1. Background

Low-back pain (LBP) is one of the most common causes of chronic pain patients’ referring to hospitals. It is shown that 70% - 85% of people may suffer from LBP throughout their lives (1). The pain can radiate to the lower limbs. It is most commonly caused by the secondary mechanical pressure to the herniated disc or foraminal stenosis, leading to inflammatory processes and pain (2). Changes in plasma levels of calcium and magnesium occur in patients with chronic lumbar pain (3, 4), which are positively correlated with the plasma vitamin D level that is apparently low in such patients (5). The primary treatment of the lumbar radicular pain involves medication, physiotherapy, and epidural steroid injection (ESI) (6). Narcotics can also be used to manage the patients’ pain, but they are associated with some adverse side effects (7). One of the methods for controlling lumbar radicular pain is transforaminal steroid injection, which has been gaining popularity over the past years due to its particular features such as more specificity, less injection volume, and penetration to the main pathologic site (8). However, ESI is associated with some complications including a headache, flushing, water retention, metabolic and endocrine changes, increased blood sugar, osteoporosis, and occasionally rare complications such as spinal cord infarction and even death (9). Electrolyte disturbances and vitamin D deficiency can be associated with lower back pain, as the relationship between low intake of dairy products and inadequate calcium and that between a decreased serum level of vitamin D and the occurrence of lumbar pain have been demonstrated (10).

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha-2 agonist that has sedative and analgesic effects without affecting respiratory depression; its analgesic effect is achieved by affecting areas on the spinal cord and above the spinal cord (11, 12). In some studies, its addition as an adjunct to local anesthetics in epidural and intrathecal anesthesia has produced better analgesia after surgery (13, 14).

2. Objectives

Although numerous studies have been reported on transforaminal steroids, a few studies have been made to investigate the impacts of transforaminal dexmedetomidine on lumbar radicular pain. Thus, to prevent the occurrence of steroid complications in the transforaminal block, we investigated the effects and side effects of transforaminal triamcinolone and dexmedetomidine in patients with lumbar radicular pain.

3. Methods

Following approval of the university’s Ethics Committee and receipt of the clinical trial registration code (IRCT201312037984N12), written informed consent was obtained from the study subjects before their enrollment in the study. In this randomized double-blind clinical trial, we evaluated 30 patients (both sexes) aged 40 - 70 years, with ASA I-II, having severe lumbar radicular pain (for more than six weeks), not responding to conservative treatment (for at least four weeks). Further inclusion criteria were lumbar disc protrusion at one or two segmental levels on MRI, visual analoguescale (VAS; 0 - 10) of greater than 4, and positive straight leg raise (SLR) or Lasègue’s test at 30 - 70 degrees. The exclusion criteria included lumbar disc extrusion or sequestration, neurological deficits, vertebral deformities such as scoliosis and spondylolisthesis, history of spinal surgery, coagulation abnormalities, local infection, severe psychiatric disorders, allergy to study drugs, cancer, pregnancy, drug abuse, obesity (BMI > 30), and patient refusal.

Based on the formula n = {2(z1-α/2 + z1-b)2 δ2/d2}, the sample size was calculated as 30 patients.

By using the four-block method of randomization, patients were randomly divided into two equal groups of 15 subjects. To make the study double-blind, neither the patients nor the researchers were aware of the type of intervention performed.

After the Scottie dog sign was determined using fluoroscopy on the 20° oblique view, a lumbar transforaminal block was performed under sterile conditions and local anesthesia with inserting a 16-gauge introducer needle underneath the intersection of the transverse process and the pedicle. After removing the stylet, a blunt, curved-tip needle (Gauge 21 and 100 mm in length) was inserted in the tunnel vision. After making sure that the needle’s tip was properly placed on the antero-posterior and lateral views, 2 mL of water-soluble, non-ionic contrast agent (Visipaque 270) was injected. Then, the injectate was slowly administered. The injection solution contained 20 mg triamcinolone (Triamcinolone acetonide, Exir, Iran) and 4 mL ropivacaine 0.2% (Ropivacaine, Molteni, Italy) in the triamcinolone (T) group and 50 µg dexmedetomidine (Precedex, Pfizer, USA) and 4 mL ropivacaine 0.2% in the dexmedetomidine (D) group. In the case of two-level involvement, the same dose was administered for the next level. After ensuring that the patients’ conditions (e.g. hemodynamics, consciousness) were stable, they were discharged with oral pregabalin (Lyrica, Pfizer, Germany) 75 mg before bedtime, and in the case of VAS > 3, acetaminophen 500 mg was administered every six hours. The evaluation criteria included VAS (0 - 10), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), SLR or Lasègue’s test, and Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS) that were assessed at baseline, two weeks, one, three, and six months after the procedure. The plasma calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D at the baseline and the next six months, as well as the potential complications, were evaluated. Also, demographic data (age and gender) were recorded.

