1. Context

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a pandemic by March 11, 2020. The disease has become a global public health concern, affecting more than 7,000,000 cases and causing 414,000 deaths globally (1-3). COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that belongs to a family of RNA beta-coronavirus 2b lineage (3, 4). This new coronavirus may cause coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that is accompanied by numerous symptoms, including pneumonia, dry cough, fever, myalgia, lymphopenia, and breathing difficulty (3-5). The virus was first detected in Wuhan, China, in early December 2019 (4).

SARS-CoV-2 shows genomic structural similarities to other coronavirus family members like BatCoV RaTG13, bat-SL-CoV ZC45, and bat-SL-CoV ZXC21 (6-10). Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 genome, structural and non-structural protein, life cycle, and interaction with the host are important subjects for researchers to find the best targets for designing candidate vaccines and drugs (5, 11-15). Although several products have entered clinical trials that are in progress, currently there are no approved therapeutics, drugs, and vaccines against COVID-19 (16). Most of these therapeutics are designed based on the available data on SARS coronavirus, while our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis is limited (17).

One of the challenges about COVID-19 is its effect on different organs, showing its ability for interaction with similar receptors expressed in related cells. Detection of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as the main known receptor for SARS-CoV-2, which can be expressed in the lungs, heart, kidneys, endothelium, intestine, and brain, supports the reported multi-organ injury in the infected patients. These damages also could be explained indirectly by oxygen depletion and induction of severe inflammation in these tissues (12, 13, 15). Analysis of histological changes in autopsy and biopsy of patients, together with clinical information and data as to the cellular and molecular immunology of COVID-19, will reveal a more complete picture of the infection and its pathogenesis. The current scoping review tries to synthesize early findings on the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 to assess emerging therapies and vaccines by evaluating their impact based on the mechanism of pathogenicity. The study was designed due to the lack of any reliable protocols for the treatment of the disease and vaccines or other immunization drugs for its prevention.

2. Methods

In this review, the three databases of PubMed, Scopus, and google scholar were searched. In order to make this search extensive and sensitive, only the words “corona” and “immunology” were searched in the three databases, but this search was limited to studies from January 2020 until March, 15 2020. Quality assessment was performed and only thematic relevance was considered for the selection of the articles. To extract the results from the studies, the content thematic analysis method was used. In this method, the topics studied were coded in the articles and then classified into four main areas, including “Genome structure similarity to other coronaviruses”, “virus entry inhibition and immune response”, “vaccine and treatment targets”, and “pathogensis”.

Qualitative analysis was performed based on thematic content analysis and included the evaluation of overlap and coverage of content, the degree of consistency or inconsistency of the results, and the topics that have been most emphasized in the studies.

3. Results

Out of the 2250 articles retrieved, after deleting duplicates and reviewing their thematic relevance, 45 were selected for final analysis. Entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells and related components for interaction with the host were emphasized in seven studies (Table 1). As summarized in Table 2, antibody-dependent enhancement, increased interaction of the virus with host cells through mutation of surface proteins, cytokine storm and inflammation, and diminished T lymphocytes count were reported as possible mechanisms for the virus immunopathogenesis.

| Mechanisms | Viral Components-Host Cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Virus entry | S protein-ACE2 | (18) |

| Virus entry | Receptor binding domain (RBD)-ACE2 | (19) |

| Virus entry | RBD (residue 493)-ACE2 (Lys31) | (3) |

| Virus entry | S1 subunit-ACE2 | (14) |

| Membrane fusion | Six-helical bundle (6-HB)-host cell membrane | |

| Virus entry and spread | S2-TMPRSS2 protease | (20) |

| Virus entry | S1 RBD (unique phenylalanine F486)-ACE2 (hydrophobic pocket) | (21) |

| Virus entry | Linear surface exposed non-glycosylated epitopes in RBD-ACE2 | (22) |

