1. Context

Geoepidemiological studies of autoimmune illnesses such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS) may represent the influence of these infirmities across different areas and racial inhabitants. The epidemiology of MS has been altered in current decades in Iran and other Middle East regions to include the majority of Western Asia and Egypt but excluding the Caucasia (1-3). Prevalence studies offer applicable epidemiological information for a balanced approach to scheduling health care demand. Differences in genes, environment, and their interaction could be attributed to irregularly link to the prevalence of MS (4-6). According to previous publications associated with reported prevalences (n per 100,000) for three regions is recognized as follows:1) high-risk area n > 30; 2) intermediate-risk area n = 5–25; and 3) low-risk area n < 5 (7). However, up to now, MS origin, prevalence, and geographical allocation are not blatant. The reported period of prevalence in Isfahan/Iran showed a remarkable rise in the prevalence of MS (8-16). Studies in Arab countries have also demonstrated that MS prevalence is on the rise. The pattern of disease in Qatar seems to be different from other Middle East countries from its milder clinical and aggressive radiologic disease presentations (2, 12). Therefore, a review related to a comparison of the epidemiology of MS in Iran and other countries in the Middle East is of interest and was investigated.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Survey Method

Population-based studies related to the prevalence of MS in Iran and other countries located in the Middle East were used. The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Google Scholar, Information Science and Technology Abstracts (LISTA, EBSCO publishing), Web of Science, United States National Library of Medicine (PubMed, NLM), and National Institutes of Health with keywords relevant to the “prevalence of multiple sclerosis” were searched. A manual investigation of the reference records from principal editorial and pertinent analysis was also performed.

2.2. Addition and Omission Norms

The subsequent criterion were used to choose documents for inclusion in this review as follows: 1) data related to different cities in Iran; 2) data of prevalence related to the countries in the Middle East such as: Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen; and 3) articles that were found in a single center or did not engage a system of hospitals allocated to well-distinct general residents were disqualified. Figure 1 demonstrates a summation of outcomes recognized in this assessment.

2.3. Drawing out the Information and Appraising Study Eminence

The records drawn-out were based on the studies to date i.e. June 2014. The total number of articles found related to search terms and the selected articles (for each country) between years x–y were selected. The subsequent information was extracted into Table 1 and included study place, reported prevalence, and the number of references. The data that were incorporated are in line with the period and population studied. Each study was appraised based on the category of study design, explanation of population, and the adequacy of the case descriptions. Finally, the reported prevalence of MS in Iran and other Middle East countries includes the total number of references found for each country in addition to the date of published (Table 1).

| Middle East, Reported Prevalence | Year | n/100,000 | Total No. of References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iran | A total of 103 articles; 13 were selected from 2013–2003 | ||

| Tehran | 2010 | 51.9 | |

| Qom | 2013 | 50.4 | |

| All Iranian | 2013 | 5.3–70.4 | |

| Isfahan | 2010 | 93.06 | |

| Cyprus | A total of 7 articles; 2 were selected from 1997–1991 | ||

| The overall MS in four areas studied in Greek-speaking Cyprus | 1997 | 42 | |

| Village, Liopetri | 1991 | 240 | |

| Egypt | A total of 5 articles; 2 were selected from 2013 | ||

| Al Quseir | 2013 | 4.6% (out of 1531 subjects) | |

| Jordan | 1995 | 20 | A total of 13 articles; 3 were selected from 2013–1995 |

| Kuwait | 2013 | 85.05 | A total of 14 articles; 5 were selected from 2013–1986 |

| 2000 | 14.77 | ||

| 1993 | 6.68 | ||

| Qatar | 2010 | 64.57 | A total of 3 articles; 2 were selected from 2013 |

| Saudi Arabia | A total of 7 articles; 5 were selected from 2013–1988 | ||

| A report regarding to the Persian Gulf Region exists that confirm | 2013 | 31–55 | |

| The reported hospital | 1998 | 25 | |

| Turkey | A total of 62 articles; 2 were selected from 2011–1960 | ||

| Kandira | 2011 | 31 | |

| Geyve | 41 | ||

| Erbaa | 53 | ||

| Total | 51 | ||

| United Arab Emirates | |||

| according to the reported article related to years 2000-2007 | 2011 | 54.77 | A total of 2 articles; 1 was selected from 2011 |

| Syria | A total of 2 articles; 2 were selected from 2013–2009. Data not available | ||

| Iraq | A total of 11 articles; 6 were selected from 2013–1958. Data not available | ||

| Yemen, Palestine | Not found. Data not available | ||

| Lebanon | A total of 9 articles; 1 was selected from 2008. Data not available; however, the estimated number ranged from 1200–1700 patients | ||

| Oman | A total of 3 articles; 2 were selected from 2009–2005. Data not Available; however, from a total of 30 patients in 2005 estimated 4. |

