1. Context

Autism is a neurological disorder, associated with developmental-behavioral symptoms, such as qualitative impairment in social interactions, language and communication problems, stereotypic behaviors, restricted interests and activities, and sensory processing problems (1). Previously, it was believed that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a rare disorder, with a prevalence of 4 to 6 in every 10 000 people (2). However, current research indicates a higher prevalence of ASD, as reported in about 1 per 88 people (3).

Children with autism may suffer from developmental delays in certain areas, such as cognition, social skills, language, and motor skills (4). One of the affected areas by ASD in children is executive functioning, which is the coordinator of the outcomes of cognitive-motor function and is organized by the prefrontal or frontostriatal region in collaboration with other neural circuits. Therefore, promotion of targeted, planned, flexible, relevant, and timely behaviors can be suitable for these patients (5).

Executive functions include response inhibition, planning, organization, working memory, problem solving, fluency, and attention (6). Studies have shown that people with autism have deficits in specific areas of the brain, including the frontal lobes, limbic system, basal ganglia, parietal lobe, and cerebellum (7). As the frontal cortex and its connections with other brain areas, such as striatal and parietal regions, are involved in a wide range of cognitive functions, the theory of deficiency in executive functions is formed in autism.

The behavioral symptoms of autism in children have adverse effects, such as loss of social relations, social abuse, and reduced standards of living, education, and work experience. In children with autism, behavioral symptoms are very frequent due to behavioral problems, such as temper tantrum, hyperactivity, aggression and physical violence, self-harm, and stereotypic movement disorder (8). Studies have shown that children with autism have deficits in cognitive flexibility, planning capacity, response inhibition, and attention (9); these deficits are more severe in this population, compared to children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (10).

Based on the available literature and theories explaining behavioral symptoms in autism, the theory of executive function deficit in autism can determine the explicit relationship between frontal lobe dysfunction and impaired executive function and explain behavioral symptoms in ASD considering the central role of executive functions in autism.

