | 0.25 |

| IAP (cmH2O) | 40 | 15.1 | 15.07 | 0.09 |

Abbreviations: VCV, volume-controlled ventilation; PCV, pressure-controlled ventilation; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; IAP, intra-abdominal pressure.

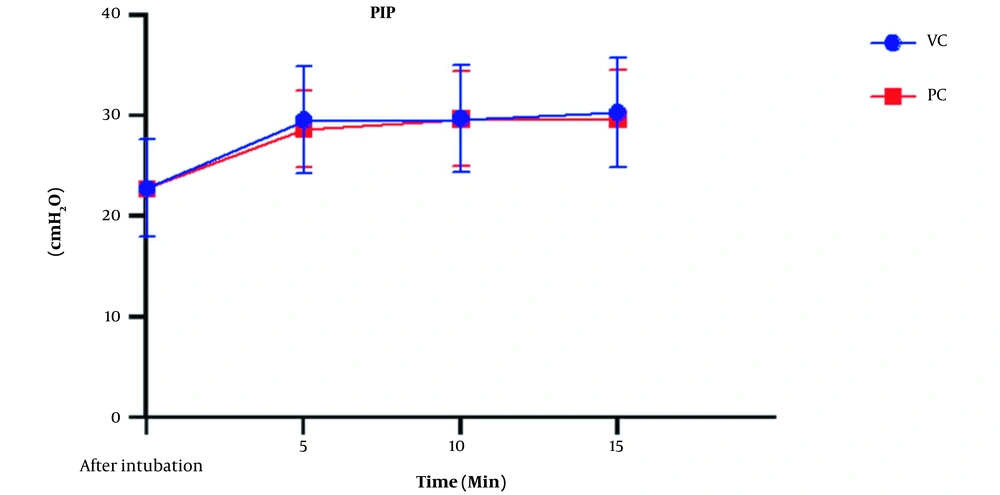

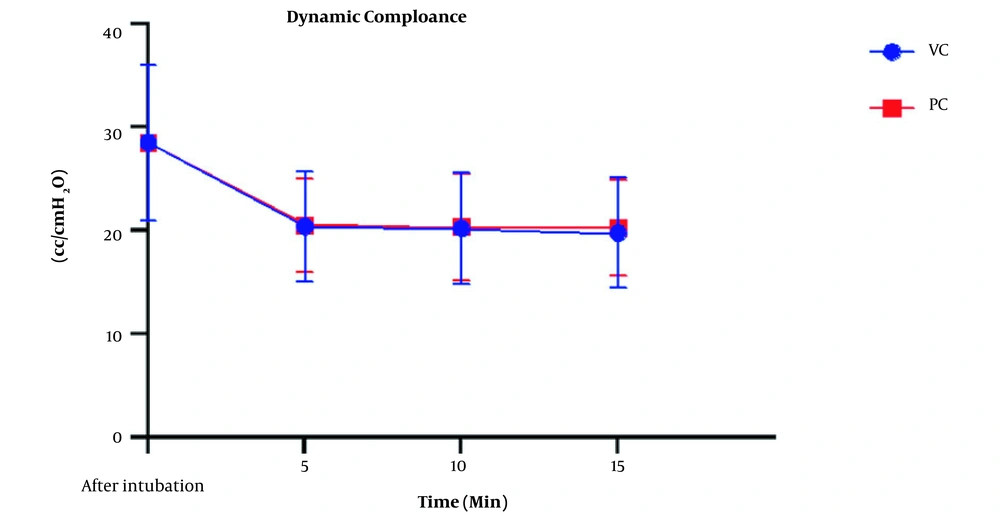

The peak airway pressure was compared, as shown in Figure 2. Airway pressure increased in both types of ventilation with insufflation of CO2 into the abdominal cavity. The ANOVA test showed a significant intra-group increase of this variable (P < 0.001); however, this difference was not significant between the VCV and PCV groups (P = 078). The mean dynamic compliance was 28.55 ± 7.54 cc/cmH2O before pneumoperitoneum but decreased to 20.15 ± 5.36 in the VCV group and 20.43 ± 4.77 in the PCV group after pneumoperitoneum. This decrease was significant in both groups compared to the baseline (P < 0.001), but there was no statistically significant difference between the two types of ventilation (P = 0.92) (Figure 3). Expiratory tidal volumes were 482.25 ± 67.2 and 483.02 ± 69.6 cc during VCV and PCV, which did not differ significantly (P = 0.812), almost equivalent to the ideal TV calculated for patients.

Comparison of ET-CO2 levels using Mann-Whitney U and One-way ANOVA tests showed that with the onset of pneumoperitoneum, the mean of this variable increased in both types of ventilation. However, the rate of increase and mean ET-CO2 in the two groups were almost similar (P = 0.274). A comparison of the RR adjusted to maintain ET-CO2 in the ideal range also did not significantly differ between the two groups. However, a significant increase in the RR after pneumoperitoneum was needed in both groups (P < 0.001).

The comparison of oxygenation status and analysis of arterial gases are summarized in Table 3. No significant difference was found in the mean SPO2, PaO2, PaCO2, and pH between the two groups, where all patients had acceptable oxygenation during surgery. There were no differences in PaO2/FiO2 (P = 0.555) and P (A-a) O2 ratios (P = 0.585) between the two groups. The PaCO2-ETCO2 gradient was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.928).

