1. Introduction

A tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) represents a pathological condition where an abnormal communication between the trachea and the esophagus exists, due to either a congenital or an acquired condition. Congenital TEF is due to an incomplete development of the tracheoesophageal septum occurring between the 4th and 8th week of the embryonic period when there is an abnormal growth of the trachea (1). TEF’s typically present with aspiration of food particles, leading to life-threatening pulmonary complications (2). Causes for acquired TEF’s are multiple, with malignancy and trauma being the most common. Approximately 50% of acquired TEF’s are secondary to mediastinal malignancy (3). Endotracheal tube cuff related trauma contributes to the majority of TEFs in the non-malignant group. The incidence of tracheal erosion as a result of an endotracheal tube in mechanically ventilated patients is 0.3% - 3% (4). Ischemia of the tracheal wall due to increased pressure is a predisposing factor leading to necrosis and the formation of a fistula. The use of high-volume, low-pressure endotracheal cuffs has reduced the incidence of this complication. Other co-existing factors such as poor general state of health, airway infection, episodic hypotension, diabetes, nasogastric tubes and prolonged intubation increases the likelihood of developing an acquired TEF (5). This case describes an elderly female patient with multiple co-morbidities and no previous symptoms, presenting with a TEF in the immediate post-operative period after placement of a tracheostomy. This went unrecognized until advancement of the tracheostomy into the TEF.

2. Case Presentation

A 66-year-old female with a medical history significant for end stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus type-2, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease initially presented to the emergency room with altered mental status. The patient quickly decompensated and suffered a cardiac arrest necessitating advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS). The patient was intubated, received epinephrine 1mg, and calcium chloride 1g, yielding return of spontaneous circulation. In the intensive care unit, labs revealed a potassium level of 8.5 mEq/L, for which she received emergent dialysis. She was extubated on hospital day 4 and transferred to the progressive care unit and started on her routine home medications.

