1. Background

Head and neck cancers account for about five to seven percent of all cancers worldwide (1). The main treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Other treatments, such as gene therapy and hyperthermia, are also being used to treat cancer. Radiotherapy is one of the main therapies that is used sometimes alone and sometimes in combination with other therapeutic methods (2, 3). Despite invading and eliminating cancer cells, radiotherapy can also damage normal cells. During radiotherapy sessions, complications such as the destruction of taste buds, decreased function of salivary glands, oral mucositis, and peripheral neuropathy are inevitable.

Oral mucositis is described as an inflammation of the mucosa in the oral cavity, which is caused by the destruction of oral mucosal epithelial cells and growth suppression secondary to cancer treatment with radiotherapy or other treatments (4). Mucositis is considered to be one of the leading causes of severe pain in patients receiving head and neck radiotherapy. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate and manage the pain (5, 6). The oral mucosa is lined with squamous epithelium, beneath which is a fibrous connective tissue containing a large number of capillaries. Wound healing in the oral mucosa follows the process of vasoconstriction, blood clot formation, fibrin formation, inflammatory cell infiltration, cell proliferation, new vein production, and epithelial regeneration (7). Various supportive methods have been proposed to improve the symptoms of mucositis, which, regardless of their side effects, often relieve the symptoms to varying degrees (8).

Ozone (O3) is a highly reactive molecule made up of three oxygen atoms, first introduced in the 1840s, which has an unstable structure due to the mesomeric effect of this molecule (9). Ozone has been used in medicine for many years because it has antimicrobial properties, stimulates the immune system, detoxifies, and activates metabolic reactions. Recently, the use of ozone has been introduced in many fields of dentistry, the main applications of which include accelerating homeostasis, improving oxygen delivery to organs, and preventing the growth of bacteria. Ozone can also be used in a diversity of ways, such as gas, ozonated water, and gel solutions. The effectiveness of ozone in medicine and dentistry is potentially confirmed (10). Animal research has shown the positive effects of ozone on cancer cells. In these studies, ozone significantly increased the survival of study groups (11). In another study, Clavo et al. examined the effects of systemic ozone on patients with head and neck cancer who were being treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In all participants, oxygen delivery to the cancerous tissues increased significantly. The authors suggested the use of ozone for the treatment of patients receiving radiation therapy and chemotherapy (12). A review study stated that there are various supportive and palliative approaches for oral mucositis, although there is no confirmed standard (13). Previously, Onda et al. suggested ozone nano-bubble water for curing chemotherapy-induced stomatitis (14). The results of another review article showed that the allowable dose of ozonated water ranges from 3 to 2,100 ppm (in vitro and in vivo) (15). Besides, a concentration between 0.05 and 0.1 ppm has antimicrobial effects (16, 17).

2. Objectives

Since a few studies have been conducted on the effects of ozonated water on the treatment of mucositis, in this study, we intend to evaluate the effect of ozone-containing water on oral mucositis induced by radiation therapy.

3. Methods

This investigation is a single-center observational cross-sectional study conducted in 2019. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (No. 91002655). Ozonated water was produced by a HAB generator (Herrmann Apparatebau GmbH, Germany). Based on the institutional protocol, some patients received ozonated water as a preemptive agent. This was not mandatory, and patients were educated about the benefits and harms. We randomly selected 93 patients (with head and neck malignancies) in three groups. The criteria for entering the study included patients with head and neck malignancies who did not need resection surgery, age between 18 and 80, and weight of less than 100 kg. The minimum planned dose for each patient was 50 Gray (Gy). The dosage of radiation was aligned with previous clinical trials (18, 19). The minimum number of radiotherapy sessions was 30. Exclusion criteria were patients who could not complete the study (due to death, another illness, etc.), the need for surgery during the study, and known sensitivity to ozone or its smell.

