1. Introduction

Poor visualization of the larynx leads to difficult tracheal intubation with direct laryngoscopy. When using direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation, the forward flexion of the cervical spine and backward extension of the head at the atlanto-occipital joint is known to align the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes, thereby increasing visualization of the larynx to some extent (1, 2).

In order to facilitate tracheal intubation, several maneuvers such as external laryngeal manipulation, forward cervical flexion and lateral positioning of the patient have been reported (1, 3, 4). Although several studies have reported that the ramped position (torso and head elevated) significantly improves the laryngoscopic view, in our experience, the ramped position fails to provide good laryngeal visualization in some cases. When placing the patient in the lateral position, a rotation of the head, to about 40 degrees, facilitates tracheal intubation (4). We hypothesized that when the ramped position fails to provide good laryngeal visualization, the addition of a head rotation improves laryngeal visualization. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of a patient’s head rotation on laryngeal visualization of patients in the ramped position.

2. Case Report

2.1. The Study Protocol

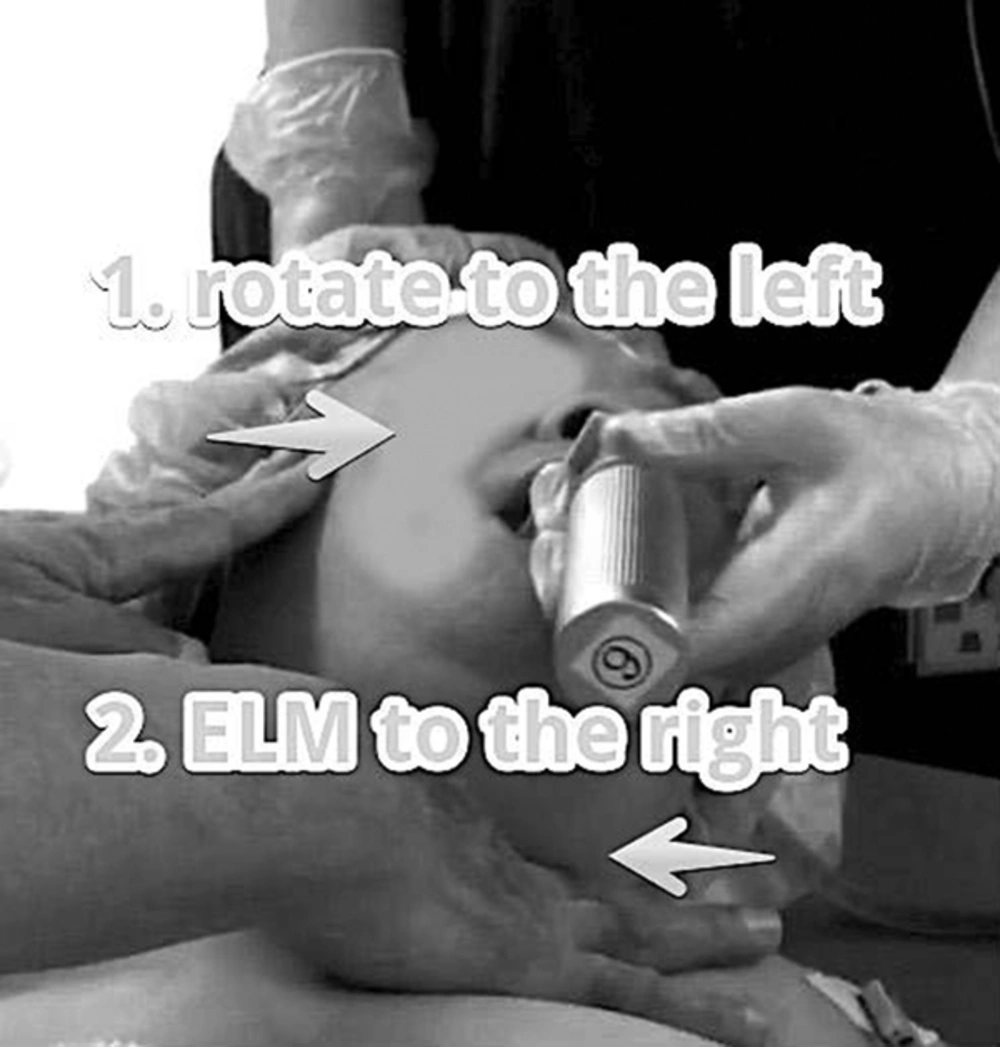

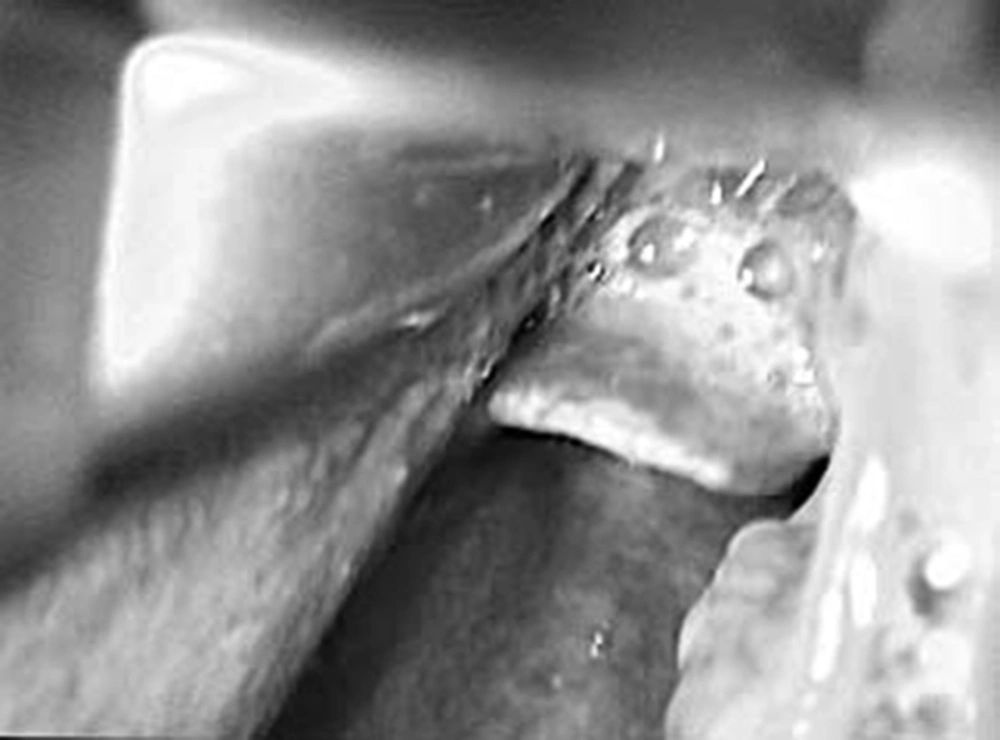

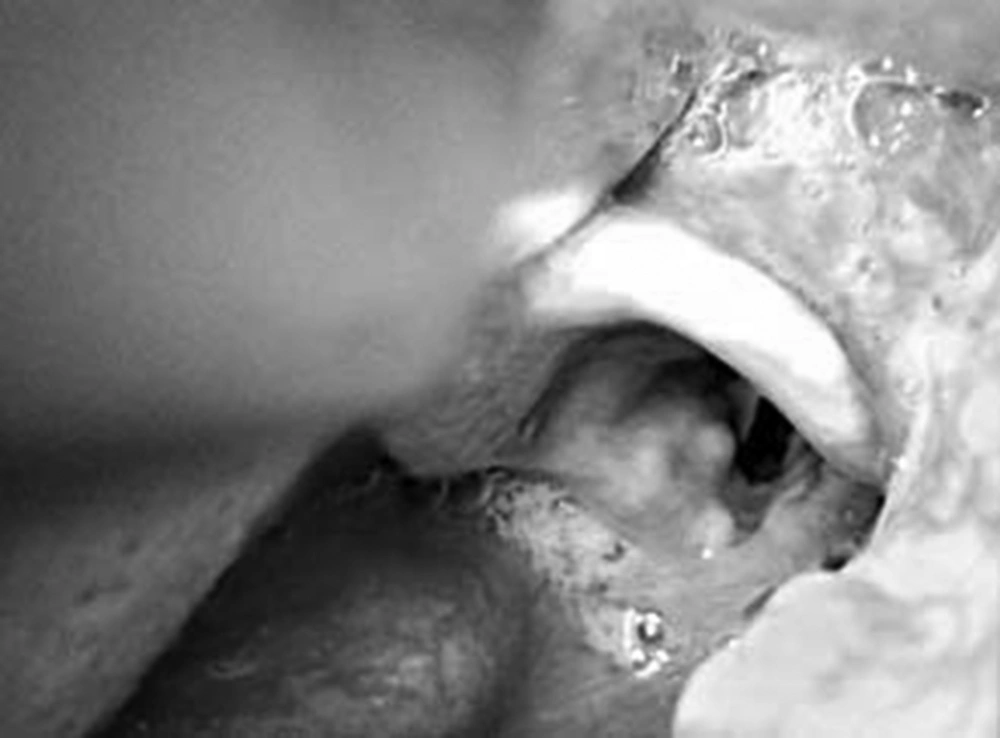

Treatment protocols used in the present report were based on several experiences and became institutional policy and clinical guidelines approved by the IRB of Hosogi Hospital. The treatment guidelines are administered when we have trouble achieving good laryngeal visualization with patients in the ramped position by using a Macintosh 1 to 4 blade and administering external laryngeal manipulation