1. Context

Cervical artery dissection (CAD) is a common cause of stroke in young adults. The pathophysiology and treatment of this disease are controversial. This review will highlight the risk factors, pathophysiology, and treatment for this disease.

2. Evidence Acquisition

We performed a PubMed search using each of the keywords: “Cervical artery dissection”, “Dissection”, “Carotid dissection”, and “Vertebral dissection” between January 1st, 1990 and July 1st 2015. We identified evidence-based peer-reviewed articles, including randomized trials, case series and reports, and retrospective reviews that encompass the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, treatment, and outcome of cervical artery dissection.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology

Cervical artery dissection is a common cause of stroke in young adults, with a prevalence of up to 20% in this population and an annual incidence rate of 2.6 to 2.9 per 100,000 (1, 2). The true incidence is likely higher because many cases with dissection may go undiagnosed due to minor self-limited clinical symptoms. In population-based studies, the mean age of occurrence is approximately 45 years and there appears to be a slight gender predisposition favoring males (53 - 57%) (3, 4). Furthermore, there seems to be seasonal variation, with dissection more likely to occur in the winter (5).

Cervical artery dissection is classified based on the artery involved (vertebral vs. carotid) and the location of involvement (intracranial vs. extracranial). The most common type is extracranial internal carotid dissection which typically occurs 2 - 3 cm above the bifurcation and accounts for up to 2.5% of all first strokes (6).

3.2. Risk Factors

Patients with cervical artery dissection are more likely to have hypertension and less likely to have hypercholesterolemia than matched healthy controls (7). In addition, migraine (8-10), particularly with aura, and hyperhomocystenemia (11-13) have been identified as a risk factors for the development of CAD. A history of recent infection is also a predisposing factor (14, 15), and this may partially explain the seasonal variation in the incidence of dissection. Furthermore, certain genetic connective tissue conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome, Osteogenesis Imperfecta, and fibromuscular dysplasia increase the risk of CAD (16-18). One of the important and well-known risk factors that has been identified is a recent history of minor cervical trauma, which has been found to be more frequent in patients with CAD as compared to those with stroke of other types or healthy controls (19).

3.3. Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of dissections depend on the artery involved. Carotid artery dissections typically begin with ipsilateral neck pain or headache and a partial Horner’s followed by retinal or cerebral ischemia. The presence of any two of the three elements in the triad strongly suggests the diagnosis of carotid dissection (20). The headache caused by dissection has no specific features and can resemble migraine or cluster headaches (16). Common headache characteristics include sudden onset, unilateral, constant, and throbbing. Other headache characteristics including a thunderclap headache can also be seen. The Horner is usually partial (miosis and ptosis without anhidrosis) due to the fact that sudomotor fibers of the face travel along the external carotid artery. Focal neurological symptoms as a result of cerebral or retinal ischemia may be transient or persistent and are variable.

Conversely, vertebral artery dissections typically present with occipito-cervical pain, which may be followed by a variety of posterior circulation ischemic symptoms including vertigo, dysarthria, visual field deficit, ataxia, and diplopia. Although strokes from vertebral artery dissection most frequently involve the lateral medulla and cerebellum, spinal cord infarction may occur when extracranial branches are affected.

When intracranial carotid or vertebral dissections are complicated by pseudoaneurysm formation, local symptoms due to compression of adjacent structures can occur. For example, cranial nerves XII, IX and X are closest in proximity to the carotid artery and are those most commonly involved in carotid artery dissection. Furthermore, rupture of a pseudoaneurysm can cause subarachnoid hemorrhage presenting with an acute thunderclap headache and carrying a relatively high mortality and morbidity (21).

