1. Background

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019 sparked a global health crisis of unprecedented proportions, giving rise to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (1). Initially identified in the city of Wuhan, China, COVID-19 swiftly spread across international borders, prompting widespread concern and stringent containment measures (1).

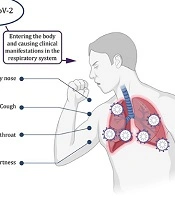

Common symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection encompass a range of respiratory and systemic manifestations (2). Patients afflicted by the virus often present with symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, fever, fatigue, and headache (Figure 1) (2). Additionally, some individuals have reported gastrointestinal symptoms or anosmia (loss of smell) (2). It is essential to acknowledge that the severity of COVID-19 can vary significantly, spanning from mild cases akin to the common flu to severe illness and, tragically, fatalities (2).

In the realm of infectious diseases, COVID-19 has been classified as a self-limiting affliction, with most individuals experiencing mild symptoms typically recovering within one to two weeks (3). However, the outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection can be diverse, culminating in five different scenarios: Asymptomatic infection, mild to moderate cases, severe cases, critical cases, and death (4). Recent research even suggests that children under the age of 20 years might exhibit a relatively high proportion of asymptomatic infections (5).

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, each country grappled with the virus’s unique impact, leading to distinct statistics and outcomes. Notably, the United States, at a certain point, documented the highest number of COVID-19 cases, deaths, and overall mortality rate in the Americas and globally (6). The United States reported a staggering 103,436,829 confirmed cases and 1,138,309 deaths, corresponding to a mortality rate of 1.09%. On the other hand, China reported 99,319,332 confirmed cases and 121 781 deaths, resulting in a considerably lower mortality rate of 0.12% (6). These statistics underscore the variability in COVID-19’s severity and mortality rates across different regions and nations.

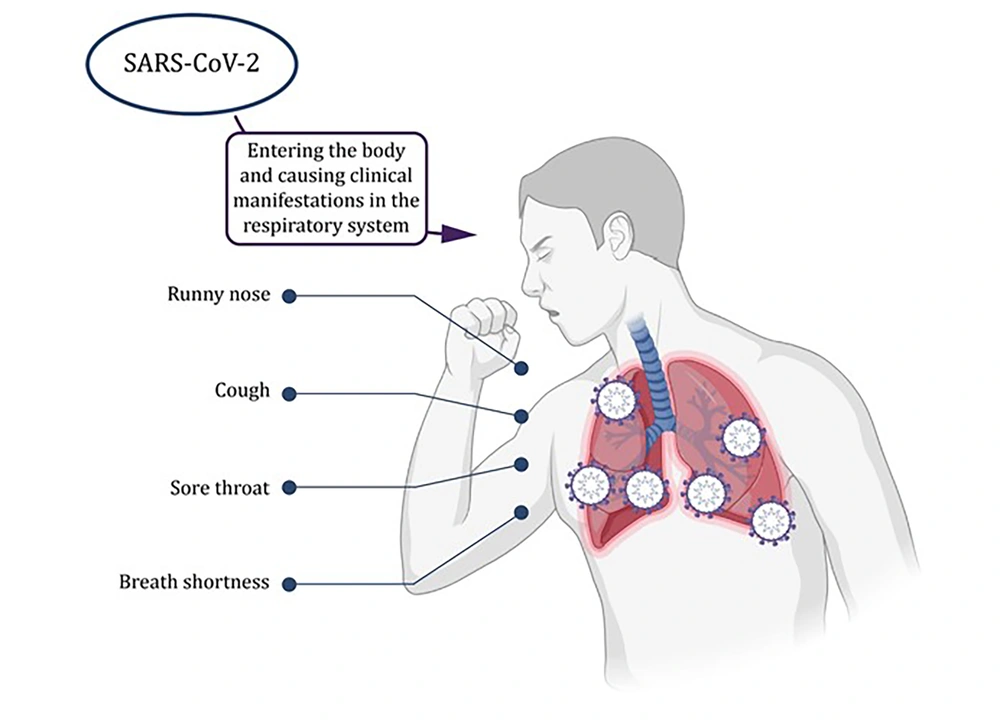

However, the impact of SARS-CoV-2 extends beyond the realm of respiratory illnesses, as it has been implicated in a spectrum of neurological disorders (NDs), posing an additional layer of complexity to the pandemic’s toll on public health (Figure 2) (7). Neurological disorders, characterized by various cognitive, motor, and sensory impairments, are already recognized as a significant public health challenge (8). These conditions often result from complex interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental factors (9).

