1. Background

Migraine is a neurovascular headache characterized by throbbing pain, mostly on one side of the head (1). It is the third common disease worldwide, with an estimated global prevalence of 14.7% (2). The duration of migraine attacks is varied and can be last for minutes to hours, reaching in some cases to days (3). However, most of the migraine patients exhibit recurrent attacks that are frequently associated with nausea, vomiting, as well as extreme sensitivity to sound and light (1). As such, migraine is more than a headache; it is a complex neurological disorder that affects many areas in the brain, including cortical, subcortical, and brainstem (4). Most commonly, the first attack of migraine starts in the early years of life (childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood), while most prevalent migraine attacks occur in the third and fourth decades of life (5). Migraine can progress through different stages; prodrome, aura, attack, and post-drome (6), and its symptoms significantly affect the patient’s life, productivity, social influence, and professional outcomes (7). Accordingly, migraine is considered as one of the important causes of disability, as noted by the Global Burden of Diseases and the World Health Organization in 2016 (8). Thus, many scoring systems were designed to evaluate migraine-associated disabilities, of which a Migraine Disability Assessment score (MIDAS) is a well-organized and standard questionnaire to assess the level of migraine pain concerning the severity of disabilities in the affected individuals (9).

Locally, migraine is a common disease in Saudi Arabia, while recent epidemiological studies regarding its associated disabilities still are limited and are mostly regional reports (10-13).

2. Objectives

In this study, we assessed disabilities in Saudi migraine patients using MIDAS score to relay the relationship between migraine-associated disabilities and social factors, including age, gender, marital status, number of kids, education level, and occupation as well as some specific habitats, such as regular exercise and smoking in different cities throughout Saudi Arabia.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design, Population, and Ethical Approval

This study was a cross-sectional web-based survey of adult migraine patients. The sample was recruited randomly by distributing the survey through social media applications to the general population in Saudi Arabia in March 2020. Migraine patients in Saudi Arabia were screened for eligibility based on their age (16 - 60), nationality (Saudi), and confirmed diagnosis of migraine by a health care professional. These three criteria were in the first part of the questionnaire and determined the eligibility of the participant to continue the survey. We considered the minimum sample size of 190 cases, which was estimated using the sample size equation (14) according to a recent Saudi migraine prevalence study published in February 2020 (25%) with a 90% level of confidence and a 5% margin of error (13). Since our survey was randomly distributed through social media, the response rate was impracticable to be calculated. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study before starting the survey. The study protocol and ethical approval were sanctioned by the Unit of Biomedical Ethics (Research committee, King Abdelaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; reference no.: 35-20).

3.2. Questionnaire and Assessment Scores Survey

The questionnaire was composed of three parts; in the first part, we asked about the general personal information (age, gender, nationality, and confirmation of migraine diagnosis), social information (marital status, number of kids if married, education level, and occupation), and special daily habits (regular exercise and smoking). In the second part, we asked about symptomatic and prophylaxis medications. MIDAS items were included in the third part of the survey to calculate the MIDAS score for each response as follows: grade I (0 - 5) little/no disability, grade II (6 - 10) mild disability, grade III (11 - 20) moderate disability, and grade IV (+ 21) severe disability (15). Besides, pain severity was divided into mild (0 - 4), moderate (5 - 6), and severe (7 - 10) pain.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

We presented our data as frequencies and percentages for descriptive statistics and investigated the outcomes using GraphPad Prism 8.4.1 software (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). We recorded age as a categorical variable (16 - 25, 26 - 35, 36 - 45, 46 - 55, more than 55 years) and gender as male or female. We classified marital status into married, single, divorced, or a widow; education level into illiterate, secondary level, bachelor, diploma, master, or PhD; and employment status into either currently employed or not working. We calculated the MIDAS score for each response and categorized it into an ordinal variable (I, II, III, and IV). The Chi-square test was used to analyze the association between the MIDAS grade, as an ordinal dependent variable, and independent categorical variables. A significant difference was assumed when P-value < 0.05.

