1. Background

Pain is one of the main complaints of many patients in intensive care units (1). The reports of moderate to severe pain experiences in these patients are worrying (2). If patients' pain is not managed properly and effectively, it can lead to physical injuries, psychological consequences (3), and complications such as delayed recovery, increased length of stay, increased health care costs, and decreased patient satisfaction (4-6).

Despite the importance of this issue and efforts made in the last 30 years in the field of pain management and existing standards (7) and valid guidelines (8-11) such as Pain, Agitation, Delirium (PAD), Japanese guidelines for the management of PAD (J-PAD), Federacion Panamericana e Iberica de Sociedades de Medicina Critica y Terapia Intensiva (FEPIMCTI) (12), various training courses, applied strategies, and multidisciplinary pain teams, there are still deficiencies in the field of pain management (13) and patients’ pain control remains a major challenge in patients hospitalized in intensive care units (14). Most nurses and physicians are unable to properly monitor and relieve the pain of critical patients (7) because proper pain management is a difficult task for many reasons such as patients’ inability to describe their pain (3), using sedatives, mechanical ventilation, and unstable physiological status (15, 16). On the other hand, the insufficient knowledge of nurses and physicians (14, 17) and lack of proper assessment and administration of analgesic interventions are other challenges in the field of pain management (17).

Despite the important role and position of intensive care nurses in the assessment and management of patients’ pain, many texts refer to poor knowledge (18-22) and attitude of nurses toward pain and pain management in patients (18-20). Poor attitude of nurses leads to a lack of pain perception in unconscious patients and the lack of the implementation of a nonverbal pain scale. Poor knowledge of nurses also results in unfamiliarity with the implementation of nonverbal pain scales, inability to clinically use pain scale (23) and inadequate pain control (24). Pain management is, thus, considered a prerequisite knowledge for nurses (19).

According to the reported results, only a small number of nurses provide appropriate care when the patient is experiencing pain. However, they have a moral responsibility to provide the best clinical care in pain relief (25). The nurses' awareness and attitude play an important role in the implementation of an effective pain management process (26) and the results of previous studies showed that training programs in the field of pain significantly enhance the nurses' knowledge and attitude toward pain (27, 28). Training in intensive care units should encourage critical care nurses (CCNs) to understand and confidently use pain assessment tools (16). Continuous training on pain management, regular feedback sessions (29), and implementation of pain management programs can also have a positive impact on increasing the nurses’ knowledge and attitude (26-30). Additionally, pain control guidelines can increase the effectiveness of nurses' clinical practice (31), but it should be noted that a comprehensive pain management program should consider not only prevention, but also all the three phases of pain management including diagnosis, treatment, and reassessment of pain (7).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the impact of a comprehensive pain management training program and its application on improving the awareness and attitude of intensive care unit nurses. It is hoped that the results of this study can be a useful guide to improve pain management in intensive care units.

3. Methods

This quasi-experimental study was part of a larger study entitled “Investigating the Impact of Pain Management Program on the Quality-of-Care Indicators in Adult Intensive Care Unit”, which was conducted from May 2018 to May 2019 on all nurses meeting the inclusion criteria and working in the general intensive care unit of Shahid Modarres University Hospital. The inclusion criteria consisted of employment in the general ICU, having at least an associate’s degree, and six months of intensive care unit experience. The exclusion criteria consisted of ceasing cooperation at any stage of the study due to various reasons (long leave, lay-off, or retirement) or cooperation at only one stage of the study (pre- or post-intervention).