The intriguing connection between SARS-CoV-2 and NDs becomes apparent when we delve into the neurological phenomena associated with COVID-19. Studies have reported neurological symptoms in a substantial percentage of pediatric COVID-19 patients, including headaches (10). Among children diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status and encephalopathy, have been observed (11, 12). Furthermore, severe neurological complications, including seizures, coma, encephalitis, demyelinating disorders, and aseptic meningitis, have been documented in a subset of pediatric MIS-C cases (13). Even infants and toddlers with COVID-19 have exhibited encephalopathy-like symptoms (14). However, neurological manifestations are not limited to pediatric cases; they have also been noted in adults during the acute phase of COVID-19. These manifestations encompass a wide array of symptoms, including headache, altered mental status, seizures, and stroke (15). Intriguingly, a proportion of infected individuals develop post-infectious viral syndromes characterized by diverse neuropsychiatric symptoms (15).

To understand the mechanisms underlying these neurological complications, it is essential to explore how SARS-CoV-2 might potentially infiltrate the central nervous system (CNS). The virus’s structure, encased within a nucleocapsid and surrounded by a nuclear envelope, offers insight into its potential neuroinvasive capabilities (16). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 can enter the CNS through multiple routes, including the general circulation, nasal cavity, and cribriform plate (16, 17). Once inside, the virus can interact with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on neurons, glia, endothelial cells, and other neural components, potentially causing neuronal damage and disrupting the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (16, 17). Such disruptions in the BBB might lead to cerebral edema, compromising vital respiratory functions (16).

Although the BBB is designed to prevent pathogen infiltration, neurotropic viruses have devised various strategies to breach this barrier (18). The hematogenous route, involving viremia and subsequent transcytosis or infection of endothelial cells, is one common pathway (19). Additionally, viruses can exploit infected monocytes as a “Trojan Horse” mechanism or enter the CNS through the coordination of motor or sensory nerves (19). Olfactory sensory neurons also serve as potential routes for many viruses to access the CNS (20).

Neurological complications following COVID-19 encompass a broad spectrum of symptoms, including headaches, ataxia, seizures, loss of taste and smell, vision impairment, and nerve pain (21). Furthermore, severe complications, such as polyneuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), meningitis, encephalitis, encephalopathy, cerebral hemorrhage, and infarction have been observed in some cases (21). This dynamic interplay between age and symptomatology adds an extra layer of complexity to our understanding of COVID-19’s neurological effects.

Psychological stressors have long been recognized as potential triggers for migraine episodes in pediatric patients (22, 23). The overwhelming emotional challenges, especially in educational environments, can lead to heightened central nervous system responses, increasing the risk of headaches and migraines (24). The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced new dimensions to the study of migraines. Research conducted during the pandemic reported fewer migraine attacks and lower pain levels among subjects with migraines, in addition to moderate levels of depression (25). The aforementioned findings underscore the intricate relationship between psychological stress, migraines, and the broader impact of the pandemic on individuals’ physical and mental well-being.

Moreover, the pandemic has cast a profound shadow on individuals with severe mental illnesses (SMIs), including bipolar disorders (BDs) (26). Lockdowns and social distancing regulations have disrupted social support systems, increased loneliness, and disrupted circadian rhythms (27, 28). For those already living with BD and related conditions, the burden of these downstream consequences has been particularly significant. Bipolar disorder, in particular, is a well-established risk factor for suicidality, and the pandemic’s socioeconomic impact might have exacerbated this risk (29-31). The pandemic’s far-reaching effects have also reshaped the landscape of care for individuals, leading to dramatic changes in telepsychiatry legislation (32).

Furthermore, the interplay between COVID-19 and schizophrenia, another prevalent mental health condition, cannot be ignored. Coronavirus disease 2019’s greater impact on older individuals and those with comorbidities holds substantial implications for schizophrenia patients, given their higher rates of comorbid conditions, including diabetes and pulmonary diseases (33). These patients are also more likely to smoke, further complicating their respiratory health (33). In general, schizophrenia patients are more susceptible to a higher risk of acute organ dysfunction and death upon admission and in the intensive care unit (ICU) (34).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate patients who have tested positive for COVID-19, alongside those diagnosed with BD, migraine, Alzheimer’s, and schizophrenia, to explore the intricate intersections of these conditions and their potential impact on individuals’ health and well-being.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Extraction

3.1.1. Demographic Data

The study encompassed a total of 63 participants with varying diagnoses: 7 individuals with schizophrenia, 8 with BD, 6 with migraine, and 12 with Alzheimer’s. Additionally, there was a group consisting of 30 subjects without an underlying neurological disorder but with a positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2. All relevant information from patients’ files was extracted.

