1. Background

Continuous epidural analgesia is a useful technique, because it has a wide adaptation range and provides prolonged analgesia. This method has been used frequently to control postoperative and chronic pain. Problems associated with long-term epidural analgesia include changes in the analgesia area, decrease in efficacy and catheter-related complications (1-3). However, few reports have evaluated long-term changes in epidural anesthesia in large-size animals (4-6).

Previous animal models in long-term studies had limitations and procedures were relatively invasive; namely, the muscles around the vertebra were separated and the ligamentum flavum or the spine was exposed. Furthermore, the catheter was directly attached with an adhesive to a hole drilled at a surgically exposed vertebra or a fascia near the spine. Such animal models do not reflect clinical challenges of maintaining efficacy of long-term epidural anaesthesia.

2. Objectives

To investigate changes over time after the administration of a local anaesthetic through a long-term epidural catheter, we developed an improved animal model and the catheter tip was allowed to move through the epidural space.

3. Materials and Methods

All protocols were approved in accordance with the principles of laboratory animal care advocated by the animal research committee of Kyoto university (Kyoto, Japan) (revised August 2011; experimental run number R-66-5). Animal care, housing, surgery and humane treatment of laboratory animals were in compliance with the guidelines established by the ministry of education, culture, sports, science and technology, Tokyo, Japan.

3.1. Animals

Animals were six beagle dogs weighing between 8.5 and 11 kg. They were anaesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg).

3.2. Surgical Procedure

After removing the hair and disinfecting the area for general anaesthesia, we made a 10 cm skin incision in the lumbosacral region at the location of spinous process from L7 to S1; the puncture site was one intervertebral space. After puncture, immediately, a skin incision was necessary to fix the mesh subcutaneously. A puncture was made by inserting an epidural needle into the canine epidural space from L7 to S1. This method was confirmed in our pilot study to be a relatively safe and easy epidural catheterization method. To be precise, an 18-gauge Tuohy needle (Epineed; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the epidural space by the hanging drop method. An epidural catheter was advanced 5 cm through the needle, because approximately 5 cm of indwelling catheter is associated with a lower incidence of protrusion or bending (7, 8). The position of catheter was confirmed radiographically with an injection (1.5 mL) of iohexol (Omnipaque 300; Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The tip of the catheter was located in the sixth lumbar (L6) region. The monofilament polypropylene mesh (BardMesh; Bard, Crawley, England, UK) used for reconstruction of tissue defects (9-12) was attached to the catheter near the puncture site with cyanoacrylate adhesive, sutured and secured to the subcutaneous tissue. The peripheral end of the catheter was passed subcutaneously from the puncture site to the neck and connected to a syringe-type disposable infusion pump. Finally, the lumbar skin incision was sutured. The infusion pump was placed in the dog jacket. All dogs received 1.0 mL/h physiologic saline solution via the catheter for 5 weeks.

3.3. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Anesthesia on Motor Function

After catheterization, the motor function of each subject was assessed weekly to evaluate the anesthetic efficacy over a 5-week period. A 2% lidocaine solution was administered at a rate of 2.0 mL/min via the epidural catheter, within 1 minute and it was connected to an infusion pump to prevent a countercurrent microcirculatory blood flow. Next, the duration of knuckling of the hind limbs was observed. Generally, knuckling is defined as the ankle being flexed on the side of calf; in our study, knuckling was defined as dogs placing their top of the foot on the ground during walking. The onset point was the time at which knuckling occurred on either side of the limb; the offset point was the time at which knuckling disappeared in both limbs. This motor function was also evaluated at 1, 2 and 3 weeks after catheterization in all 6 dogs; also, it was evaluated at 4 and 5 weeks in 5 dogs, because one dog was killed at 3rd week post-catheterization for histopathologic examination.

