1. Background

Nowadays, partial hepatectomy is considered to be a selective therapeutic approach in many benign and malignant liver tumors, secondary metastases, and liver trauma (1).

Despite advances in preoperative selection, surgical technique, and perioperative management, post hepatectomy liver failure is still a leading cause of morbidity and mortality following liver resection (2).

According to surgical techniques most often based on vascular control and hepatic venous closure (Pringle maneuver), related complications like ischemia and decreased venous return during and after surgery can be seen, resulting in ischemia-reperfusion injury, the generation of free radicals, and subsequent liver dysfunction.

In many studies, mannitol and N-acetylcystein were studied as effective drugs to reduce the complications of hepatectomy.

2. Methods

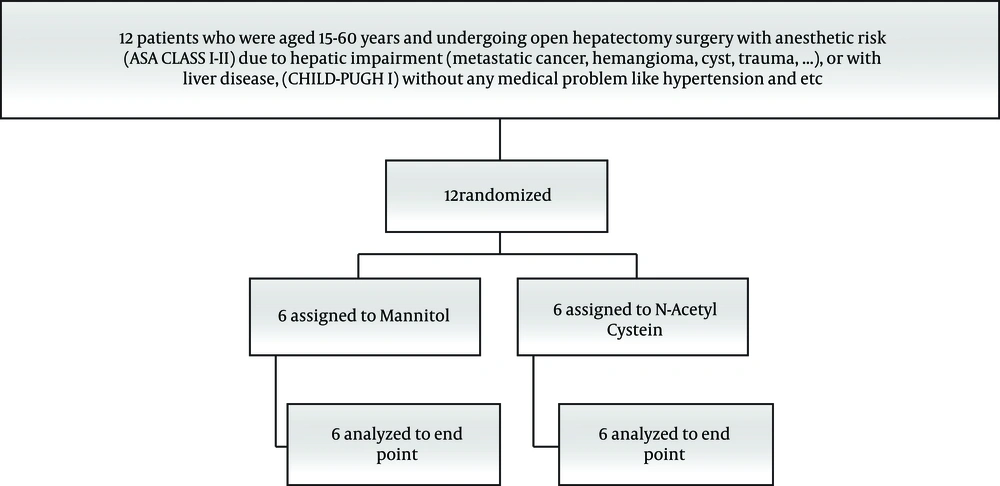

After receiving the authorization from the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, 12 patients (ASA CLASS I-II), with benign or malignant liver lesions, who indicated a hepatectomy, were selected. No blinding was performed.

Based on the location of the tumor site and size, the patient underwent a right lobectomy, left lobectomy, or segmentectomy.

The inclusion criteria for the study were patients aged 15-60 years and hepatic impairment (metastatic cancer, hemangioma, and cyst). The exclusion criteria from the study were; unresectable tumors, coagulation disorder, electrolyte imbalance, renal disease, heart disease, pregnant and lactating females, and patients dying before data collection was completed.

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups: N-acetylcysteine recipients (group N) and Mannitol recipients (group M). All patients were monitored before starting anesthesia with standard monitoring (ECG monitoring, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure monitoring). All patients received 5cc/kg ringer solution using peripheral IV line. The First sample of blood gas was taken after induction of anesthesia. General anesthesia was induced with 0.05 mg/kg of midazolam, 2 mcg/kg of fentanyl, 2 mg/kg propofol, and 0.5 mg/kg of atracurium. Anesthetic maintenance included 1% isoflurane in oxygen-air mixture. In addition to standard monitoring, a radial arterial line and central venous pressure (CVP) catheter in the internal jugular vein were placed. Capnography was used for all patients. In all cases, the surgeon and the surgical procedure were completely the same and united.

As at the start of surgery, group M received 0.25 gr/kg, 20% Mannitol infusion and, group N was given 150 mg/kg of N-Acetylcysteine diluted in 200 mL of 5% glucose, over 60 minutes.

Surgical technique for hepatectomy is the crash clamping technique and the alternate use of the Pringle maneuver. The maximum duration of the maneuver has been 30 minutes.

Then, just before the vascular unclamping, second blood gas and electrolyte sample were taken. The CVP was kept less than 5mmHg, also the arterial blood pressure controlled by infusion of IV Nitroglycerin or vasopressor drug as needed. The last sample in the operating room was taken just before recovery time. Arterial blood gas and electrolytes were assessed before and after vascular clamping, at the end of surgery and 6 hours later in the ICU. BUN and serum creatinine as well as PT, PTT, and INR were measured at the same time. Liver enzymes, AST, ALT, ALKP, and GTT were assessed 24 and 72 hours after surgery.