3.1.2. Data Extraction

The study was conducted across 12 hospitals under the auspices of the Iranian Network for Research in Viral Diseases, including facilities such as Ali Asghar, Amin, Amiral Momenin, Imam Khomeini, Hajar, Khansari, Razi, Rouhani, Shariati, Sina, Vali Asr, and Yas Medical Center. Data collection spanned from March 2020 to May 2021, and patient information was retrieved from their medical records. Before participation, each patient provided informed consent, and the study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.TUMS.VCR.REC. 1399.599).

3.1.3. Statistical Methods

In this study, frequencies and percentages were used to describe different aspects of the data. The Chi-squared test was applied for independence, and the contingency coefficient, a chi-squared-based test for association, was employed to investigate the existence of any association between COVID-19 symptoms and different disease groups. All computations were performed using the IBM SPSS statistical package (version 27).

4. Results

This study examined a cohort of 63 COVID-19-infected patients, comprising 32 females (50.8%) and 31 males (49.2%). Among the individuals, 7 cases (11.1%) had schizophrenia, along with 8 cases (12.7%) with BD. Additionally, 6 patients (9.5%) reported migraine and 12 subjects (19%) were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. A group of patients without an underlying neurological disorder, consisting of 30 subjects (47.6%), had none of the aforementioned conditions but tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Notably, the gender distribution did not show significant differences across the five subgroups (chi-square test value = 4.628, P = 0.328).

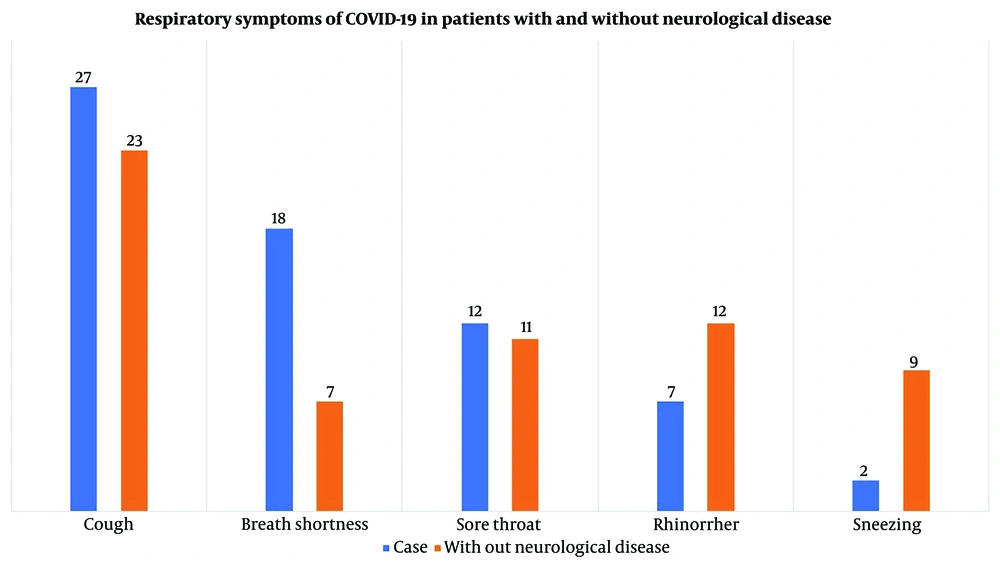

Table 1 shows the symptoms of COVID-19 observed in both the entire sample and within each subgroup. Across the entire sample, cough was the most prevalent symptom, affecting over 79% of the subjects. Fever ranked as the second most common symptom, experienced by approximately 62% of individuals. Fatigue followed closely as the third most reported symptom, affecting 57% of the subjects. Conversely, vomiting was the least frequently reported symptom, occurring in only 14.3% of cases.