3.4. Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography

On two occasions, computed tomography (CT) was performed to evaluate the spread of lidocaine: first, on the day of catheterization (n = 6) and again at 5th week, immediately before the catheter was removed (n = 5). We injected a contrast medium, iohexol (1.5 mL), via the epidural catheter under general anaesthesia. The spread of contrast medium was determined by counting the number of vertebral body units through a 16-detector low CT scanner (aquilion; toshiba medical systems, Nasu, Japan) (13). The contrast medium on CT images was colored blue by image-editing software (Ziostation; Ziosoft, Tokyo, Japan).

3.5. Histopathology Examination

Histological evaluation was performed on the lumbar vertebra at 3rd and 5th weeks after catheterization. The dog was killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. After perfusion fixation, the fifth to seventh lumbar vertebrae were removed en block, fixed with formalin and embedded in paraffin. The specimens were sectioned axially at the middle of L5 (L5-midpoint) and the cephalad, middle and caudal planes of L6 (L6- cephalad, L6-middle and L6-caudad). The sections were stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin-eosin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO; USA).

3.6. Analysis of the Degree of Inflammation

As histological evaluation of epidural space in our previous study indicated an inflammatory state, peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid from 3 dogs were assessed to examine the degree of inflammation.

3.6.1. Hematologic Test

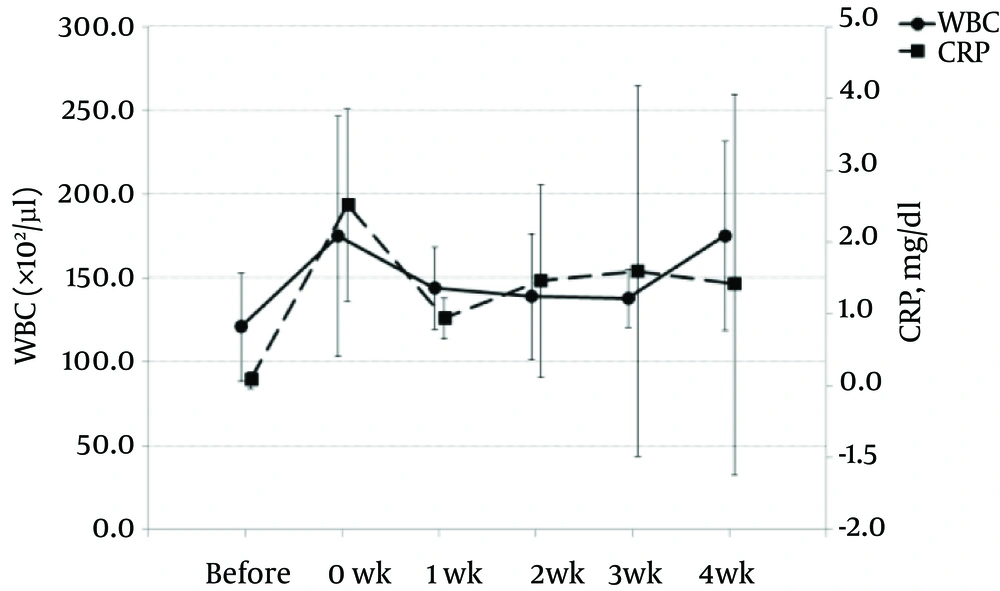

Blood samples were taken from the cephalic vein periodically 1 day before and 4 days after catheterization, and 4 days after each assessment of motor function thereafter. We defined 4 days after catheterization as week 0 in the hematologic test and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling. white blood cell (WBC) count and level of C-reactive protein (CRP) were monitored.

