1. Background

Spine surgery can be performed under either general anesthesia (GA) or regional anesthesia (RA), specifically epidural anesthesia administered via catheter infusion (1). The RA offers several benefits, including fewer pulmonary complications (2), less blood loss (3), reduced hypoxic episodes and thrombotic events (4), and a lower incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. A recent review highlighted RA's superiority in multiple studies, noting decreased postoperative pain (1). However, GA has its drawbacks, as high opioid doses can lead to nausea, vomiting, and temporary hypotension, while local anesthesia-induced motor weakness may cause difficulties after surgery (5).

Some studies have reported lower postoperative morbidity and mortality with RA, though conclusive evidence is lacking (6). Additionally, a retrospective study of 473 patients who underwent spinal anesthesia demonstrated RA's cost-effectiveness due to significantly reduced anesthesia time (7).

The RA offers another advantage for spinal operations performed in the prone position: Patients remain awake and can adjust their position, potentially preventing brachial plexus nerve injury and facial pressure necrosis (8).

While various studies have examined the relationship between RA and outcomes such as cost-effectiveness and surgical complications, conflicting conclusions have been reported, preventing a definitive consensus (6).

2. Objectives

Against this background, this prospective randomized study was designed to compare two groups of patients requiring spinal neurosurgery under RA versus GA.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This randomized clinical trial with a parallel group design was conducted on patients undergoing spine surgery between August 23, 2021, and August 23, 2022, at Imam Hossein Hospital, Tehran, and the first patient was enrolled in the study on August 28, 2021. The study protocol was registered at the (Iranian Clinical Trials Registration Center), which operates under World Health Organization supervision. The protocol received the clinical trial ID number IRCT20210722051955N1 on August 7, 2021.

3.2. Ethical Consideration

The Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences reviewed and approved this study (registration ID: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1399.716) on February 16, 2021. The researchers adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki throughout the trial.

3.3. Randomization

While the study was not blinded, randomization was performed using a random number table. Participants were divided into two groups based on their entry number and the randomized table.

3.4. Eligibility

Inclusion criteria were: Patients aged 18 to 70 years; those with spinal discopathy requiring surgery on the lumbar, thoracic, cervical, or whole spine; first-time surgical patients; and individuals of both sexes. Exclusion criteria were: Patients who did not provide written consent; those with known kidney, liver, or pulmonary failure; coagulopathy; contraindications for RA; and patients with pedicle screw indications.

3.5. Sample Size

Based on a 2003 study by Demirel et al. in the Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology, the average duration for GA patients was 137.60 ± 26.80 minutes, and for RA patients was 118.80 ± 35.42 minutes (8). The calculated effect size was 0.598. Using an independent t-test to compare average results, with an alpha error of 0.05 and 80% power in a two-arm study, the required sample size was 72. Accounting for a 20% withdrawal rate, the final sample size was set at 100.

3.6. Intervention

Standard monitoring (blood pressure, electrocardiography, and peripheral oxygen saturation) was established along with intravascular access. Regional spinal anesthesia was administered via epidural injection of pethidine 1 mg/kg (Aburaihan Pharmaceutical Company, Tehran, Iran) and intravenous injection of dexmedetomidine 0.2 μg/kg (Exir Pharmaceutical Company, Borujerd, Iran). Patients were then placed in a prone position. Oxygen was provided via nasal cannula at 2 L/min. Mild sedation was achieved using a propofol and midazolam 0.05 mg/kg infusion. Sedation depth was monitored using the modified observer’s assessment of alertness/Sedation Scale (OAAS).

For GA, induction was performed with propofol (Pofol®) 2 mg/kg, fentanyl 3 μg/kg (Caspian Co), and midazolam 0.05 mg/kg. Maintenance was achieved with fentanyl 1 μg/h and isoflurane 1 μg/min (Baxter Co). Atracurium provided neuromuscular relaxation with an induction dose of 0.5 mg/kg and subsequent doses of 0.125 mg/kg as needed. Inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) ranged from 30% to 50%, with end-expiratory CO2 levels set between 35 and 45 mmHg. Patients were placed in a prone position post-surgery once hemodynamically stable. Cardiovascular issues were managed with vasopressors and/or volume as determined by the anesthesiologist.