| Symptom | Schizophrenia (n = 7) | Bipolar (n = 8) | Migraine (n = 6) | Alzheimer (n = 12) | Non-neurologic Disorder (n = 30) | Total (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | 6 (85.7) | 6 (75) | 5 (83.3) | 10 (83.3) | 23 (76.7) | 50 (79.4) |

| Fever | 4 (57.1) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (66.7) | 7 (58.3) | 21 (70) | 39 (61.9) |

| Fatigue | 2 (28.6) | 2 (25) | 3 (50) | 7 (58.3) | 22 (73.3) | 36 (57.1) |

| Headache | 5 (71.4) | 4 (50) | 4 (66.7) | 10 (83.3) | 7 (23.3) | 30 (47.6) |

| Anorexia | 3 (42.9) | 4 (50) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (50) | 13 (43.3) | 28 (44.4) |

| Breath shortness | 2 (28.6) | 4 (50) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (58.3) | 7 (23.3) | 25 (39.7) |

| Dizziness | 4 (57.1) | 2 (25) | 5 (83.3) | 10 (83.3) | 4 (13.3) | 25 (39.7) |

| Sore throat | 3 (42.9) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | 11 (36.7) | 23 (36.5) |

| Muscle pain | 4 (57.1) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | 10 (33.3) | 23 (36.5) |

| Lethargy | 2 (28.6) | 2 (25) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (50) | 8 (26.7) | 22 (34.9) |

| Rhinorrhea | 2 (28.6) | 2 (25) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) | 12 (40) | 19 (30.2) |

| Sleep problem | 5 (71.4) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (16.7) | 19 (30.2) |

| Nausea | 3 (42.9) | 2 (25) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (25) | 5 (16.7) | 14 (22.2) |

| Lack of taste | 3 (42.9) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (33.3) | 5 (16.7) | 13 (20.6) |

| Lack of smell | 1 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (25) | 7 (23.3) | 12 (19) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (28.6) | 2 (25) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (13.3) | 11 (17.5) |

| Sneezing | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | 9 (30) | 11 (17.5) |

| Vomiting | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) | 5 (16.7) | 9 (14.3) |

Investigated Symptoms of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Participants Divided by Neurologic Underlying Disorder Compared to Healthy Individuals a