2. Evidence Acquisition

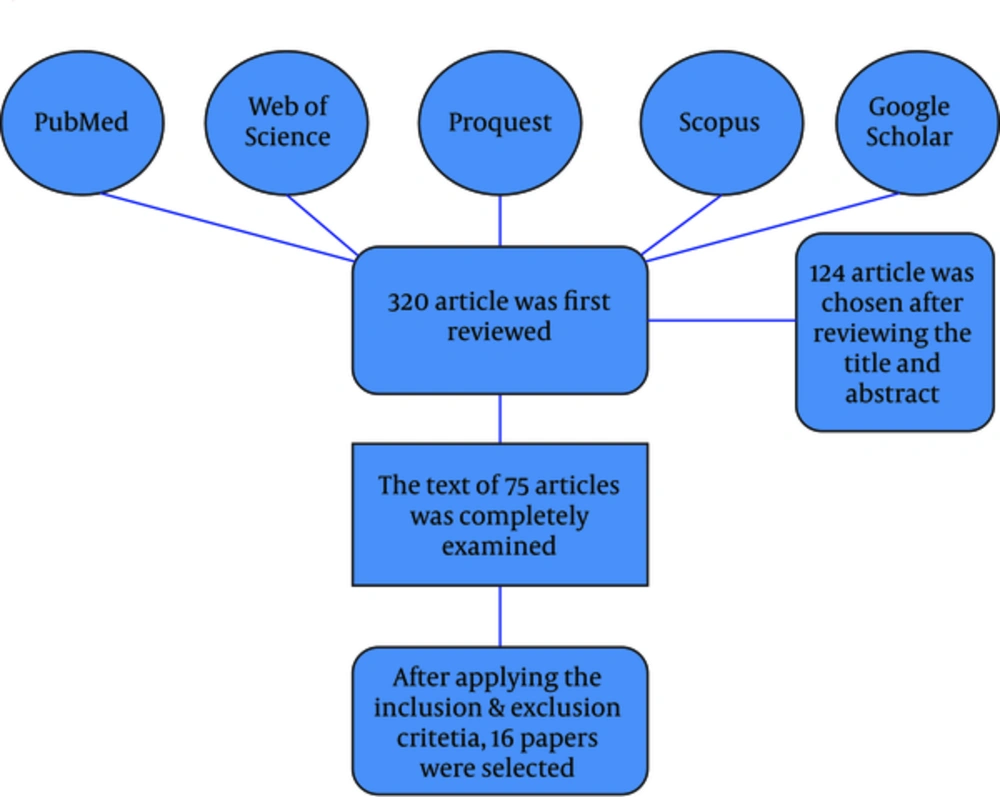

This systematic review was conducted according to the recommendations of Cochrane group and PRISMA guidelines (11). Keywords including “autism”, “executive functions” (e.g., attention and response inhibition), and “behavioral symptoms” were searched in databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, ProQuest, and Web of Science. The search was independently conducted by 2 individuals among articles published before September 15, 2017. The inclusion criteria were studies on executive function in children with autism, while the exclusion criteria were studies on children with autism and other disorders, based on the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) scale (Table 1).

| Type of Research | Scale |

|---|---|

| Systematic review of randomized controlled trials | 1a |

| Individual randomized controlled trials | 1b |

| All-or-none studies | 1c |

| Systematic review of cohort studies | 2a |

| Individual cohort studies or low-quality randomized controlled trials | 2b |

| Outcomes research | 2c |

| Systematic review of case-control studies | 3a |

| Individual case-control studies | 3b |

| Case series, poorly designed cohorts, or case-control studies | 4 |

| Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” | 5 |

The CEBM Scale for Level of Evidence

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) manuscripts written in English and Persian; 2) randomized sham-controlled trials; and 3) available data in the manuscript or upon request for estimation of the main outcomes, i.e., mean (SD) values and response and remission rates. Case series, non-controlled trials, and randomized controlled trials were included in this study, while studies on children with autism and other disorders were eliminated.

2.2. Data Extraction

The following variables were extracted according to a structured checklist, previously elaborated by the authors: 1) metadata (i.e., authorship and publication date); 2) demographics (i.e., sample size, age, and gender); 3) study design (i.e., open-label or randomized sham-controlled studies); and 4) article conclusions.

3. Results

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 16 articles were selected (Figure 1). All articles showed 4 and 5 basis points on the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and had moderate quality (Table 2). Also, according to the CEBM scale for level of evidence, the evidence level of articles was poor to moderate.

3.1. Planning

Planning involves monitoring, evaluation, and continuous improvement and is recognized as a complex and dynamic activity. A person with knowledge of changes in real-life situations and a future-oriented viewpoint selects an appropriate plan, implements it, and then examines its outcomes (12). Generally, children, adolescents, and adults with autism have damaged planning (Tower of London test), which is not eradicated by one's natural development (9).

Specific tests are used to evaluate a person's planning ability, including the Tower of London, Tower of Hanoi, Maze Milner, and Stockings of Cambridge. However, few studies have been performed on planning and its relationship with behavioral symptoms in autism. In a previous study, Brian and colleagues evaluated the general population, using the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS), Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS), Aberrant Behavior Checklist, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. The study showed correlations between planning and stereotypic symptoms and repetitive behaviors (13).

3.2. Cognitive Flexibility

Cognitive flexibility refers to one's ability to perform different tasks in response to reposition or change one's way of thinking (14). Dysfunction in cognitive flexibility is associated with preservation, stereotypic behaviors, and activity adjustment problems (15). Children with autism have problems with cognitive flexibility tasks and are unable to change their way of thinking in face of a changing environment (16). The tests used to assess cognitive flexibility include Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST), Shifting Attention Test (SAT), and intradimensional/extradimensional (ID/ED) shift task from Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB).

Based on a study by Shiri et al. (2015), cognitive flexibility deficit in children with high-functioning autism was significantly correlated with stereotypic behaviors, communication problems, and social interaction symptoms (17). Brian and colleagues found a significant relationship between cognitive flexibility and stereotypic behaviors (13). Moreover, South M et al. and Yerys et al. found a relationship between stereotypes and impaired cognitive flexibility (15, 18). In addition, Turner et al. conducted a study to examine the relationship between defective cognitive flexibility and autism symptoms and found a relationship between cognitive flexibility and repetitive behaviors in these children (19).