Surgical time was measured from incision to dressing application. Postoperative complications, including spinal headache, bleeding, nausea, vomiting, and the need for antiemetic medication, were assessed in both groups.

3.7. Outcome Measurement

The primary outcome of this study was operation duration. Secondary outcomes included the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), patients' acetaminophen requirements (g), blood loss, vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure), postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) incidence and subsequent need for pharmacotherapy, anesthesia duration, and patient satisfaction. The study also examined cost-effectiveness and patient satisfaction.

3.7.1. Operation Duration

Operation duration comprised three components: Pre-surgical time (from patient admission to the operating room until surgery start), surgical time (from first incision to last suture), and total time in the operating room (8).

3.7.2. Oswestry Disability Index

The ODI, also known as the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, assesses patients' permanent functional disability. It consists of 10 patient-answered questions, each scored out of 5, with a total score calculated (9, 10). Several studies support the use of the ODI for tracking changes in disability over short-term intervals. For example, Koivunen et al. reported that ODI scores were responsive in patients undergoing lumbar spinal surgery, thereby effectively capturing the changes in functional status during the postoperative recovery phase (11). Similarly, Lee et al. demonstrated that the ODI possesses adequate psychometric properties to detect changes in disability levels over time, even though its original design was for chronic conditions (12). These studies provide evidence that the ODI can be applied as a tool for evaluating transient disability when the focus is on monitoring functional improvement or deterioration within a limited timeframe.

3.7.3. Blood Loss

Blood loss, a major surgical complication that can increase mortality by up to 20% in severe cases, was measured using two methods. First, blood collected during surgery was measured directly in milliliters using a graduated cylinder. Second, hemoglobin (Hgb) levels (mg/dL) were measured before and immediately after surgery, with the decrease reported (13).

3.7.4. Acetaminophen Dose

Post-surgery, patients remained hospitalized in the neurosurgery department until stable. Acetaminophen was administered intravenously or orally as needed, up to the maximum daily dose (2 g for elderly patients, 4 g for non-elderly patients). The total acetaminophen received during hospitalization was recorded in grams (14).

3.7.5. Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale: (1) Very bad; (2) bad; (3) moderate; (4) good; and (5) very good (15).

3.7.6. Surgeon Satisfaction

Surgeon satisfaction was evaluated using a 3-point Likert scale: (1) Bad; (2) moderate; and (3) good (15).

3.7.7. Vital Signs

Heart rate (beats per minute), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) were measured at three time points: Immediately before anesthesia in the supine position and after complete anesthesia induction, before surgery in both supine and prone positions (16, 17).

3.7.8. Additional Outcomes

The study also measured anesthesia duration for each group (minutes), muscle relaxation, headache episodes, nausea and vomiting episodes, and medication requirements for nausea and vomiting control during hospitalization (18).

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using unpaired t-tests and Mann-Whitney tests. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (95% confidence interval). Results are presented as means and standard deviations. IBM SPSS version 25 was used for statistical analysis. F-tests were employed to compare heart rate and blood pressure across three different groups (19-21).