4. Results

Among the 480 total responses, 250 (52%) participants were included based on eligibility criteria and the absence of missing data on their answers, of whom 208 cases (83.2%) were females. The mean age of participants was 34.84 ± 10.14 years. More than half of the participants were married (60%), had a bachelor’s degree (61%), and were employed (53%). About 83% of the participants were non-smokers, and only 16% performed regular exercise (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| 16 - 25 | 58 (23.2) |

| 26 - 35 | 83 (33.2) |

| 36 - 45 | 65 (26.0) |

| 46 - 55 | 31 (12.4) |

| > 55 | 13 (5.2) |

| Gender (females) | 208 (83.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 84 (33.6) |

| Married | 149 (59.6) |

| Divorced | 14 (5.6) |

| Widowed | 3 (1.2) |

| Number of kids | |

| Single or none | 99 (39.6) |

| 1-2 | 67 (26.8) |

| 3-4 | 58 (23.2) |

| ≥ 5 | 26 (10.4) |

| Educational level | |

| Secondary or diploma | 43 (17.2) |

| Bachelor | 152 (60.8) |

| Master | 33 (13.2) |

| PhD | 22 (8.8) |

| Occupation | |

| Currently employed | 132 (52.8) |

| Currently not employed | 118 (47.2) |

| Do regular exercises | 41 (16.4) |

| Do smoke | 42 (16.8) |

During the migraine attack, 34% of the subjects denied taking any medication, and more than half of them were never taking prophylaxis. The common medication used by migraineurs during the attack was acetaminophen, while amitriptyline was the most recall prophylaxis (Table 2). However, more than half of our participants had one or more attacks per week, and the majority of them were experiencing severe pain during a single attack (Table 2).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptomatic treatment | |

| None | 85 (34.0) |

| Acetaminophen | 44 (17.6) |

| Combined acetaminophen and NSAIDs | 34 (13.6) |

| Triptans | 30 (12.0) |

| NSAIDs | 25 (10.0) |

| Others | 32 (12.8) |

| Prophylaxis treatment = 87 | |

| Amitriptyline | 12 (13.8) |

| Beta-blocker | 10 (11.5) |

| Topiramate | 6 (6.9) |

| Botox injection | 4 (4.6) |

| Triptans | 3 (3.4) |

| Others | 24 (27.6) |

| Do not recall | 28 (32.2) |

| Regarding follow up and prophylaxis | |

| Never take prophylaxis because no follow up since diagnosis | 58 (23.2) |

| Never take prophylaxis because the physician did not prescribe | 105 (42.0) |

| Quit after taking prophylaxis for some time | 33 (13.2) |

| Taken but non-complaint | 9 (3.6) |

| Completed prophylaxis course as advised by the physician | 25 (10) |

| Currently on prophylaxis | 20 (8.0) |

| Severity of pain during attacks | |

| Mild (0 - 4) | 27 (10.8) |

| Moderate (5 - 6) | 49 (19.6) |

| Severe (7 - 10) | 174 (69.6) |

| Attack frequency | |

| Less than once per month | 45 (18.0) |

| 1 - 2 month | 72 (28.8) |

| Weekly | 59 (23.6) |

| > once week | 74 (29.6) |

Abbreviation: NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

On the MIDAS score, most subjects had a severe or mild disability (44.4% and 24.0%, respectively), while only 20% had little or no disability. The summarized scores and items of the MIDAS questionnaire are shown in Table 3.

| Median or No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| MIDAS items | |

| Days you miss school or work due to headache (in the last 3 months) | 1 |

| Days your work productivity reduced by half or more (in the last 3 months) | 3 |

| Days did not you household work (in the last 3 months) | 4 |

| Days your household productivity reduced by half or more (in the last 3 months) | 4 |