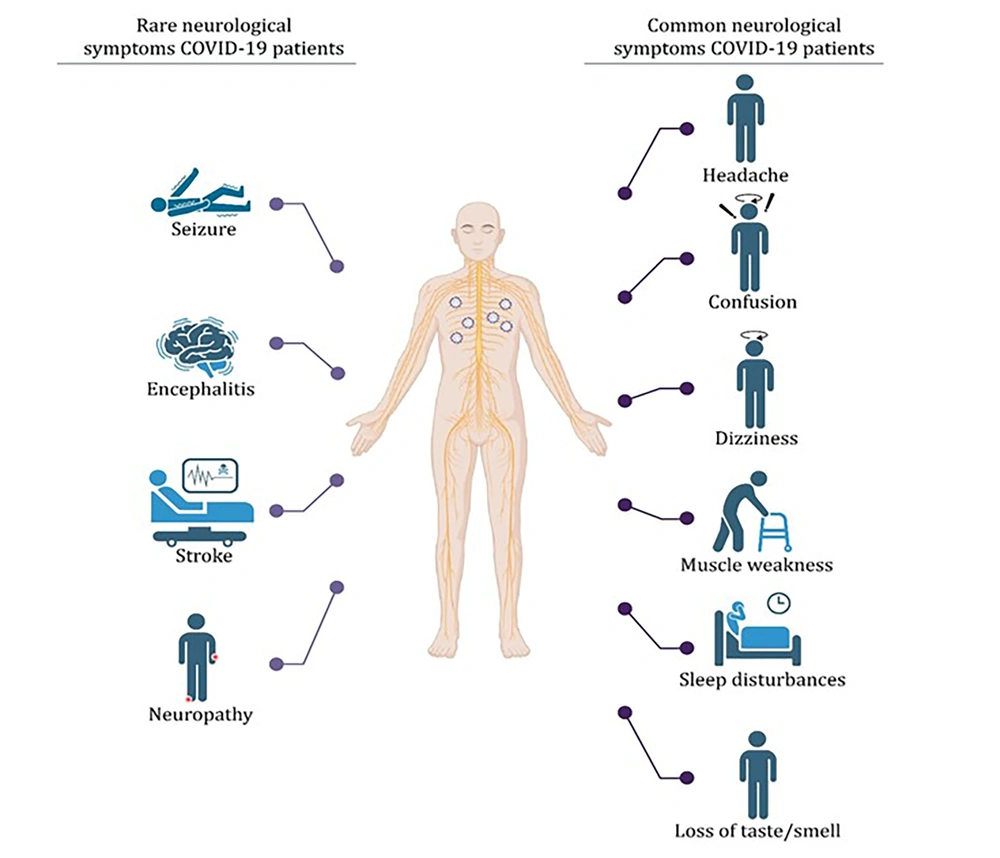

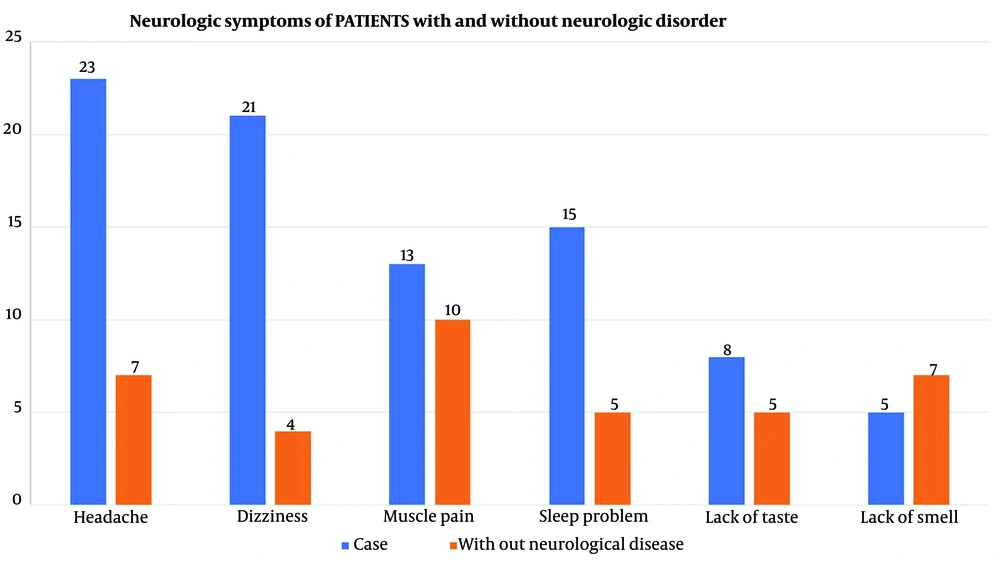

Table 2 shows the findings regarding the potential correlation between experiencing COVID-19 symptoms and different subgroups. The contingency coefficient for headaches was calculated as 0.447, with a P-value less than 0.05, indicating a significant association between subgroup membership and experiencing headaches. Notably, patients without an underlying disorder exhibited a notably lower proportion of individuals reporting headaches than the other four groups, as indicated in Table 1. Furthermore, statistically significant associations were observed for breath shortness (P = 0.032), dizziness (P < 0.001), and sleep problems (P = 0.030), with contingency coefficients suggesting notable links between experiencing these symptoms and subgroup membership. This finding suggests that individuals in various subgroups, including those experiencing breath shortness, sleep problems, dizziness, and headaches, were significantly more likely to report these symptoms in the context of COVID-19 infection. Associated symptoms stratified by neurological comorbidities are shown in Figure 3, and neurologic and respiratory symptoms of each group are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Neurologic symptoms might be due to underlying neurological disorders in Alzheimer’s, BD, migraine, and schizophrenia; nevertheless, respiratory symptoms are attributed to COVID-19. However, there might be an elevated risk of these symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Symptoms | Test Value a | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cough | 0095 | 0.966 |

| Fever | 0.215 | 0.550 |

| Fatigue | 0.354 | 0.060 |

| Headache | 0.447 | 0.003 b |

| Anorexia | 0.095 | 0.966 |

| Breath shortness | 0.379 | 0.032 b |

| Dizziness | 0.530 | < 0.001 b |

| Sore throat | 0.057 | 0.995 |

| Muscle pain | 0.152 | 0.827 |

| Lethargy | 0.277 | 0.254 |

| Rhinorrhea | 0.215 | 0.550 |

| Sleep problem | 0.382 | 0.030 b |

| Nausea | 0.194 | 0.652 |

| Lack of taste | 0.283 | 0.243 |

| Lack of smell | 0.190 | 0.668 |

| Diarrhea | 0.141 | 0.865 |

| Sneezing | 0.316 | 0.137 |

| Vomiting | 0.155 | 0.817 |

Test for Existence of Any Association Between Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms and Subgroups

