1. Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is characterized by the morphology of cancer cells with a reciprocal chromosomal translocation (15;17) (q22;q12-q21) and coagulopathy. The recommended treatment includes anthracycline-based chemotherapy (i.e., daunorubicin and idarubicin), cytarabine, and all-transretinoic acid (ATRA) (1). ATRA syndrome is a multisystem disorder characterized by shortness of breath, fever, weight gain, hypotension, and high permeability of pulmonary microcirculation. This condition is commonly seen in patients with APL, after the administration of ATRA at a rate of 2% - 27% (2).

SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia could mimic ATRA syndrome by its similar clinical presentations and imaging findings. SARS-CoV-2 infection usually manifests with mild upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms and may lead to lower respiratory tract involvement and multi-organ failure. The mortality of this disease ranges between 0.2% and 15%, depending on age, underlying diseases, comorbidities, secondary bacterial infection, and timely diagnosis and treatment of the disease (3).

The duration of onset of symptoms is generally between 2 days to two weeks., and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the point-of-care diagnostic testing for this condition (4). Primary diagnosis could usually be made based on clinical signs and symptoms, epidemiologic links with the index case, and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan. Here, we present the case of an APL patient during the COVID-19 pandemic, who primarily presented with an acute respiratory illness suspected to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

2. Case Presentation

A 7-year-old boy referred to our center with a chief complaint of easy bruising for one month. On admission, white blood cells (WBC) count was 3,200 cell/mm3 (i.e., 20% neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, 2% eosinophils, and 60% promyelocytes), hematocrit was 36.2%, and platelet was 20,000 cell/mm3. On peripheral blood smear, numerous fragmented red blood cells were found.