Mediators of SARS-CoV-2 and Host Cell Interactions

| Disorders | Mechanisms | Viral Structure | Host Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained inflammation, lymphopenia, and/or cytokine storm | Antibody dependent enhancement (ADE) through prior exposure to othe SARS-CoVs | Not declared | Immune system | (13) |

| Infection enhances the cleavage efficiency | An insertion sequence in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 | SPRR insertion in the S1/S2 protease cleavage sites of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein | pulmonary alveoli, intestinal and esophagus epithelium were also the target tissues of SARS-CoV-2 | (12) |

| Inflammation and severe lung pathology | Activation of Th1, high expression of GM-CSF and IL-6 by pathogenic monocytes | Not declared | T helper 1 lymphocytes and inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes | (15) |

| Severe respiratory illness | Diminished T lymphocytes and elevated cytokines | Not declared | Lung tissue | (6) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome | Cytokine storm, T cell exhaustion, IL-10 overexpression | Not declared | T cells | (23) |

Preliminary Data on the Immunopathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2

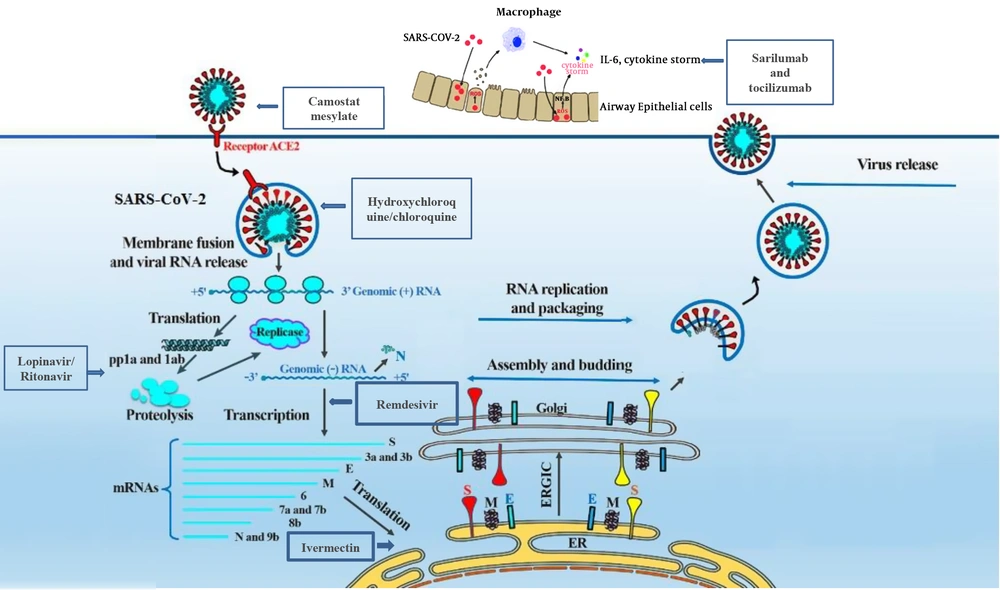

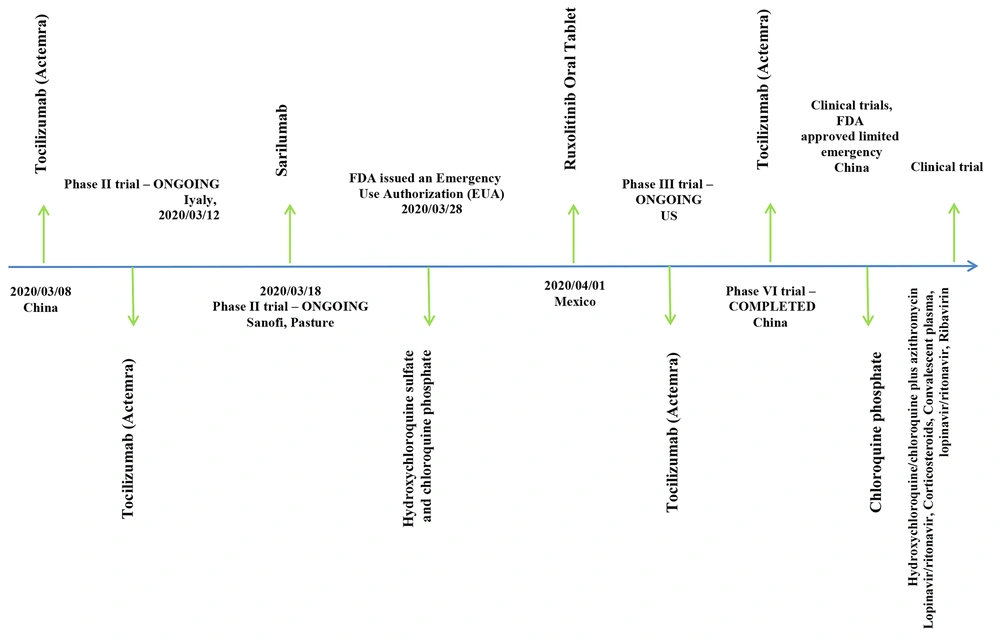

In the studies proposing vaccines and other immunization routes against COVID-19, monoclonal neutralizing antibodies (5 studies), CoV fusion/entry inhibitors (1 study), and epitop based vaccines (5 studies) were presented (Table 3). Drugs against the infection were reported in six studies (Table 4). These drugs could target fusion, entry, replication, and spread of the virus (Figure 1). While the results of clinical trials for candidate vaccines and therapeutics were not presented in any of the published articles, a list of nine ongoing trials is presented in this review (Figure 2).

| Product | Steps of the Pathogenesis | Viral Life Cycle | The Viral Targets | Proposed Application (Candidate Vaccines & Therapeutics) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monoclonal neutralizing antibodies | Entry | Viral fusion | Spike glycoprotein (S) | Vaccines | (5) |

| 2 | CoV fusion/entry inhibitors | Fusion | Viral fusion | HR2 and HR1 domain in spike protein | Vaccines | (14) |