Berger reported that cognitive flexibility is an important factor in predicting autism, which can be used for social understanding and social competence (20). In addition, in a review study by Hilde et al., defective cognitive flexibility was considered a central defect in children with autism (10). According to previous studies, stereotypic behaviors and communication/social issues have a significant relationship with impaired cognitive flexibility and can explain the symptoms of children with autism.

3.3. Response Inhibition

The ability to inhibit inappropriate responses and impulsivity is known as response inhibition (21). There are several tests to evaluate response inhibition in autism, using the Stroop test, Go/No-Go tasks, stop-signal tasks, negative priming, and Hayling test. According to the literature, children with autism are deficient in inhibitory control, while substantial evidence shows that response inhibition remains intact in autistic children (9, 16). Research conducted by Stroop test, Go/No-Go task, and stop-signal task showed no defects in response inhibition among children with autism. One of the reasons for the variations in the results of this study may be the application of different tests.

Based on a study by Shiri et al. (2015), response inhibition in children with high-functioning autism is correlated with communication and social interactions (17). Brian and colleagues found that behavioral stereotypes are significantly related to response inhibition (13). In addition, Katharine et al. (2008) found a relationship between repetitive behaviors and control for a targeted response, as confirmed in other studies (19, 22, 23). According to the literature, repetitive and stereotypic behaviors are related to response inhibition deficits.

3.4. Working Memory

Another component of executive functioning in children with autism is working memory. Working memory is involved in organizing various aspects of memory, involving purposeful behaviors. Besides problem-solving skills and growth, communication and achievement of immediate goals are activated in working memory. The working memory is assessed by the amount or number of codes a person can maintain simultaneously. The ability to retain and process information at the same time is a function of working memory.

Based on the Baddeley's model of memory, working memory consists of 3 parts: 1) visual-spatial circuit, 2) phonological circuit, and 3) central circuit (24). The central circuit is responsible for the transfer function between tasks, inhibition of incorrect responses, retrieval of strategies, and strengthening of selective attention. The N-Back test was used to evaluate working memory. Previous research suggests impairments of working memory in autistic children at different ages (25).

Substantial research has been conducted on the central circuit, while other circuits are not accurately examined (26). In a study by Brian and colleagues, working memory had a significant relationship with stereotypic behaviors (13). Moreover, according to a study by McEvoy et al., working memory deficits are associated with social interaction problems (27). Joseph and Tager-Flusberg (2004) also evaluated the false-belief task in the theory of mind and executive function tests. Although they could describe the variance in communication problems, none could explain the variance in social interactions and stereotypic behaviors (28).

According to a study by Gilotty, there is a relationship between working memory and adaptive behaviors; there is also an association between communicative and social skills and executive functioning (29). Therefore, executive functioning is strongly associated with play, communication, and social skills in autistic children. It seems that data on working memory are contradictory, and further research is required to establish any relationship with behavioral symptoms.

3.5. Attention

Attention is the most important aspect of human cognition and is known as concentration and consciousness about a task. There are different types of attention, including sustained, selective, divided, and shifting attention, which are controlled by a specific brain region (30). Various attention tests are available for the assessment of different attention types, including continuous performance test (CPT), Stroop test, and SAT (31).

Based on previous studies, autistic children have deficits in divided (32), shifting (33), sustained (34), and selective (35) attention. Dysfunctions in the frontal lobe of autistic individuals and failure in sustained attention might contribute to impairments in sustained attention. Considering the relationship between attention and behavioral symptoms, Shiri et al. (2015) indicated an association between sustained attention dysfunction, stereotypic behaviors, and social interactions (36). LeMonda, R Holtzer, and S Goldman (37), Lopez et al. (13), and South et al. (15) have conducted research on the relationship between attention and behavioral symptoms.