Ozone-treated group 1 rinsed their mouth with 15 mL of ozonated water with a concentration of 20 - 50 ppm for one minute before and after each session of radiotherapy from the first session. Ozone-treated group 2 rinsed their mouth with 15 mL of ozonated water with a concentration of 20 - 50 ppm for three minutes and then swallowed it before and after each session. Ozone-treated groups 1 and 2 and the non-ozone-treated group received standard treatment if mucositis symptoms appeared in each patient. Standard treatment consisted of symptomatic treatment with normal saline mouthwash, diphenhydramine mouthwash, pilocarpine salivary enhancer, and antibiotic therapy. In the beginning, the health of the patients' teeth and mucous membranes was ensured by a clinician after oral examinations. Patients were encouraged to maintain good oral hygiene, including brushing and flossing. Patients were barred from using commercial mouthwashes.

The sample size was calculated based on the results of a pilot study (20-22). We chose an alpha error of 5%. To reach a power of 80% with an estimated effect size of 0.30, a sample of 31 participants for each group was calculated.

The severity of the pain was reported by patients according to a Pain Visual Analogue Scale (PVAS) (1 to 10 scores). The condition of the mucosa was assessed based on the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Grading (RTOG) scale for oral mucositis, which is listed in Table 1 (23, 24). Also, the method of radiotherapy and the dose of radiation each patient received were compared between the groups. The evaluations were performed by a trained clinician in session 5, session 10, session 15, session 20, session 25, and session 30 of radiation therapy. Standard treatment was prescribed in all groups if grade 2 or higher of mucositis occurred or if the pain interfered with swallowing and normal speech. Statistical analysis of data was done with the t-test and the Mann-Whitney test using SPSS 26.0 software.

| Grade | RTOG Scale |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Normal mucosa without mucositis |

| Grade 1 | Mild inflammation with a slight pain that does not require anesthesia |

| Grade 2 | Mucositis in the form of a patch that is associated with secretions and requires anesthesia |

| Grade 3 | Disseminated mucositis and severe pain |

| Grade 4 | Wounds, bleeding, and necrosis |

| Grade 5 | Death |

4. Results

In the present study, background characteristics, including sex, age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and corticosteroid intake, were analyzed. None of the background characteristics were significantly different between the three study groups (P-value > 0.05; Table 2). Also, the radiation dose and radiotherapy method were not statistically different between the groups (P-value > 0.05). The background characteristics of the study groups are provided in Table 2.

| Patients | Total | Control | Ozone-treated 1 | Ozone-treated 2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 93 (100) | 31 | 31 | 31 | |

| Gender | 0.25 | ||||

| Male | 57 (61.3) | 20 (64.5) | 20 (64.5) | 17 (54.8) | |

| Female | 36 (38.7) | 11 (35.5) | 12 (35.5) | 14 (45.2) | |

| Age | 93 (50.81) | 31(50.64) | 31(51.19) | 31(50.61) | 0.79 |

| Smoking | 0.44 | ||||

| Yes | 35 (37.6) | 12 (38.7) | 12 (38.7) | 11 (35.5) | |

| No | 58 (62.4) | 19 (61.3) | 19 (61.3) | 20 (64.5) | |

| Diabetes | 0.34 | ||||

| Yes | 29 (31.2) | 10 (32.3) | 11 (35.5) | 8 (25.8) | |

| No | 64 (68.8) | 21 (67.7) | 20 (64.5) | 23 (74.2) | |

| Corticosteroid | 0.41 | ||||

| Yes | 8 (8.6) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) | 2 (6.5) | |

| No | 85 (91.4) | 28 (90.3) | 28 (90.3) | 29 (93.5) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

The highest grade of mucositis observed in the study groups was grade 3, which was observed in 10 patients of the non-ozone-treated group, one patient in ozone-treated group 1, and no patient in ozone-treated group 2 (Table 3).

| Groups | Non-ozone-treated | Ozone-treated 1 | Ozone-treated 2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | |

| First session | 0.32 | |||

| Grade 0 | 29 (93.5) | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | |

| Grade 1 | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Fifth session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 11 (35.5) | 28 (90.3) | 31 (100) | |

| Grade 1 | 20 (64.5) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 10th session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 5 (16.1) | 22 (71) | 30 (96.8) | |

| Grade 1 | 26 (83.9) | 9 (29) | 1 (3.2) | |

| 15th session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (25.8) | 18 (58.1) | |