| 3 | Epitop based vaccine | Entry and Release | Fusion and assembly | Spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) | Vaccine | (24) |

| 4 | Dewetting monoclonal antibodies | Virion impairment | Spread | viroporin channels | Vaccine | (25) |

| 6 | Neutralizing antibody | Entry | Attachment | S protein | Vaccine | (20) |

| 7 | Monoclonal antibody | Immuopathology | - | GM-CSF or interleukin 6 receptor | Vaccine | (15) |

| 11 | Potential B and T cells epitopes | Entry | Attachment and fusion | S protein | Vaccine | (26) |

| 12 | Potential neutralizing antibodies, B-cell epitopes, and peptide vaccine candidates | Spread | Viral entry and immune response | S, ORF1ab, ORF3a, M protein | Vaccine | (27) |

| 14 | Putative B and T cells epitopes | Entry, fusion, and assembly | Induction of immune response | S, E, and M | Vaccine | (28) |

| 15 | Synthetic long peptide vaccine | Entry and assembly | Induction of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immune response | S and M proteins | Vaccine | (29) |

| 16 | Putative epitope vaccines | Entry, processing, assembly | Interaction with B and T cells | ORF1, N, S | Vaccine | (23) |

| 19 | Linear surface-exposed epitopes | Entry | Viral attachment | Spike protein | Vaccines | (22) |

Candidate Vaccines for COVID-19

| Product | Steps of the Pathogenesis | Viral Life Cycle | The Viral Targets | Proposed Application (Candidate Vaccines & Therapeutics) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monoclonal neutralizing antibodies | Entry | Viral fusion | Spike glycoprotein (S) | therapeutics | (5) |

| 2 | CoV fusion/entry inhibitors | Fusion | Viral fusion | HR2 and HR1 domain in spike protein | therapeutics | (14) |

| 5 | Prulifloxacin, Nelfinavir, Bictegravir, and Tegobuvir have high binding capacity with SARS-CoV main protease | Genomic and protein processing | Replication and proliferation | Block of viral main protease | Therapeutics | (18) |

| 10 | Remdesivir | Replication | Viral transcription | RNA-dependent RNA polymerases | Therapeutics | (30) |

| 12 | Potential neutralizing antibodies, B-cell epitopes, and peptide vaccine candidates | Spread | Viral entry and immune response | S, ORF1ab, ORF3a, M protein | therapeutics | (27) |

| 19 | Linear surface-exposed epitopes | Entry | Viral attachment | Spike protein | therapeutics | (22) |

