1. Background

Pneumonia, especially community-acquired pneumonia, is one of the leading causes of death among children, especially those under the age of 5 years, leading to more than one million deaths each year worldwide (1, 2). In the United States alone, there are approximately 2.5 to 3.3 million episodes of pediatric pneumonia, with more than 200,000 hospitalizations per year (3, 4). In children with abnormal immune systems, pneumonia can be caused by a variety of microbial strains such as viruses, bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae or atypical bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae), Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and even fungi such as Histoplasma (5, 6). Viral infections account for more than 80% of pneumonic episodes in children under 2 years of age and 49% of pneumonia in older children (7). The viral etiologies of children predisposed to pneumonia vary based on the patients' geographical, seasonal, and age characteristics. However, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human rhinovirus (HRV), influenza, and parainfluenza viruses are the most common viruses related to children with pneumonia (8, 9). Viral infections in children with underlying diseases or some types of bacterial infections can become serious. Numerous cases of RSV-induced bronchiolitis with an underlying bacterial infection requiring mechanical ventilation treatment have also been reported (10, 11). On the other hand, the occurrence of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic after a cluster of pneumonia cases was reported in Wuhan City, China, especially with new mutant strains, has been associated with significant involvement of the pediatric respiratory system and, based on the available evidence, has also led to morbidity and mortality in children (12-15). There is even evidence of an urgent need for vaccination against COVID-19 pneumonia in children, even at a young age (16). Determining the frequency of respiratory viral infections during the COVID-19 pandemic can be important for epidemiology information. On the other hand, comparing these results with those before COVID-19 in the future may help researchers understand COVID-19's pathogenesis and its competition with other RNA respiratory viruses.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate and predict the occurrence of common respiratory viral infections among children hospitalized with a pneumonia diagnosis. This study aimed to detect the prevalence of viral infections caused by 17 different types of respiratory viruses in children with viral respiratory symptoms admitted to a pediatric referral hospital in Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

This cross-sectional study collected 87 nasopharyngeal specimens from 87 children hospitalized in different wards of Mofid Children's Hospital with respiratory symptoms from September 2021 to February 2022. The inclusion criteria were children who presented with signs and symptoms of upper and/or lower respiratory tract infection requiring hospitalization. Written consent was obtained from the parents of all children before entering the study. The attending pediatrician diagnosed each affected child based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for children's respiratory infections (17). The baseline characteristics include demographics, medical history, and clinical manifestations on admission. The ethical code of this study is IR.SBMU.RICH.REC.1401.003 at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3.2. Virus Detection Protocols

The nasopharyngeal swabs were collected for each patient under strict infection control guidance using rayon-budded swabs for respiratory virus with the educated hospital staff, and the specimens transfer to molecular by laboratory virus transport media (VTM). The RdRp and N viral genes were detected by real-time multiplex PCR (RT-PCR), and RNase-p was used as an internal control. After preparing the specimens, total RNA was extracted from the nasopharyngeal samples using the Behprep viral RNA extraction kit (BehGene. Cat. No. BPVD050).

The Genova cat. No. GA-17HiTeq-32 one-step multiplex Real-Time PCR was used to simultaneously determine and identify 17 different respiratory viruses. The viral panel profile was:

COVID-19, influenza A virus, influenza B virus, RSV, parainfluenza 1, 2 and 3, Human Bocavirus 1, 2, 3, influenza H1N1, HCOV229E virus, HCOV-NL63, HCOV-OC43, HCOV-HKU1, human metapneumovirus, and adenovirus. In this kit, the human RNase P gene is also used as an internal control.

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were children who presented with signs and symptoms of upper and/or lower respiratory tract infection requiring hospitalization.

3.4. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were children who presented without signs and symptoms of upper and/or lower respiratory tract infection requiring hospitalization or were suspicious of bacterial infection according to symptoms and laboratory CBC blood test.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and were summarized by frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare the categorical variables. P values of ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For statistical analysis, the statistical software SPSS version 23.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York) was used.

