1. Context

The SARS-CoV-2 infection, termed COVID-19, has spread very quickly and affected all ages, even newborns (1, 2). Initially, there was a misconception among the researchers believing that the virus does not affect children. However, it was then proposed that children are usually asymptomatic or present mild symptoms, but a complete immunity cannot be proposed for this age group (3). Since late April 2020, multiple studies from Europe and the United States showed that 2% - 6% of SARS-CoV-2-infected children exhibited a severe multi-system inflammatory syndrome with similarities to Kawasaki disease (4-6).

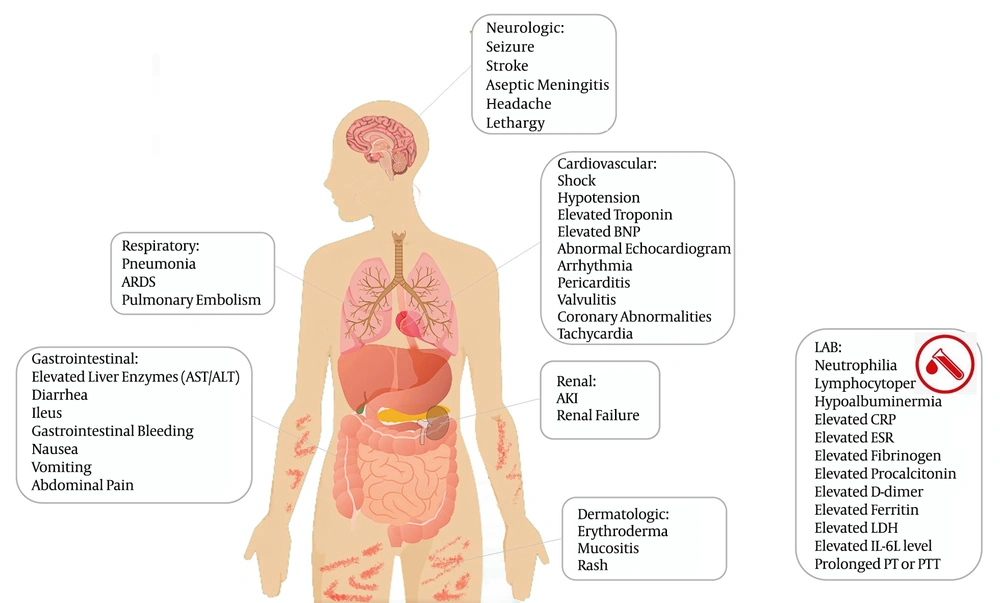

As there is no comprehensive testing, the true incidence of this severe condition in pediatrics has remained unclear. This significant hyper-inflammatory response can cause cardiovascular disorders, and some of these children may deteriorate faster and need admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) due to cardiogenic shock or acute left ventricular dysfunction (7). Apart from cardiac manifestations, various clinical symptoms have also been reported, including neurological, renal, significant gastrointestinal (GI), and mild respiratory symptoms, as well as rashes and stomatitis (8). Although it is still not fully understood whether this multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a primary complication of COVID-19 infection or a post-infectious complication, a correlation is highly suggestive based on epidemiologic data (7).

There is little information about the cardiac involvement associated with COVID-19 in pediatric cases, and most of the studies on cardiac involvement are case reports or case series. It is also possible that children with an underlying cardiac disease are at a higher risk of experiencing severe cardiac complications following the COVID-19 infection (9). Reports on MIS-C have shown coronary artery involvement, myocarditis, ventricular dysfunction, hemodynamic instability, and PICU admission, all of which suggest that cardiac dysfunction might be a notable risk factor for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatrics (10). Therefore, a literature review in this regard would be beneficial. This study aimed to review and summarize the available evidence on the potential cardiac clinical presentations in children with MIS to give a better perspective on management and care for these patients.