3.6.2. CSF Sampling

After blood sampling on the same day, the cisterna magna suboccipital space was punctured with a 22-G spinal needle (Terumo spinal needle; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan), to obtain 1.0 mL of CSF and the samples were centrifuged. The supernatant was stored at -80°C to assess interleukin 6 (IL-6). We used a canine IL-6 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Quantikine Canine IL-6 ELISA; R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) (14). We considered that a mean minimum detectable value of 6.1 pg/mL (defined by the manufacturer) had negative result for IL-6.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Results of the motor function and hematologic tests are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Dunnett’s test was used to determine differences in motor function compared to that at 1 week and analyze differences in WBC counts and levels of CRP and IL-6 before and after catheterization. Results of CT analysis are expressed as median and range. Differences in the CT analysis between the two groups were analyzed by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Anesthesia on Motor Function

No dog had walking disturbances before epidural anesthesia. The dogs survived uneventfully and did not show any signs of neurological impairment throughout the study period. No catheter-related problems occurred (e.g., reinsertion, refixation or obstruction).

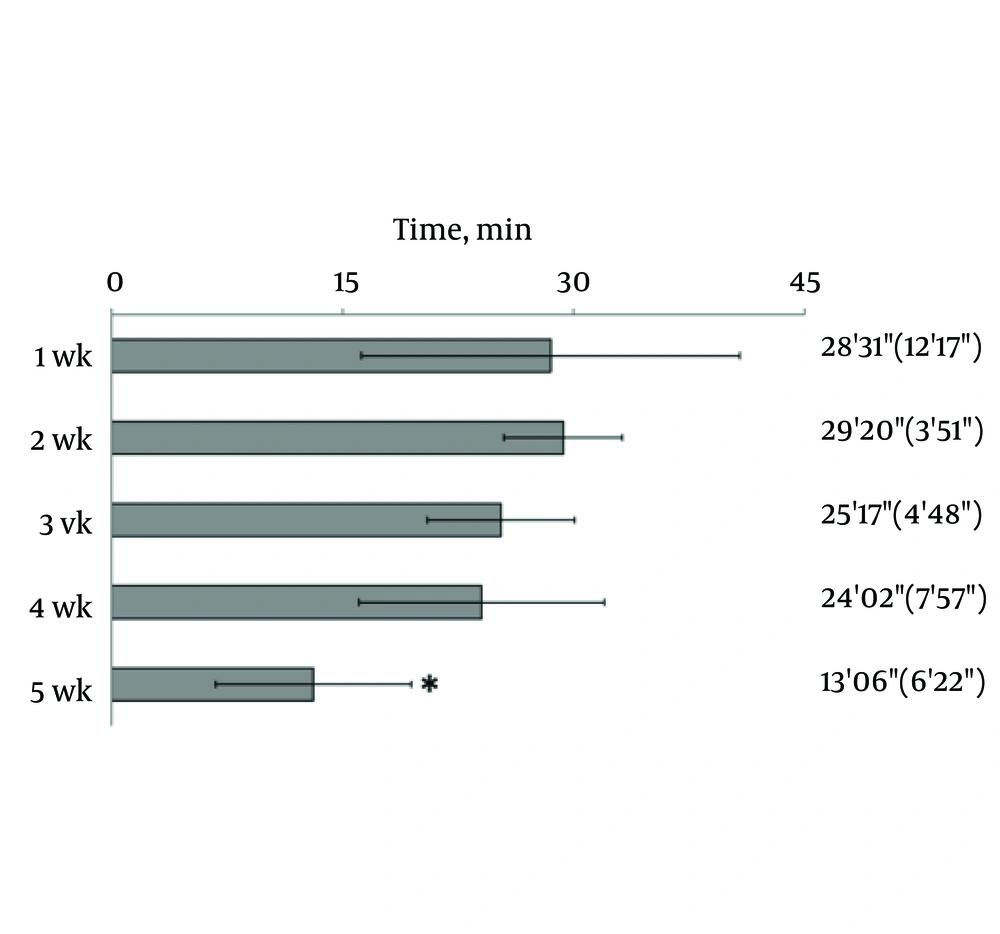

Hind limb knuckling was observed after the epidural administration of 2% lidocaine. Knuckling appeared in one hind limb and then in both limbs; the dogs were unable to support their weight with the hind legs. They recovered in the reverse sequence. The duration of knuckling was significantly reduced at 5th week, compared with the duration of knuckling at the first week (Figure 1).

