1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) is a novel virus that has affected millions of individuals across the world. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was officially declared as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (1-3). This disease most frequently is manifested as viral pneumonia characterized by symptoms such as fever, dyspnea, and cough. However, extrapulmonary and atypical presentations, such as gastrointestinal, neurologic, and cardiovascular involvement, as well as thromboembolic events, have been reported amongst COVID-19 patients (4-7). Herein, we present a patient referred to Namazi Hospital, Shiraz, Iran, with an impression of gastroenteritis whose COVID-19 PCR turned out to be positive and progressed to purpura fulminans (PF).

2. Case Presentation

A 3-year-old, full-term, and fully immunized female was referred to Namazi Hospital with a history of fever, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting since five days prior to admission. The patient was very ill. However, her mother reported no symptoms regarding respiratory infections, and she had no signs of respiratory tract involvement. The patient had no definite COVID-19 exposure history.

On physical examination, her pulses were not detected. Thus, her blood pressure could not be measured. The patient's respiratory rate was 38 per minute, and the temperature was 38.2°C. Her arterial oxygen saturation was 74% in room air. The patient was lethargic and had a decreased level of consciousness. The patient's height and weight were 90 cm and 8 kg, respectively. Some ecchymotic lesions were all over the body, especially in sites where blood was drawn. Both hands and feet were cold, pulseless, mottled, and covered by ecchymosis, particularly in more distal parts (Figure 1). Her fingers were cyanotic, and capillary refill time was delayed for more than 3 seconds. No other abnormal signs were detected in physical examination. Table 1 showed the laboratory data of the patient.

| Lab Data | On Admission | 1 Day After Admission | 2 Days After Admission | 1 Week After Admission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC, /mm3 | 1900 | 1900 | 1300 | 1900 |

| Hb, gm/dL | 9.4 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 4.8 |

| MCV, fL | 72.7 | 71.2 | 71.4 | 74.9 |

| Platelet, /mm3 | 37,000 | 38,000 | 89,000 | 216,000 |

| PT, sec | 21.9 | 26.4 | 22.2 | 20.4 |

| INR, index | 1.62 | 1.96 | 1.64 | 1.51 |

| PTT, sec | 28.4 | 120 | 41.4 | 39 |

| Blood sugar, mg/dL | 30 | |||

| B.U.N, mg/dL | 15 | 25 | ||

| Cr, mg/dL | 0.7 | 0.3 | ||

| Na, mEq/L | 151 | 154 | 165 | 158 |

| K, mEq/L | 3.2 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 5.5 |

| Ca, mg/dL | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.8 | |

| P, mg/dL | 2.1 | |||

| Mg, mg/dL | 2.3 | 1.4 | ||

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 3.1 | |||

| AST, IU/L | 26 | 75 | ||

| ALT, IU/L | 39 | 68 | ||

| ALK.P, IU/L | 235 | 191 | ||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| Direct bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.3 | 0.3 | ||

| Total protein, g/dL | 4.2 | 4.7 | ||

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.4 | 2.9 | ||

| LDH, IU/L | 812 | 1810 | ||

| ESR, mm/h | 13 | 50 | ||

| CPK, IU/L | 163 | |||

| CRP, mg/L | > 150 | > 150 | 136 | |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 510.7 | |||

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 2.22 | |||

| Urine protein | Negative | 2+ | Negative | |

| Urine Hb | 1+ | 1+ | Negative | |

| Random urine Cr, mg | 42 | |||

| Urine random Na, mEq/L | 13.6 | |||

| Blood culture | No growth | |||

| Urine culture | No growth |

aOf note is the significantly prolonged PT, INR, and PTT.