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Iran

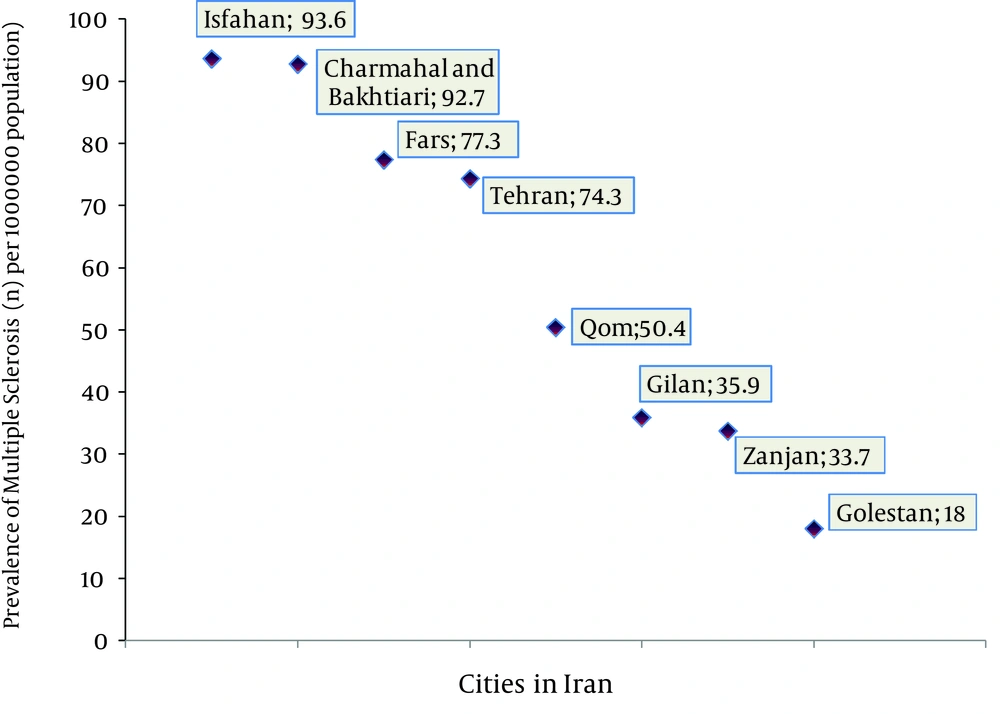

Figure 1 shows the reported prevalence (8) expressed as n per 100,000 for different regions of Iran that can be ranked from the highest to lowest as follows: Isfahan (n = 93.06), Charmahal and Bakhtiari (n = 92.7), Fars (n = 77.3), Tehran (n = 74.3), Markazi (n = 73.8), Hamadan (n = 62.6), Qom (n = 50.4), Azerbaijan (n = 45.5), Kermanshah (n=43.7), Gilan (n = 35.9), Zanjan (n = 33.27), and Golestan (n = 18.0) (8). In another study performed on 901 patients with MS in Isfahan, Iran showed that the mean age of patients was 34.6 years with an age range of 8–87 years (15). An additional study in the same region related to 3,522 patients showed that 2,716 were female and 806 were male and confirmed a prevalence figure of 73.3 and an incidence of 9.1 per 100,000 (11). A recent review of592 patients with MS in Qom, Iran described the mean age of disease onset was 34.25 ± 9.01, in which 11.2% had a positive family history and 80.1% demonstrated the relapsing-remitting (RR) type (16). In a study in southeastern Iran with 206 patients with MS indicated an age range between16–50 years and a prevalence of 13.96 per 100,000. A total of65.8% had the RR type of the disease (17). In capital city of Iran, Tehran, a study of 8,146 patients showed that 72.3% of patients were female and 27.7% were male with a mean age range for disease onset of 27.24 years With the RR type present in 84.9% of patients. The prevalence was reported as 51.9 per 100,000 (18).

Prevalence of MS in Different Cities of Iran Ranked From Highest to Lowest (8)

3.2. Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Other Middle East countries

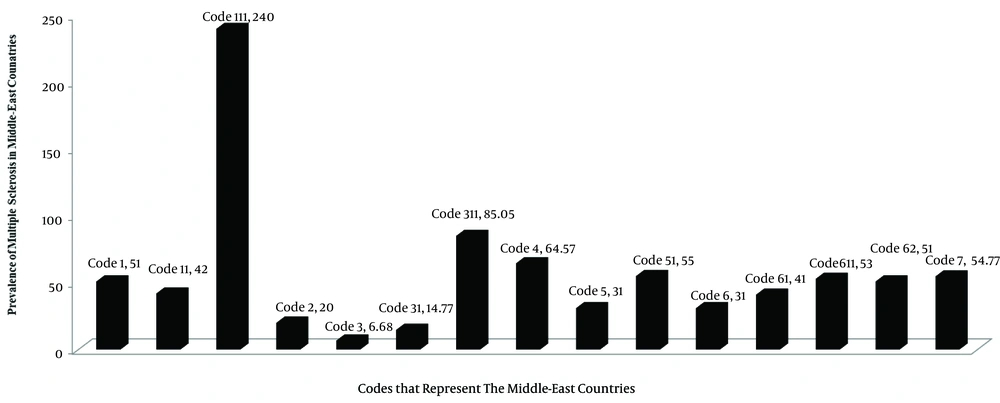

There is a considerable burden from MS in the Middle East as its prevalence emerges to have augmented distinctly in recent decades with a faster rate of increase in female versus male patients (Table 1). Figure 2 shows that Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Oman are the most bordering Middle East countries bordering Iran.