4.2. Contrast-Enhanced CT

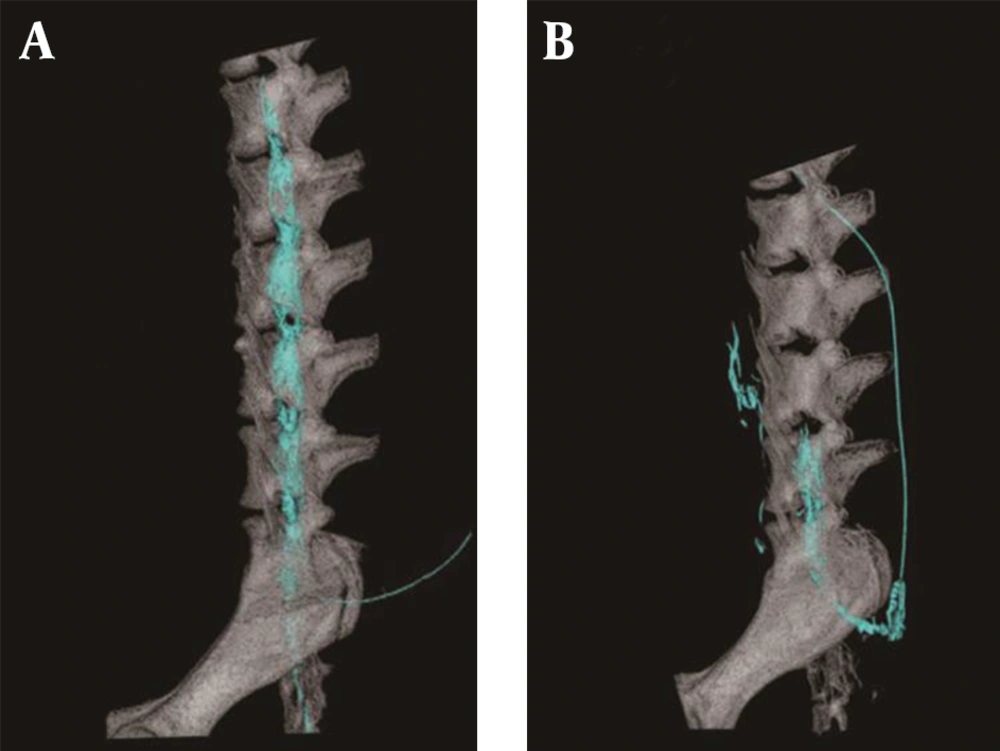

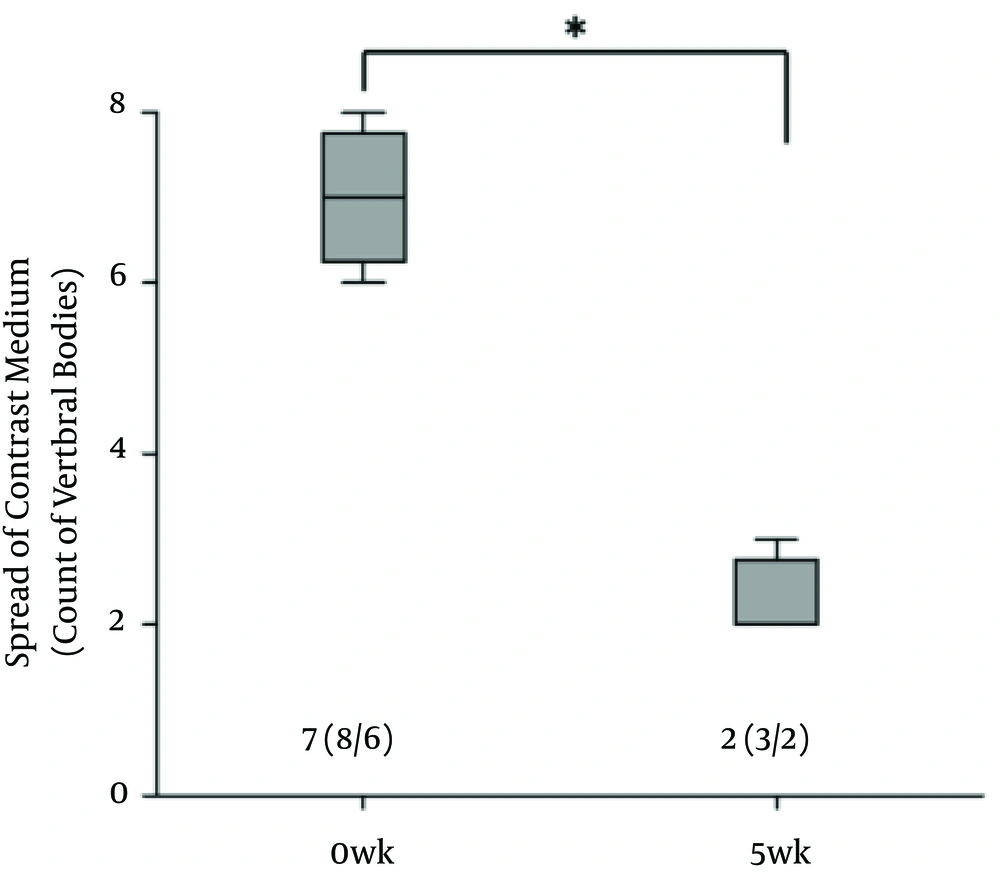

There was no contrast medium above the sixth lumbar region where the epidural catheter tip was located at 5th week. The spread of the contrast medium had extended into the subvertebral space (Figure 2). Radiogram showed that the cephalad spread of the contrast medium was significantly less at 5th week (Figure 3).