Candidate Treatment Choices for COVID-19

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Structure and Similarity of COVID-19 with Other Coronaviruses

At the amino acid level, SARS-CoV-2 is quite similar to SARS-CoV and has a genome size of ~30 kilobases (24, 34). SARS-CoV-2 belongs to Betacoronaviruses with 96.2% similarity, in a clade composed of MERS-CoV (about 50% sequence homology), SARS-like bat CoV (96.2%), and SARS-CoV (80% - 88.2% sequence identity with 98% coverage) (11, 21, 34-36). The similarity between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 was estimated as 96.3% (10, 12, 18). The closest homolog of SARS-CoV-2 is a SARS-like coronavirus isolated from bat (MG772933.1) with 87.99% at 99% coverage (21). Whole spike glycoprotein and its receptor-binding domain (RBD) share 76% and 72% sequence identity with SARS-CoV, respectively, and a total of 22 predicated N-glycosylation sites found in the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2, which are shared by SARS-CoVs (21).

The virus contains 14 open reading frames (ORF) that encode 27 proteins. The ORF1AB and ORF1A genes encode 15 non-structural proteins (NSPs). The viral genome also encodes S, E, M, and N structural proteins and accessory proteins 3a, 3b, p6, 7a, 7b, 8b, 9b, and orf14. Results showed > 90% identity in proteins E, M, and N and accessory proteins 7 and Orf14, of which E protein was more conserve (98.7% identity). Based on the phylogenetic analyses, it was shown that pp1ab, pp1a, envelope, matrix, accessory protein 7a, and nucleocapsid genes of SARS-CoV-2 show high similarity with SARS-like bat CoVs (34).

In a study that compared homology of bat-SL-CoVZC45 and bat-SL-CoV ZXC21 with SARS-CoV-2, 87.9% and 87.2% identity was determined at the genomic level, respectively. The lowest identity was related to S protein (64% - 68% and 93% homology for the S1 and S2 subunits, respectively) (37, 38). Other mutations, except for those detected in the spike protein contained within some regions of the RBD, are observed in NSP3 and NSP2 and some of the accessory proteins. In a study by Shu et al., a higher substitution rate of ORF1ab and spike protein was shown, most of which were similar to bat-CoV-RaTG13, pangolin-CoV, and SARS viruses.

Substitution in spike-S1 was characterized in SARS-CoV-2 specifically. Higher affinity of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the wild-type spike, containing the V354F amino acid substitution was proposed as the cause of its super infectivity (39). Bioinformatics analysis showed that an insertion in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 could increase its cleavage by S1/S2 protease, a phenomenon that could explain its higher pathogenicity. Compared with SARS-CoV, the insertion sequence small proline-rich protein (SPRR) at the S1/S2 cleavage site, which could be used as the more appropriate substrate for transmembrane protease serine (TMPRSS) protease, could increase the cleavage rate of the S protein that enhances its infectivity. While no amino acid substitutions were detected in the receptor-binding motifs that are responsible for interaction with ACE2 and other receptors for the virus entry, some mutations were characterized in other regions of the RBD (39).

Moreover, coexpression of ACE2 and TMPRSS protease in pulmonary alveoli, intestinal epithelium, esophagus, and epithelium of the colon explained the ability of this virus to infect several tissues (12). The spread of the virus to these tissues can support recent findings about a long time shedding of the virus in the stool of patients at the convalescent phase. Deletion in the complete frame of the protein 8a, and deletion and insertion of several amino acids shown in proteins 3b and 8b, respectively, are among other mutations reported in SARS-CoV-2 (8, 34). Further studies are needed to examine the effects of these mutations on the infection rate of SARS-CoV-2 in different populations, the severity of the pathogenesis, and interference with the induction of immune response.