3.4. Diagnosis

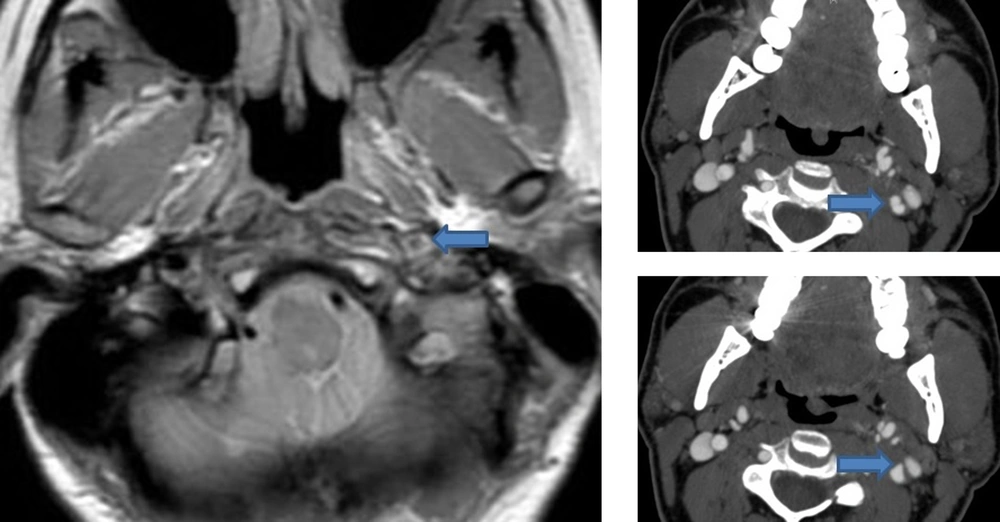

Cervical artery dissection is suspected clinically and confirmed by neuroimaging techniques including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomographic angiography (CT), and conventional angiography. The sensitivity and specificity of each test varies based on the location and extent of the dissection. The preferred method of diagnosis is magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) along with a T1 axial cervical MRI with fat saturation technique due its lack of radiation, high sensitivity and specificity, and ability to visualize an intramural hematoma (Figure 1) (22). CTA also has high sensitivity and specificity and may also be used but is associated with radiation exposure and potential technical challenges (23, 24). In patients with CAD, a CTA can show the double lumen sign (true and false lumen) (Figure 1) or a flame-like taper of the lumen. Carotid ultrasound with color doppler is another screening test that can be used (22). Although it is non-invasive, this technique is operator dependent and is of poor diagnostic value in patients with intracranial carotid dissection and those with vertebral dissections. Although ultrasound has been shown to have high sensitivity in patients with extracranial carotid dissection and ischemic symptoms (25), in patients with headache and isolated Horner this technique is poor (26). A possible explanation is that in patients with local symptoms only, the dissection rarely causes luminal narrowing and thus may be missed on color Doppler (27). Catheter angiogram should not be routinely used to diagnose dissection for several reasons, including inability to visualize intramural hematomas and being an invasive test that may potentially cause an iatrogenic dissection, especially in a patient population with underlying vessel wall weakness.

Left: MRI with fat saturation showing an increased signal and luminal narrowing of the left internal carotid consistent with an intramural hematoma due to dissection. Right: Upper image shows the double lumen sign in the left internal carotid artery suggestive of dissection. Lower image shows a small outpunching in the internal carotid artery consistent with a pseudoaneurysm.