It should be noted that different terms have been used to refer to this novel condition, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), hyper-inflammatory shock in children with COVID-19, “Coronasacki”, “Kawashocky”, Pediatric COVID-19-associated inflammatory disorder (PCAID), and pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome (PMIS) (7). In this review article, we continue to use the term MIS-C.

2. Methods

A literature review was conducted by searching PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The following keywords were used for the search: “Pediatrics”, “children”, “heart”, “cardiac”, “Coronavirus disease-19”, “COVID19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “systemic inflammatory response syndrome”, “multisystem inflammatory disorder in children and adolescents”, “MISC”, “PMIS”, “PCAID”, “Coronasacki”, and “Kawashocky”. We included case reports and case series related to MIS-C associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The inclusion criterion was defined as being a case report or case series reporting some findings of cardiac involvement in pediatrics with COVID-19. Articles published in languages other than English and those irrelevant to our objectives, like commentaries, other reviews, and letters to editors, were excluded. The last search was performed on September 30, 2020. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) (11) for the quality assessment of the studies, and those with top quality were enrolled. The baseline data including the first author’s name of the article, number of cases, age, sex, past medical history, ethnicity, clinical signs and symptoms, and the type of COVID-19 diagnosis confirmation (PCR or serology) were extracted. Moreover, the laboratory, electrocardiography, and echocardiography findings were gathered.

3. Definition of MIS-C

The three definitions of MIS-C, by the World Health Organization (WHO) (12), the Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) (13), and the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) (14), are presented in Table 1. The presence of fever, multisystem organ involvement without alternative plausible diagnoses, laboratory evidence of inflammation, and recent exposure to a COVID-19 case or evidence of COVID-19 infection are the key elements in all MIS-C cases. But, some signs, including fever duration and organ involvement, vary among these criteria.

| WHO | CDC | NHS-the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0 - 19 | < 21 | Children |

| Fever | Fever ≥ 3 days | Subjective persistent fever ≥ 24 hours or documented fever > 38.0°C for ≥ 24 hours | Persistent fever > 38.5°C |

| Clinical findings | Mucocutaneous inflammation signs (e.g., stomatitis), bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis or rash, shock or hypotension, ventricular dysfunction, valvulitis, pericarditis, or coronary involvement (including an increased level of NT-proBNP /troponin or echo findings), acute GI manifestations, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, or vomiting | Evidence of clinical deterioration requiring hospital admission, in addition to multiple (≥ 2) organ dysfunction (renal, dermatologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, GI, hematologic, or neurologic) | Single or multi-organ dysfunction (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, GI, hematologic, dermatologic, or neurologic). Oxygen requirement and hypotension have been reported in most kids. Other features, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, conjunctivitis, rash, sore throat, cough, respiratory symptoms, headache, confusion, lymphadenopathy, stomatitis, neck swelling, hands and feet edema, syncope have been seen in some children. |

| Laboratory findings | Elevated inflammatory factors (e.g., CRP, ESR, or procalcitonin) evidence of coagulopathy in laboratory data (PT, PTT, INR, and D-dimer) | Elevated ESR, CRP, LDH, procalcitonin, fibrinogen, D-dimer, ferritin, IL-6, hypoalbuminemia neutrophilia; lymphocytopenia | Abnormal fibrinogen level, hypoalbuminemia, high D-dimer and ferritin amount Some: acute kidney injury, anemia, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, elevated IL-6, elevated IL-10, hypertransaminasemia, proteinuria, high troponin, increased creatine kinase level, elevated triglycerides, high LDH |

| Evidence of COVID-19 infection | Positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by serology, antigen test, or RT-PCR or exposure to patients with COVID-19 infection | RT-PCR, or antigen test, or serology positive for COVID-19 or possible contact with COVID-19 patients within a month before to the initiation of clinical features | SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing may be positive or negative |

| Exclusion of other microbial causes | Exclusion of any other infectious causes of inflammation, including toxic shock syndrome, bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or streptococcal infections | Exclusion of alternative plausible diagnoses | Exclusion of any other microbial cause, including infectious myocarditis, bacterial sepsis, and staphylococcal/streptococcal toxic shock syndromes |

| Additional comments | MIS-C must be considered in children with characteristics of toxic shock syndrome or typical or atypical Kawasaki disease | Consider MIS-C in any pediatric death with evidence of COVID-19 infection. It should be considered in children with features of typical or atypical Kawasaki disease who meet the case definition for MIS-C | Children may fulfill full or partial criteria for Kawasaki disease |