4.3. Histopathological Examination

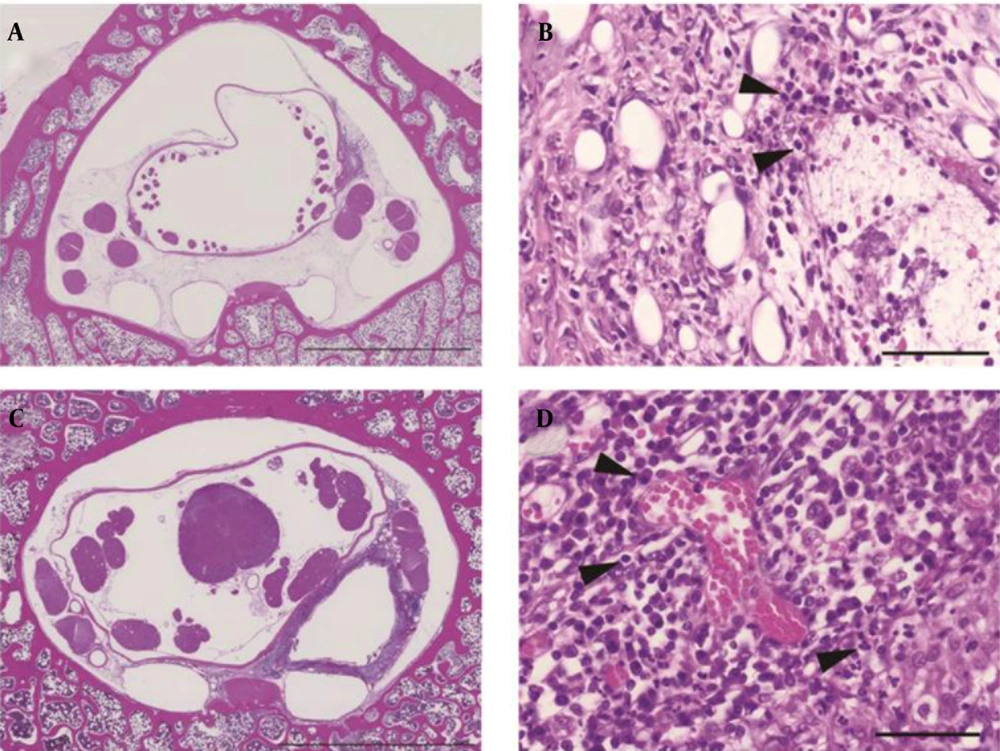

Specimens from L5 at both 3rd and 5th weeks showed accumulation of inflammatory cells in the epidural space. Specimens from L6 showed different histological findings at 3rd and 5th weeks. At 3rd week, small granulation tissue without a tubular construction was present at the L6-cephalad. Granulation tissue surrounded the catheter at the L6-midpoint (Figure 4A) and L6-caudad. The lumen of the granulation tissue was narrow and contained a mass of inflammatory cells. Neutrophils congregated in the layer of the granulation tissue near the catheter (Figure 4B).

At 5th week, circular granulation tissue consisted of annulations of a large lumen in all specimens from L6 (Figure 4C). The lumen extended between the dura mater and the vertebral periosteum. Neutrophils formed the innermost layer around the catheter, lymphocytes surrounded the layer of neutrophils and plasma cells were located in the outer area of the granulation tissue (Figure 4D).

A, L6-midpoint at 3rd week (scale, 5 mm). The lumen of the granulation tissue was narrow. B, L6-midpoint at 3rd week (magnification of granulation tissue layer in A: scale = 50 μm). Capillary angiogenesis and neutrophils were present. C, L6-midpoint at 5th week (scale = 5 mm). The lumen of the granulation tissue was enlarged. D, L6-midpoint at 5th week (magnification of granulation tissue layer in C: scale = 5 μm).

4.4. Analysis of the Degree of Inflammation

4.4.1. Hematologic Test

WBC count and CRP levels were increased slightly at 0 week, the time after catheterization but before administration of 2% lidocaine. Increasing levels of WBC and CRP returned to baseline by 1 week after catheterization (Figure 5).

4.4.2. CSF Sampling

Concentration of IL-6 in the CSF was below detectable limits in the CSF throughout the study period.

5. Discussion

In the current study, the effect of epidural anaesthesia was determined by visual observation of hind limbs after the injection of lidocaine. Knuckling of the hind limb was the primary experimental parameter for measuring the level and duration of epidural anaesthesia. Knuckling involves motor and sensory nerves and results from proprioceptive impairment of the hind limb. The duration of knuckling of the hind limbs at 4th week was approximately 80% of that observed at the first week; by 5th week, the duration of knuckling decreased to half of that observed at the first week. Thus, anesthetic efficacy did not significantly differ from the fourth week.