In a study by Geraldine Dawson et al. on autistic children, it was concluded that impaired divided attention is associated with social relations (38). Children with high-functioning autism require an active attention transfer between a class of information and other relevant data. In a previous study, these children showed great preservation, and fewer complementary classes were reported on SAT (39); one of the reasons for preservation may be disruption in the frontal brain circuits for inhibition of cognitive functions (40).

As to the relationship between shifting attention and behavioral symptoms in autistic children, the literature suggests that shifting attention is an important component of executive functioning. This component can predict the normal development of the theory of mind and social interactions in autistic children (41). In addition, impairment of executive functions, including shifting attention and cognitive flexibility, is directly related to people's ability to respond and develop an adaptive manner, based on the situation and social symptoms (13). According to these findings, shifting attention seems to play an important role in the symptoms of autism.

Bishop and Norbury (2005) suggest that impairment of practical language in autism may be due to communication and social problems. Selective attention and executive dysfunction may have negative effects on a child's ability to regulate behaviors during social interactions (limits on the length and quality of children's relationships with peers) (42). The ability to control impulsive responses, attention to objective stimuli, and appropriate behavioral and emotional responses are important and require appropriate response inhibition and selective attention (34).

4. Discussion

According to the findings, challenging behaviors, such as stereotypes, are considered as debilitating patterns in autistic children (43). Appropriate executive function seems to play a major role in the development of cognitive, behavioral, and socioemotional patterns (44). Ozonoff et al. (2004) suggest that deficits in executive function play an important role in the etiology of autism (45). Happe (2006) showed that functions of autistic children (average age, 10 years) improved in the theory of mind within 2 months after training of executive functioning, while autistic children with training for the theory of mind showed no improvements in their skills (46).

The discussed findings support the important role of executive function in the development of the theory of mind skills, normal communication, social interactions, and purposeful behaviors, which require intact executive functions (41). In all these areas, symptoms of autism, such as response inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and changes in performance and attention, require appropriate treatment. Hughes et al. (2000) suggest that good social communication can be supported by relationship between executive function and theory of mind (41).

According to the literature, restricted and repetitive behavioral patterns are associated with cognitive flexibility, working memory, and response inhibition, but are not associated with fluency and planning. Moreover, in other studies, executive function deficits are introduced as the first model to explain repetitive and restricted behaviors (13, 47, 48). Also, executive dysfunction has negative effects on language development and social systems (49).

The frontal symptoms include lack of social motivation, poor interactions, and repetitive behaviors; these characteristics are among the symptoms of autistic disorder (50). Executive functions originate from the frontal and prefrontal brain regions and may have a relationship with behavioral symptoms (9); however, there have not been any studies on behavioral symptoms and communication. It seems that evaluation of behavioral symptoms, associated with executive function deficits, can introduce a new approach for the treatment of children with autism.

| Level of Evidence | PEDro Scale | Results | Procedure | Age | Control Group | Experimental group | Year of Publication | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2b | 5 | The left inferior part of the orbitofrontal region (motion inhibition), left insula (inhibition of interference), and parietal lobe (set shifting) activities are correlated with EF. | Go/No-Go test, fMRI, task switching, and Stroop test | --- | 12 NL | 10 ASD | 2006 | Schmitz et al. (7) |

| 2b | 5 | CF, working memory, and RI have a significant relationship with SB and RB in autism. | DKEF, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, GARS, and Aberrant Behavior Checklist | 19 to 42 y | 17 NL | 17 ASD | 2005 | Lopez et al. (13) |

| 2b | 5 | There is a relationship between RB and CF, while there is no correlation between RB and central correlation. | WSCT, Gestalt Closure Test, and Group Embedded TestTest | 10 to 19 y | 18 NL | 19 HFA | 2007 | South et al. (15) |

| 3b | 4 | There is a significant relationship between RI, communication signs, and social interaction. There is a significant relationship between CF and communication symbols, social interactions, and SB. | Stroop test, CF scale, Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ), and GARS | 7 to 12 y | - | 50 HFA | 2015 | Shiri et al. (17) |

