1. Introduction

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) can be defined as "surgical end-stage after one or several operative interventions on the lumbar neuroaxis, indicated to relieve lower back pain, radicular pain, or the combination of both without positive effect (1)." According to available data, failure rates of spinal surgery range from 10% to 40%; therefore, we might assume a reasonable failure rate of around 20%. Clinical presentation is characterized as a chronic pain syndrome invalidating patients for either personal or working way of life. FBSS represents a significant healthcare problem due to the effects on individuals, families, work, careers, healthcare, and other societal costs (1). Typical symptoms associated with FBSS include diffuse, dull, and aching pain, sharp, pricking pain involving the back and legs, and stabbing pain in the extremities due to abnormal sensibility. Moreover, several factors can contribute to the onset or development of FBSS, including but not limited to either residual or recurrent disc herniation, persistent postoperative nerve root pressure, altered joint mobility, axial hypermobility with instability, scar tissue and fibrosis, depression, anxiety, and spinal muscular pain. An individual predisposition to the development of FBSS might be due to systemic disorders such as diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and peripheral vascular diseases (2). Sacroiliac joint pain is more common after spinal fusion surgery, and, on the other hand, internal disc disruption is more frequent in patients with non-fusion surgery (3). The treatments of FBSS include broad therapeutic options such as physical therapy, behavioral medicine, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), minor nerve blocks, and pulsed electromagnetic therapy (4). Pharmacologic treatment is based on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), membrane stabilizers such as pregabalin and gabapentin, antidepressants such as amitriptyline, duloxetine, and venlafaxine, weak opioids such as codeine, hydrocodone, and tramadol (which also has been shown to inhibit reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin), prolonged-release (PR) strong opioids such as morphine, oxycodone (alone or with naloxone), buprenorphine, hydromorphone, and tapentadol, and intrathecal morphine infusion pumps. Recently, the targeted anatomic use of potent anti-inflammatory anti-TNF therapeutics is being investigated (5). One systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in relieving chronic intractable pain of FBSS showed evidence level II-1 or II-2 for clinical use on a long-term basis (6). A recent comprehensive evidence overview concluded that epidural steroid injections for chronic low back pain (CLBP) would provide little, short-term leg-pain relief and improvement in function. Indeed, epidural steroids could be no more effective than injection of local anesthetics alone. Although serious postprocedural complications are uncommon, the risk of contamination and infections could be high in fragile patients (7). Moreover, the US food and drug administration (FDA) has declared the need to include a warning on the rare but serious risks of stroke, loss of vision, paralysis, and death after epidural steroids administration. Therefore, a drug label change for injectable long-term corticosteroids has been recently required (8). In summary, the evidence does not support clinical routine use of off-label epidural steroid injections in adults with benign radicular lumbosacral pain (7). We presented a successful treatment with daily high-dose oxycodone/naloxone (OXN 180/90 mg, Targin Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals, GmbH, Limburg, Germany) in a case of FBSS.

