1. Background

Pain can have irreversible consequences for patients, and one common type of perceived pain is headaches (1-3). The prevalence of headaches worldwide is very high, with very few individuals not experiencing headaches at some point in their lives. In fact, in terms of the number of affected individuals, headaches are recognized as the most common neurological disorder (4-6).

Headaches come in various types, including tension-type headaches (TTH), migraines, and others. Tension-type headaches is one of the most common types of headaches, which may last from a few minutes to several weeks. In this type of headache, the pain is usually pressing and firm, with mild to moderate intensity, and is typically bilateral (7, 8). Primary headaches are among the most common disorders, with a prevalence of over 90%, and the prevalence of TTH headaches has been reported to be between 24 to 43%. These types of headaches significantly impact various aspects of life and require therapeutic and non-therapeutic interventions (9).

Individuals with headaches consider factors such as emotions, stress, light, season, noise, type of food, and fatigue as headache triggers. It is recommended that patients prevent headache-inducing stimuli. Healthcare providers should educate patients on avoiding migraine-inducing triggers to prevent the onset of headaches (10-13).

Chronic headaches limit daily activities, disrupt family and social relationships, and create economic pressures, affecting various aspects of the patient's life, including their quality of life (14, 15). Headaches lead to the development of psychosocial problems in patients, threatening various aspects of their lives (16-19). In patients with headaches, these complications may be more specific and especially related to symptoms of head pain (20, 21). Suicidal thoughts have a significant prevalence in people with headaches, and the high prevalence of headaches in patients with psychiatric disorders is considered an independent or dependent factor for suicide (22, 23).

In the elderly population, headaches are a common problem and are significant in causing psychological problems, including depression (24, 25). The elderly population is increasing worldwide, and this growth is one of the most important concerns for the healthcare system. It is predicted that by 2025, there will be 1.2 billion elderly individuals in the world, with over two-thirds residing in developing countries. Additionally, it is expected that by 2025, the increase in the elderly population in developing countries will reach approximately 300% (26-28). During old age, factors such as retirement, physical weakness, psychological stress, chronic illnesses, and lack of financial independence can lead to significant psychological pressures. Therefore, identifying diseases in the elderly population can contribute to timely diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately improve their quality of life (28-30).

2. Objectives

This study aims to investigate the prevalence of primary headaches and the factors affecting the acceptance of perceived pain in elderly individuals with headaches.

3. Methods

In this cross-sectional descriptive study, a total of 1560 elderly individuals from the city of Ilam were initially screened, and ultimately, 238 patients met the study's inclusion criteria. The researchers identified eligible elderly individuals by designing specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. The inclusion criteria included having a minimum of 6 months of headache history, confirmation of migraine diagnosis by a specialist physician, absence of other types of pain except for headaches, and the ability to communicate with the interviewers. If, during the study, it was diagnosed that the elderly individual was suffering from another illness that could affect pain, they were excluded from the study.

The elderly individuals who agreed to participate in the study after being informed of its objectives completed the questionnaires. If necessary, the interviewers assisted by conducting interviews to complete the questionnaires.

The tools used included the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire, Headache Disability Inventory (HIT-6), and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). The Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire, developed by Welsh and McCracken, consists of 20 questions scored on a 7-point scale (from 0, indicating "never," to 6, indicating "always"), with possible scores ranging from 0 to 120. Higher scores indicate greater pain acceptance. This tool includes two subscales: Engagement in activities and pain acceptance. The engagement in activities subscale involves tracking daily activities despite pain, while the pain acceptance subscale involves a relative lack of effort to avoid or control pain. Eleven items in this tool are directly related to pain acceptance, while the other nine items in the activities section are scored in reverse (31, 32).

In addition, the study used the HIT-6 tool to assess the severity of migraines and their impact on daily activities. This tool consists of 6 questions with a 6-point Likert Scale, where a score of 5 is assigned for responses indicating "most of the time," and a score of 1 for responses indicating "never." The total score ranges from 6 (minimal pain intensity) to 30 (severe pain) (33, 34). The BPI was used to measure pain, assessing pain status on a scale from 0 (least pain) to 10 (most pain) (35).