| Grade 1 | 25 (806.) | 23 (74.2) | 13 (41.9) | |

| Grade 2 | 6 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 20th session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Grade 1 | 16 (51.6) | 27 (87.1) | 25 (83.3) | |

| Grade 2 | 15 (48.4) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 25th session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Grade 1 | 6 (19.4) | 24 (77.4) | 28 (93.3) | |

| Grade 2 | 24 (77.4) | 5 (16.1) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 30th session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Grade 1 | 0 (0.0) | 13 (41.9) | 22 (73.3) | |

| Grade 2 | 21 (67.7) | 16 (51.6) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Grade 3 | 10 (32.3) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| First to 30th session | 0.000 | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Grade 1 | 2 (6.5) | 13 (41.9) | 22 (73.3) | |

| Grade 2 | 19 (61.3) | 16 (51.6) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Grade 3 | 10 (32.3) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

In terms of oral mucositis grading (Table 3), there was no statistical difference between the three groups of patients in session 1. However, from sessions 5 to 30, there was a statistically significant difference between the three groups of patients so that patients in ozone-treated group 2 had a lower grade of mucositis than patients in ozone-treated group 1 and the non-ozone-treated group. In the 15th session and thereafter, all non-ozone-treated patients had some degree of oral mucositis. In the 30th session, more than one-third of these patients had grade 3 of oral mucositis. In contrast, none of the patients in ozone-treated group 2 had grade 3 of mucositis. One case of grade 3 of mucositis was seen in ozone-treated group 1.

The Mann-Whitney test showed that in all sessions, the severity of mucositis was higher in the non-ozone-treated group than in the ozone-treated groups (P < 0.05). Also, the severity of mucositis was significantly higher in patients of ozone-treated group 1 than in patients of ozone-treated group 2 (P-value < 0.05; Table 4).

| Sessions | Non-ozone-treated | Ozone-treated 1 | Ozone-treated 2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-30th | 2.2 ± 0.57 | 1.5 ± 0.62 | 1.2 ± 0.44 | < 0.05 |

aValues are expressed as Mean ± SD.

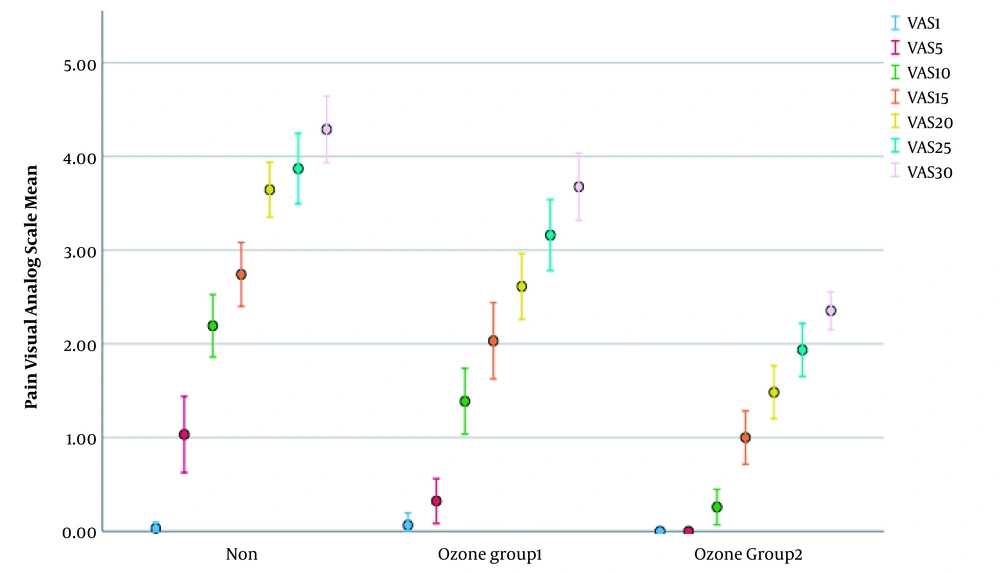

The severity of the pain reported by the patients was recorded in sessions 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25, as well as the end of radiotherapy in the non-ozone-treated group and the recipients of ozonated water. The results are shown in Table 5. The Kruskal-Wallis H test showed that the non-ozone- treated group significantly had the most pain scores, followed by ozone-treated group 1 and ozone-treated group 2 groups in most of the secessions except the first session (P > 0.05). It means that session fifth to the 30th season, non-ozone-treated patients experienced more severe pain than ozone-treated patients.