| Days did you miss family or social activities (in the last 3 months) | 2 |

| Days did you have a headache (in the last 3 months) | 7 |

| Average how painful were these headaches (on a scale 0 - 10) | 8 |

| MIDAS grade (N = 250) | |

| Little/no disability | 49 (19.6) |

| Mild disability | 30 (12.0) |

| Moderate disability | 60 (24.0) |

| Severe disability | 111 (44.4) |

4.1. The Relation Between MIDAS Grade and Different Variables

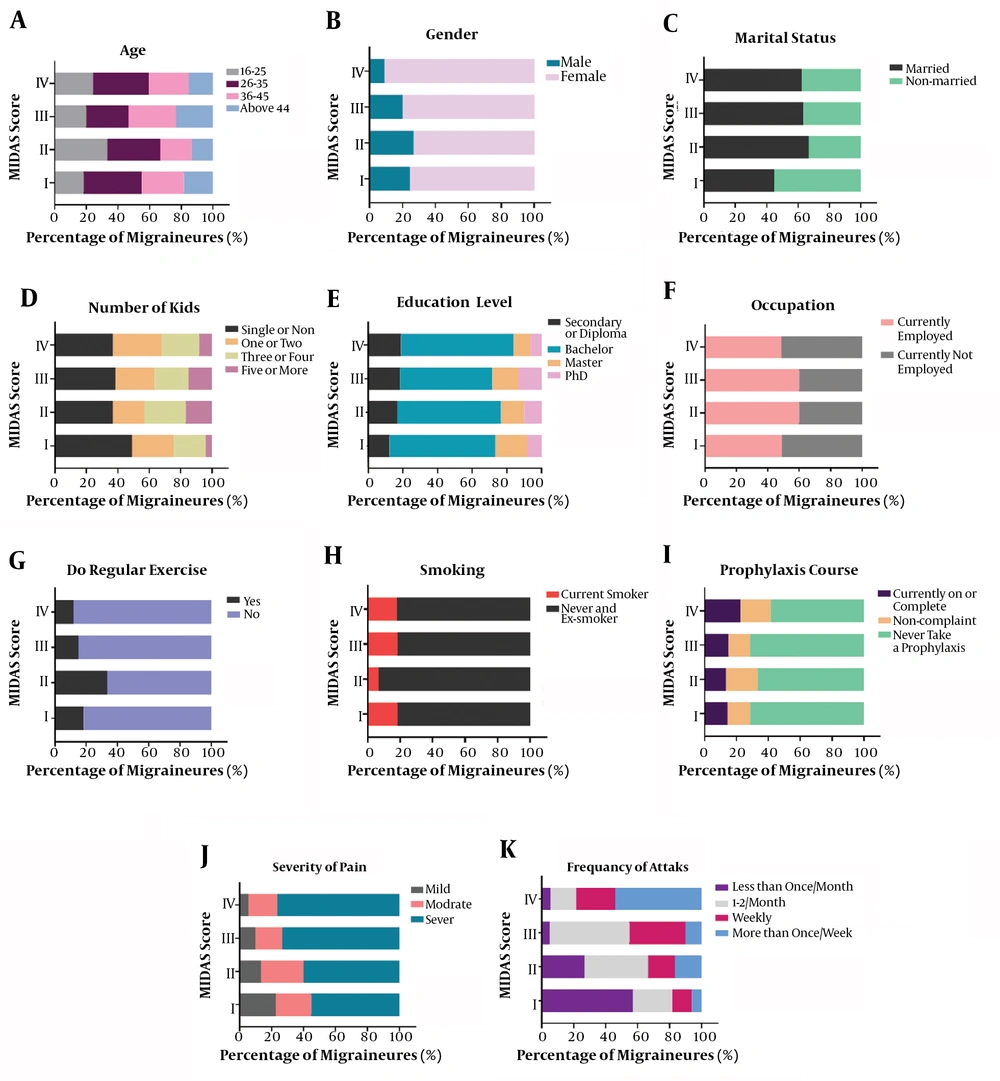

The association between MIDAS grades (I, II, III, or IV) and different categorical variables were measured using the Chi-square test, which revealed that gender and regular exercise had a statistically significant relationship with disability status among participants (P-value = 0.0242 and 0.0406, respectively). Females had a higher disability status, while regular exercise appeared to decrease the MIDAS score significantly. Other factors, including age, marital status, number of kids, education level, occupation, and smoking had no significant association with MIDAS grade in our selected patients (P-value = 0.7578, 0.1288, 0.5410, 0.7296, 0.4031, and 0.4737, respectively; Table 4). Moreover, no association was found between prophylaxis status and MIDAS grade (P-value = 0.5658; Table 4). However, greater pain severity and a higher number of attacks increased the disability status significantly; therefore, it affected the lifestyle routine (P-value = 0.0357, and < 0.0001, respectively; Table 4). Figure 1 summarizes the percentage of migraine patients in each MIDAS grade according to their different variables.