such as the BURP maneuver (the displacement of the larynx in 3mspecific directions: 1. posterior against the cervical vertebrae, 2. as far as superior as possible, and 3. slight displacement to the right) (5): An anesthesiologist turns the patient’s head 35 - 45 degrees to the left while the laryngoscope is fully in place. An assistant helps to rotate and hold the head with the left hand and performs external laryngeal manipulation (ELM) with the right hand to dislocate the Adam’s apple toward the right (Figure 1). The method is so simple and easily performed without any special equipment. In this preliminary study, we recorded the effectiveness of this method on 62 patients who showed poor laryngeal visualization in the ramped position from June 2016 to May 2017. After induction of 7% sevoflurane under assisted ventilation with a bag-mask device and without any muscle relaxants, anesthesiologists, using a Macintosh 1 to 4 blade, assessed the laryngoscopic grade according to the Cormack and Lehane scale before and after our original maneuver with patients in the ramped position (Figures 2 and 3) (2, 3). The characteristics of the 62 patients were as follows: median aged 71 (range; 1 - 100), male = 27, female = 35, median body mass index = 23.0 (range; 12.7 - 34.6). The difference between the obtained views before and after the method was significant (Cormack and Lehane scale; before, 3.0 vs after, 2.03; paired t-test, P < 0.001). However, in 1 female patient the method was not successful. Due to the fact that the opening of the mouth was narrow, there was no room in the mouth to handle the Macintosh blade. Then, intubation was successfully performed by using a McGRATH™ MAC. No subjects complained of laryngeal disturbances postoperatively.

3. Discussion