The prevalence data related to Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Bahrain, and Palestine were not available. For Persian Gulf countries, a moderate-to-high prevalence with an increase in incidences in recent years has been reported (2, 3). Figure 3 indicates the study prevalence of MS as related to two communities in Cyprus such as the Turkish-speaking north and the Greek-speaking south have shown the prevalence of MS in Turkish Cypriot men was significantly higher than in Turkish Cypriot women. It was also significantly higher than among Greek Cypriot men. In the Greek-speaking metropolitan area of Nicosia, the prevalence of MS was 51 per 100,000 individuals. The overall MS prevalence in the four areas studied in Greek-speaking Cyprus, including three previously studied, was 42 per 100,000. There was a reported prevalence of 240 per 100,000 individuals for the village named Liopetri in 1991 (9, 19). In Egypt, a study showed that the frequency of prevalence of studied neurological disorders could be ranked as follows: dementia, migraine, stroke, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, cerebral palsy, spinal cord disorders, dystonia, trigeminal neuralgia, chorea, athetosis, and multiple sclerosis. The reported prevalence in this paper for MS was 13.74 per 100,000 individuals (20). Reported data regarding Turkey confirms a prevalence rate of 61, 41, and 53 per 100,000 individuals for Kandira, Geyve, and Erbaa with a total of 51 per 100,000 individuals (21). In another report published in the journal of Neuroepidemiology in 2006, the prevalence of MS in Maltep (a district of Turkey) was accounted as 101.4 per 100,000 individuals (22). Benamer et al. in 2009 reported that in Kuwait, the incidence of MS was 2.08 per 100,000 individuals and prevalence varied from 4 to 42 per 100,000 individuals (7). Alroughani et al. in 2013 reported a prevalence of 85.1 per 100,000 individuals in Kuwait with an incidence of 6.88% (23, 24).

Abbreviations: Code 1: Greek-speaking metropolitan area of Nicosia (1997); Code 11: Four area Greek Speaking Cyprus (1997); Code 111:Cyprus;Village Lioperti (1991); Code 2: Jordan (1997); Code 3: Kuwait (1993); Code 31: Kuwait (2000); Code 311: Kuwait (2013); Code 4: Qatar (2013); Code 5: Saudi Arabia (2013): Code 51: Saudi Arabia (2013); Code 6: Turkey; Kandira (1960); Code 61: Turkey; Geyve (2011); Code 611: Turkey; Erbaa (2011); Code 62: Turkey; total (2011);and Code 7: United Arab Emirates (2011). Iraq, Yemen, Palestine, and Lebanon, are unknown.

4. Conclusions

The search results showed that the epidemiology of MS is quickly changing all over of the world and in the Middle East. It seems that there is a tendency in means of increasing with a doubling in incidences within the female population in the Middle East. In Iran, the highest (n = 93.6) and lowest population (n = 18) of MS was reported for Isfahan and Golestan, respectively (8-11, 15-18). Recent publications confirm that Iran has a moderate to high MS prevalence rate, with a recent sharp increase in this rate (25). Figure 3 shows that other Middle East countries such as the village Lioperti in Cyprus have a prevalence of 240 per 100,000 individuals and Kuwait have a prevalence rate of 85.05 per 100,000 individuals, which seems to show that these areas are high-risk areas. The data related to Kuwait seems to be interesting with a rise in the prevalence from 6.68 to 14.77 to 85.05 reported in years 1991, 2000, and 2013, correspondingly. However, the data related to Iraq, Yemen, Palestine, and Lebanon was not available but it seems that the lowest value related for the prevalence of MS might be related to that of Jordan, which has reported in 1997 a prevalence rate of 20 per 100,000 individuals. Medical explanations point toward many factors such as long-term changes regarding the corpus callosum area or plasma pro-inflammatory proteins such as the novel biomarker Pentrax in 3 levels. The presence of higher levels of depression, the frequency of immunological disease, polymorphisms in the receptors of vitamin D and cytochrome P27B1, the prevalence of infection from the Epstein-Barr virus, the existence of a higher correlation between latitude and the serum vitamin D levels are among the recommended areas to consider for future research in high prevalence areas such as Iran (26-29). According to a recent publication by Iranian scientists, autoimmune family history, MS family history, and personal allergy history are risk factors for MS susceptibility (30). Finally, new treatment strategies are available in Iran due to in biotechnological development. Increased specificity for new drugs in MS might indicate comparable superior value. In patients with PP-MS, SP-MS, or inflammatory RR-MS, cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate might be used in treatment. For those patients who are unable to tolerate conventional therapies, azathioprine could be used. Beta interferons, Avonex, Cinovex, Recigen, Ziferon, and Rebif appear to slow the progress of multiple sclerosis and reduce the severity of attacks with further studies related to pharmacokinetics makes more convenient.