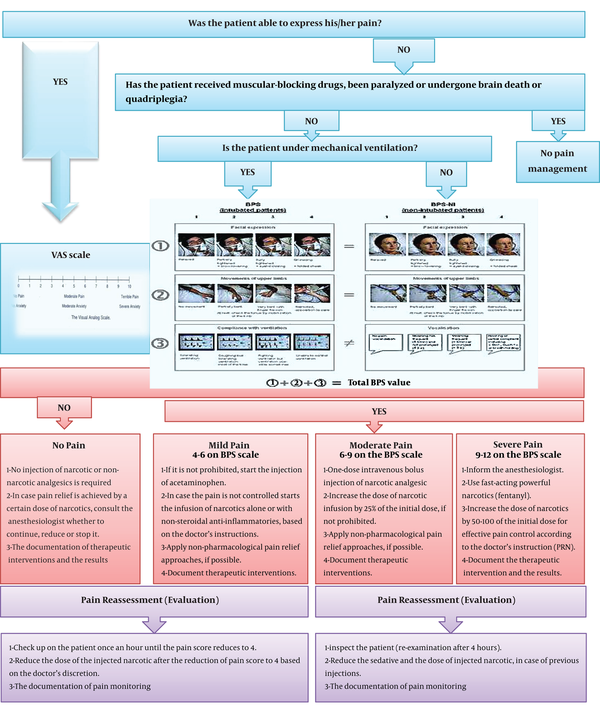

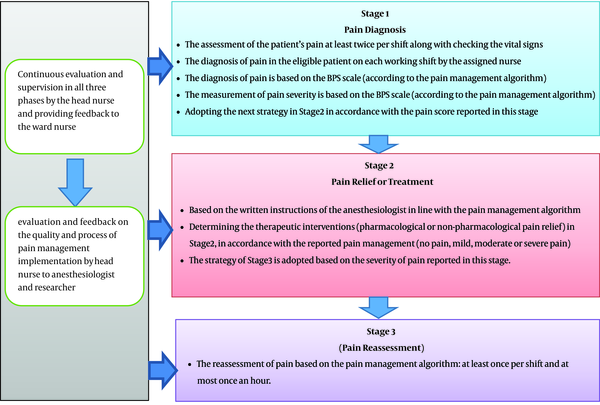

To design the educational content, we carried out an extensive, systematic review of pain management algorithms and programs in intensive care units. One study was selected that, compared to other studies, had appropriate indicators: having brief steps, easy clinical application, proper valid pain diagnosis scales, and assessment pain scale in patients with or without intubation (32). Then, due to the lack of transparency in the implementation process of therapeutic interventions in the existing algorithm, WHO and Shahriari et al.’s (33) pain control models were used to make the algorithm more understandable. Then, to examine the face and content validity of the designed program, the opinions of 10 specialists and experts in the field of pain and intensive care and four experienced nurses were collected (CVR: 0.85). In the end, the final pain management program in the three stages of pain diagnosis, relief, and reassessment was formulated with an emphasis on non-pharmacological pain relief and pain management documentation (Figures 1 and 2).

In the next step, before the implementation of the pain management training program, the nurses' level of awareness and attitude toward pain management was assessed by a three-part questionnaire in the pre-intervention phase. The questionnaire was developed using expert opinions through a comprehensive text review. The first part of this three-part questionnaire included demographic information (sex, age, education, working experience in ICUs, history of participation in training courses in the field of pain or pain management). The second part contained 18 items for assessing the nurses' attitude toward pain management by a five-point Likert scale. The third part consisted of 19 binary choice items (true-false). The validity of the questionnaire was examined by 10 faculty members and clinical experts in the field of intensive care and pain, and its reliability was approved by a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.78 and ICC of 0.95.

In the intervention phase, two-day workshop training was held on comprehensive pain management. At the beginning of the workshop, lectures on the physiology and importance of pain management were presented. The researcher, then, introduced the main stages of comprehensive pain management, the method of using the pain management algorithm, and the implementation process of the management program. At the end of the workshop, a hypothetical scenario of a patient's condition was presented to small groups, and nurses were trained in implementing the pain management algorithm concerning the presented scenario. In the end, each of the groups reported how they managed pain and challenges, and the researcher discussed and summarized the results and made the final conclusion. In addition to oral training, educational packages were provided to all participating nurses. This package included a pain management booklet, a small poster of the pain management algorithm, and the behavioral pain scale (BPS). Moreover, before the intervention phase, a description of the tasks of the members involved in the implementation was given (supplementary file Appendix 1). In addition to installing the documentation of job description and a poster explaining the pain management algorithm and the process of program execution, oral notices were also made by the head of the ward for all nurses and participants involved in the research. Accordingly, the nurses and other members of the treatment team were asked to manage pain in eligible patients. Eligible patients were aged between 18 and 70 years, their levels of consciousness were 7 to 11 based on the Glasgow criteria (11-7), received no muscle relaxants (no paralysis), and had not self-reported pain and malignancy. Moreover, they would not have the experience of being hospitalized in surgical services.

In the post-intervention phase, which began two weeks after the intervention, the nurses' awareness and attitude were again assessed by the above questionnaire. Finally, the data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 and the changes in the nurses’ awareness and attitude in the two pre- and post-intervention phases were compared using the Wilcoxon test.

3.1. Ethical Considerations

Before the intervention, informed consent was obtained from the nurses participating in the study for both pre- and post-intervention phases. Written consent was obtained in line with the policies of the Research Ethics Committee.