2.1. Ethical Issues

All patients were given consent to participate in the study if they were satisfied and informed. The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Register code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1396.922).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The results were presented as mean ± SD. To assess the normalcy of the data, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied. To compare the pre and post intervention findings, the Paired t-test was used. To compare the changes between groups, the Student’s t-test was used. P values less than 0.05 were considered. Data were analyzed by SPSS version 22.

3. Results

This study was performed on 12 patients undergoing a partial hepatectomy (Figure 1). Six patients, including four females and two males with an average age of 59 years in group N, received N-Acetyl Cysteine and six patients including four males and two females with an average age of 53.3 years in group M, received Mannitol. There was no significant difference and there was no need to correct the effect of age and sex (P > 0.05).

Along with the electrolytes level and coagulation tests, BUN and serum creatinine were measured at first, before vascular clamping (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, for the second time, they were assessed 20 minutes after clamping, another time was checked before the recovery time, and the last time was checked 6 hours after surgery. There was no significant difference and there was no need to correct the effect of BUN and serum creatinine (P > 0.05).

| Mann-Whitney U | Wilcoxon W | Z | Asymp. Sig. (2-Tailed) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLEED | 17.500 | 38.500 | -0.080 | 0.936 | 0.937 |

| P.C | 10.500 | 31.500 | -1.272 | 0.203 | 0.240 |

| TIME | 14.500 | 35.500 | -0.571 | 0.568 | 0.589 |

| AGE | 11.500 | 32.500 | -1.044 | 0.296 | 0.310 |

| FFP | 15.000 | 36.000 | -0.638 | 0.523 | 0.699 |

| PT1 | 11.000 | 32.500 | -1.251 | 0.211 | 0.310 |

| PT2 | 15.000 | 36.000 | -0.540 | 0.589 | 0.699 |

| PT3 | 12.500 | 33.500 | -0.959 | 0.337 | 0.394 |

| PT4 | 18.000 | 39.000 | -0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| PTT1 | 14.000 | 35.000 | -0.664 | 0.507 | 0.589 |

| PTT2 | 11.500 | 32.500 | -1.054 | 0.292 | 0.310 |

| PTT3 | 11.000 | 32.000 | -1.129 | 0.259 | 0.310 |

| PTT4 | 14.500 | 35.500 | -0.573 | 0.567 | 0.589 |

| INR1 | 9.000 | 30.000 | -1.554 | 0.120 | 0.180 |

| INR2 | 7.500 | 28.500 | -1.750 | 0.080 | 0.093 |

| INR3 | 14.000 | 35.000 | -0.670 | 0.503 | 0.589 |

| INR4 | 17.000 | 38.000 | -0.169 | 0.866 | 0.937 |

| pH1 | 11.000 | 32.000 | -1.127 | 0.260 | 0.310 |

| pH2 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.324 | 0.746 | 0.818 |

| pH3 | 8.000 | 29.000 | -1.607 | 0.108 | 0.132 |

| pH4 | 5.000 | 26.000 | -2.342 | 0.019 | 0.041 |

| BE1 | 13.500 | 34.500 | -0.754 | 0.451 | 0.485 |

| BE2 | 12.000 | 33.500 | -0.969 | 0.332 | 0.394 |

| BE3 | 6.500 | 27.500 | -1.871 | 0.061 | 0.065 |

| BE4 | 12.000 | 33.000 | -0.998 | 0.318 | 0.394 |

| pco21 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.325 | 0.745 | 0.818 |

| pco22 | 14.500 | 35.500 | -0.562 | 0.574 | 0.589 |

| pco23 | 18.000 | 39.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| pco24 | 16.500 | 37.500 | -0.247 | 0.805 | 0.818 |

| Hco31 | 17.000 | 38.000 | -0.162 | 0.871 | 0.937 |

| Hco32 | 9.000 | 30.000 | -1.451 | 0.147 | 0.180 |

| Hco33 | 7.500 | 28.500 | -1.747 | 0.081 | 0.093 |

| Hco34 | 10.000 | 31.000 | -1.304 | 0.192 | 0.240 |

| AST1 | 17.000 | 38.000 | -0.161 | 0.872 | 0.937 |

| AST2 | 16.500 | 37.500 | -0.241 | 0.810 | 0.818 |

| ALT1 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.321 | 0.748 | 0.818 |

| ALT2 | 18.000 | 39.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| ALP1 | 15.000 | 36.000 | -0.480 | 0.631 | 0.699 |

| ALP2 | 12.500 | 33.500 | -0.884 | 0.377 | 0.394 |

| GGT1 | 14.500 | 35.500 | -0.561 | 0.575 | 0.589 |

| GGT2 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.321 | 0.748 | 0.818 |

a Grouping variable: group.

b Not corrected for ties.