In follow-up visits, if the improvement was above 80%, we would only perform the follow-up and continuation of treatment. If the improvement was between 50% and 80%, a re-injection (at most two times) would be performed, and if the improvement was below 50% or neurological complications were observed, a neurosurgical consultation would be performed.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive results are presented as mean ± SD or percentages. T-test was used to compare means. ANOVA repeated measure was used to compare the mean of quantitative variables over time. P value < 0.05 was considered significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 21 software.

4. Results

The results of demographic data, pain score (VAS), and ODI are shown in Table 1. Since the Mauchly’s sphericity test was significant (P < 0.001), the VAS and ODI values measured over time between the two groups were reported as single-variable results. Moreover, there was a meaningful difference between the two groups in the intra-group effects at all five time-points (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

| T | D | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 62.7 ± 13.3 | 52.4 ± 9.9 |

| Gender (m:f) | 5:10 | 3:12 |

| VAS | ||

| Baseline | 7.7 ± 1.1 | 8.8 ± 1.0 |

| 2nd w | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 2.2 |

| 1st m | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 1.5 |

| 3rd m | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 2.5 ± 1.7 |

| 6th m | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 2.4 ± 1.6 |

| ODI | ||

| Baseline | 49.7 ± 16.3 | 67.3 ± 5.9 |

| 2nd w | 35.3 ± 15.1 | 28.8 ± 16.9 |

| 1st m | 30.6 ± 14.2 | 17.3 ± 10.4 |

| 3rd m | 35.4 ± 12.7 | 15.7 ± 11.0 |

| 6th m | 37.6 ± 12.0 | 15.3 ± 11.1 |

Demographic Data, VAS, and ODI in T and D Groupsa

VAS was significantly different between the two groups at all time-points (Table 2); in addition, the ODI was remarkably different at the first, third, and sixth months after the procedure, but no meaningful difference was found at the second week (i.e. the first post-procedure evaluation time between the two groups) (Table 2).

| t | Mean Difference | Standard Error | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | ||||

