1. Background

Through the use of emotion regulation strategies, a key mechanism by which life events can have an effect on psychological distress and mental health indicators (1). Although there are a variety of known emotion regulation techniques, expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal are among the most widely used (2). Expressive suppression involves blocking the expression of emotions in a situation that elicits emotions. Cognitive reappraisal involves reevaluating thoughts about the situation that triggers emotions in order to reduce the negative impact (3). Studies generally indicate that expressive suppression is associated with higher levels of psychological distress and stress-related mental health issues (4). Systematic reviews and empirical evidence have shown that individuals who are anxious or depressed tend to use expressive suppression more frequently and effectively, compared to cognitive reappraisal. Anxiety disorders, in particular, are characterized by a high reliance on expressive suppression and a limited use of cognitive reappraisal (5, 6). Suspending has been linked to poor social outcomes on several occasions. In a study of face-to-face contact, experimentally controlled suppression was found to have negative effects, including poor interpersonal coordination, decreased feelings of rapport and affiliation, and increased negative feelings about the interaction, among other things (7).

Emotional regulation takes place at the physiological, psychological, and social levels, and it has "typical" developmental trajectories. Experiments and experiences can alter these trajectory paths throughout the life cycle. According to research, adversity in childhood disrupts the typical neural pathways involved in emotion regulation (8). According to previous research, expressive suppression has been shown to increase stress reactivity in trauma-affected individuals. Moreover, trauma exposure is often positively associated with the use of expressive suppression, according to previous research. In addition, previous research indicates that prior trauma or hardship can have a negative effect on mental health by influencing the use of emotion regulation techniques. For instance, experiencing childhood adversity, such as emotional neglect, was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms due to a greater reliance on expressive suppression. Additionally, it was found that increased depressive symptoms were linked to less frequent or ineffective use of cognitive reappraisal in individuals who had experienced childhood adversity (9). Mental health problems, on the other hand, tend to appear earlier with greater severity, higher rates of comorbidity, and less favorable responses to treatment for individuals with maltreatment histories than their non-maltreated counterparts (10). For individuals who have been subjected to sexual abuse, physical assault, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and/or emotional neglect in childhood, cumulative risk analyses show that exposure to stress in adolescence can be particularly predictive of mental health problems (11).

In previous studies, the majority of them did not examine different forms of childhood trauma in each case, so we investigated a variety of forms of abuse and neglect, including sexual assault, physical assault, emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect. Similarly, most recent studies have examined the development of mental disorders as a result of childhood trauma.

2. Objectives

However, the present study aims to predict the use of suppression as an emotional regulation tool in Iranian adolescents based on trauma-related experiences. This is also the first study in Iran.

3. Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted cross-sectional among Iranian adolescents who are internet users. For attracting participants, the convenience sampling technique was used. The questionnaires were made online and their links were sent to the children. The subject matter of the study and the anonymity of responses were also discussed in several lines and sent to the students as part of the questionnaires. Twenty people were excluded from the study, out of 370 participants who completed the questionnaires, because they did not meet the inclusion criteria of being an adolescent (aged 12 to 17), the ability to read and write, and having access to the internet.

3.1. Ethical Approval

The research proposal was approved by the research committee of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, with IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1399.787 ethics code. Prior to participating in the research, all participants were informed about this research and any ethical considerations relevant to the study and filled up informed consent forms.

3.2. Childhood Traumas Questionnaire (CTQ)

In 2003, Bernstein developed this questionnaire to assess childhood traumas. This questionnaire is used as a screening tool for revealing facts about childhood neglect and abuse. This questionnaire can be used by both children and adults. Using this method, five types of childhood traumas are analyzed, including sexual assault, physical assault, emotional abuse, and emotional and physical neglect. The questionnaire contains 28 questions, of which 25 are used to measure the main components of the questionnaire, and 3 of them are used to identify people who deny their childhood problems (12). For the dimensions of emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual assault, sexual harassment, emotional neglect, and emotional neglect, Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.87, 0.86, 0.95, 0.89, and 0.78, respectively (12). In Iran, Ebrahimi (13), increased Cronbach's alpha for each of the five components from 0.81 to 0.98. In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas for the CTQ and its subscales were as follows: Total scale = 0.93; emotional abuse = 0.76; physical abuse = 0.84; sexual abuse = 0.89; emotional neglect = 0.76; and physical neglect = 0.76.

3.3. Gross & John Emotion Regulation Scale (ERQ)

Gross and john developed this scale to measure emotion regulation tactics. This scale consists of ten items and two subscales, which include: Reappraisal and suppression. The answers are based on a 7-degree Likert Scale (from the opposite to the most agreeable). For the whole scale, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.79 for reappraisal and 0.73 for suppression, and 0.69 after 3 months. Another researcher obtained the validation of this questionnaire in Iran in 2018, and Cronbach's alpha was reported to be higher than 0.7.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in two descriptively and inferentially levels. At the descriptive level the mean and standard deviation were reported for each variable and at the inferential level, hypotheses were tested using Pearson's correlation and stepwise regression analysis. Before conducting the regression analysis, its 3 assumptions were evaluated. These include the absence of uni and multivariate outliers, the normal distribution of the criterion variable (i.e., suppression), the linear relationship between criterion and predictor variables, and the absence of multiple collinearities. Inspecting the standard scores indicated that some participants had z-scores > 3 or < -3 on some variables (0 participants on suppression). However, Mahalanobis distances indicated 9 multivariate outliers. In total, eleven participants were excluded due to being the uni and multivariate outliers. Therefore, the final sample included 302 participants. The histogram of suppression showed a close-to-normal distribution. Inspecting the scatter plots revealed a linear relationship between of suppression and predictors. Finally, since the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance statistics were lower than 3.5, multiple colinearity was not present among the predictors. After ensuring these statistical assumptions, stepwise regression analysis was carried out. It should note that 39 participants were excluded from study because had denied their childhood problems based on validity scale of Childhood traumas questionnaire all analyses were conducted utilizing SPSS version 24.