An identification code was assigned to each of the nurses participating in the study. The confidentiality of the participants’ information and their anonymity was guaranteed. In both phases, before and after applying the intervention, the list of the participants’ names and codes were kept confidential and they were separated from the collected data and only the research team was allowed for access.

4. Results

The results of this study showed that the majority of the nurses who participated in both pre- and post-intervention phases were female, with a mean age of 35 years, holding a B.Sc. degree, a job experience of three to 10 years of working in intensive care units, and with no history of participation in training courses before the intervention (Table 1).

| Demographic Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 29 | 90.6 |

| Male | 3 | 9.4 |

| Age | ||

| (20 - 30) | 7 | 21.9 |

| (31 - 40) | 20 | 62.5 |

| (41 - 50) | 5 | 15.6 |

| Education | ||

| Associate’s degree | 1 | 3.1 |

| B.Sc. degree | 25 | 78.1 |

| M.Sc. degree | 6 | 18.8 |

| Job experience of working in ICUs | ||

| 3 years or less | 10 | 31.2 |

| 3 - 10 years | 15 | 47 |

| 10 - 15 years | 3 | 9.4 |

| 15 - 20 years | 2 | 6.2 |

| More than 20 years | 2 | 6.2 |

| History of participation in pain management training courses (before intervention) | ||

| Yes | 9 | 22 |

| No | 32 | 78 |

Demographic Data of Nurses Participating in the Study

In the pre-intervention phase, the attitude and awareness of 41 nurses were assessed. Based on the exclusion criteria, nine nurses were excluded after the intervention. The final results are reported based on the study of 32 nurses who participated in both phases. In the pre-intervention phase, 12.2% of the 41 nurses under study had a moderate awareness score, while 87.8% of them gained a higher than the moderate score. In the post-intervention phase, the majority of the nurses (93.8%) obtained scores higher than moderate (Table 2).

Moreover, in the pre-intervention phase, 85.4% of the nurses had a high attitude score and 14.6% of them had a moderate attitude score concerning pain management in critically ill patients. While in the post-intervention phase, only one nurse had a moderate attitude score concerning the above topic and 96.9% of them had a high attitude score about pain management (Table 3).

| Attitude Score | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 58 - 86 | 35 (85.4) | 31 (96.9) |

| 30 - 58 | 6 (14.6) | 1 (3.1) |

| 0 - 30 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Frequency and Percentage of Scores for Nurses’ Attitude Toward Pain Management in ICU Patients Before and After Interventiona

The results of the test indicate that the implementation of the pain management program enhanced the nurses’ awareness in this field and there was a significant increase in the mean scores of the nurses’ awareness in the post-intervention phase compared to the pre-intervention phase (P < 0.05). However, despite the increase in their attitude scores after the intervention (71.03), no statistically significant change was observed (Table 4).

| Score | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Before-After Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max | Mean | Standard Deviation | Wilcoxon Test P Value | |

| Awareness | 13 | 19 | 16.04 | 1.67 | 12 | 19 | 16.06 | 1.79 | 0.003 |

| Attitude | 65 | 86 | 65.88 | 7.03 | 58 | 83 | 71.03 | 6.59 | 0.209 |

Comparison Between the Scores of Awareness and Attitude of Nurses Concerning Pain Management in ICU Patients Before and After Intervention

The results of Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests showed that the only significant relationship existed between the working experience in ICUs and the nurses’ attitude, while no significant relationship was seen between nurses' awareness and demographic variables (level of education, working experience in the intensive care unit, and history of participation in pain management training courses) (Table 5).

Relationship Between Demographic Variables and Nurses' Awareness and Attitude Scores on Pain Management (Pre-Intervention)

5. Discussion

The promotion of the nurses' knowledge and attitude toward pain management has been investigated in many studies. Despite the implementation of various interventions in this field, deficiencies are still mentioned in pain management. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the impact of a comprehensive pain management training program and its implementation on the improvement of awareness and attitude in ICU nurses. In the pre-intervention phase, most nurses had scores higher than the average score though there was a potential for improvement and growth. In line with the results of the current study, the results of a study conducted by Souza et al., which examined pain management awareness in 113 nurses in three groups of nursing experts, nursing technicians, and professional nurses, reported the awareness of professional nurses as satisfactory, with a potential for more growth and improvement (1). Furthermore, in a study by Asman et al., which assessed the awareness of pain management in 187 ICU nurses, acceptable scores were reported for the nurses' awareness of pain behaviors of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation (34).