4. Results

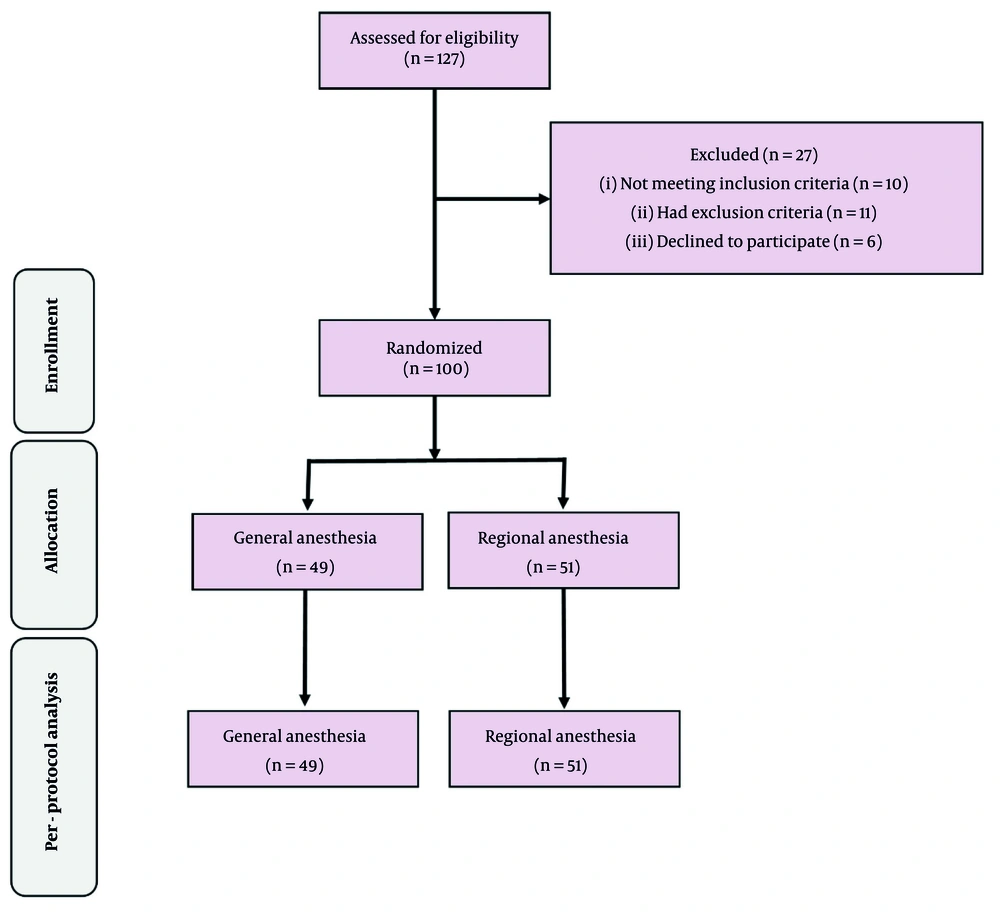

Figure 1 illustrates the trial's progression following the consolidated standards for reporting trials (CONSORT) guidelines. Table 1 presents the patients' characteristics. Statistical analyses revealed no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender distribution, or surgery type. One patient in the RA group experienced a failed procedure.

| Parameter | RA (n = 51) | GA (n = 49) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 41.5 ± 9.5 | 40.4 ± 10.4 | 0.664 |

| Gender (female/male) | 22/29 | 22/28 | 0.932 |

| Hgb pre-operation (mg/dL) | 14.3 ± 1.7 | 14.3 ± 1.6 | 0.651 |

| ODI pre-operation | 34.3 ± 9.2 | 35.5 ± 8.4 | 0.393 |

| Type of Surgery | 0.172 | ||

| One-side fenestration | 19 (37.3) | 10 (20.4) | |

| Interlaminar discectomy or both-side fenestration | 23 (45.1) | 29 (59.2) | |

| Laminectomy or fenestration on 2 level | 9 (17.6) | 10 (20.4) |

Abbreviations: Hgb, hemoglobin; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; GA, general anesthesia; RA, regional anesthesia.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Laminectomy or fenestration on 2 levels: This category refers to patients who underwent surgical decompression at two contiguous spinal levels. The procedure performed — either laminectomy (removal of the lamina) or fenestration (creating a surgical window for decompression) — was determined intraoperatively based on the patient’s pathology.

Anesthesia and operation durations were significantly longer in the GA group compared to the RA group (148.3 ± 43.8 vs 121 ± 30.6 minutes and 104.1 ± 43.7 vs 80.8 ± 27.9 minutes, respectively; P < 0.005). The calculated effect size based on primary outcome results was 0.635, with a power of 80.7%. Preoperative ODI scores showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.395).