The Kruskal-Wallis H test also showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the Visual Analog Scale scores in sessions 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 between the different groups (Table 5). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the Visual Analog Scale score in session 1 (χ2 (2) = 1.022, P = 0.6).

| Groups | Mean Rank | χ2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5th session | 22.297 | < 0.0005 | |

| Non-ozone-treated | 60.34 | ||

| Ozone-treated 1 | 45.16 | ||

| Ozone-treated 2 | 35.50 | ||

| 10th session | 40.917 | < 0.0005 | |

| Non-ozone-treated | 67.85 | ||

| Ozone-treated 1 | 50.48 | ||

| Ozone-treated 2 | 22.66 | ||

| 15th session | 23.742 | < 0.0005 | |

| Non-ozone-treated | 65.35 | ||

| Ozone-treated 1 | 49.66 | ||

| Ozone-treated 2 | 25.98 | ||

| 20th session | 33.741 | < 0.0005 | |

| Non-ozone-treated | 70.05 | ||

| Ozone-treated 1 | 47.69 | ||

| Ozone-treated 2 | 23.26 | ||

| 25th session | 31.282 | < 0.0005 | |

| Non-ozone-treated | 65.71 | ||

| Ozone-treated 1 | 51.11 | ||

| Ozone-treated 2 | 24.18 | ||

| 30th session | 45.208 | < 0.0005 | |

| Non-ozone-treated | 66.05 | ||

| Ozone-treated 1 | 53.42 | ||

| Ozone-treated 2 | 21.53 |

As vividly appeared in Table 5, ozone-treated group 2 patients reported lower pain scores in all sessions than patients in the two other groups. Patients in group 1 experienced less pain in all sessions than non-ozone-treated patients but more than patients in group 2. Finally, non-ozone-treated patients reported more severe pain than ozone-treated groups 1 and 2.

The reported PVAS scores were gradually increased over time (Figure 1). However, the increment was sharper for the non-ozone treated group than for the other groups.

5. Discussion

In the present study, the degree of oral mucositis differed significantly in all the evaluated sessions between the study groups (P < 0.05), except for the first session (P > 0.05). Ozone-treated groups had a lower degree of oral mucositis than the non-ozone-treated group (P < 0.05). In addition, the severity of pain was significantly lower in the ozone-treated groups (P < 0.05). Also, exposure to a higher amount of ozonated water resulted in a lower degree of mucositis and pain in the oral cavity, as observed in the ozone-treated group 2 that rinsed their mouth with ozonated water for three minutes and then swallowed it. During the study, only one patient from ozone-treated group 2 was excluded from the study in session 15 because of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This was aligned with previous studies that showed the potential efficacy of ozonated water for pain reduction (25) and preemptive agents (chemotherapy-induced toxicity) (26). The positive effects of ozonated water in periodontitis have been shown in previous studies (27, 28). Furthermore, it was revealed that ozone therapy can be applied to periodontal therapy (29).

The local factors interfering with this healing process are lack of oxygen supply, local infection, and the presence of foreign bodies. Systemic factors that may be influential include age, gender, circulatory disorders, immune condition, nutritional status, systemic disease, concomitant use of drugs such as steroids, and anti-cancer drugs (30). At the cellular level, exposure to ionizing radiation leads to the generation of free radicals (reactive oxygen species and active nitrogen species), breakage of DNA, and activation of transcription factors nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB). Besides, immune cells produce anti-inflammatory cytokines that exacerbate tissue damage and cell death (tumor necrosis factor [TNF-α], interleukin-1 [IL-1], and IL-6) (31).