Although the current study along with some other studies referred to acceptable awareness among nurses, yet with a need for improvement, most studies mentioned insufficient knowledge and awareness of nurses and the treatment team on pain management. Due to the lack of pain management training in the curriculum of nursing and medical students, they are not properly prepared to address patients' pain needs (35). Moreover, the quality of pain management training does not meet the international standards of nursing care (36) and not much attention has been paid to pain management in nursing education (37).

The results of a cross-sectional study by Yava et al., which was conducted on 264 Turkish nurses, indicated that nurses did not have sufficient awareness and a positive attitude toward pain management (31). Khalil et al. found that only 4 out of 417 Jordanian nurses under study gained acceptable scores on the NKAS (“Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain” the tool used to assess “nurses” level of knowledge and attitudes toward pain and pain management) questionnaire. They had negative attitudes toward and inadequate knowledge of pain management (20). The study by Salameh et al. also reported deficiencies in the Palestinian nurses' knowledge of pain management in intensive care units (19). A study by Aflatoonian et al. at several treatment centers in Jiroft (Iran) also indicated that 70% of nurses had moderate and negative attitudes toward pain assessment and management, which reflected their very low information on pain management. In addition to the mentioned studies, the scores of nurses' awareness and attitude were reported to be poor in countries such as Kenya, India, and Taiwan (18, 26, 38).

The results of this study showed that after training and implementing the pain management program, the nurses' awareness of pain management improved and their mean attitude scores also increased. In different studies, different methods were applied to teach pain management and assess their impacts on the awareness, attitudes, and skills of nurses. In the study by Bjorna et al., the impact of the video education of pain management on nurses’ awareness and attitude was examined in Finland and the results indicated that video education was a useful method for enhancing the awareness and skills of nurses in using the behavioral pain assessment scale in ICUs (39). In a study by Lewis et al. on southeastern US nurses, the implementation of brief group discussions to increase the nurses' awareness of pain management was reported to be effective (30). According to another study by Machira et al., the training and implementation of a pain management program had a positive impact on the knowledge and attitude of Kenyan nurses (26). The results of studies by Smolle et al. at Austrian hospitals, which were conducted to assess the sustainability of a pain management quality assurance program (PMQP), showed that the implementation of PMQP led to a high standard of care, and continuous education, ongoing training, regular courses, and implementing feedback loops would ensure the continuity and the increase of knowledge and competency in nurses and physicians (29). However, a study by Schreiber et al. in Kentucky, USA, to assess the impact of training interventions on the nurses' knowledge of pain management in critically ill patients, showed that the nurses' awareness scores were not significantly different before and after the intervention (24).

The results of the present study and the examination of the relationship between the background variables and the nurses’ awareness and attitude showed a significant relationship between working experience in ICUs and nurses’ attitudes. However, different studies have reported different results on this matter. In the study by Salameh et al., except for the education level, no significant relationship was reported between demographic characteristics and the total score of the nurses' awareness and attitude (19). However, according to some studies, significant positive correlations existed between the level of education (14, 18, 31), clinical competency level, hospital accreditation (18), participating in pain management training courses, and reading books or journals in the field of pain, on the one hand, and the nurses' awareness and attitude on the other hand (31). Contrary to the results of these studies, the study by Lewthwaite et al. reported a negative correlation between the scores of awareness and attitude and the age and professional experiences of nurses (14).

5.1. Research Limitations

Concerning the fact that the nurses participating in the study were limited to select the predetermined options of the questionnaire, a more accurate examination of the participants’ attitude and level of knowledge was not possible. All the participants in this study were nurses working in adult general intensive care units. Therefore, the results of this study cannot be generalized to nurses working in other intensive care units, such as pediatric, neonatal, and surgical units.

5.2. Conclusions

Reviewing various texts show that the nurses’ knowledge of pain management and their attitudes toward it in patients hospitalized in ICUs are global issues and of great importance. Similarly, in the current study, investigating the nurses' awareness and attitude before and after the intervention indicated that teaching a comprehensive pain management program, as well as its practical and operational implementation, could be effective in enhancing the nurses’ knowledge and attitude. Moreover, an increase in ICU working experience is also effective in improving the nurses’ attitudes. Therefore, considering the results of the present study and other ones, it is proposed to utilize guidelines and practice patterns of pain management to promote the nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and effective performance in the field of pain management in intensive care units.