5. Discussion

This study examined a sample comprising 7 individuals with schizophrenia, 8 cases of BD, 6 individuals with migraines, and 12 cases of Alzheimer’s disease. The findings revealed that cough had the highest prevalence at 79% among clinical symptoms, followed by fever at 62% and fatigue at 57%. Additionally, neurological symptoms, such as headaches, were prevalent in 56.25% of the cases, and sleep problems affected 46.87%, both showing significant occurrence rates.

Coronavirus disease 2019, caused by the novel coronavirus, can exhibit diverse neurological symptoms, including headaches, loss of taste and smell, confusion, and, in severe cases, strokes and encephalitis. Understanding and monitoring these symptoms is crucial for comprehensive patient care. In a study focused on neurological symptoms among a cohort of 891 individuals, the findings showed that headaches were prevalent in 63.9% of cases, sleep disturbances affected 51.3%, hyposmia/anosmia was observed in 46%, and dizziness occurred in 45.4%, establishing them as the predominant neurological symptoms in the studied population. The aforementioned results indicate differences from the present study, which reported lower rates of headaches and sleep disturbances but higher rates of dizziness in comparison (35).

Moreover, in an unrelated study focusing on neurological symptoms in 841 individuals diagnosed with COVID-19, it was discovered that 57.4% of these patients displayed neurological symptoms. Among these symptoms, myalgias were the most prevalent at 17.2%, followed by headaches at 14% and dizziness at 6.1%. These results starkly contrast with the results of the present study, where there were headache and dizziness occurrence rates of 56% and 65%, respectively, indicating a significant variation in the prevalence of neurological symptoms between the two studies (36).

Research indicates that individuals with pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic respiratory illnesses, have a higher risk of experiencing severe COVID-19 symptoms. These underlying health issues can worsen the virus’s physiological processes, resulting in heightened inflammation, immune system dysfunction, and an increased probability of cytokine storms (37). In a study conducted to investigate clinical symptoms in individuals with diabetes, researchers discovered that the most frequently observed symptoms among these individuals were fever at 89.6%, cough at 77.1%, dyspnea at 68.8%, anorexia at 43.8%, and fatigue at 58.3%. It is noteworthy that the occurrence rates of fever, cough, and fatigue were similarly prevalent in the current study, classifying them as three common symptoms in both research endeavors (38).

Furthermore, in another study involving individuals with diabetes, researchers categorized them into three groups: Euglycemia, secondary hyperglycemia, and diabetic groups. In the first group, fever exhibited the highest prevalence at 86.3%, followed by cough at 56.8%, along with fatigue and shortness of breath. The second group displayed symptom prevalence similar to the first. However, in the third group, fever remained predominant, with an occurrence rate of 85.7%, followed by cough and fatigue at 57.1% in the second position and shortness of breath at 35.7% in the third position. These symptoms were the most frequent within these groups, and it is noteworthy that the present study also reported higher occurrence rates for these symptoms, albeit with varying prevalence percentages. For instance, in the present study, cough had a prevalence rate of 84%; nevertheless, fever and shortness of breath were prevalent at 56%, and fatigue had a rate of 43% (39).

Another study investigated the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in individuals with documented cardiovascular disease. A comprehensive examination was carried out on a total of 184 participants, who were divided into two groups: severe and non-severe cases. In general, shortness of breath emerged as the predominant symptom, affecting 75.54% of the participants, followed by cough at 46.19%, chest pain at 42.39%, and fatigue at 26%. The aforementioned symptoms proved to be prevalent among this group of individuals, and the current study also identified a substantial occurrence rate of these symptoms (40).

Another research study was undertaken to investigate the impact of COVID-19 among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), specifically focusing on this population. This investigation encompassed 1 069 participants who were categorized into two groups: those with COPD and those without. In the COPD group, the most prevalent symptom was shortness of breath at 81.1%, followed by cough at 71.7%, hypoxemia at 43.4%, and fever at 34%. Conversely, in the non-COPD group, cough was the dominant symptom at 70%, followed by fever at 49% and shortness of breath at 26%. A comparison between the aforementioned study and the present study reveals that the occurrence of fever and cough in the current study population surpassed that in both the COPD and non-COPD groups. However, the prevalence of shortness of breath in the current study population was lower than in the COPD group but higher than in the non-COPD group (41).