Abbreviations: APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein, echo, echocardiography; CXR, chest X-ray; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GI, gastrointestinal; IL, interleukin; LDH, lactic acid dehydrogenase; MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; 2, RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

4. Clinical Manifestation

The available information regarding the syndrome shows that the age of patients ranged from two months to 20 years, and the majority of cases were previously healthy (15, 16). Almost all affected children had a persistent fever for ≥ 4 days and GI symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomit. Other common clinical manifestations were mucocutaneous changes resembling Kawasaki disease (skin rash and conjunctivitis), extremity edema, lymphadenopathy, headache, mild respiratory distress, myalgia, fatigue, and cardiac symptoms (Table 2). Some patients presented with shock and hypotension requiring PICU admission (17, 18). The cardiac findings in MIS-C patients are divergent from Kawasaki disease’s manifestations. Children with this syndrome were more likely to present with hypotension, shock, and cardiac dysfunction, rather than coronary artery abnormalities (Figure 1) (19).

| Author | Number of Cases | Age, y | Sex | Past Medical History | Ethnicity | Symptoms | Cardiac Involvement | SARS-CoV-2 Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Involvement | Ventricular Function | Arrhythmia/ECG Changes | Troponin | ProBNP/BNP | RT-PCR | Serology | |||||||

| Belhadjer et al. (20) | 35 | 1 - 16 | 18 M, 17 F | Previously healthy (31); asthma (3); SLE (1); overweight (BMI > 25) (6) | - | Fever (35); GI symptoms (29); asthenia (35); respiratory distress (23); rash (20); lymphadenopathy (21); meningism (11); chest pain (6; cardiogenic shock (28); pericardial effusion (3) | Mild coronary dilatation (z score > 2) (6/35); no aneurysms | LVEF < 30% (10); LVEF: 30 to 50% (25); LVEF < 50% (inclusion criteria) (35); takotsubo (1); segmental wall; hypokinesis (3); global LV hypokinesis (31) | Ventricular arrhythmia (1) ST elevation at onset (1) | Elevated (mild to moderate) | Elevated proBNP or BNP (35) | 14 cases were positive | 30/35: IgG+ (28); IgM+ (2) |

| Toubiana et al. (21) | 21 | 4 - 17 | 9 M, 12 F | - | African ancestry (12) | Fever (21); GI symptoms (21); rash (16); conjunctivitis (17); hypotension/shock (17); lips and oral cavity changes (16); changes to extremities (10); serous effusion (12); irritability (12) cervical lymphadenopathy (12); neurological features (6) | Dilated coronary arteries (z-score 2 - 2.5) (5) echo-bright coronary arteries (3) | Myocarditis (16) | Increased QT interval (2) diffuse ST elevation or ventricular dysrhythmias | Elevated (17) | Elevated (14/18) | 8 cases were positive | IgG+ (19) |

| Cheung et al. (22) | 17 | 2 - 16 | 11 M, 4 F | Mild asthma (3) | Ashkenazi; Jewish (6); Black (4); White (6); Asian (1) | Fever (17); skin rash (12); GI symptoms (15); conjunctivitis (11); mucosal changes (9); neurological problems (8); respiratory (7); shock (13); myalgia (5); cervical lymphadenopathy (6); skin desquamation (3) | Echobright coronaries (7) medium-sized aneurysm (z-score 2.5) (1) | Normal-mild LV; dysfunction (11); moderate-severe; LV dysfunction (6) | Non-specific ST/T-wave abnormalities (10) Attenuated QRS voltage (1) | Elevated (14) | Elevated (15) | 8 cases were positive | IgM/IgG + (9) |