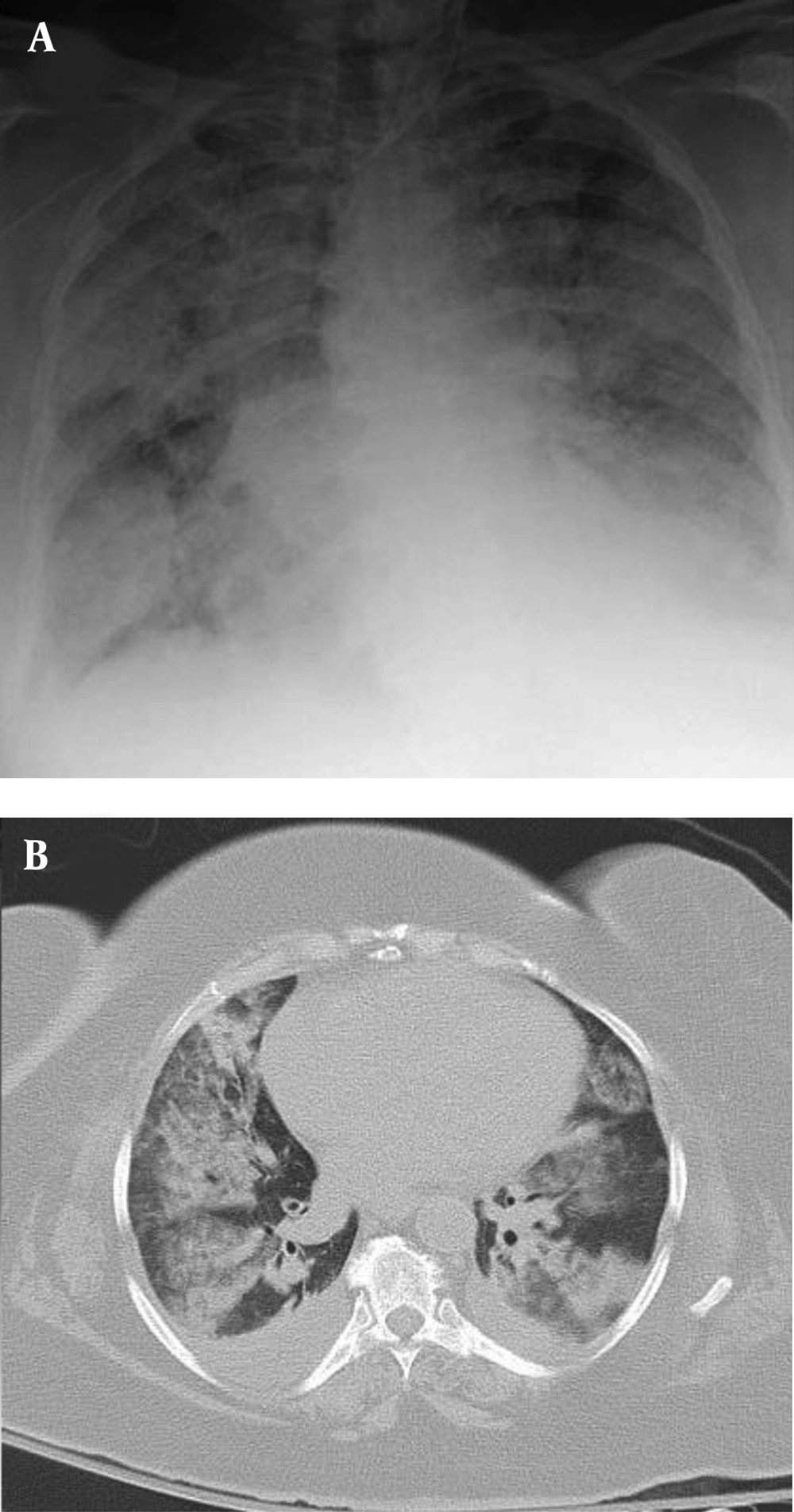

Bone marrow (BM) aspiration/biopsy showed hypercellularity with a marked increase in promyelocytes (80%).The diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia was confirmed by bone marrow cytogenetics, which was positive for (t[15;17][q22;q12]] translocation, and the patient was treated with ATRA 45 mg/m2 on day one and intravenous idarubicin 10 mg/m2 on days 7, 9, and 11. After three days, he developed fever, respiratory distress, low systolic blood pressure, and extremity edema. A chest X-ray was performed, which revealed bilateral pulmonary infiltration (Figure 1A), and a chest CT scan demonstrated mixed ground-glass opacity (GGO), consolidation with peripheral distribution, and pericardial effusion (Figure 1B). Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine increased, and the patient became oliguric.