4.2. Cellular Entry of Virus to the Host Cell

Currently, different theories have been presented about the cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 to the host cell. There are some viral components and host receptors that are described for this virus (Table 1). It was shown that this virus does not use some specified receptors, like aminopeptidase N and dipeptidyl peptidase 4, like other coronaviruses, but can exploit angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the surface of host cells for its entry (2, 18). SARS-CoV-2 can promote interaction with the host cell receptor through the receptor-binding domain (RBD) on its spike protein. This receptor is specific for lineage B beta coronaviruses (i.e. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2). Protease treatment can enhance the ACE2 entry of clade 2 RBD (19).

A cellular protease known as TMPRSS2 seems to be responsible for spike protein priming that could facilitate its fusion, entry, and/or progression of the infection in infected patients (2, 3, 10, 14, 18-22). SARS-CoV-2 recognizes ACE2 in a variety of animal species that could serve as intermediate hosts for humans.

Some RBD residues on the spike protein are critical for interaction with ACE2, which could be exploited for drug design. Among them, N-terminal domain (aa14-305), receptor-binding domain (aa319-541), receptor-binding motif (aa437-508) in S1 subunit, (aa14-685) and fusion peptide (aa788-806), HR1 (aa912-984), HR2 (aa1163-1213), transmembrane domain (aa1214-1237), and a cytoplasmic domain (aa1238-1273) in S2 subunit (aa686-1273), are involved in the fusion mechanism with ACE2 receptor on host cells (14).

Mutation in some of these residues, such as Gln493 in RDB of SARS-CoV-2, could interfere with its interaction with the human ACE2 receptor, suggesting the involvement of virus-binding hotspots on this receptor (3, 22). It was shown that hydrophobic amino acid L472 is also important for the interaction between RBD and ACE2 that is involved in the virus entry into cells (21). There is a lack of data about other binding domains on SARS-CoV-2 and host cell receptors to describe difference in organ tropism and susceptibility to the infection at different age groups.

4.3. Pathogenesis and Host Immune Response

Several mechanisms have been proposed for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis (Table 2). This virus is able to promote lymphopenia and sustain inflammation (13). Analysis of lung autopsy of infected patients with SARS-CoV-2 showed large numbers of pathogenic immune cells that suggested immune-mediated damage as the main cause of organ dysfunction and death in these patients. Occurrence of severe pulmonary inflammation and cytokine storm can be promoted by SARS-CoV-2 through the activation of CD4+T lymphocytes that generate GM-CSF and induce CD14+CD16+ monocytes that can produce high amounts of IL-6 (15). Acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock, hypoxemia, acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, and cardiac injury, as well as secondary infection by bacteria and fungi, can occur during COVID-19. Laboratory findings, including lymphopenia (lymphocyte count decreases significantly in severe cases), elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and ferritin in severe cases, higher concentrations of IL-2R, TNF-α, and IL-10, lower absolute number of total T lymphocytes, and lower expression levels of IFN-γ, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, by CD4+ T cells, could support the noted extensive organ injuries in severe cases of COVID-19, especially in elderly patients (≥ 60 years of age) and those requiring intensive care unit (ICU) care (6, 40).

4.4. Vaccination and Treatment

Scientists are working on different targets to design a vaccine or provide therapies against COVID-19 (Tables 3 and 4). Some of these candidates can affect different steps of the virus entry. Among the proposed candidates, a computational analysis showed 405 likely T-Cell epitopes on S protein, with strong MHC-I and MHC-II presentation scores and 2 potential neutralizing B-Cell epitopes (27). The capacity of the spike protein and the ability of its related epitopes such as T-cell (Good MHC presenter) and B-cell epitopes was also described by other studies (5, 11).