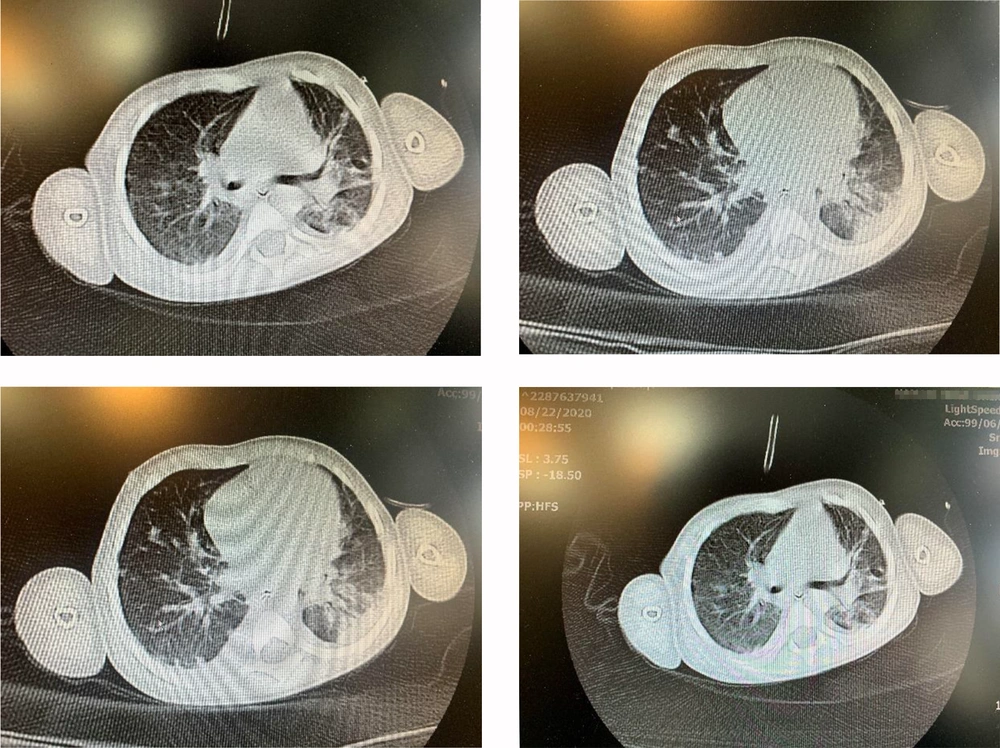

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the PCR of COVID-19 was done on samples of the pharynx and nasopharynx of the patient, which turned positive. Spiral HRCT of lungs showed patchy ground-glass and patchy consolidations in the upper and lower lobes of both lungs, which was in favor of COVID-19 infection (Figure 2). The patient had undergone echocardiography, which revealed a mildly dilated left ventricle and good biventricular function. On the second day after admission, a peripheral blood smear was taken, which showed leukopenia (lymphocyte dominant), hypochromic RBCs, moderate Burr cell count, a few acanthocytes, and severe thrombocytopenia as well as a few large platelets. Based on the pediatric hematologist and pediatric ICU specialists’ recommendations, vasopressors and management of PF were started promptly. The patient was transferred to the pediatric ICU after a few hours.

Unfortunately, despite all efforts, due to the severity of the disease, the patient passed away a few days later.

3. Discussion

PF is a rare, life-threatening disorder of acute onset skin lesions due to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) and small vessel thrombosis of the dermis, which is characterized by hemorrhagic infarction of skin (8). DIC triggers systemic activation of blood coagulation resulting in excessive blood clotting, which leads to endothelial injury. As the condition progresses, clotting factors and platelets are consumed in widespread intravascular coagulation, which can result in severe bleeding (9). Although bacteria such as Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most common microorganisms that cause PF, viruses can rarely cause it (10). Shah et al. (11) explained a rare association of purpura fulminans with West Nile Virus infection. Thomson et al. (12) reported varicella zoster infection in a patient that progressed to PF. Antibodies against protein S occur, and protein S deficiency induced by varicella-zoster infection can be the etiology of PF in this patient (12, 13). According to research that assessed maternal deaths due to infectious cause, there was a significant association between the influenza A (H1N1) virus and purpura fulminans (14). Clinical patterns of COVID-19 patients with DIC are varied, from petechial to acro-ischemia presentations. Hypercoagulable states in DIC are associated with these cutaneous manifestations. Purpura fulminans is a combination of hemorrhagic and thrombotic presentations, which can occur in severe COVID-19 patients (15, 16).

The patient was visited on September 19, 2020. To the best of our knowledge, up until now, no published COVID-19 case with PF is presented in the literature, and this appears to be the first reported case of COVID-19 and PF.