Total bleeding during hospitalization, calculated by combining intraoperative blood loss and postoperative drainage, is presented in Table 2. Patients under RA experienced more overall bleeding (P < 0.005). Both groups showed a significant reduction in blood Hgb levels after surgery compared to preoperative values.

| Outcome | RA (n = 51) | GA (n = 49) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia duration (min) | 121.0 ± 30.6 | 148.3 ± 43.8 | < 0.001 b |

| Operation duration (min) | 80.8 ± 27.9 | 104.1 ± 43.7 | 0.002 b |

| ODI post-operation | 20.54 ± 5.75 | 28.53 ± 5.46 | 0.078 |

| Bleeding (mL) | 268.4 ± 302.0 | 236.1 ± 150.0 | 0.553 |

| Hgb post operation (mg/dL) | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 12.4 ± 1.6 | 0.67 |

| Muscle relaxation | 0.002 b | ||

| Bad | 13 (25.5) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Moderate | 13 (25.5) | 8 (16.3) | |

| Good | 25 (49.0) | 39 (79.6) | |

| Acetaminophen dose (g) | 3.9 ± 2.1 | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 0.011 b |

| Nausea | 21 (41.1) | 2 (4.1) | < 0.001 b |

| Vomiting | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.043 b |

| N/V pharmacotherapy | 21 (41.1) | 2 (4.1) | < 0.001 b |

| Headache | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0.57 |

| Patient satisfaction | 0.020 b | ||

| Very bad | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bad | 0 (0.0) | 7 (14.3) | |

| Moderate | 19 (37.3) | 15 (30.6) | |

| Good | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Very good | 32 (62.7) | 25 (51.0) | |

| Surgeon satisfaction | 0.002 b | ||

| Bad | 5 (9.8) | 9 (18.4) | |

| Moderate | 14 (27.5) | 26 (53.1) | |

| Very good | 32 (62.7) | 14 (28.5) | |

| HR (position) | |||

| Before anesthesia (supine) | 86.65 ± 13.82 | 88.95 ± 13.15 | 0.489 |

| After anesthesia (prone) | 84.41 ± 12.42 | 87.69 ± 13.65 | 0.965 |

| After anesthesia (supine) | 79.18 ± 12.43 | 82.12 ± 15.28 | 0.181 |

| SBP (position) | |||

| Before anesthesia (supine) | 130.76 ± 14.72 | 134.19 ± 18.73 | 0.110 |

| After anesthesia (prone) | 118.73 ± 18.92 | 121.02 ± 15.29 | 0.223 |

| After anesthesia (supine) | 114.12 ± 16.72 | 113.67 ± 14.79 | 0.829 |

| DBP (position) | |||

| Before anesthesia (supine) | 82.53 ± 11.06 | 82.53 ± 13.65 | 0.721 |

| After anesthesia (prone) | 73.22 ± 15.57 | 76.65 ± 11.60 | 0.213 |

| After anesthesia (supine) | 70.84 ± 13.87 | 73.00 ± 14.70 | 0.493 |

Abbreviations: ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; Hgb, hemoglobin; N/V, nausea/vomiting; HR, heart rate (pulse/min); SBP, systolic blood pressure (mmHg); DBP, diastolic blood pressure (mmHg); GA, general anesthesia; RA, regional anesthesia.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Significant difference.

As anticipated, muscle relaxation during the procedure was significantly greater in the GA group. However, the RA group exhibited a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting, requiring more frequent pharmacotherapy interventions to manage these complications.

While hemodynamic parameters differed within each group, analysis of differences between the GA and RA groups did not yield statistically significant results, as shown in Table 2.