| Whittaker et al. (18) | 58 | 6 - 14 | 25 M, 33 F | Comorbid (7): asthma (3); alopecia (1); sickle cell trait (1); epilepsy (1); neuro-disability (1) | White (12); Black (22); Asian (18); other (6) | Fever; GI symptoms; confusion (5); lymphadenopathy (9); skin rash (30); respiratory symptoms (12); conjunctivitis (26); peripheral edema (9); mucosal changes (17); sore throat (6); shock (29) | Dilated coronary arteries (z-score > 2) (8) z-score > 2.5 (7) giant aneurysm (2) | LV dysfunction (18/29) | 4/58: atrial fibrillation (1)1st-degree AV block (1) Second-degree AV block (1) intractable broad complex tachycardia (1) | Elevated | Elevated | 15 cases were positive | IgG+ (40/46) |

| Dolinger et al. (23) | 1 | 14 | M | Crohn disease | - | Persistent fever; GI symptoms; rash; hypotension | - | - | - | - | - | Positive | - |

| Feldstein et al. (17) | 186 | 3 - 12 | 115 M,71 F | Previously healthy (135) 51/186 had an underlying disease other than obesity (autoimmune or immunocompromise (10), respiratory (33), cardiac (5)) BMI-based obesity (45) | White (35); Black (46); Latino or Hispanic (57) | Persistent fever; GI symptoms (171); conjunctivitis (103); skin rash (110); lymphadenopathy (18); peripheral edema (69); respiratory symptoms (131); oral mucosal changes (78); cardiovascular symptoms (149) | Coronary artery aneurysm (z score ≥ 2.5) (15/170) | Myocardial dysfunction (90) | Arrhythmia (12) | Elevated (50/128) | Elevated (73/173) | 73 cases were positive | IgM/IgG+ (85) |

| Dufort et al. (15) | 99 | 0 - 20 | 53 M, 46 F | Pre-existing condition (36/99): 29 of them had obesity | White (29); Black (31); Hispanic (31) | Persistent fever or chills, GI symptoms (79); rash (59); swollen hands or feet (9); hypotension (61); mucosal change (60), neurologic symptoms (30); shock (10); lower respiratory symptoms (40); upper respiratory (27); chest pain (11) | 9 had coronary artery aneurysm (4 z-score > 2.5) | Some degree of ventricular dysfunction (51) myocarditis (52) | - | Elevated (63/89) | Elevated (74/82) | 50 cases were positive | IgG+ (76/77); IgM+ (3/77) |

| Riphagen et al. (24) | 8 | 4 - 14 | 3 F; 5 M | Previously healthy (6); autism (1); alopecia areata and allergic rhinitis (1) | Afro-Caribbean (6) | Persistent fever; GI symptoms (7); myalgia (1); rash (4); odynophagia (3); conjunctivitis (5); headache (2); hypotension/shock (8) | Echobright coronary vessels (8) giant aneurysm (1) | Mild to severe LV dysfunction: 4; BiV dysfunction: 1; RV dysfunction: 1 | 1/8 in context of refractory shock requiring ECMO | Elevated | Elevated | 2 | - |

| Waltuch et al. (25) | 4 | 5 - 13 | 1 F; 3 M | Previously healthy (2); hypothyroidism (1); asthma (1) | - | Persistent fever; GI symptoms; rash (2); myalgia (1); cough (2); conjunctivitis (3); fatigue (2); hypotension | Slight ectasia (1); Dilated coronary arteries (1); mildly dilated coronary artery (1) | Moderately depressed LV function | - | Elevated (1) | Elevated | - | IgG+ (4) |

| Licciardi et al. (26) | 2 | 7, 12 | 2 M | Previously healthy, PFAPA syndrome (1) | - | Persistent fever; rash; GI symptoms; hypotension/shock; Peripheral edema; Conjunctivitis | No | Ventricular dysfunction (2) | - | Elevated (2) | Elevated (1) | Negative | IgM+, IgG+ |