Head and neck malignancies account for four to five percent of all malignancies and are more common in men over 40 years of age. Due to the severity and extent of malignancies in this area, treatment includes lesion surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation (32). Radiation can be associated with atrophy, inflammation, and atypical epithelial cells as mucositis. Oral mucositis is a condition of inflammation, redness, and mouth ulcers that can be accompanied by pain, difficulty swallowing, and difficulty speech. At the same time, it increases the risk of bacterial and fungal infections (33). Cancer-induced mucositis is defined as secondary mucosal damage due to cancer treatment with radiation therapy or chemotherapy. This condition can be toxic, severe, dose-dependent, debilitating, and is usually delayed by cancer treatment (34). The risk of oral mucositis due to cancer treatment has been reported to be 100% among patients receiving radiation therapy in the head and neck area (7).

New therapies for mucositis are now emerging. Sheibani et al. looked at the effects of benzydamine mouthwash to relieve the symptoms of radiation-induced mucositis. They showed that mouthwash was well tolerated by patients, and after four weeks of use, the symptoms reported in the placebo group were higher than in the benzydamine mouthwash group (35). Pawar et al. studied the effect of Samital, a plant product, on oral mucositis caused by chemo/radiotherapy. Their results showed that from day 31 until the end of treatment, Samital reduced symptoms and pain caused by mucositis, but no significant differences were observed between the groups (20). Various studies have evaluated the sedative effects of antidepressants on mucositis. These drugs, such as amifostine, vitamin E, polyphenols, tempol (from nitric oxide), and zinc, by reducing free radicals, can lead to the improvement and reduction of various symptoms (36). However, the results are somewhat inconsistent, and more comprehensive studies are needed to obtain further evidence. MuGard or mucoadhesive hydrogel is another product that has been used to treat oral mucositis in patients receiving radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the head and neck area. MuGard use in the study conducted by Allison showed to delay the progression of mucositis. In this study, MuGard was compared with the non-ozone treatment group that used sham control rinse (21). The most common treatment today is supportive therapy to relieve symptoms. Rinsing the mouth with normal saline serum, salivary enhancers such as pilocarpine and also diphenhydramine is usually prescribed to reduce mucosal pain (7).

The effect of ozone-containing oils on fibroblast migration to wound-healing was demonstrated so that the use of ozone for 12 days, every two days, by activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, led to an increase in fibroblast migration (22). Ripamonti used ozone-containing oils to treat osteonecrosis of the jaw caused by the use of bisphosphonates. It was shown that 10-min use of ozone three to 10 times a day for 10 days eliminated the effects of osteonecrosis and restored the structure of the mouth to normal (37). Günaydın examined the effect of ozone cytotoxicity on the l929 cell class. The use of ozone at concentrations of 2900 - 2700 mL equivalent of peroxide on this cell category derived from neoplastic mouse fibroblasts did not result in cell death. But, higher concentrations led to cell death, which was statistically significant. Finally, it was concluded that the short-term use of ozone did not have cytotoxic effects (38). This finding proves the safety of ozone in medical uses. Clavo et al. co-administered ozone locally with radiotherapy in patients with prostate cancer. In this group, rectal bleeding, which is a common complication in these patients, was significantly reduced. Clavo et al. looked at the effects of systemic ozone on patients with head and neck cancer who were on radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In all participants, oxygen delivery to the cancerous tissue increased significantly. They suggested the use of ozone in the treatment of patients receiving radiation therapy and chemotherapy (12).

5.1. Limitations

In this study, ozonated water therapy was used at the request of patients to spin water in their mouth for one minute in ozone-treated group 1 and three minutes in ozone-treated group 2 before and after each radiotherapy session for 30 sessions. One of the disadvantages of this study is that there was no specific or standard way to use ozone therapy in the oral cavity. Therefore, there is a need for a precise method of administration of ozone in the oral cavity. Also, more samples and a longer study period could help achieve more reliable results. Specifying the malignancy type also may be advantageous. It is also advised to compare ozone with other supportive and therapeutic methods for mucositis, such as laser therapy. Finally, more randomized clinical trials and cohort studies are needed to confirm the results of this study.

5.2. Conclusions

The use of ozonated water in patients with head and neck malignancy can reduce the pain severity and oral mucositis induced by radiotherapy. More exposure to ozonated water and also swallowing it was more effective. In general, patients who used ozonated water during radiotherapy sessions felt less discomfort in the oral cavity. Therefore, it seems that ozonated water can be considered a preemptive agent for pain and mucositis.