Intragroup analyses of vital signs are presented in Table 3. These analyses were conducted in two ways:

1. Comparing blood pressure changes before and after anesthesia induction in the supine position.

2. Comparing blood pressure changes after anesthesia induction between supine and prone positions.

| Group | Before Anesthesia Supine | Within Group Significance | After Anesthesia Supine | After Anesthesia Prone | Within Group Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA (n = 51) | |||||

| HR | 86.65 ± 13.82 | 0.002 b | 79.18 ± 12.43 | 84.41 ± 12.42 | 0.017 b |

| SBP | 130.76 ± 14.72 | 0.001 b | 114.12 ± 16.72 | 118.73 ± 18.92 | 0.076 |

| DBP | 82.53 ± 11.06 | 0.001 b | 70.84 ± 13.87 | 73.22 ± 15.57 | 0.331 |

| GA (n = 49) | |||||

| HR | 88.95 ± 13.15 | 0.031 b | 82.12 ± 15.28 | 87.69 ± 13.65 | 0.058 |

| SBP | 134.19 ± 18.73 | 0.001 b | 113.67 ± 14.79 | 121.02 ± 15.29 | 0.030 b |

| DBP | 82.53 ± 13.65 | 0.001 b | 73.00 ± 14.70 | 76.65 ± 11.60 | 0.219 |

Abbreviations: HR, heart rate (pulse/min); SBP, systolic blood pressure (mmHg); DBP, diastolic blood pressure (mmHg); GA, general anesthesia; RA, regional anesthesia.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Significant difference.

5. Discussion

This study compared RA and GA in degenerative spine surgeries. The GA group showed better pain control, with lower Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores and reduced analgesic consumption. However, the RA group had shorter hospitalization and operation durations. Interestingly, the RA group experienced higher bleeding volumes, though the number of patients requiring blood transfusions and pre- and postoperative Hgb levels were similar between groups.

Patient satisfaction was higher in the RA group, as was surgeon satisfaction. Postoperative ODI scores showed no significant difference between groups. The RA group reported lower rates of PONV compared to the GA group.

While numerous studies have compared GA and RA in spine surgery, most focused on non-fusion procedures (22). Common primary outcomes included postoperative pain, patient and surgeon satisfaction, surgery and hospitalization duration, bleeding rates, and cost. Our findings align with some previous studies but differ in others.

Regarding hemodynamic stability, unlike previous studies that found worse outcomes in GA groups, our study showed no significant difference between the two groups.

Most studies report higher bleeding rates with GA (8, 22-25)), though two studies showed slightly higher, but not significant, bleeding in RA (7, 26). This study found significantly higher bleeding in the RA group. This could be due to increased venous pressure from the Valsalva maneuver, as patients are awake and prone during RA procedures, potentially leading to more bleeding from epidural vessels. Although RA is predominantly associated with reduced intraoperative blood loss, our findings indicate a higher blood loss in the RA group. One potential explanation is the variation in venous hemodynamics observed under RA. Patients under RA maintain spontaneous ventilation and may experience incomplete sympathetic blockade, leading to fluctuations and transient increases in venous pressure. These hemodynamic changes, possibly exacerbated by surgical positioning and patient-specific factors, could result in increased bleeding from venous channels. Similar observations have been noted in the literature, suggesting that under particular clinical conditions, RA might contribute to a higher overall blood loss than expected (27, 28).

Despite higher intraoperative bleeding in the RA group, postoperative Hgb decreases were similar between groups. This may be attributed to lower systemic blood pressure during GA, resulting in less expected blood loss. The similar Hgb decrease in both groups, despite higher bleeding in RA, could be related to propofol's hemolytic effect (29). Consequently, the overall postoperative Hgb reduction was comparable in both groups, regardless of the higher bleeding observed in the RA group.

This study demonstrates that pain levels (VAS) and analgesic consumption were higher in the GA group compared to the RA group, aligning with most research in this field (5, 7, 22-25). Consistent with other studies, the RA method resulted in less postoperative pain and a reduced need for pain relief.