2. Case Presentation

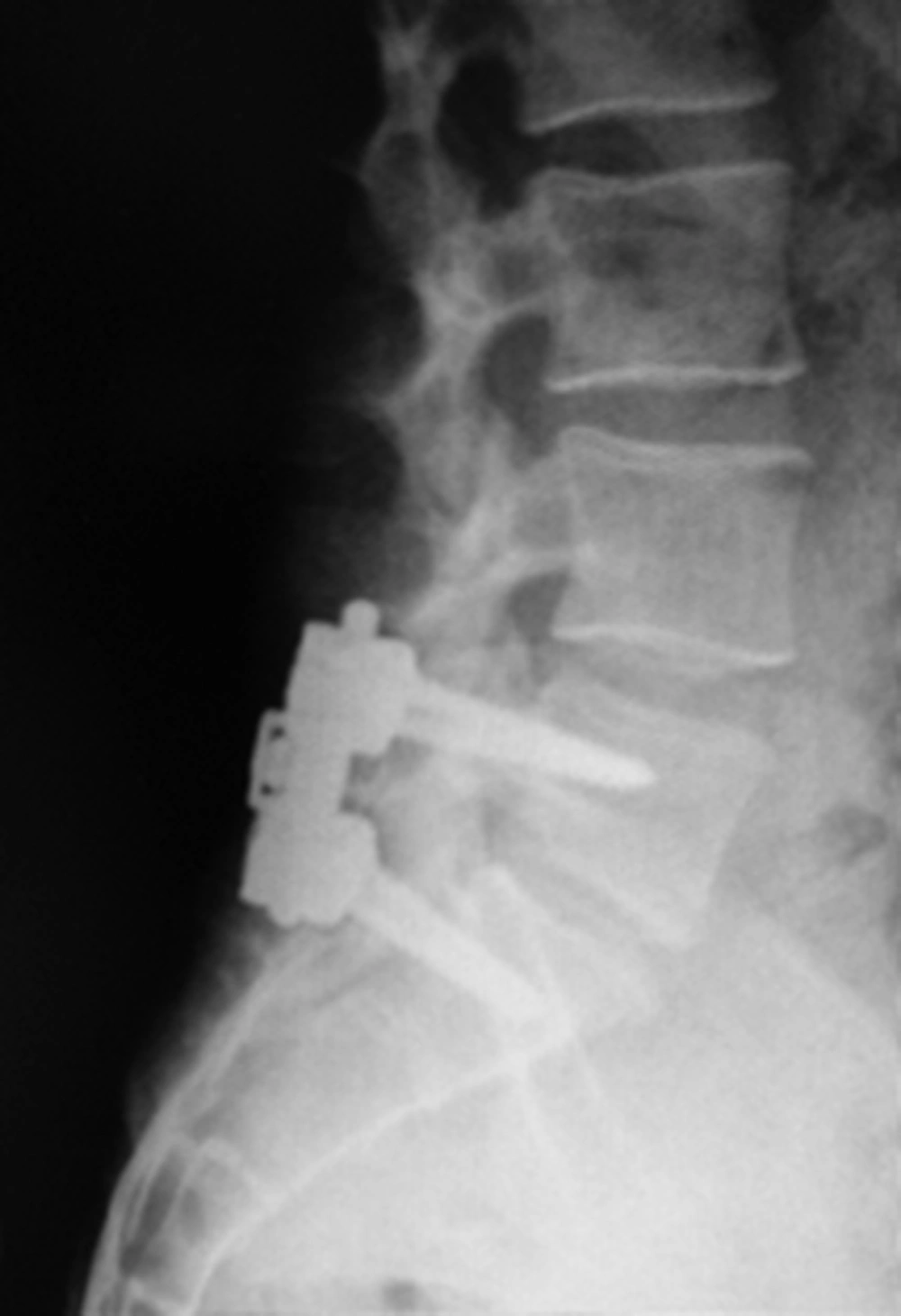

We presented a 43-year-old man, with no previous clinical related disease, which was operated on the back (L5 laminectomy) due to a workplace accident seven years ago. The persistent low back pain led the surgical team to reoperate him two years later, making a spinal arthrodesis L5-S1. After being pain free for six months, he experienced severe pain in the lumbar region again and in left lower extremity (visual analogic scale [VAS], 8). He was re-evaluated by the orthopedic surgeon finding no cause to justify the symptoms after either clinical or radiologic explorations (Figures 1 and 2). Physical rehabilitation program failed to improve patient's condition and therefore, he was sent to the Chronic Pain Unit. The type of pain in this case was described as a mixture of nociceptive and neuropathic pain, but the latter was the main factor detected by the DN4 test (7/10). As a first choice, two caudal steroids injections with 80 mg triamcinolone were carried performed in a three-month period. Pain intensity improved for only a short time, shorter than three weeks after each injection, and unfortunately, the last one produced a local infection that was treated with antibiotics. Due to the potential technical complications, the patient refused caudal epidurolysis. Pulsed radiofrequency was performed on the left L5 dorsal ganglion with also short-term pain relief of shorter than three months. The ganglion was located with the X-ray beam in both posterior-anterior and lateral views and by sensory stimulation (frequency, 50 Hz; pulse width, 1 msec; and voltage, 0.4-0.6 V). Lesion parameters were programmed for preventing temperature exceeding over 42℃, i.e. pulse at 45 V for two cycles of 120 seconds. Although SCS was proposed, the patient failed the psychologic exam due to generalized anxiety disorder and major depression. He was afraid of repeating interventional techniques and selected oral opioid prescription as the best option for himself. TENS was prescribed for low back pain. Medical treatment was based on dexketoprofen (25 mg, TDS), pregabalin (150 mg/d), amitriptyline (75 mg/d), duloxetine (60 mg/d), quetiapine (100 mg/d), and tramadol (400 mg/d) without desirable pain relieve (VAS > 6). Higher dose of pregabalin and amitriptyline were not tolerated well due to severe adverse effects such as dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, and edema. Tramadol was changed into oxycodone but increasing the dose was not tolerated well due to constipation, which was treated with the macrogol (polyethylene glycol) laxative. OXN was initiated as an opioid rotation strategy and the equianalgesic opioid dosing for switching from tramadol to oxycodone (oral-oral) was calculated based on McPherson ML, opioid conversion calculation (120 mg to 20 mg). Good pain control (VAS < 4) was obtained with increasing doses until 40/20 + 20/10 mg each eight hours. With 90 mg naloxone per day, no significant adverse effects were observed during the next twelve months. Immediate release oxycodone (20 mg) was also indicated for breakthrough pain. The Lattinen Index also improved from 17 to 10 points.