| Borocco et al. (27) | 16 | 5 - 12 | 8 M, 8 F | Previously healthy (10); asthma (2); overweight (4) | - | Persistent fever; GI symptoms (13); mucosal changes (14); rash (13); respiratory symptoms (2); anosmia (1); neurological symptoms (9), shock (11); conjunctivitis (15); lymphadenopathy (6); arthritis (1); pericarditis (4) | Coronary dilation (3) median z score 2.6 | Myocarditis (7); LVEF 35% | - | Elevate (11) | Elevated (11) | 11 cases were positive | IgG+ (7/8) |

| Jones et al. (28) | 1 | 6 months | F | None | - | Persistent fever; mucosal changes; conjunctivitis; peripheral edema; rash; irritability; respiratory symptoms | No | Normal | - | - | - | Positive | - |

| Balasubramanian et al. (29) | 1 | 8 | M | None | Indian | Persistent fever; rash; odynophagia; mild respiratory distress; mucosal changes; conjunctivitis; hypotension; peripheral edema | No | Normal | - | - | - | Positive | - |

| Labe et al. (12) | 2 | 3, 6 | 2 M | None | - | Rash; conjunctivitis; mucosal changes; persistent fever (1); cervical lymphadenopathy | - | - | - | - | - | One case was positive | - |

| Wolfler et al. (16) | 5 | 2 - 168 months | 2 M, 3 F | None | - | Persistent fever; GI symptoms; hypotension/shock (5); conjunctivitis (1); rash (3); respiratory distress (1) | No | Mild-moderate heart dysfunction (5); LVEF < 50% (3) | ST, T waves anomalies, atrial fibrillation (1) | Elevated | Elevated | Positive | - |

| Kaushik et al. (30) | 33 | 6 - 13 | 20 M, 13 F | Previously healthy (17); overweight (4); asthma (5) | Latino or Hispanic (15); Black (13) | Persistent fever; GI symptoms (23); conjunctivitis (12); rash (14); neurologic involvement (4); respiratory symptoms (11); hypotension (21); mucosal changes (7) | Prominent coronary arteries (6) coronary ectasia (2) | LVEF < 50% (21); LVEF < 30% (4) | - | Elevated | Elevated | 11 cases were positive | IgM/IgG+ (27) |

| Greene et al. (31) | 1 | 11 | F | None | - | Persistent fever; rash; GI symptoms; shock; malaise; leg pain; sore throat | No | Decreased LV function | - | Elevated | Elevated | Positive | - |

| Rauf et al. (32) | 1 | 5 | M | None | - | Persistent fever; conjunctivitis; GI symptoms; hypotension; peripheral edema; pyuria | No | Moderate LV dysfunction (FE = 35%) LV global hypokinesia | - | Elevated | Elevated | Negative | - |

| Deza Leon et al. (33) | 1 | 6 | F | None | - | Fever; conjunctivitis; respiratory distress; rash; cardiogenic shock; peripheral edema; odynophagia | No | Mildly diminished; LVEF at onset; severe dysfunction; requiring ECMO | Junctional cardiac rhythm | Elevated | - | Positive | - |

| Chiotos et al. (34) | 6 | 5 - 14 | 1 M, 5 F | None | African-American (2); Caucasian (2) | Persistent fever (6); rash (2); conjunctivitis (2); GI symptoms (5); shock (6); peripheral edema (1); mucosal changes (3); respiratory failure (4); irritability (2); headache (1) | Echobright coronaries (1); diffuse dilation right coronary artery (z-score 3.15) (1) | Mild-Moderate LV dysfunction (4) | - | Elevated (3/5) | Elevated | 3 cases were positive | - |