Muscle relaxation was more effective in the GA group than in the RA group, likely due to GA's impact on muscle tone. For patients undergoing RA, using an appropriate muscle relaxant during surgery is advisable, as it can simplify pain management postoperatively (30). Although GA inherently provides better muscle relaxation through the use of neuromuscular blocking agents, patients receiving RA may not achieve equivalent levels of muscle relaxation. This difference can have implications for postoperative recovery. Inadequate muscle relaxation during surgery may lead to increased postoperative muscle stiffness and pain, which could hinder early mobilization and prolong recovery. Recognizing this, future protocols in patients receiving RA might benefit from the incorporation of targeted muscle relaxation strategies, such as supplemental local infiltration or additional regional nerve blocks. These interventions may improve intraoperative conditions and subsequently promote enhanced postoperative recovery by reducing muscle tension and pain (31, 32).

A systematic review examined eleven studies comparing GA and RA for spinal lumbar surgery, including four RCTs, three case-control trials, two retrospective analyses, and two prospective cohorts. Seven studies found lower heart rates and mean arterial pressures in the RA group, while seven reported reduced postoperative analgesic requirements and/or lower pain scores in the RA group (1).

The operating room is a critical and expensive hospital resource, with a high percentage of patients admitted for surgical procedures. Managing the operating theater is complex, involving scheduling surgeries efficiently to maximize profits without increasing costs or patient wait times (33). Reducing operation duration significantly aids in operating room management and helps decrease the workload of medical staff and surgeon fatigue (34, 35). This study found that spine surgery using RA took considerably less time than GA. Additionally, the duration of anesthesia was significantly shorter in the RA group. These findings suggest that RA can positively impact operating room management, staff workload, and surgeon fatigue.

A 2020 meta-analysis of 1747 patients undergoing retrograde intrarenal surgery showed that RA patients had shorter operation times compared to GA patients, but similar VAS scores and hospital stays (36).

This study finds that GA patients experience longer anesthesia duration and hospital stays than RA patients, consistent with similar research (22, 25). Most studies comparing anesthesia duration between the two methods show longer times for GA, except for one randomized and one non-randomized clinical trial that found no significant difference (23, 24). The extended time for GA can be attributed to induction and recovery periods. In this study, GA patients had longer hospital stays and higher costs, supporting findings from comparable studies (22, 25).

Postoperative nausea and vomiting, a common complication after spine surgery, occurred more frequently in the RA group in this study. This contrasts with most studies, where GA patients typically experience more nausea and vomiting (23, 37). Some studies align with the present findings, potentially due to variations in drugs used for GA and RA across studies (26). The difference may be explained by the anti-nausea effects of GA (38). For patients undergoing spinal surgeries with RA, prescribing anti-nausea medication based on individual needs may be beneficial.

Patient satisfaction, which reflects perceived care outcomes, influences treatment choices (39). This study found significantly higher patient and surgeon satisfaction with RA compared to GA. As shown in Table 2, few studies have examined satisfaction levels. Vural and Yorukoglu reported significantly higher patient satisfaction with RA. Surgeon preferences for anesthesia methods vary, with some favoring RA and others preferring GA (7, 24, 40).

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 RCTs involving 733 patients found higher rates of hemodynamic disorders in the GA group. The RA group showed lower rates of nausea and vomiting, shorter hospital stays, and reduced analgesic needs. These findings align with a 2017 meta-analysis and largely correspond with the current study and the data presented in Table 2 (41, 42).

5.1. Limitations

This study was conducted in a single tertiary hospital with high patient turnover. To enhance the generalizability of the findings, a multicenter study with a larger sample size is recommended. Additionally, the surgeon's awareness of the anesthesia type may have introduced bias regarding surgery duration. Another limitation of our study is that postoperative narcotic and muscle relaxant requirements were not recorded, which may limit the comprehensive evaluation of overall analgesic management protocols.

5.2. Conclusions

Over recent decades, numerous clinical studies have compared regional and GA. This study contributes to addressing some of the ongoing questions in this field. In line with most previous research, our findings suggest that RA is a viable alternative to GA for spine surgery. The results largely corroborate those of similar studies in this area.