| 2b | 5 | There is a significant relationship between the amount of errors in ED and RB, as well as CF and nonsocial symptoms. | ID/ED shift test | 6 to 13 y | 84 NL | 42 HFA | 2009 | Yerys et al. (18) |

| 3b | 4 | CF versus central cohesion can be predictive of the social symptoms of autistic individuals. | Central coherence, CF scale, and several aspects of social functioning symptom severity, social intelligence, social competence, and social functioning after 3 years | Young adults | - | 30 HFA | 2003 | Berger et al. (20) |

| 2b | 5 | There is a relationship between SB, sensory problems, and executive dysfunction. In children at young age, sensory issues can predict SB in the future. | Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised, sensory questionnaire, and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning | 6 to 17 y | 64 NL | 61 ASD | 2009 | Brian et al. (21) |

| 2b | 5 | Cortical defects of the anterior cingulate cortex formation lead to defects in RI, which can cause RB and SB in autism. | Diffusion tensor imaging and MRI | 27 to 30 y | 14 NL | 10 ASD | 2008 | Thakkar et al. (22) |

| 3b | 4 | Higher-level cognitive-language processes in the theory of mind, EF, and social-perceptual processes are related to the behavioral symptoms of autism, including social interactions. | Expressive Vocabulary Test, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III, perception/knowledge unexpected-content false-belief tasks, and word span, block span, day–night, and knock–tap tasks | 5 y and 7 m to 14 y and 2 m | --- | 31 ASD | 2004 | Tager-Flusberg (28) |

| 2b | 5 | There is a relationship between working memory and adaptive behaviors. Communication and social skills are also related to EF. There is a strong relationship between EF and play deficits, communication, and social skills. | Behavioral rating inventory of EF, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, and two parent reports of everyday functioning | - | - | 35 ASD | 2002 | Gilotty et al. (29) |

| 3b | 4 | There is a significant relationship between selective attention and communication and social interactions. There is also a relationship between sustained attention, social interactions, and SB. Shifting attention also has a significant positive relationship with communication, social interactions, and SB. | Stroop test, CPT, SAT, ASSQ, and GARS | 7 to 12 y | - | 50 HFA | 2015 | Shiri et al. (36) |

| 3b | 4 | Defects of social interaction in autism are associated with the lack of joint attention. | Shared attention and orienting tasks | 30 m to 64 m | 20 NL | 20 ASD and 20 Down’s syndrome | 1998 | Geraldine et al. (38) |

| 2b | 5 | EF was associated with the theory of mind. | Emotion perception task, picture sequencing task, appearance-reality task, mental and physical distinction tasks, brain function task, M&M false-belief task, second-order belief attribution, Tower of Hanoi, and WCST | 8 to 20 y | 20 NL | 23 ASD | 1991 | Ozonoff et al. (39) |

| 2b | 5 | There is a significant relationship between the percentage of correct answers on the fluency test and communication skills. There is a relationship between spoken operational problems and social interactions. Also, the ideation problem is associated with autistic communication. | Children Communication Checklist, measurement of autistic symptoms, and ideational fluency tasks | 6 to 10 y | 18 NL | 25 speech problem and 18 ASD | 2005 | Bishop and Norbury (42) |

| 2b | 5 | One’s inability to complete the CANTAB test cannot predict the severity of symptoms in children with autism, but is associated with adaptive behaviors. | CANTAB, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Wechsler Intelligence Scales, and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | 6 to 47 y | 70 NL | 79 ASD | 2004 | Ozonoff et al. (45) |

| 2b | 5 | There is a poor relationship between EF and RB. | Verbal fluency task, concept generation task–child version, Rey Test, Test, walk, don’t walk task, and RB questionnaire | 7 to 16 y | 18 NL | 19 ASD and 17 OCD | 2009 | Zandt et al. (47) |

The Review of Retrieved Articles

4.1. Limitations

Among the limitations of this study was the age of the subjects; accordingly, further research on children's age is required.

4.2. Recommendations

Due to limited studies on behavioral symptoms and executive function, further analysis is recommended. Also, in some areas, such as planning, working memory, and fluency, future research is suggested.