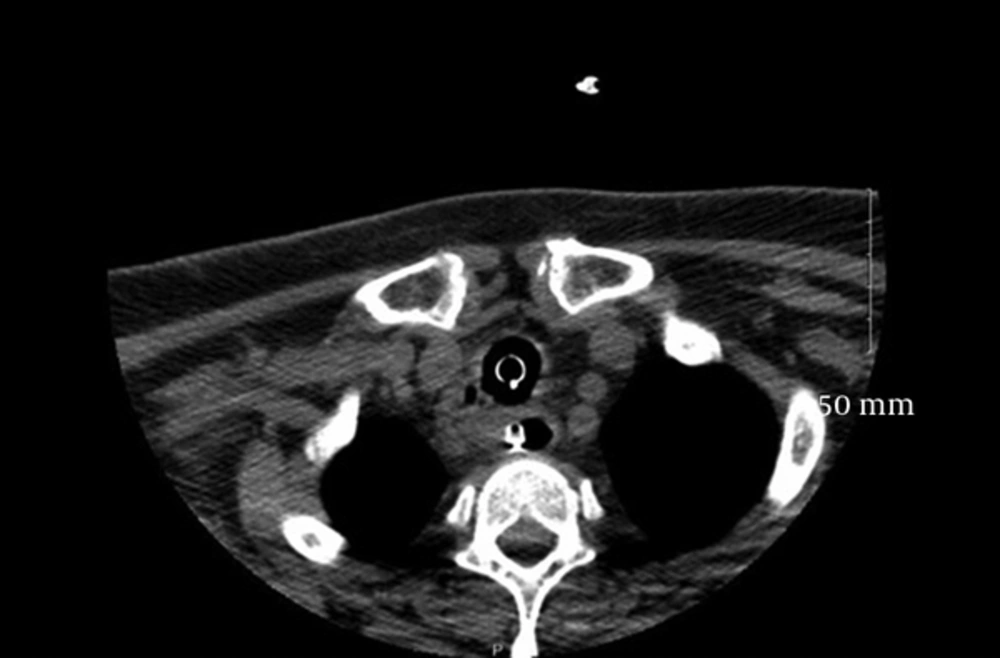

Shortly after being restarted on Lisinopril, the patient complained of shortness of breath, developed stridor, and severe angioedema. Concern of lost airway prompted re-intubation. She was transferred back to the intensive care unit for further medical management. Upon meeting criteria, the patient was extubated on day six, only to be intubated again for stridor. After 9 days of intubation, it was determined that the patient required a tracheostomy. Imaging studies prior to surgery could not rule out subglottic narrowing due to the presence of an endotracheal tube, however, paratracheal edema was noted (Figures 1 and 2). Clinically, her minimal air leak following deflation of the endotracheal tube cuff provided evidence for the latter finding. Intra-operatively, the Otolaryngology (ENT) surgeon noted that the posterior wall of the tracheal mucosa appeared grey and friable. The distal tracheal wall was inflamed and excoriated. The surgery was successful and there were no complications with ventilation in the operating room. Tracheal positioning was confirmed using end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring. The patient was mechanically ventilated in the ICU, but approximately 30 minutes after returning from the OR, mechanical ventilation became difficult. The ventilator sensed an increased airway pressure, and there was distension of the abdomen with each breath delivered. The possibility of a TEF was immediately considered given the friable tracheal mucosa noted in the operating room, and abdominal distention despite the tracheostomy tube being in the trachea. ENT was bedside and confirmed positioning within the trachea by feeling the tracheal rings, and using a fiberoptic scope as multiple attempts to re-intubate from above proved to be difficult. The tracheostomy tube was changed to “extended-length tracheostomy tubes (Shiley ™ XLT) in attempt to bypass a possible TEF, however this also proved to be unsuccessful. The patient desaturated and eventually lost pulses and ACLS was initiated. She was successfully re-intubated following numerous attempts by experienced providers using a combination of gum elastic bougie, video laryngoscopy and fiberoptic larynogosopy. The endotracheal tube was advanced into the right main stem in effort to bypass any TEF. Unfortunately, the patient did not return to spontaneous circulation and was declared deceased at 36 minutes. Permission for an autopsy was denied by the family.

3. Discussion

Prolonged intubation for mechanical ventilation is one of the most common causes of acquired TEF. The time it takes for formation is dependent on the number of precipitating factors involved (5). The patient in this report had several risk factors that predisposed her to the development of a TEF such as prolonged and repeated intubations, diabetes, episodic hypotension, use of nasogastric tube during hospitalization and poor general state of health. In addition to these risk factors, the history of ACE-I induced angioedema may have aggravated her existing risk factors. ACE-I are widely used for the treatment of hypertension, heart failure and prevention of diabetic nephropathy. Angioedema is a rare but potentially serious complication following ACE-I use and the incidence is reported at 0.1% - 0.5% (6). When edema is present at multiple sites and involves the respiratory tract, the result can be fatal (7). In life-threatening scenarios, when patients require intubation, the presence of angioedema of the respiratory tract may lead to difficulty in securing the airway as was seen in this case. The patient subsequently developed subglottic edema. High intra-cuff pressure is probably the most important factor in the development of TEF (8), as high pressures transmitted to the tracheal wall leads to ischemia and necrosis of the tracheal mucosa. The incidence of this complication has decreased with the introduction of the high volume and low pressure cuffs. Intra cuff pressures of > 50 cm of H2O can lead to complete occlusion of tracheal blood flow and in those with hypotension, pressures of 34 cm H2O can lead to tracheal damage (9). It is usually recommended that cuff pressures be less than 20 cm H2O and the cuff volume limited to 6 - 8 mL (10). However, the presence of airway edema as in angioedema may lead to an underestimation of the assessed cuff pressures. Routine measurement of cuff pressure using a manometer can minimize injuries to the trachea.

Acquired TEF usually presents with recurrent respiratory complications, choking or coughing with feeds, positive cuff leak, or gastric distention. The diagnosis of TEF is made by, high resolution CT scan, barium or water soluble esophagography, or endoscopy (11). The evolution of a TEF in a mechanically ventilated patient may be subtle and present acutely as difficulty in mechanical ventilation, drop in oxygen saturation despite perceived adequate ventilation, leak around the cuff and gastric distention. In such cases, an attempt should be made to place the endotracheal tube beyond the fistula. The timeline of the evolution of a TEF varies depending on the precipitating factors and could be obscured if the patient has multiple predisposing conditions. Tracheal intubation for even 10 hours can lead to epithelial disruption and ischemic non inflammatory necrosis, and intubations more than 10 days lead to total disruption of basement membranes and deep ischemic necrosis (12). Repeated ETT manipulations, intubations and excessive head movements further add insult to the tracheal injury (13).

In conclusion, endotracheal tube intra-cuff measurements could have possibly detected on-going ischemic changes in the tracheal mucosa in this case. Emphasis should be placed on daily cuff pressure measurements in the intensive care setting. However, tracheal damage and increased cuff volumes can occur even after maintaining cuff pressures in the acceptable range (14). Also, the development of angioedema may have made the tracheal mucosa more friable, making the patient predisposed to tracheal injury. Bronchoscopic assessment after extubation in patients susceptible to developing a TEF (15-17), is a useful tool that could enable early detection of this devastating complication in mechanically ventilated patients.