3.5. Pathophysiology of CAD

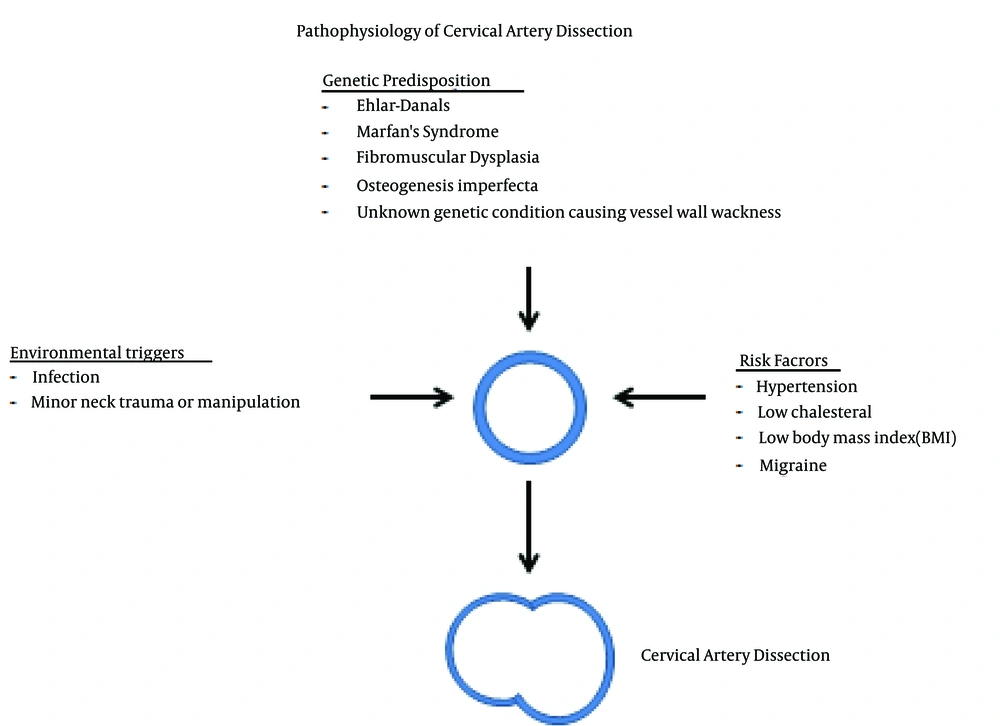

Cervical artery dissection results from a tear in the intima or rupture of the vasa vasorum with bleeding within the media (28) resulting in separation of the vessel wall layers and a false lumen. The hematoma can expand towards the adventitia causing a sub-adventitial dissection, which may be accompanied by a dissecting pseudoaneurysm, or towards the intima resulting in a subintimal dissection causing luminal narrowing (2). The etiology of spontaneous dissection is thought to be multifactorial. Vessel wall weakness is thought to be present in patients with spontaneous dissection who are also more likely to have intracranial aneurysms (29), aortic root dilatation (30), and arterial redundancies (31) which is suggestive of a generalized vasculopathy in those patients. In one study, patients with CAD were more likely to have abnormalities in the adventitia and medial layers of temporal arteries as compared to controls (28). Additionally, skin biopsies have shown a disruption in the morphology of the extracellular matrix in patients with cervical artery dissection, even in those without having a known underlying connective tissue disorder (32, 33). This suggests a genetic predisposition to the occurrence of the disease. Acquired conditions such as minor trauma, hypertension, or a recent infection that may cause vessel wall weakness or injury are also predisposing factors. Taking each of these factors into account, spontaneous cervical artery dissection is thus a condition that typically occurs in patients with a genetic predisposition in the context of an environmental or acquired trigger (Figure 2).

3.6. Pathophysiology of Stroke Due to CAD

Although the exact mechanism of stroke in patients with CAD is unclear, the most likely mechanism is artery-to-artery embolism of a thrombus or fragments of a thrombus that form in the false lumen. This has been demonstrated by brain imaging showing embolic appearing infarcts in most patients with dissection who suffered from strokes (34). Other possible mechanisms include hypo-perfusion causing watershed infarctions if there is severe vessel narrowing, occlusion of the dissected vessel, or, less commonly the intimal flap occluding the ostium of a branch of the dissected vessel. In one study that included 172 patients with CAD out of which 58% had evidence of an acute stroke on diffusion weighted MRI, the mechanism of stroke was found to be thromboembolic in 85% of cases, secondary to hemodynamic failure in 12%, and due to a mixed mechanism in 3% of cases (35). In another study, the presence of luminal narrowing was not associated with stroke occurrence; however patients with occlusive dissection had larger infarcts than those with non-occlusive dissections (36).