| Mann-Whitney U | Wilcoxon W | Z | Asymp. Sig. (2-Tailed) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bun1 | 8.000 | 29.000 | -1.615 | 0.106 | 0.132 |

| Bun2 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.322 | 0.747 | 0.818 |

| Bun3 | 14.500 | 35.500 | -0.563 | 0.573 | 0.589 |

| Bun4 | 11.000 | 32.000 | -1.152 | 0.250 | 0.310 |

| Cr1 | 15.000 | 36.000 | -0.506 | 0.613 | 0.699 |

| Cr2 | 18.000 | 39.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Cr3 | 9.000 | 30.000 | -1.475 | 0.140 | 0.180 |

| Cr4 | 15.000 | 36.000 | -0.538 | 0.591 | 0.699 |

| Na1 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.322 | 0.747 | 0.818 |

| Na2 | 16.000 | 37.000 | -0.325 | 0.745 | 0.818 |

| Na3 | 7.000 | 28.000 | -1.790 | 0.073 | 0.093 |

| Na4 | 17.000 | 38.000 | -0.168 | 0.867 | 0.937 |

| k1 | 18.000 | 39.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| k2 | 12.000 | 33.000 | -0.982 | 0.326 | 0.394 |

| k3 | 9.500 | 30.500 | -1.371 | 0.170 | 0.180 |

| k4 | 14.500 | 35.500 | -0.576 | 0.565 | 0.589 |

| ca1 | 13.000 | 34.000 | -0.811 | 0.418 | 0.485 |

| ca2 | 11.000 | 32.000 | -1.133 | 257 | 0.310 |

| ca3 | 15.500 | 36.500 | -0.405 | 0.685 | 0.699 |

| ca4 | 12.500 | 33.500 | -0.910 | 0.363 | 0.394 |

a Grouping variable: group.

b Not corrected for ties.

The hepatic enzymes ALT, AST, GGT, and Alkaline phosphatase, were checked 24 hours and three days after surgery. There was no significant difference and there was no need to correct the effect of medications.

There was no significant difference between two groups in coagulation status, amount of bleeding, need to transfusion of the packed cell, and FFP (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

There was no significant difference between two groups in blood gas status, except in terms of PH, (P = 0.041) (Table 1). It seems that there is a slight difference in Base deficit and more need for correction in group M was detected; however, it is not statistically meaningful (P > 0.39) (Table 1).

There was no significant difference between two groups in electrolytes and kidney function and no need to correct the effect of electrolytes (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

A comparison of laboratory values between two groups in liver enzymes was the main process of the study. There is a faster reduction of liver enzymes in the N-acetylcysteine group after 3 day’s postoperative, however, statistically it is not meaningful (P = 0.81; P = 1; P = 0.39; P = 0.81) (Table 1).

Our study showed that the Mannitol group in comparison with the N-acetylcysteine group had no significant difference in liver function, hemodynamic status, and electrolyte and coagulation disorders after surgery.

4. Discussion

In spite of our study, Kortsalioudaki et al. (3), in 2008, found a positive effect of N-acetylcysteine as an antioxidant in acute liver failure, as well as a reduction in hospitalization and decreasing the need for liver transplantation and increasing survival after transplantation.

Byrka-Owczarek et al. (4), showed the protective effect of mannitol and N-acetylcysteine in ischemic reperfusion injury. On the basis of histopathologic results, the strongest protective action was shown by Mannitol and the smallest one by N-acetylcysteine.

Shawkat et al. (5), in 2012, also found reducing the risk of acute renal failure next to liver transplant surgery by infusion of 25 grams of Mannitol before operation. Mannitol reduces post-ischaemic endothelial cell swelling and decreases ischaemic–reperfusion injuries through scavenging of hydroxyl and other free radicals.

Snowden and Prentis showed that the use of N-acetylcysteine does not reduce alanine aminotransferase levels, suggesting that it does not reduce hepatocellular injury (1).

In the study by Kemp and et al. (6), in 2017, no significant improvement in post-operative outcomes with the administration of N-acetylcysteine was reported.

Grendar et al. (7), assessed the effect of N-acetylcysteine on liver recovery after resection; patients randomized to postoperative N-acetylcysteine received no benefit.

In study by Fathi et al. (8), in 2016, N-acetylcysteine effect on liver function was assessed in coronary bypass graft surgery patients. It showed a reduction in liver enzymes comparable with the control group. Therefore, the study advised that all patients undergoing CABG receive 150mg/kg prophylactic N-acetylcysteine before surgery.

In spite of these, in our study, similar results were not obtained from N-acetylcysteine and Mannitol, and no statistically significant correlation was found between the two drugs.

4.1. Limitations

The sample size is low, and the measurement of oxidative stress markers also contributed to the validity of the study that could not be assessed in this study.

4.2. Conclusion

In spite of the limitations in this study it was showed that infusion of Mannitol beside N-acetylcystein in partial hepatectomy surgeries had no significant difference to improve liver function, hemodynamic status, and laboratory tests.