Results of CT performed immediately before the catheter was removed, showed no contrast medium at the L5 side of the epidural space. Nagaro (4) reported that the contrast medium spread only to the cephalad side of the catheter tip after long-term catheterization. Differences between their report and the present study are the methods of catheterization and fixation and interval of administration. In their report, the epidural catheter was directly attached with cyanoacrylate adhesive to a hole drilled at a surgically exposed vertebra. The catheterization method that required invasive surgery may have induced inflammation. In our study, the catheter was inserted and fixed with minimal tissue damage and minimal hemorrhage. Furthermore, our study fixation method, fixing the catheter on subcutaneous soft tissue with mesh, can replicate catheter movement in the epidural cavity. In a previous report on epidural anaesthesia in dogs, swalander and colleagues fixed the epidural catheter to the skin with suture and butterfly-patterned adhesive tape and could maintain the catheter at the site for 1.85 days (median 2.0 days) (14). In contrast, the present study secured the catheter tip at the targeted epidural space at 5th week, as confirmed by CT. Mesh reinforcement is thought to be an effective method for securing the position and replicating the catheter movement. Moreover, Nagaro (4) intermittently injected lidocaine daily via epidural catheter. Physiologic saline solution was infused continuously for 5 weeks and lidocaine was injected weekly. The difference in inflammation levels around the catheter tip may have been due to the interval of lidocaine administration. The difference in radiological findings between their report and our study may be due to the amount of inflammation caused by differences in the methods of catheterization and catheter fixation and different administration interval.