3.7. Natural History of CAD

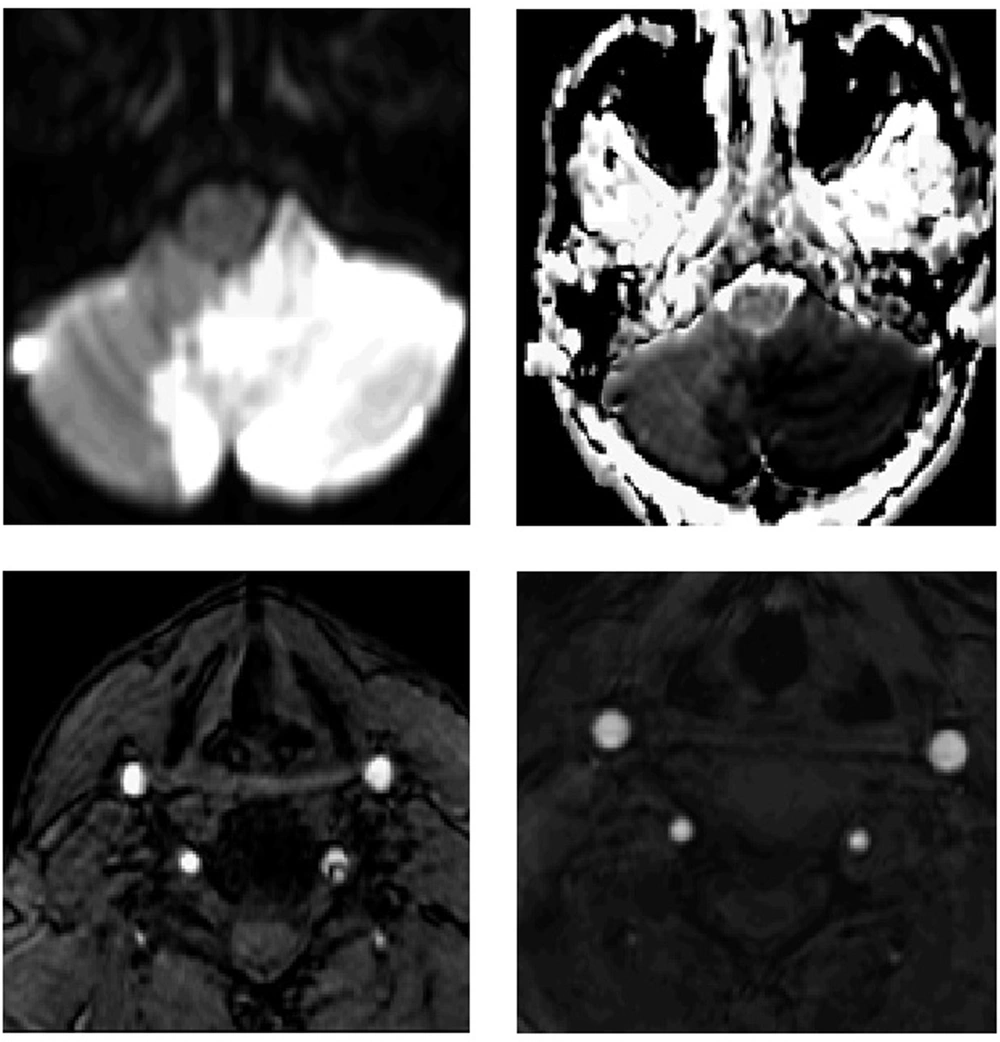

Patients with CAD tend to have a good prognosis. The main predictor of poor outcome is cerebral infarction, which occurs in about 70% of patients with CAD (2), however this is based on data available from stroke centers and thus is subject to referral bias. Strokes related to CAD typically occur in the first 2 weeks after the dissection (37, 38) and the risk of stroke falls dramatically beyond that time point, resembling what is seen with symptomatic carotid stenosis. In population-based cohorts, the risk of recurrent stroke from CAD is less than 3% (37, 38). In general, patients with CAD have resolution and healing of the blood vessel on follow-up imaging 6 months after diagnosis (Figure 3) (39). Although the dissected vessel usually has complete recanalization, residual stenosis or occlusions may persist (2). Even in those who do not recanalize, the risk of stroke recurrence remains very low. One of the complications of CAD is the development of a pseudo-aneurysm that tends to persist on repeat imaging (40). The risk of rupture is around 1% (3, 4) and typically occurs in intracranial vessels lacking an external elastic lamina, causing subarachnoid hemorrhage with a relatively high mortality rate. Although CAD tends to occur only once, about 7% of patients have recurrent CAD seven years from the diagnosis (41). Patients with dissection who have a stroke tend to have a good long-term outcome with 75% being functionally independent at 3 months (16).