| Verdoni et al. (35) | 10 | 3 - 16 | 7 M, 3 F | None | Caucasian | Persistent fever; Peripheral edema; hypotension; conjunctivitis; rash; GI symptoms (6); meningeal signs (4); mucosal changes (4) | Coronary aneurysms (> 4 mm) (2) | LVEF < 50% (5) | - | Elevated (5) | Elevated | Two cases were positive | IgM+ (3); IgG+ (8) |

| Blondiaux et al. (36) | 4 | 6 - 12 | 3 F; 1 M | None | - | Persistent fever; conjunctivitis; rash; GI symptoms | No | Transient systolic dysfunction (4) LVEF < 30% (1) | ST depression (1) T waves abnormalities (1) | Elevated | Elevated | Negative | IgG+ (4); IgM+ (1) |

| Ramcharan et al. (37) | 15 | 7 - 11 | 11 M, 4 F | - | African/Afro-Caribbean (6); Asian (6); mixed (2) | Persistent fever (15); GI symptoms (13); lethargy (4); myalgia (4) | Coronary artery abnormalities (14): 1 aneurysm, 6 ectasia, 7 prominent | Reduced LV fractional shortening (8) LVEF < 55% (12) | Abnormal PR interval (9) abnormal T waves | Elevated (15) | Elevated (15) | Two cases were positive | IgM/IgG/IgA+ (12/12) |

| Rivera-Figueroa et al. (13) | 1 | 5 | M | None | African-American | Persistent fever; rash; GI symptoms; shock; conjunctivitis; peripheral edema; mucosal changes | No | Normal | - | Elevated | - | Positive | - |

| Grimaud et al. (38) | 20 | 3 - 15 | 10 M, 10 F | - | - | Fever (20); Abdominal pain (20); rash (10); conjunctivitis (6); mucosal changes (5); lymphadenopathy (2) | No | Cardiogenic/vasoplegic shock (inclusion criteria) (20) | - | Elevated | Elevated | 10 cases were positive | IgG+ (15) |

| Raymond et al. (14) | 1 | 7 | F | None | - | Cough; chest pain; orthopnea; tachycardia; pericarditis | - | - | Low voltage QRS with electrical alternans T-wave inversion in inferior and lateral leads Sinus tachycardia | Not elevated | Elevated | Positive | - |

| Jain et al. (39) | 1 | 3 | M | - | - | Fever; urticarial rashes; diarrhea; facial puffiness conjunctivitis; edema of hands and feet | - | - | Normal | - | - | Positive | - |

| Heidemann et al. (40) | 3 | 5 - 7 | 2 M, 1 F | - | - | Fever; conjunctivitis; dry and cracked lips Rash; cervical lymphadenopathy; GI symptoms; Shock | Dilation of the proximal left arterial descending coronary artery (Z-score: 2.1) and the mean left coronary artery (Z-score: 2.3) seen in one case. Others were normal. | Mildly decreased LV function mild mitral insufficiency (2) | Early repolarization in the lateral precordial leads low voltages in the limb leads Sinus tachycardia PR interval prolongation | Elevated | - | Positive (1) | IgG + (3) |

| Alnashri et al. (41) | 1 | 16 | M | - | - | Fever; diarrhea; vomiting; generalized abdominal pain; pleuritic chest; fissuring of the lower lip; conjunctivitis; bilateral elbow and knee effusion; hypopigmented macular rash on the chest | - | Hypokinesia of inferior wall with an ejection fraction of 45% | Normal | Elevated | - | - | IgG + |

| Torres et al. (42) | 27 | 0 - 14 | 14 M, 13 F | - | - | Fever (27); abdominal pain (17); diarrhea (17); vomiting (13); rash (14); conjunctivitis (13); oral mucosal changes (11); Cough (7); peripheral extremity changes (7) | Coronary artery abnormalities were in one patient | Myocardial dysfunction 4/26 | - | - | - | 14 | 10 |

| Dolhnikoff et al. (43) | 1 | 11 | F | None | African | Cardiovascular shock; persistent fever. odynophagia; myalgia abdominal pain | No | Diffuse LV hypokinesia with decreased LVEF (31%) no segmental wall motion abnormalities | Sinus tachycardia | Elevated | Positive | - | - |