Tissues around the tip of the catheter were examined at 3 and 5 weeks. Histological evaluation indicated that the catheter tip was capped with fibrotic granulation tissue, which was confirmed by CT. These results suggested that this granulation tissue prevented the contrast medium from spreading over the cephalad and caused leakage of contrast medium from the intervertebral foramen. This similarly suggested that the spread of local anaesthetic administered via the catheter into the epidural space was blocked by granulation tissue. In specimens collected at the 3rd week, there were neutrophils indicative of acute inflammation in the granulation tissue layer. At the 5th week, both acute and chronic inflammation were observed. The formation of granulation tissue is thought to be caused by slight movement of the catheter, foreign-body reaction to the catheter, continuous dosing of saline, chemical stimulation with lidocaine or infection. Furthermore, the specimens of L6 samples collected at the 3rd and 5th weeks suggested that continued inflammation may have led to thickening of the granulation tissue. An inflamed area shows acidic conditions, as demonstrated by a low alkalinity (pH); thus, this widens the gap between the ionization constant (pKa) of lidocaine and the pH of tissue around the catheter. Therefore, the anaesthetic efficacy of lidocaine was reduced. Consequently, we concluded that granulation tissue surrounding the tip of catheter decreased the efficacy of anaesthesia. Suppression of inflammation around the catheter tip to prevent granulation is considered important for successful long-term epidural anesthesia. Previous studies have reported that adding various drugs to the epidural solution can decrease clinical unwanted effects (15-17). Long-term epidural analgesia requires comparative studies with other drug groups.

Evaluation of local inflammation in the epidural space is difficult, especially regarding the craniocaudal direction. The sampling of vein blood and CSF is minimally invasive and repeatable. WBC and CPR increased 4 days after catheterization, but there was no significant difference. WBC count and CRP level recovered to normal levels within one week. This change may have been attributable to the irritation from subcutaneous passage of the catheter. The CSF reflects an inflammatory response in the subarachnoid space and IL-6 in CSF is one of the important indicators of meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage and spinal cord injury (18-22). To our knowledge, no report has measured the IL-6 concentration in CSF after long-term epidural catheterization. The unremarkable level of IL-6 in CSF, coupled with lack of signs in any dog with neurological impairments, may suggest the absence of inflammation in the subarachnoid space. Catheterization produced granulation tissue in the epidural space, but it may have been below the level to induce inflammation in the subarachnoid space. The catheterization and fixation method used in this study seems safe and useful for future studies on long-term epidural catheterization. Furthermore, this study may have followed clinical changes more closely than conventional models since the gradual changes were monitored. To our knowledge, this is the longest study period performed regarding continuous epidural anesthesia in dogs.

The limitations of this study were the small number of subjects and studying only a single group. Although no inflammatory sign was detected in this study, obtaining a bacterial culture of the tip of the catheter is necessary to determine the cause of granulation tissue formation. Further comparative and well-conceived time course studies would be helpful in evaluating optimal methods of suppressing proliferation of granulation tissue.

In conclusion, the efficacy of epidural anaesthesia at 4th week in a canine model using a tuohy needle, monofilament polypropylene mesh and subcutaneous tunneling was fair and did not significantly differ to that at the first week. We speculate that the efficacy of epidural anaesthesia was subsequently limited by the formation of granulation tissue, which capped the catheter tip.