1. Introduction

HIV-1 is a retrovirus causing profound CD4 depletion, probably because of initial massive decrease of gut-associated memory T cells, and then chronic immune activation, resulting in decreasing of homoeostatic T-cell responses and progressive immunodeficiency. CD4 receptor is the cardinal target for HIV-1; however, specific chemokine receptors are important secondary cellular receptors (1, 2). Seroconversion in HIV infection presents with many clinical manifestations, which may take 10 years or more to result in AIDS and finally death (3). HIV infection should be considered in some particular clinical syndromes, laboratory abnormalities and undesired responses to therapeutic interventions (Table 1) (4). HIV effects on the brain can be evident at any level of immune function, but may become more obvious with disease progression. Minor cognitive deficits are quite common and without treatment, a significant part of patients with HIV infection would develop a clinical brain disorder. In the early stage, it may manifest as a syndrome almost indistinguishable from mania, but a progressive, subcortical dementia commonly evolves. The situation is characterized particularly by infinite slowness of movement and mentation, which are severely disabling. Space-occupying lesions of the brain are prevalent in advanced HIV infection phase. Most probable diagnoses are primary lymphoma of the brain and abscess resulting from reactivation of toxoplasmosis (4). HIV may affect the nervous system directly, producing distinct neurological syndromes, or indirectly, by causing immunodeficiency with a resultant susceptibility to opportunistic infections like toxoplasma gondii. Nervous system infection with HIV-1 can produce extent clinical disorders such as sensory neuropathies, myelopathy and dementia. These disorders do not ordinarily appear till advanced stages of HIV infection and other AIDS defining illnesses or immunosuppression occur before these neurological syndromes (5).

| Aseptic meningitis with severe systemic symptoms |

|---|

| Atypical mononucleosis syndrome (not EBV- or CMV-related) |

| Cerebral space-occupying lesions |

| Chronic vaginal thrush |

| Difficult to manage psoriasis, dermatoses |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma |

| Oral candidiasis (especially in the absence of antibiotic use) |

| Persistent lymphadenopathy and symptoms of immune activation |

| Tuberculosis |

| Laboratory abnormalities where HIV should be considered |

| Unexplained anergy |

| Hypergammaglobulinemia, new or unexplained |

| Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, lymphopenia without cause |

| Pneumonia unresponsive to standard therapy |

| Recurrent antibiotic-associated rash |

a Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein-Barr Virus; CMV; Cyto Megalo Virus.

2. Case Presentation

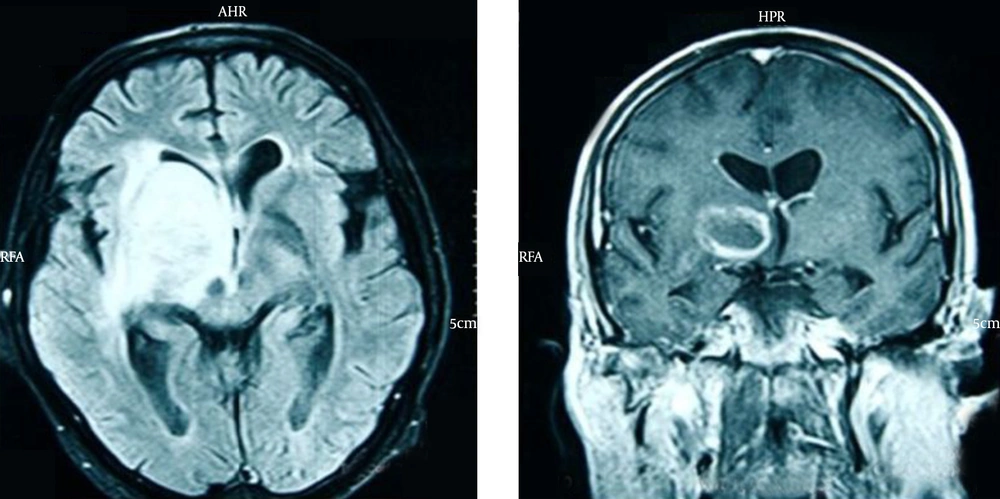

The patient was a 47-year-old man admitted to our emergency department with fever and confusion progressing for two days. His complaints began 20 days before with acute onset left-side hemiplegia and right-side ptosis; he was candidate for biopsy due to imaging findings consistent with a brain mass. He had a positive history of treated lung tuberculosis four years ago with multiple calcified fibrotic bands and calcified nodule in some parts of the right side of lungs on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (Figure 1); also, a history of dysphagia four months before, which esophageal endoscopic examination revealed diffuse mucosal candidiasis. He was a heavy vehicle driver far from his family in last two years. He denied any intravenous drug abuse; he was an opium inhalation addict which he quitted 9 years before and a 30-pack year smoker. At admission in emergency department, he had an auxiliary temperature of 39.5 ºC, 36/min respiratory rate, 114/min pulse rate and blood pressure of 140/80mmHg. He had a tattoo on his left arm, diffuse rhonchi in both lung sides and a midsize non-reactive right pupil, but normal size reactive left one. In laboratory examination, he had lymphopenia with absolute lymphocyte count of 370. Due to these findings and medical histories, rapid HIV antibody test was requested, which revealed a positive result. Then we performed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intravenous contrast showing a ring enhancement lesion in the right basal ganglia suggesting of brain toxoplasmosis (Figure 2). Therefore, treatment with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, folic acid and dexamethasone began and serologic tests for toxoplasmosis requested. Anti-toxoplasmosis IgG had positive results. Unfortunately, despite treatment the patient died due to multiorgan failure after one week.