| Ventilation Mode | Dead Space (mL) | D (a-ET) CO2 (mmHg) | P (A-a) O2 (mmHg) | PH | PaCO2 (mmHg) | PaO2/FiO2 | PaO2 (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCV | 83.95 ± 54.2 | 8.89 ± 6.21 | 253.67 ± 83.5 | 7.32 ± 0.06 | 46.32 ± 7.2 | 229.7 ± 116 | 183.8 ± 92.8 |

| PCV | 90.96 ± 49.85 | 8.76 ± 5.75 | 264.29 ± 79.34 | 7.32 ± 0.05 | 45.08 ± 6.9 | 214.3 ± 102 | 175.1 ± 80.5 |

| P-value | 0.573 | 0.928 | 0.585 | 1 | 0.462 | 0.555 | 0.678 |

Abbreviations: VC, volume control; PC, pressure control; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; PaCO2, partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide; P (A-a) O2, alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient; D (a-ET) CO2, arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide difference.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4. Discussion

This study and our previous one (11), in line with multiple studies (5-7, 12-14), confirmed the undesirable effects of obesity and pneumoperitoneum on gas exchange and mechanical variables of respiration. Oxygenation indices such as PaO2/FiO2 ratio and P (A-a) O2 gradient indicate a right-to-left intrapulmonary shunt, possibly due to decreased pulmonary volumes and atelectasis. Nevertheless, corrective measures such as high FIO2, PEEP, head-up position, and intermittent recruitment maneuvers cannot completely prevent this complication. However, none of the patients suffered from hypoxemia of clinical significance. Furthermore, the dynamic and static compliance was significantly reduced compared to their normal values due to increased airway resistance and intra-abdominal pressure. These changes were present in both PCV and VCV modes.

Although several studies have determined the characteristics of optimal ventilation in these conditions, the desired results have not yet been obtained (14). High TV, which is traditionally common in VCV to maintain PaCO2 levels within the normal range during laparoscopic surgery, causes several complications such as increased airway pressure, volume trauma, and lung inflammation similar to that seen in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Inflammatory mediators of the lungs are also released into the systemic circulation and cause inflammatory damage to distant organs (15). We used low tidal volume (8 cc/kg IBW) to tackle such issues in this study and maintained ET-CO2 at 30 to 40 mm Hg in both groups.