He was treated with Aspirin 325 mg daily with full neurological recovery at 3 months. Upper row: Diffusion weighted and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient sequences showing left inferior cerebellar stroke. Lower row: left sided image with magnetic resonance arteriogram (MRA) showing a left vertebral artery dissection; right sided image with MRA in 6 months showing complete resolution of the vertebral artery dissection.

3.8. Rationale for Treating CAD

The main purpose of treating CAD is to prevent stroke. The American heart association (AHA) guidelines state that for patients with dissection with a stroke or transient ischemic attack, antithrombotic treatment for at least 3 to 6 months is reasonable. These guidelines also state that the relative efficacy of anticoagulation versus antiplatelet therapy is unknown (42). Despite that, anticoagulation therapy is still often used in practice as a stroke prevention strategy in patients with cervical artery dissection (43). Anticoagulation has been historically used in stroke prevention without good scientific evidence, which triggered several randomized trials including Warfarin-Aspirin symptomatic intracranial disease (WASID) and Warfarin-Aspirin recurrent stroke study (WARSS) that showed no benefit of Warfarin over Aspirin in reducing stroke recurrence (44-47). The same argument likely holds for cervical arterial dissection where anticoagulation has been historically used in secondary stroke prevention despite the lack of evidence of superiority over aspirin. Several retrospective studies and a meta-analysis did not show any difference between stroke recurrence and bleeding complications between the two treatments (48, 49). While the mechanism of stroke in patients with cervical artery dissection is thought to be artery-to-artery embolism, it is unclear whether or not anticoagulation is the treatment of choice in this instance. In patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, the stroke mechanism involves rupture of an unstable plaque followed by platelet aggregation and thrombus formation on top of a ruptured plaque, which may break off and embolize distally leading to downstream ischemia (34). Even in this instance, anticoagulation has not been shown to be superior to antiplatelet therapy in reducing stroke recurrence risk (50). Although the clot compositions in patients with dissection and atherosclerotic plaque differ, the two entities share a similar stroke mechanism. In patients with cervical artery dissection, the pathophysiology of stroke involves endothelial injury that causes platelet aggregation and activation of the coagulation cascade leading to thrombus formation (51), which may embolize distally causing ischemic symptoms. Therefore, theoretically, inhibiting platelet aggregation with antiplatelet agents or inhibiting the coagulation cascade with antithrombotics is likely to stabilize the thrombus, reduce further thrombus formation, and thereby reduce stroke risk in patients with CAD. This has been translated clinically in a meta-analysis showing no difference in stroke risk between the two treatments (49).

Furthermore, the recently published cervical artery dissection in stroke study (CADISS trial) (52) randomized 250 patients within 1 week from stroke onset to antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. This study showed that there was no difference in stroke risk between the anticoagulant arm (1%) and the antiplatelet arm (3%) (odds ratio 0.335, 95% CI 0.006 - 4 233; P = 0.63). One major limitation of this study is that given the extremely low stroke recurrent rates in the two groups, this study was underpowered to detect a statistically significant difference between the two treatments. Given the enrollment window of 7 days, early recurrent strokes may have been missed.

Thus given the mechanism of CAD, which involves platelet aggregation and activation of the coagulation cascade, its resemblance to symptomatic carotid stenosis in terms of mechanism which typically responds to antiplatelet agents, and the very low stroke recurrence rate, aspirin is likely to be as effective as anticoagulation in reducing stroke risk in patients with cervical artery dissection.

4. Conclusions

Given the relatively rare incidence of this disease, multicenter studies and meta-analyses with collaborative effort among stroke centers worldwide should be considered to enroll patients with cervical artery dissection in a randomized trial comparing the two treatments. This may provide the foundation for an evidence-based approach to the evaluation and treatment of this disease.