4. Results

The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The final sample included 302 adolescents. Their ages' mean was 16 (SD = 1.37). Among them, 36.4 % (n = 110) were female and 63.6% (n = 192) were male. Majority (51%) of adolescents were in their seventeenth. Finally, 88.1% of participants lived in families with equal or lower than 10 - 15 million Toman monthly income.

| Demographic Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age | 16 ± 1.37 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 110 (36.4) |

| Male | 192 (63.6) |

| Income | |

| 1 - 5 million Toman | 68 (22.5) |

| 5 - 10 million Toman | 121 (40.1) |

| 10 - 15 million Toman | 77 (25.5) |

| 15 - 20 million Toman | 23 (7.6) |

| More than 20 million Toman | 13 (4.3) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

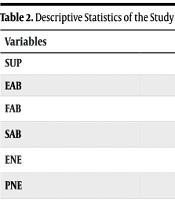

The descriptive statistics of the study variables and the correlations between them are presented in Table 2. As is evident from Table 2, suppression had negative correlation with physical and sexual abuse.

Abbreviations: SUP, suppression; EAB, emotional abuse; FAB, physical abuse; SAB, sexual abuse; ENE, emotional neglect; PNE, physical neglect.

a P < 0.01.

A stepwise regression analysis was conducted to identify the best predictors of suppression. The results are reported in Table 3. As is evident from Table 3, the regression model involved one step. Based on the standard coefficients in the final model, physical abuse was the predictor.

In the first step, physical abuse was entered into the model (b = -0.316, β = -0.75, P < 0.001) and predicted 3 % of the suppression’s variance. The final model implies that adolescents with higher scores on physical abuse, use less suppression as an emotional regulation strategy.

| Predictor | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | T | P | Model's Adjusted R2 | 95.0% Confidence Interval for b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | Β | B | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Constant | 17.692 | 0.615 | - | 28.764 | 0.000 | 50.302 | 16.482 | 18.903 |

| Physical abuse | -0.316 | 0.067 | -0.375 | -4.740 | 0.000 | 0.027 | -0.447 | -0.185 |

5. Discussion

In an experiment of Iranian adolescents, the present study sought to determine the correlation between childhood trauma experiences and the use of suppression as an emotional regulation tool. Physical assault predicted suppression, according to the results obtained in this study. And explained 3% of its association. A case study investigated the relationship between elements of the family context and children and adolescents' emotional regulation (er). The study was based on a tripartite model of familial influence. Firstly, it is suggested that children learn about er by observational learning, simulation, and social inquiry. Secondly, parenting skills that are specifically related to emotion and emotion management impact the er. Er is influenced by the family's emotional environment, which includes parenting style, attachment relationship, family expressiveness, and the marital relationship (10). Researchers investigated the socialization of children's emotion regulation in physically maltreating and non-maltreating mother-child dyads. Maltreating mothers used less validation and emotion coaching as well as more denial in response to children's emotions, according to the study (14) maltreating mothers used less validation and emotion coaching than non-maltreating mothers (14). They can therefore be expected to have difficulties in encoding and decoding emotions, which requires the ability to recognize emotional expressions of others and to produce clear, appropriate emotional displays (15). Therefore, it can be said that in the first stage, a person must recognize emotions in order to suppress it. For this situation, perhaps the term emotional confusion is more appropriate than suppression.

The negative association between physical assault and the use of suppression seems odd at first glance, considering that we expected that abuse would result in more use of this ineffective emotion regulation mechanism. However, a societal perspective suggests that these consequences can be mitigated by cultural values. In a two-part study, butler tested this hypothesis and found that habitual suppression was associated with self-protective goals and negative emotion in Americans with western-European values. When individuals with more Asian values were suppressed, their deleterious effects were reduced, and these reductions were mediated by cultural differences in the suppressor's response. According to these findings, many of suppression's negative social consequences can be mitigated by cultural values (16). The negative correlation is no longer far from expected from this point of view.

New research suggests that the benefits of emotion regulation should be based on the context in addition to a cultural perspective. Socioeconomic status (ses) is a key contextual moderator because it plays a vital role in people's lives: Lower ses gives less control over one's environment, and therefore, the ability to self-regulate should be particularly important (17). The obtained results seem to be justified because the bulk of the samples examined in this study were considered to be of a low socioeconomic status.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this report shows a predictive relationship between physical abuse and the acquisition of suppression among Iranian adolescents. Studies such as the present study are necessary for clinical planning because of the crucial role of emotion regulation strategies in psychiatric disorders.

5.2. Limitations

Although our study provides new insights regarding risky sexual behaviors in adolescents, several limitations should be considered in interpreting findings. First, the role of other factors such as the child's temperament, the number of family members, living with both biological parents or not, and the length of time they were maltreated were not investigated, which are recommended to be addressed in future studies. Second, the data collection process was carried out by using self-report measures rather than actual behaviors that could be biased due to the respondents' inaccuracy in answering the questions.