3. Discussion

3.1. Background

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan with worldwide distribution and is one of the most common causes of chronic infection in humans. Activation of cell-mediated immunity after acute infection with T. gondii leads to control but not eradication (6, 7). Toxoplasmosis accompanied with HIV infection is usually caused by reactivation of a chronic infection and appears primarily as toxoplasmic encephalitis presenting as focal brain lesions (7). Characteristically, toxoplasmic encephalitis presents in a subacute manner with focal neurologic deficits such as speech disturbances, motor weakness, fever, headache and altered mental status. Patients can also present with neuropsychiatric manifestations, cranial nerve abnormalities, sensory disturbances, movement disorders, visual field defects, cerebellar dysfunction, meningioma’s and seizures (8, 9). In scarce cases, toxoplasmic encephalitis manifests as a rapidly fatal form (10). Among patients with HIV infection, seroprevalence of antibodies to T. gondii mirrors rates of seropositivity in the general population. Patients older than 50 years were more likely to have antibodies against T. gondii (11, 12). Without receiving effective prophylaxis, patients with AIDS and < 100 CD4 cells/mm3, had a higher chance for developing reactivated toxoplasmosis, which commonly involves the central nervous system (CNS). Appropriate prophylaxis can effectively decrease this rate (13-15).

3.2. Diagnosis

Toxoplasma abscesses respond to appropriate antibiotic therapy, so early diagnosis is important (4). T. gondii infection is diagnosed by serologic studies. Anti-T gondii IgG and c are the most commonly used. Although IgM could be eliminated a few weeks after the infection, it may be detected even after one year. Therefore, presence of IgM antibodies does not necessarily mean a recent infection. IgG titers peak within 1-2 months after infection but remain elevated for the whole life. Between 97% and 100% of HIV-infected patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis have anti-T gondii IgG antibodies. Therefore, the absence of antibodies against T. gondii makes the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis unlikely (8, 16, 17). Brain imaging is essential for diagnosis and management of patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis. Computed tomography (CT) scan reveals bilateral, multiple, hypodense, contrast-enhancing focal brain lesions in 70-80% of patients and less frequently present with a single lesion or with no one. These lesions are more commonly seen in the basal ganglia and hemispheric corticomedullary junction. Contrast enhancement often creates a ring-like pattern surrounding the lesion (18, 19). Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than CT scan and thus the preferred imaging technique, especially in patients without focal neurologic abnormalities and those with only one lesion or no lesions on CT scan (20, 21). Although toxoplasmic encephalitis can rarely present with a single mass lesion on MRI, considering an alternative diagnosis like primarily CNS lymphoma should be kept in mind (22). Toxoplasmic encephalitis does not have any pathognomonic finding on MRI and CT scans and distinguishing from primary CNS lymphoma based on neuroradiologic criteria is impossible. Despite all, subependymal location and hyperattenuation on nonenhanced CT scans may suggest the possibility of lymphoma (23). Newer imaging techniques like Fluoride 18 [18F]-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and Thallium 201 single-photon emission computed tomography ([201Tl]-SPECT) have been used to distinguish toxoplasmic encephalitis from primarily CNS lymphoma with single mass lesion (24-27). Empirical treatment of focal brain lesions in patients with AIDS for toxoplasmosis as the most common cause may decrease the rate of unnecessary brain biopsies. Promoted therapeutic options constituted empiric evidence of toxoplasmosis and brain biopsy was reserved for those who did not improve clinically (28-30). Patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis typically experience rapid clinical and even radiologic improvement after initiation of appropriate therapy. Neurologic response after three days is noted in 51% of cases, and in 91% by day 14. Consequently, brain biopsy should be reserved for those without clinical improvement by 10-14 days after the initiation of therapy, or when there is deterioration by the third day (31). Most patients would experience radiologic improvement by the third week, so imaging should be repeated 2-4 weeks later (19).

3.3. Treatment

Treatment of AIDS-associated toxoplasmic encephalitis includes two phases of acute and maintenance. Acute therapy should be considered for six weeks and even more in patients with severe illness without proper response. Thereafter, maintenance therapy is considered to prevent relapse. Improvement in immune function achieved by antiretroviral agents supports their prompt initiation in patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis (13). Corticosteroids can be administered for patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis with cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension. Duration of corticosteroid administration should be as short as possible (preferably no more than two weeks). The outcome of empiric regimens including steroids should be interpreted with caution; improvement may be caused exclusively by reduction of inflammation or by the response of CNS lymphoma to corticosteroid treatment (32).

3.4. Prophylaxis

Primary prophylaxis should be strongly considered in T gondii-seropositive patients with CD4 T-cell counts < 100/µL regardless of clinical status, and in patients with CD4 T-cell counts < 200/µL if an opportunistic infection or malignancy develops. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pyrimethamine-dapsone and pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine are effective agents for this goal (33, 34). T gondii-seronegative, HIV-infected patients should be instructed about measures to prevent acquisition of T gondii infection. These individuals should eat only well cooked meat (internal temperature of 116°C, or no longer pink inside) and wash their hands after touching undercooked meat. Fruits and vegetables should be washed prior to consumption. Patients should avoid contact with materials contaminated with cat feces; handling cat litter boxes should be avoided, and gloves should be worn during gardening. Cat feces should be disposed of daily to avoid maturation of oocysts, and litter box can be cleaned by exposure to boiling water for five minutes.