TMPRSS2 inhibition is the other target that can block the entry of the virus into host cells (20). SARS-CoV-2 employs this protease for S protein priming, which is necessary for interaction with ACE2. Moreover, the design of neutralizing antibodies interfering with two electrostatic clips predicted at the interface between ACE2 and the SARS-CoV spike protein RBD was suggested in a study (22, 41). RBD and ACE2 n are the essential steps for virus attachment and entry into the host cell. Characterization of unique amino acid residues on the S protein, like phenylalanine F486 that is placed in its flexible loop that strongly interacts with F28 in ACE2, increased hopes for the production of effective treatments (21).

The design and construction of antibodies as treatment options was also proposed by other studies. In a study, the production of a high-affinity antibody equiped with lipophilic structure was suggested against viroporin channels. This antibody could cause virion impairment preventing its attachment to human cell membrane receptors (25).

Induction of immune system elicited by candidate vaccines and medications was proposed as an alternative option to combat COVID-19. In a study by Qamar et al., reverse vaccinology technique was used, which predicted 23 linear B cell and 16 T cell epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 surface glycoprotein, envelope protein, and membrane glycoprotein with diverse antigenic potentials through immunoinformatics approaches. The study also suggested two antigenic epitopes for MHC class I and II (28).

In a similar study by Baruah et al., immunoinformatics approach was used to identify cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) and B cell epitopes in SARS-CoV-2 surface glycoprotein (26). In a study by Bojin et al., doing population-based vaccinomics was proposed for vaccine design against SARS-CoV-2. Accordingly, sequences of spike and membrane proteins were analyzed, and multiepitope peptide vaccine candidates that can potentially prompt both CD8+ and CD4+ cell-mediated immune response with the specified tendency to HLA-type of each population was suggested (29). In a study by Zhou et al., the production of GM-CSF by activated TCD4+ cells following infection with SARS-CoV-2 and interleukin-6 secretion by the induced inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes was considered as the mainstay of severe pulmonary inflammation and cytokine storm (15).

In a study by Zhu et al., patterns of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 strains and their possible effects on the immune vulnerability of a population was studied. The study was aimed to show the ability of viral immunogenic epitopes with the lowest mutations to induce class I and II MHC presentation to properly elicit CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses. The results of this study showed the existence of some mutations among different strains that could alter the immune vulnerability landscape of this virus, which should be considered in the development of vaccines and therapies (23).

Main protease (also known as nsp3) and nucleotide analogues are among the other targets for the design of drugs or vaccines against COVID-19. In a study by Li et al., a similarity of 96.1% was detected between the sequences of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV main proteases (18). The study suggested four small molecular drugs as promising candidates with high binding capacity to SARS-CoV main protease; these drugs included including Prulifloxacin, Bictegravir, Nelfinavir, and Tegobuvi. In a study by Gordon, it was shown that nucleotide analogues can affect RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp) by inhibition of RNA synthesis (30). The researchers proposed the same strategy for the design of equivalent MERS-CoV antiviral constructs against SARS-CoV-2.

WHO, CDC, and other international medical centers and infectious diseases societies are updating the latest news about designing new drugs and vaccines against COVID-19. As shown in Figure 1, these drugs can block the virus entry (Camostat mesylate), S protein/ACE2 interaction and membrane fusion (umifenovir, also known as Arbidol), protease inhibotors, viral RNA transcription (remdesivir), cytokine storm (sarilumab and tocilizumab, which block IL-6 production), and membrane fusion (hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine that change the pH of acidic intracellular organelles, including endosomes/lysosomes, which are essential for the membrane fusion, and viral replication) (Ivermectin, through its nuclear transport inhibitory activity). Most of these drugs are subjected to a global clinical trials by the WHO, which is known as a megatrial called SOLIDARITY.

The development of a vaccine seems to be the most effective strategy for the prevention of COVID-19. Recent supportive data about the protective effects of plasma from curred patients at the convalescent phase increased promise for vaccine development. While a review of reports about candidate COVID-19 vaccines is beyond the scope of this review, we tried to present the main products that are at the clinical trial stage (Figure 2) (42).