| Baseline | -2.874 | -1.133 | 0.394 | 0.008 |

| 2nd w | -0.091 | -0.067 | 0.731 | 0.928 |

| 1st m | 2.553 | 1.533 | 0.601 | 0.016 |

| 3rd m | 4.647 | 3.067 | 0.660 | < 0.001 |

| 6th m | 5.315 | 3.467 | 0.652 | < 0.001 |

| ODI | ||||

| Baseline | -3.933 | -17.600 | 4.474 | 0.001 |

| 2nd w | 1.115 | 6.533 | 5.860 | 0.274 |

| 1st m | 2.925 | 13.333 | 4.558 | 0.007 |

| 3rd m | 4.543 | 19.733 | 4.344 | < 0.001 |

| 6th m | 5.274 | 22.267 | 4.222 | < 0.001 |

Comparison of Mean VAS and ODI in T and D Groups

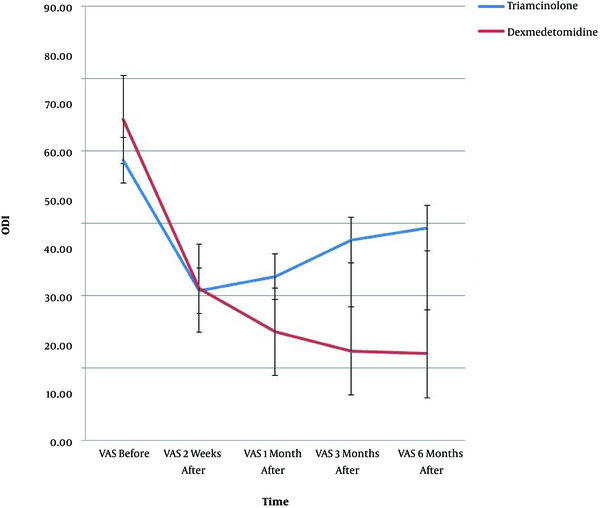

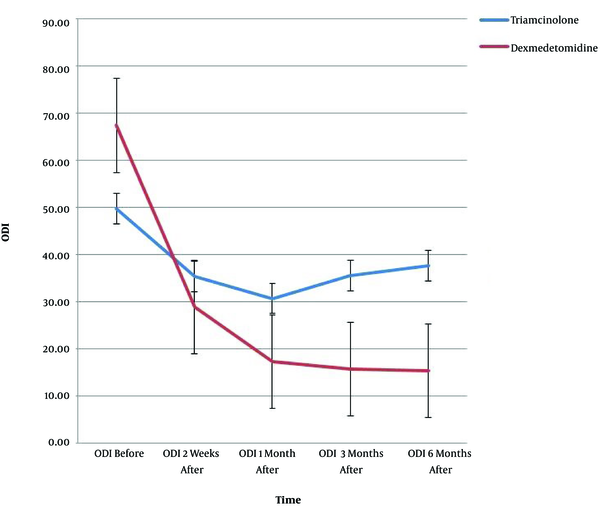

VAS and ODI showed significant interactions of time and group (P < 0.001); there was a remarkable difference in VAS (P < 0.001) and ODI (P < 0.02) between the two groups at the measurement time-points. Figures 1 and 2 show the trend of changes in VAS, ODI, and the error bar thereof for the two groups at various time-points.

No meaningful difference was found in FBS between the two groups at baseline, but there was a significant difference in two weeks and one month after the procedure (Table 3).

| t | Mean Difference | Standard Error | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1.681 | 10.067 | 5.988 | 0.104 |

| 2nd w | 2.476 | 15.933 | 6.435 | 0.020 |

| 1st m | 2.236 | 12.733 | 5.696 | 0.034 |

Independent t-Test for FBS in T and D Groups (Baseline and the Next Two Weeks and One Month)

There was a significant difference in calcium and vitamin D levels between the two groups, but no considerable difference was shown in the magnesium level in the two groups (Table 4).

| Mean | Std. Deviation | t | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 | Ca before - 1st m | -.683 | 0.702 | -5.326 | < 0.001 |

| Pair 2 | Mg before - 1st m | -7.020 | 38.455 | -1.000 | 0.326 |

| Pair 3 | Vit. D before - 1st m | -19.553 | 27.596 | -3.881 | 0.001 |

Paired t-Test for Calcium, Magnesium, and Vitamin D in T and D Groups (Baseline, and the Next One Month)

The SLR or Lasègue’s test showed a significant difference between the two groups at all assessment time-points (P < 0.001). No complications were observed in patients during the study and there was no need to repeat the block.

5. Discussion

This study showed that, compared to triamcinolone, dexmedetomidine significantly reduced the VAS and ODI for up to six months. In the triamcinolone group, increased FBS and decreased calcium and vitamin D were significantly different from the decreases in the dexmedetomidine group, but changes in magnesium levels were not remarkably different between the two groups. Corticosteroids injection is currently associated with rare, but serious, side effects including loss of vision, stroke, and paralysis (15). Although the US Federal Drug Association (FDA) has announced a warning for the administration of epidural corticosteroids, several studies have shown that no serious concerns are anticipated about the occurrence of severe neurological complications if the principal points are observed at the time of administration (16, 17). Thus, to prevent the incidence of such threatening, though rare, complications, other safer alternatives are proposed to evaluate for transforaminal blocks (18).