Abbreviations: AV, atrio-ventricular; BiV, biventricular; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ECG, electrocardiogram; F, female; GI, gastrointestinal, IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; M, male; RV, right ventricle; SD, standard deviation; SARS-CoV-2; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

5. COVID-19 Infection

Epidemiological information indicates that SARS-CoV-2 is the possible cause of the syndrome, but the causality is unknown (1). Based on the studies mentioned in Table 2, the positivity percentage of the COVID-19 reverse-transcriptase protein chain reaction (RT-PCR) test varies from 0% to 100%. In most reports, it was positive in less than 50% of cases. On the other hand, the majority of the studies had evidence of positive immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies. These data suggest that a post-infectious disease is more likely to be responsible for this condition than an active infection (44).

6. Cardiac Involvement

6.1. Cardiac Dysfunction

In most cases diagnosed with MIS-C, left ventricular systolic dysfunction has been reported (Table 2). In the first report of MIS-C, Riphagen et al. (24) found ventricular dysfunction in six out of eight cases. The majority of available studies in the literature also reported that ventricular dysfunction happens in up to 50% of MIS-C patients (Table 2). Two case series mentioned cardiac dysfunction as an inclusion criterion (20, 38). Belhadjer et al. (20) considered an acute LV failure (LV ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50%), and Grimaud et al. considered cardiogenic/vasogenic shock as an inclusion criterion (38). The incidence rate of cardiogenic shock is much greater in this syndrome than in the Kawasaki disease (60% vs. 7%) (45). Matsubara et al. (46) found severe LV dysfunction in MIS-C patients. They suggested that the subclinical myocarditis might lead to ventricular dysfunction.

The pathophysiology of cardiac dysfunction in patients with this syndrome is not known. The possible causes of acute myocardial dysfunction following a COVID-19 infection in adults include hypoxic injury, myocarditis, ischemic heart injury due to coronary artery disease, stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo), acute cor pulmonale, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (47-50).

6.2. Laboratory Findings

The elevated troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)/pro-BNP levels have been reported in many patients with MIS-C. In most studies, the elevated BNP and troponin levels have been assessed as biomarkers to diagnose myocardial injury in the absence of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) or myocardial biopsies (15).

6.3. Coronary Involvement

Most reports have mentioned coronary involvement in 0-40% of cases (Table 2) (16, 21, 24, 26, 41). Mild coronary artery dilation with z-scores of 2 - 2.5 has been reported in most cases. However, large coronary artery aneurysm cases have also been mentioned. Some studies found the late development of coronary artery dilation, which necessitates an ongoing follow-up of MIS-C patients.

6.4. ECG Findings

Some case series reported rhythm abnormalities with variable severity in 4% - 58% of patients (Table 2) (18, 22). The most frequently reported arrhythmic manifestations were QTc prolongation, ST-segment changes, and premature atrial or ventricular beats, which all are non-specific. Whittaker et al. (18) reported first- and second-degree atrioventricular blocks, and two other studies mentioned atrial fibrillation (18, 33). Hemodynamic collapse and the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support due to sustained dysrhythmias have also been reported in these patients (18, 24).

6.5. Management

This syndrome is a newly reported condition, and only a few studies have addressed it so far. Our knowledge about it is, therefore, limited, and the treatment of children with MIS has been based on the experts’ advice and the management of Kawasaki disease. Due to the similarity of the symptoms, the treatment method for adults with COVID-19 and other systemic inflammatory diseases can also be used in pediatrics. Management of these children requires a multidisciplinary care team comprising pediatric specialists in cardiology, infectious disease, critical care, and rheumatology.