| Variables | MIDAS Score | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| Age, y | 0.7578 | ||||

| 16 - 25 (n = 58) | 9 (15.5) | 10 (17.2) | 12 (20.7) | 27 (46.6) | |

| 26 - 35 (n = 83) | 18 (21.7) | 10 (12.0) | 16 (19.3) | 39 (45.0) | |

| 36 - 45 (n = 65) | 13 (20.0) | 6 (9.2) | 18 (27.7) | 28 (43.1) | |

| > 45 (n = 44) | 9 (20.5) | 4 (9.1) | 14 (31.8) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Gender | 0.0242* | ||||

| Male (n = 42) | 12 (28.6) | 8 (19.0) | 12 (28.6) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Female (n = 208) | 37 (17.8) | 22 (10.6) | 48 (23.1) | 101 (48.6) | |

| Marital status | 0.1288 | ||||

| Married (n = 149) | 22 (14.8) | 20 (13.4) | 38 (25.5) | 69 (46.3) | |

| Non married (n = 101) | 27 (26.7) | 10 (9.9) | 22 (21.8) | 42 (41.6) | |

| Number of kids | 0.5410 | ||||

| Single or non (n = 99) | 24 (24.2) | 11 (11.1) | 23 (23.2) | 41 (41.4) | |

| One or two (n = 67) | 13 (19.1) | 6 (8.8) | 15 (22.1) | 34 (50.0) | |

| Three or four (n = 58) | 10 (17.2) | 8 (13.8) | 13 (22.4) | 27 (46.6) | |

| Five or more (n = 26) | 2 (8.0) | 5 (20.0) | 9 (36.0) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Education level | 0.7296 | ||||

| Secondary or diploma (n = 43) | 6 (14.0) | 5 (11.6) | 11 (25.6) | 21 (48.8) | |

| Bachelor (n = 152) | 30 (19.7) | 18 (11.8) | 32 (21.1) | 72 (47.4) | |

| Master (n = 33) | 9 (27.1) | 4 (12.1) | 9 (27.3) | 11 (33.3) | |

| PhD (n = 22) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) | 8 (36.4) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Occupation | 0.4031 | ||||

| Employed (n = 132) | 24 (18.2) | 18 (13.6) | 36 (27.3) | 54 (41.0) | |

| Not employed (n = 118) | 25 (21.2) | 12 (10.2) | 24 (20.3) | 57 (48.3) | |

| Doing regular exercise | 0.0406* | ||||

| Yes (n = 41) | 9 (22.0) | 10 (24.4) | 9 (22.0) | 13 (31.7) | |

| No (n = 209) | 40 (19.1) | 20 (9.6) | 51 (24.4) | 98 (46.9) | |

| Smoking | 0.4737 | ||||

| Yes (n = 42) | 9 (21.4) | 2 (4.8) | 11 (26.2) | 20 (47.6) | |

| No (n = 208) | 40 (19.2) | 28 (13.5) | 49 (23.6) | 91 (43.8) | |

| Prophylaxis course | 0.5658 | ||||

| Currently on or complete (n = 45) | 7 (15.6) | 4 (8.9) | 9 (20.0) | 25 (55.6) | |

| Non-complaint or non-complete (n = 42) | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 8 (19.0) | 21 (50.0) | |

| Never take a prophylaxis (n = 163) | 35 (21.5) | 20 (12.3) | 43 (26.4) | 65 (39.9) | |

| Severity of pain | 0.0357* | ||||

| Mild (n = 27) | 11 (40.7) | 4 (14.8) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Moderate (n = 49) | 11 (22.4) | 8 (16.3) | 10 (20.4) | 20 (40.8) | |

| Severe (n = 174) | 27 (15.5) | 18 (10.3) | 44 (25.3) | 85 (48.9) | |

| Attack frequency | < 0.0001*** | ||||

| < Once month (n = 45) | 28 (62.2) | 8 (17.8) | 3 (6.7) | 6 (13.3) | |

| 1 - 2 month (n = 72) | 12 (16.7) | 12 (16.7) | 30 (41.7) | 18 (25.0) | |

| Once weekly (n = 59) | 6 (10.2) | 5 (8.5) | 21 (35.6) | 27 (45.8) | |

| > Once week (n = 74) | 3 (4.1) | 5 (6.8) | 6 (8.1) | 60 (81.1) | |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bChi-square test was used to assess the differences between the categorical variables. * and *** revealed a significant difference.