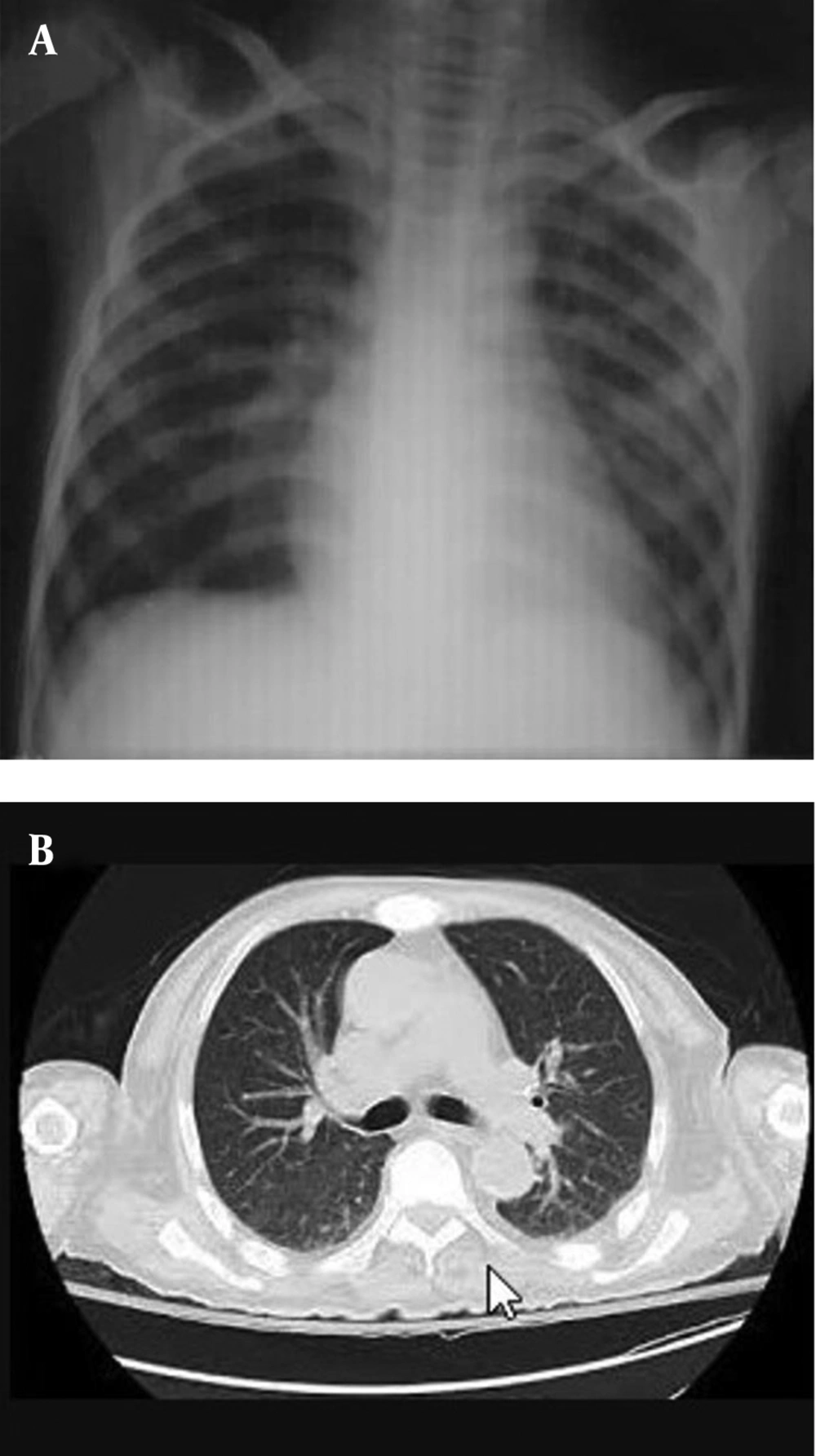

SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was repeatedly negative for the patient and his family members. After ruling out COVID-19 pneumonia, the diagnosis of ATRA syndrome was suspected, and ATRA was discontinued, and parenteral dexamethasone 2 mg every 8 hours was started accordingly. The patient’s symptoms improved dramatically after the discontinuation of ATRA and starting dexamethasone. He was subsequently given cytarabine and idarubicin at a subtherapeutic dose. Radiologic findings significantly improved after the treatment modification and corticosteroid therapy (Figure 2).

3. Discussion

ATRA or differentiation syndrome is characterized by fever, hypoxemia, lung opacities, pleural effusion, and pericardial effusion in a patient treated with ATRA (5-7). Differentiation syndrome is a life-threatening condition usually seen in patients with APL. The reported incidence of ATRA syndrome varies between 2% and 27% in different clinical trials on patients receiving ATRA (8).

ATRA prevents releasing inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL) 6 and IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) from leukemic cells. The pathogenesis of ATRA syndrome is not completely clear, but it seems some vasoactive inflammatory cytokines lead to capillary leakage (9). The maturation of promyelocytes and tissue infiltration of these matured cells is the next declared etiology (10). The final mechanism of injury is endothelial damage, followed by edema, bleeding, fibrinous exudates, leukocyte infiltration, and finally, respiratory failure (8).

The pathogenesis of the SARS-CoV-2 infection is almost similar to ATRA syndrome with cytokine storm, diffuse alveolar damage, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (11, 12). Tubular epithelial cells of the kidney, the central nervous system, and various types of immune cells may also be impaired. It seems that both abnormal immune responses and cell injury may be critical factors in SARS-CoV-2 infection (13, 14).

The diagnosis of ATRA syndrome is usually made after excluding other differential diagnoses such as viral and bacterial infections. The mortality rate of this condition varies between 8% and 28%, and dexamethasone is the recommended treatment (15, 16).

In our patient, bacterial and fungal blood cultures were negative. COVID-19 PCR was also negative in the patient and his family. The patient was treated with corticosteroids and responded quickly by reducing the symptoms and radiological disturbances. This rapid response to glucocorticoids is consistent with the diagnosis of ATRA syndrome, while steroids may lead to worsening of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Routine use of systemic corticosteroids for COVID-19 pneumonia is discouraged in the updated guidance released by the World Health Organization (WHO) on May 18, 2020 (17), because of the possibility of prolonged viral replication, as seen in middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) pneumonia, unless there is another reason for use, for example, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or septic shock (18).

As with previous illnesses, such as severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (SARS) and MERS, corticosteroids are not commonly recommended as they may exacerbate COVID-19-related lung damage (19). Based on the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of corticosteroid therapy on various outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV infection, no significant effect on reducing the risk of death, reducing hospitalization days, ICU admission rate, and use of mechanical ventilation could be found (20).

Preventive steroid therapy during induction therapy with ATRA is not routinely recommended; however, despite the lack of supportive evidence in randomized trials, based on some case series, preventive strategy with corticosteroids is proposed in those with leukocyte count > 5 - 10 × 109/L (21).

Chest radiographs of ATRA syndrome also mimic COVID-19 pneumonia. GGO (60%), consolidation, nodular opacities, and pleural effusion can be seen that may be similar to COVID-19 pneumonia or other lung infections (22, 23). GGO, with or without consolidations, is the most common CT finding in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (24-26). Chest CT abnormalities are usually bilateral, with lower lobes preference and peripheral distribution. Other less common findings include pleural effusion, hilar lymphadenopathy, crazy paving pattern, cavitation, interlobular septal thickening, and linear opacities (26, 27).

It has been shown that chest CT scan is more sensitive than RT-PCR in the early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia, and CT scan usually shows abnormal findings up to seven days before positive results of RT-PCR assay (27). Therefore, it is essential to rule out other differential diagnoses because symptoms, lab data, and imaging findings may overlap with other diseases. Pneumonia, pulmonary thromboembolism, and heart failure are the most important differential diagnoses of ATRA syndrome (28).

3.1. Conclusions

COVID-19 infection is a multisystem disease with clinical and imaging similarities to ATRA syndrome. A high index of suspicion is necessary when treating patients receiving ATRA during the COVID-19 pandemic. While corticosteroids are the treatment of choice for patients complicating with ATRA syndrome, they may be harmful in patients with COVID-19.