3. Discussion

The FBSS obviously needs a multidimensional clinical approach. Therapy failure might result from psychosocial influences, structural abnormalities in the back, or a combination of both. Indeed, causes of back pain are largely unknown and correlations with diagnostic studies are uncertain. This lack of precise diagnosis is reflected into a multiplicity of nonspecific treatments, mostly of unproven value (9). There is limited evidence for oral opioids in the treatment of CLBP; however, their routine use is widespread. Recently, the evidence of short-term efficacy of opioids to treat CLBP in comparison with placebo (little for function and moderate for pain) has been published. Nonetheless, the safety and effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy for treatment of CLBP remains unproven (10). Oxycodone is a semisynthetic thebaine derivative, an opioid of the step 3 World Health Organization analgesic ladders, which binds predominantly to μ and k opioid receptors. Naloxone is a semisynthetic morphine derivative opioid antagonist that acts at μ, k, and δ opioid receptors. Due to very high affinity to opioid receptors, naloxone displaces opioid agonists from the receptors. Hence, it is commonly administered by the parenteral route for the treatment of opioid overdose; however, when given by the oral route, naloxone improves bowel function in patients with opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OIBD) by blocking the oxycodone activation of predominantly μ opioid receptors located in the myenteric and submucosal plexus in the gut (11). Symptoms of OIBD comprise not only opioid-induced constipation (OIC), but also dry mouth, gastroesophageal reflux-related symptoms, nausea, vomiting, bloating, chronic abdominal pain, and constipation-related symptoms including straining, hard stools, painful, incomplete, and infrequent bowel movements. Diarrhea-related symptoms can also be seen, i.e. urgency and loose and frequent bowel movements (12). The oral formulation of OXN consists of PR oxycodone and PR naloxone. Tablets have different strengths: 5/2.5 mg, 10/5 mg, 20/10 mg, and 40/20 mg. The optimal 2:1 ratio of OXN tablets was determined in phase II study, rendering adequate analgesia and improvement in bowel function with good tolerance in patients with severe chronic pain (13). OXN is only approved for the indication of severe pain that might be successfully treated with opioid analgesics only. Orally administered oxycodone displays high bioavailability (60%-87%) and is metabolized primarily in the liver and the intestine wall, mainly to noroxycodone (through CYP3A4) and to a less extent to oxymorphone (via CYP2D6). Oxycodone and its metabolites are excreted in urine and feces (14). Naloxone exhibits low bioavailability (< 3%) after oral administration and undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver, predominantly with the formation of naloxone-3-glucuronide (NAL-3-G). Naloxone and its metabolites are excreted in urine. The efficacy of orally administered naloxone depends on preserved liver function; thus, any hepatic impairment should be carefully considered. Therefore, in patients with liver failure, OXN administration is not recommended (15). The recommended starting doses of OXN in opioid-naive patients are 5/2.5 to 10/5 mg bid. In patients who are not responding to weak opioids (opioids for mild-to-moderate pain such as tramadol and codeine), an initial dose of 10/5 mg or 20/10 mg bid can be usually effective. For moderate to severe pain, if a rotation from other opioids to OXN was needed, the starting dose must be individually established, depending on the amount of previously administered opioid, analgesia, adverse effects, and exhaustive clinical evaluation. The initial dose should be titrated to achieve effective analgesia and acceptable adverse effects. Currently, OXN is approved in daily doses of up to 80/40 mg (16); however, controlled studies in patients with nonmalignant (17) and cancer-related pain (18) demonstrated that the daily dose of 120/60 mg might be safe and effective. On the other hand, Mercadante et al. (19) reported a patient with severe cancer pain, which required high daily doses of OXN (240/120 mg) that were ineffective. Surprisingly, a switch to PR oxycodone alone at a daily dose of 240 mg provided satisfactory analgesia. It might suggest that OXN provides an inferior analgesia in comparison to PR oxycodone given alone at a daily dose of 240 mg due to systemic anti-analgesic action of naloxone. In our case, daily doses of 180/90 mg, divided into three doses due to better drug profile selected by the patient, produced good analgesia without relevant adverse effects probably because of selecting a good young patient with preserved liver function. High-dose oxycodone/naloxone had a better effect on his neuropathic component, specially sharping and pricking pain. Both pain scores and quality of life were improved by the multimodal treatment. Functionality did not improve and patient got total working incapacity. The duration of the prescription is expected to be as short as possible, hoping that psychologic condition would be improved to accept an SCS trial. There were no clear explanations for the better improvement in pain with oral opioids than pulsed radiofrequency. Perhaps nerve roots other than left L5 might be involved in the global lumbar and radicular pain; However, this decision implies long term opioids adverse effects. These high doses of OXN have not been previously reported in literature for successful management of noncancer pain. This clinical setting must be accepted with caution and therefore, a randomized trial should be conducted to confirm this favorable result. While research on FBSS has increased in recent years, the best strategy to reduce incidence and morbidity is to focus on prevention. Consequently, patients diagnosed with FBSS should be managed into a multidisciplinary environment (20). More invasive treatments such as SCS have recently provided clinicians with needed evidence on their effectiveness. PR opioids are a real option when interventional techniques fail or are contraindicated, and OXN can be a proper choice to prevent OIBD, even when high doses of naloxone are used in selected patients, due to an excellent profile efficacy/tolerability. Incorporating these results into our current knowledge would provide the first step in constructing an evidence-based guide to manage patients with FBSS.