5. Discussion

Migraine is a highly prevalent disorder in Saudi Arabia, as concluded by multiple studies done throughout various cities around the country (16, 17). From 2000 to 2017, the migraine had a persistent rise in the ranks of top causes of disability; started with the 19th cause of disability until the second cause of disability in 2017, as reported by the global burden of the diseases (18, 19). However, it is the first cause of disability in under 50 years old individuals (19). Migraine-related disabilities include difficulty in doing daily routine activities, a decrease in work performance, and interrupted personal social behaviors (7). In our study, we aimed to clarify the association between migraine disability status, using the MIDAS score, and different personal and social variables. In the MIDAS score, migraineurs were granted to answer five questions regarding their activity limitations due to headaches in the past three months to assess the effect of migraine on their daily activities (20). Headache frequency and migraine pain severity were also included in the MIDAS items (21). Our results demonstrated a significant association between MIDAS score and regular exercise. The regular exercise (30 to 40 min three times per week) was coupled with less functional disability status among migraineurs. However, exercise has been recommended widely as non-pharmacological management of persistent pain conditions involving migraine (22). Moreover, multiple large studies concluded that lower physical activity is related to the increased prevalence of several types of headaches, including migraine (22). Regular exercise could reduce the intensity and frequency of migraine attacks because of three important reasons; first, the endorphin, which considered as the natural painkillers has released during exercise. Second, because the exercise increases the nitric oxide level and consequently prevents the action of vasoconstrictors and free radicals, third because the exercise reduces the stress and has a positive effect on a regular lifestyle behavior of sleep, which both (stress and inadequate sleep) trigger the migraine attack (22-25).

Many studies have confirmed the direct effect of gender on the migraine prevalence, severity, intensity of attacks, and related disabilities, as females were found to have a higher degree in all considerations (7). In our study, migraine-related disabilities were also higher in female migraineurs compared with males. Our analyses also confirmed a strong association between worse migraine-related disabilities and the severity of pain as well as higher numbers of attacks, which was reported previously (21).

Regarding the education level, no relationship was detected between education level and MIDAS score in our study. However, previously conducted studies regarding the education factor gave dissimilar results. Higher education level was significantly associated with higher disability scores in some studies (26) and with lower disability scores in another (27). Our study also disowned marital status, number of kids, and occupation factors to have an association with MIDAS score as described in the literature.

Although many researchers have analyzed the relationship between smoking status and migraine, no exact relationship has been detected so far. The results behind this association were giving conflicting results; some studies have denied smoking to be a risk factor for the migraine etiology or exacerbation (28). Other studies have reported a higher prevalence of migraine among smokers than former or never smokers (29). Moreover, one study detected a connection between the development of a migraine attack and the number of cigarettes (30). Likewise, some studies have considered smoking as a participating factor to increase the migraine attack frequency and severity (31). The relationship between smoking and the patient’s gender was also observed, as female smokers believed to have more severe attacks (31). On the one hand, smoking increases the production of nitric oxide and platelet aggregability (32), and nicotine causes intracranial vasoconstriction leading to the reflex release of vasodilator metabolites, therefore, triggers a migraine attack (33, 34). On the other hand, light smoking increases the secretion of beta-endorphins leading to a reduction in pain and anxiety (31, 35). In the current study, our results denied any association between smoking and migraine-associated disabilities. Likewise, no relationship was detected between current prophylaxis intake, completed prophylaxis course, or never taking prophylaxis and migraine-related disabilities in our study. At the same time, many published evidence have confirmed the ability of prophylaxis to decrease migraine attack duration and frequency, resulting in improving the patients’ daily activities (36). However, more studies should be done to authenticate these results, as no exact questions were included regarding dosage, duration, and frequency of medications.

In conclusion, most of the participants had a severe disability, reflecting an aggressive point that needs further attention. A non-pharmacological approach, such as regular exercise, was found to be an important factor for the prevention of migraine-associated disabilities. This study contributes to the relevant literature by proving the outcomes of migraines on disability among the general population in Saudi Arabia. It is limited by the online method survey that restricted us from facing or contacting the participants directly.