The results showed no significant difference between the two types of mechanical ventilation (VCV and PCV) in terms of oxygenation, ventilation, and mechanical variables of the respiratory system. In addition, the anesthesia profile and hemodynamic conditions did not differ significantly with the change of ventilation mode in the two groups. A review of the majority of previous studies comparing these two ventilation methods in patients with obesity confirms the present study results. In an earlier parallel study conducted in the same center by the authors of this article (11), similar results were obtained by VCV and PCV modes. In the mentioned study, both mechanical ventilation modes were over 95% successful in ventilating patients with obesity. The researchers concluded that the PCV, like VCV, could be used in intraoperative ventilation in patients with obesity. Although the PCV performed better in specific areas such as the PaO2/FiO2 ratio and the volume of respiratory dead space than the VCV, this difference was not statistically significant (11). The only difference between the present study and the previous one is the type of patient allocation to the research groups, parallel versus crossover allocation, to minimize the effect of individual differences of patients in the results.

In a crossover study by Hans et al. on 40 patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, patients were classified into two groups after the first hour of surgery, including VC-PC and PC-VC. In both ventilation periods, patients' PaO2 and PaCO2 did not differ significantly. Therefore, they concluded that PCV mode did not improve gas exchange in patients with obesity compared to VCV, although the maximum inspiratory pressure in PCV ventilation was lower in PCV (16). Aldenkorrt et al. evaluated 13 studies (more than 500 patients) to compare ventilation with VCV and PCV modes and a combination of other interventions such as PEEP and recruitment maneuver in patients with obesity during surgery. They did not find any difference in PIP, oxygenation, and ventilation, but it further affirmed the positive effect of PEEP and recruitment maneuver on patients' oxygenation (17).

Furthermore, a study by Balick-Weber compared the respiratory and hemodynamic effects of ventilation with VCV and PCV modes during laparoscopic surgery, confirming the findings of our study (18). A survey by Movassagi et al. on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy did not report a significant difference between the VCV and PCV modes, consistent with the present study (19). Finally, a meta-analysis published by Cousta Souza et al. reviewed 14 clinical trials with 574 patients. No evidence was found in favor of VCV and PCV ventilation, and both modes could be used in patients with obesity undergoing bariatric surgery without significant complications (20). De Baerdemaeker's study concluded that both VCV and PCV modes were equally suited for laparoscopy procedures in patients with morbid obesity, with CO2 elimination being more efficient when using VCV. These contradictory results may be associated with using a higher TV (10 cc/kg) (9).

In some previous studies, the most critical advantage of PCV ventilation has been the peak inspiratory pressure reduction and, consequently, the lower probability of barotrauma (21, 22). Dion et al. examined 20 patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery and used VCV, PCV, and pressure control-volume guaranteed (PCV-VG) modes; they found that PCV and PCV-VG caused less PIP compared to VCV (23). Our study did not show this difference between the two types of ventilation, which may be due to the use of low TV based on the IBW instead of the actual weight of patients in calculating TV.

Several studies inconsistent with the results of our research have concluded that PCV mode was capable of improving oxygenation in patients with obesity. For example, Gupta et al. showed that PCV was more effective than VCV concerning oxygenation in patients with obesity undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (24). Cadi et al. reported a significant difference in oxygenation between PCV and VCV among patients with morbid obesity undergoing laparoscopic gastric banding surgery (25).

One of the limitations of this study was the lack of evaluation of patients with considerable cardiac and respiratory abnormalities, which could affect the clinical findings of the study. Therefore, these results cannot be generalized to patients with these problems.

4.1. Conclusions

Overall, this study showed no difference in the effectiveness of PCV and VCV for the ventilation of patients with obesity. However, our clinical experience has shown that it is easier to use and adjust the VCV mode because respiratory resistance and compliance during laparoscopic surgery are constantly changing following changes in intra-abdominal pressure. This issue causes a significant change in TV when applying the PCV mode, requiring frequent adjustment of PIP to ensure proper ventilation and prevent hypoventilation.