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical code (IR.KUMS.REC.1398.280), and all ethical guidelines were followed. The study data were analyzed using SPSS 16 software.

4. Results

Results showed that out of 1260 patients included in the study, 238 elderly people had one of the types of headaches (Tables 1 -4).

| Variables | No. (%) | TTH | MIG | UNC | CH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 126 (52.9) | 46 | 42 | 26 | 12 |

| Female | 112 (47.1) | 39 | 33 | 39 | 1 |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 65 - 70 | 50 (21) | 20 | 24 | 5 | 1 |

| 71 - 75 | 51 (21.4) | 21 | 14 | 12 | 4 |

| 76 - 80 | 76 (31.9) | 24 | 19 | 28 | 5 |

| 81 - 85 | 48 (20.2) | 13 | 15 | 17 | 3 |

| > 85 | 13 (5.5) | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 145 (60.9) | 48 | 44 | 45 | 8 |

| Elementary | 62 (26.1) | 25 | 20 | 14 | 3 |

| Diploma | 27 (11.3) | 9 | 11 | 5 | 2 |

| University | 4 (1.7) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Previous job | |||||

| Housewife | 110 (46.2) | 38 | 37 | 24 | 11 |

| Manual worker | 109 (45.8) | 38 | 31 | 39 | 1 |

| Employee | 15 (6.3) | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Other layers | 4 (1.7) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Addiction | |||||

| Yes | 75 (31.5) | 19 | 27 | 27 | 2 |

| No | 163 (68.5) | 66 | 48 | 38 | 11 |

Abbreviation: TTH, tension-type headaches.

| Variables | Pain Interference | Headache Disability | Chronic Pain Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 5.92 ± 2.27 | 13.16 ± 7.96 | 81.11 ± 30.65 |

| Female | 6.88 ± 2.35 | 16.53 ± 8.8 | 68.23 ± 32.28 |

| P-Value, F | 0.21, 1.56 | 0.003, 8.98 | 0.46, 0.52 |

| Age (y) | |||

| 65 - 70 | 3.36 ± 0.66 | 6.84 ± 1.11 | 111.5 ± 5.96 |

| 71 - 75 | 4.72 ± 0.69 | 7.34 ± 0.64 | 100.35 ± 17.27 |

| 76 - 80 | 7.02 ± 0.86 | 15.30 ± 5.58 | 65.17 ± 18.13 |

| 81-85 | 9.27 ± 0.49 | 25.91 ± 1.44 | 37.10 ± 8.4 |

| > 85 | 9.92 ± 0.27 | 29.46 ± 0.51 | 33.46 ± 4.82 |

| P-Value, F | 0.000, 608.77 | 0.000, 399.08 | 0.000, 256.82 |

| Education | |||

| Illiterate | 6.41 ± 2.32 | 14.74 ± 8.57 | 74.64 ± 31.28 |

| Elementary | 5.8 ± 2.45 | 13.08 ± 8.73 | 83.95 ± 32.89 |

| Diploma | 7.48 ± 1.92 | 18.66 ± 6.75 | 56.29 ± 26.83 |

| University | 6.25 ± 2.06 | 14.5 ± 7.54 | 78.25 ± 30.77 |

| P-Value, F | 0.02, 3.32 | 0.04, 2.75 | 0.002, 4.93 |

| Previous job | |||

| Housewife | 6.40 ± 2.02 | 14.14 ± 8.05 | 75.9 ± 29.35 |

| Manual worker | 6.79 ± 2.32 | 16.16 ± 8.63 | 69.11 ± 32.27 |

| Employee | 4 ± 2.97 | 11.26 ± 9.74 | 100.8 ± 33.57 |

| Other layers | 3 ± 0 | 6 ± 1.63 | 116.75 ± 1.89 |

| P-Value, F | 000, 10.10 | 0.01, 3.53 | 0.000, 7.30 |

| Addiction | |||

| Yes | 6.54 ± 2.32 | 15.41 ± 8.64 | 72.2 ± 31.52 |

| No | 6.29 ± 2.35 | 14.44 ± 8.47 | 76.36 ± 32.25 |

| P-Value, F | 0.44, 0.03 | 0.41, 0.63 | 0.35, 0.58 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain interference | |||||