In another distinct study involving 47 individuals who were co-infected with both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the results unveiled that fever was the most prevalent symptom at 87.23%, followed by cough at 48.93% and shortness of breath at 21.27%. Headaches were less common, with an incidence rate of 6.38%, highlighting a significant deviation from the findings in the present study (42). The aforementioned study centers on the repercussions faced by solid organ transplant recipients in the United States who have contracted COVID-19. The study delves into various aspects, including mortality rates, complications, and specialized treatments designed for this particular patient group. In this study cohort, cough and shortness of breath emerged as the most prevalent symptoms, with occurrence rates of 70%, followed by fever at 61% and fatigue at 37%. When contrasting these statistics with the outcomes of the present study, noticeable disparities between the findings of these two studies become apparent (42).

In a study conducted to explore the association between obesity and the severity of COVID-19 cases at a specific hospital in Shenzhen, China, 383 patients were assessed and categorized into four groups: underweight, normal, overweight, and obese. Regarding clinical symptoms, fever followed by cough exhibited the highest prevalence across all groups. Fever was reported at 63.5%, 68.5%, 66.7%, and 87.8% in these respective groups; nevertheless, cough was documented at 31.3%, 33.5%, 43%, and 56.1%. By comparing the aforementioned findings to the findings of the present study, the current study revealed a lower incidence of fever, with the most significant difference observed in the obesity group and the least difference in the underweight group. Conversely, the present study showed a higher prevalence of cough than all four groups examined in the aforementioned study (43).

Another study delved into hospitalization rates and clinical characteristics observed in confirmed COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital. Among the clinical symptoms, fever/chills had the highest prevalence at 54%, followed by poor feeding and vomiting at 31% and cough at 29.5%, respectively. It is noteworthy that these findings contrast with the results of the present study. For instance, vomiting, which is one of the most common symptoms in the aforementioned study, has the lowest occurrence rate in the current study (44).

A meta-analysis investigated the prevalence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of COVID-19 cases. In terms of clinical symptoms, headaches were the most prevalent at 67%, followed by fever at 55%, cough at 45%, and myalgia at 35%. These prevalence figures are notable when compared to the studies included in the present study. It is worth mentioning that although the occurrence of headaches and fever aligns with the present study, there is a significant contrast in the prevalence of cough, which is notably lower in the findings of the current study (45).

Considering the constraints inherent in the present study, such as the unavailability of COVID-19 infection records, limited cooperation from certain patients, and relatively small sample size from a statistical standpoint, it is advisable to embark on further research endeavors with more extensive and diverse samples. This approach will facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter at hand.

In conclusion, this study examined a diverse sample, revealing prevalent symptoms among individuals with various conditions, including neurological manifestations. The neurological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 is significant, and understanding these symptoms is crucial for comprehensive patient care. However, it is crucial to emphasize that obtaining a more profound understanding of these symptoms necessitates access to the names of the medications prescribed to the patients, a limitation that the present study acknowledges. To enhance our understanding, further research with larger and more diverse samples is recommended, considering the limitations faced in this study, including the data.

5.1. Conclusions

The obtained findings of this study underscore the importance of recognizing the differential impact of the virus on individuals with schizophrenia, BD, migraine, and Alzheimer's disease compared to those without any neurologic disorder. Notably, the prevalence of specific symptoms, such as headaches, exhibited substantial variations across the groups. Cough emerged as the most prevalent symptom among COVID-19-infected individuals across all subgroups, with over 79% of participants reporting this manifestation. Conversely, vomiting exhibited the lowest occurrence, documented in only 14.3% of the cases. This finding emphasizes the necessity for tailored approaches in the clinical management of COVID-19 patients with diverse neurological backgrounds. Understanding these disparities allows for more precise diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the elevated prevalence of certain symptoms in individuals with underlying neurological conditions highlights the heightened vulnerability of these groups to COVID-19 complications. This finding underscores the imperative of prioritizing preventive measures, early intervention, and specialized care for individuals with conditions such as schizophrenia, BD, migraine, and Alzheimer's disease during the ongoing pandemic. Ultimately, a comprehensive understanding of these interactions will not only enhance clinical outcomes but also inform public health strategies aimed at safeguarding vulnerable populations.