Airway management is one the most important tasks of anesthesiologists (6, 7). When using direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation, the forward flexion of the cervical spine and backward extension of the head at the atlanto-occipital joint is known to align the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes, thereby increasing visualization of the larynx to some extent (1, 2). Positioning is very important, for example sniff position is recommended for laryngeal mask airway insertion (6). Although one of the most common patient positions applied during difficult intubation is the ramped position (1-3), in our experience, the ramped position fails to provide good laryngeal visualization in some cases. In fact, several reports showed that 5% - 20% of the patients did not improve based on the obtained laryngoscopic grades or even placed in the ramped position (2, 3). One study showed that an AirtraqTM laryngoscope provided an improved vocal cord view, compared with a Macintosh laryngoscope, when used in obese patients in the ramped position (3). No other study showed the effect of other maneuvers in addition to the ramped position on laryngeal visualization.

One old study reported that when placing the patient in the right lateral position, making the head turn about 40 degrees to the left facilitated tracheal intubation (4). We have reported that it is easier to perform induction and intubation with patients in the lateral position (8-10) and in fact we have administered a head rotation to some degrees in addition to the lateral position. Therefore, we speculated that when the ramped position fails to provide good laryngeal visualization, the addition of a head rotation could improve laryngeal visualization and, in fact this case report confirmed our hypothesis.

In conclusion, when the ramped position failed to provide good laryngeal visualization, the addition of a head rotation significantly improved laryngeal visualization.