| Regression | 225138.681 | 1 | 225138.681 | 2969.85 | .000 |

| Residual | 17890.714 | 236 | 75.808 | ||

| Total | 243029.395 | 237 | |||

| Headache disability | |||||

| Regression | 200546.273 | 1 | 200546.273 | 1114.06 | .000 |

| Residual | 42483.122 | 236 | 180.013 | ||

| Total | 243029.395 | 237 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | T | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| Pain interference | 158.747 | 1.63 | - | 97.020 | 0.000 |

| -13.13 | 0.24 | -0.962 | -54.49 | 0.000 | |

| Headache disability | 125.417 | 1.74 | - | 72.01 | 0.000 |

| -3.41 | 0.10 | -0.908 | -33.37 | 0.000 | |

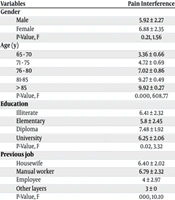

Results showed that the mean ± SD score of Pain Interference was 6.37 ± 2.34, headache disability was 14.75 ± 8.52, and Chronic Pain Acceptance was reported as 75.05 ±32.02 (Tables 2 ,3). Additionally, pain intensity and disability scores were reported to be lower in patients who had higher pain acceptance (Table 4).

5. Discussion

The prevalence of chronic diseases has been high worldwide, affecting various aspects of patients' health (2, 36-38). Pain, in general, imposes a significant burden of short-term and long-term consequences on patients (39-41). In patients with headaches, especially in the elderly, the impact of pain can be more severe and destructive (42, 43).

According to the findings, the mean ± SD of Pain Interference was 5.92 ± 2.27 for men and 6.88 ± 2.35 for women, 6.54 ± 2.32 for people with a history of addiction, and 6.40 ± 2.02 for housewives. Additionally, elderly individuals reported various types of headaches. In the study by Feleppa et al., which included 1237 elderly patients with a mean age of 75.6 years, conducted between 2006 and 2014, 24.4% suffered from headaches. The most common diagnoses were episodic migraine at 3.0%, probable migraine at 13.8%, and 55.6% of migraine patients used medication to reduce migraine pain (44). In the study by de Rijk et al., 13.8% of patients had migraines with aura, 13.0% had both types of migraines, 58.6% experienced unilateral pain, 50.2% reported throbbing-type pain, and 79.5% reported both phonophobia and photophobia (45). In the study by Camarda and Monastero, out of 1031 elderly individuals, 225 (21.8%) reported recurrent headaches, 1.3% reported OH, 4.6% reported MH, and 16% reported TTH (46). In the study by Tai et al., which divided patients into two groups, those under 55 years and those over 55 years, 165 patients were examined, with 95 individuals in the under 55 group and 70 in the over 55 group. Tension-type headaches were reported as the most common condition in the elderly group at 45.7%, while migraine without aura was reported at 54.7% in the younger group (47). Additionally, in the study by Zhang et al., the one-year prevalence of primary headaches was reported as 10.3%, TTH as 2.02%, migraines as 0.85%, chronic headaches as 3.79%, and unclassified headaches as 3.63% (48).

According to the findings, patients diagnosed with migraines before the age of 18 had higher symptom severity and frequency compared to those diagnosed later, which is consistent with the results of the study by de Rijk et al (45).

5.1. Conclusions

Considering that pain and disability were reported to be lower in patients with higher pain acceptance scores, therapeutic and psychological interventions aimed at increasing pain acceptance are recommended.

.png)