Many papers have been published on the safety, outcomes, and benefits of administration of various types of corticosteroids and other adjuvant agents in the transforaminal block for chronic lumbar pain. Today, it is generally proposed to administer non-particulate corticosteroids (e.g. betamethasone) rather than particulate ones (e.g. triamcinolone), and it has not been proven that the latter has better and prolonged analgesic effects (19). However, enhancing the dose of betamethasone from 3 to 6 mg for transforaminal block produced no effect on the reduction of VAS and the amount of oral analgesic taken for up to four weeks (20); even in a study, the addition of corticosteroid to epidural lidocaine did not have further effects on the treatment of spinal stenosis (21). Conversely, in some studies, transforaminal triamcinolone has shown to produce better and prolonged analgesia than betamethasone (22); in another study, Kim et al. reported that the administration of triamcinolone was associated with higher efficacy and satisfaction than the administration of epidural dexamethasone (23).

In a meta-analysis, the efficacy and safety of a transforaminal steroid were not well understood as compared to an anesthetic or saline solution for lumbar radicular pain caused by the lumbar disc protrusion (24). The analysis also showed that not only did transforaminal steroid have short-term analgesic effects lasting only for three months, but it also had little effect on the physical disability and the incidence of subsequent surgical procedures, which, of course, was due to the heterogeneity of studies in design. Hence, more random, precise, and extensive studies were proposed to do to determine the appropriate dose of transforaminal steroid, as well as to evaluate the prevalence of its complications, frequency of block repetition, mental effects, and quality of life. Therefore, considering the possible side effects of transforaminal steroid injection, another method should also be sought to not only reduce the likelihood of potentially dangerous, though rare, side effects, but can also provide proper analgesia and improve the quality of lives of patients (25, 26).

Dexmedetomidine, a highly selective alpha-2 agonist, increases the activity of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus in the brainstem and consequently, enhances the inhibitory activity of gamma-amino-butyric acid in the ventrolateral preoptic neurons, eventually improving the sedative effects. In addition, it affects some areas on the spinal cord and above the spinal cord that causes analgesic effects (11).

Adding dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to paravertebral and supraclavicular blocks has caused better analgesia and lower postoperative analgesic consumption (27, 28). In a study, Bajwa et al. administered dexmedetomidine, as an adjunct in epidural anesthesia, and reported its better effects compared to clonidine; it also improved patients’ comfort, cardiovascular parameters, and analgesia during the surgery and post-surgery (29). Furthermore, in postoperative pain management, the addition of dexmedetomidine induced more considerable analgesia and decreased the amount of the analgesics administered in the early postoperative period (30, 31). In a meta-analysis conducted in 2017, the addition of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant in epidural anesthesia showed to be usually safe and well-tolerated. In addition, acting synergically, it intensified analgesic and sedative effects (32).

Considering the significant effects of adding dexmedetomidine to the anesthetic agents in epidural anesthesia as reported so far, the authors of this paper compared dexmedetomidine and triamcinolone in the transforaminal block in patients with lumbar radicular pain since, on the one hand, there always exists a potential concern for serious complications attributed to transforaminal steroids, and on the other hand, some common, though less dangerous, side effects always threaten patients’ lives, the most prominent and fastest of which is hyperglycemia. Besides, another concern about the administration of steroids, especially in elderly patients, is the onset of osteoporosis. Several direct and indirect mechanisms are described for bone resorption after corticosteroid administration (33). At high-risk patients, vitamin D and calcium supplements should immediately start. Therefore, the prevention of calcium and vitamin D reduction may be useful for high-risk subjects. For these reasons, in our study, serum calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D levels were evaluated. Interestingly, the administration of transforaminal steroid reduced calcium and vitamin D levels in patients of the triamcinolone group, which was significantly different from the reductions in the dexmedetomidine group. To reduce the likelihood of hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes, osteoporosis, and low calcium or low vitamin D levels, dexmedetomidine can be considered as an appropriate alternative to triamcinolone. In addition, a greater reduction in the VAS and ODI following transforaminal dexmedetomidine, compared to following triamcinolone, observed in this study, can make dexmedetomidine as the primary choice for these patients.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study showed that the transforaminal block with triamcinolone and dexmedetomidine had a significant effect on the reduction of pain score (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) in patients with lumbar radicular pain and that dexmedetomidine had more beneficial effects than triamcinolone.