Generally, the management is decided based on symptoms and their severity. Due to the potential shortage of drug supplies in a pandemic and considering side effects, pharmacotherapy is not recommended for non-hospitalized children. For children who present with mild symptoms, supportive care, including respiratory support and fluid resuscitation, is, therefore, recommended. However, children with hemodynamic instability and severe illness require PICU admission, mostly for inotropic support, which was reported in 20-100% of the cases (15-18, 20-22, 24-27, 30-35, 37, 38). Some of the PICU-admitted children required a veno-arterial (V-A) support (0% - 28%) (15, 17, 18, 20, 24, 30, 33).

Various treatments have been suggested, but their effectiveness is still questionable. Furthermore, these treatments are based on experts’ opinions with no evidence to affirm them.

6.6. Cardiac Support

As mentioned above, a large proportion of children presenting with hemodynamic instability required acute resuscitation. Therefore, it is necessary to follow the pediatric resuscitation guidelines (51). Children suspicious of ventricular dysfunction and cardiogenic shock should receive smaller fluid blouses (e.g., 10 mg/kg), with an evaluation of the signs of fluid overload before each administration.

6.7. Immunomodulatory Therapy

The advantages of using immunomodulatory therapy in the treatment of Kawasaki disease, as well as other systemic inflammatory disorders, are well established (52, 53). An anti-inflammatory therapy, including intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) and corticosteroids, was used in most patients, and a few cases also received an anti-inflammatory dosage of aspirin (15, 16, 18, 20-22, 24, 26, 31, 32, 34-38). It is critical to remember that the administration of IVIG in patients with cardiac dysfunction must be slower to reduce the risk of fluid overload. The dosage of corticosteroids is based on clinical judgment, but in more severe patients, using a low dosage is recommended.

The assessment of the pattern of cytokine storm in patients with MIS-C showed that an important component of this disorder is macrophage activation, as it is also observed in Kawasaki disease and other autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (35, 54). Therefore, corticosteroids are another option in the treatment of MIS-C patients, as they can modulate this condition. However, corticosteroids may cause hypertension that can further exacerbate the underlying cardiac problem (45).

Two treatment protocols with corticosteroids have been proposed. The first method involves an intravenous injection of 0.8 mg/kg methylprednisolone, twice a day for 5 - 7 days or until achieving a normal CRP level and then continuing with oral treatment with 2 mg/kg/day for 2 - 3 weeks. The second protocol includes intravenous methylprednisolone 10 - 30 mg/kg/day for three days, followed by oral prednisone/prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day for four days or until achieving a normal CRP level and then tapering the treatment over 2 - 3 weeks. It is important to know that corticosteroids should not be administered in an active infection phase (1).

In some studies, cytokine blockers have been used as a supplemental therapy, for example, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (e.g., anakinra), interleukin 6 (IL-6) inhibitors (e.g., tocilizumab), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors (e.g., infliximab) (16, 18, 20, 22-25, 27, 29-31, 34). These drugs can be prescribed for children who do not respond to routine treatments.

6.8. Antiplatelet Treatment and Anticoagulation

Hypercoagulable state, blood stasis due to immobilization, possible endothelial injury, and ventricular dysfunction are the proposed reasons for the increased risk of thrombotic complications. As a result, anticoagulant therapy should be considered based on coagulation tests and symptoms (55, 56).

6.9. Antiviral Therapy

The benefits of antiviral therapy, such as remdesivir, for children with this syndrome are still unknown (57, 58). The reports suggest that MIS-C is more likely a post-infectious complication in children rather than an active infection. Nonetheless, antiviral drugs could be considered in patients with a positive RT-PCR test, after consulting an infectious disease specialist.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, children seem to proceed better with the novel coronavirus infection than adults. On the other hand, some children show signs and symptoms of MIS-C, which is a severe complication of the disease. Pediatricians should be aware of this syndrome and differentiate it from other differential diagnoses, including the Kawasaki disease. These children can quickly deteriorate and should closely be observed. The etiology of MIS-C is not yet fully understood, and treatment is mostly based on experts’ opinions. More studies are, therefore, required to define evidence-based management for this new syndrome, and our study played a part in this literature contribution.