4. Results

In total, 87 children with the definitive diagnosis of viral respiratory disorders were assessed with respect to the clinical manifestations as well as viral strains leading to respiratory disorders. The average age of subjects was 4.68 ± 4.24 years (ranged 2 months to 16 years), and 70.1% were male. Regarding clinical manifestations (Table 1), the most common respiratory symptoms were cough revealed in 82.8%, followed by respiratory distress in 13.8%, and tachypnea in 6.9%. The respiratory virus was detected in 29 (31%) of cases.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 4.68 ± 4.24 |

| Age subgroups (y) | |

| < 2 | 26 (29.9) |

| 2 to 6 | 36 (41.4) |

| 7 to 10 | 13 (14.9) |

| > 10 | 12 (13.8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 61 (70.1) |

| Female | 26 (29.9) |

| Clinical manifestations | |

| Dyspnea | 5 (5.7) |

| Cough | 72 (82.8) |

| Respiratory distress | 12 (13.8) |

| Grunting | 1 (1.1) |

| Tachypnea | 6 (6.9) |

| Reduced arterial O2 saturation | 3 (3.4) |

| Runny nose | 7 (8.0) |

| Coryza | 1 (1.1) |

| Chest wall retractions | 1 (1.1) |

| Sneezing | 2 (2.3) |

| Wheezing | 4 (4.6) |

| Hoarseness | 1 (1.1) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

The assessment of viral strains using the multiplex real-time PCR technique revealed a 29 (33.3%) positive rate of detecting the different respiratory viruses. The Coronavirus (COVID-19) in 14 (16.1%), Influenza A virus in 5 (5.7%) (Table 2). The co-infection of COVID-19 with parainfluenza was observed in one case, and the respiratory symptoms, in this case, were not different from other COVID-19-infected patients. Interestingly, in 69% of cases, no viral strain associated with pediatric respiratory disease was detected.

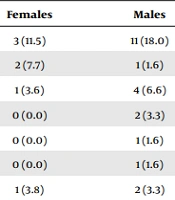

| Type of Virus | Total | Females | Males | P Value (Chi-Square Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronavirus (COVID-19) | 14 (16.1) | 3 (11.5) | 11 (18.0) | 0.540 |

| Metapneumovirus | 3 (3.4) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (1.6) | 0.212 |

| Influenza A virus | 5 (5.7) | 1 (3.6) | 4 (6.6) | 0.619 |

| RSV | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 0.350 |

| Bocavirus | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0.999 |

| HCOV nl63 | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0.999 |

| Parainfluenza | 3 (3.4) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (3.3) | 0.894 |

| Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Parainfluenza | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0.999 |

Abbreviation: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Comparing different types of viral strains in male and female genders (Table 2) showed no significant difference (P value ≥ 0.05) in the prevalence rate of viral types between the two genders. In this regard, the RT-PCR negativity in male and female children was 67.2% and 73.1%, respectively (P = 0.611). As shown in Table 3, the prevalence rate of different viral respiratory strains was independent of patients’ age (P value ≥ 0.05). The average age of patients with none, one strain, and two strains of respiratory viruses was 4.56 ± 3.78 years, 5.28 ± 5.25 years, and 0.75 ± 0.35 years respectively, indicating no association of age with the rate of respiratory viral strains.

| Type of Virus | < 2 y | 2 to 6 y | 7 to 10 y | > 10 y | P Value (Chi-Square Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronavirus (COVID-19) | 5 (19.2) | 5 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (33.3) | 0.141 |

| Metapneumovirus | 1 (3.8) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.755 |

| Influenza A virus | 1 (3.8) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0.307 |

| RSV | 1 (3.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.825 |

| Bocavirus | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.499 |

| HCOV nl63 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.124 |

| Parainfluenza | 2 (7.7) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.503 |

Abbreviation: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

While mild symptoms of COVID-19 infections are observed in children, their role in the pandemic should not be ignored (18). The present study had several significant findings compared to other studies. First, we did not find any etiologic cases in a significant proportion of children with clinical symptoms in the assessment of viral etiology, and in fact, it appears that the onset of these clinical manifestations is due to respiratory involvement from other strains such as bacterial or even fungal strains. In our study, no viral strain was associated with pediatric respiratory disease in 69% of symptomatic children. This rate widely varied in different reports. In a similar study by Sarna et al. in 2018 on Australasian children (19), 32.7% of children remained virus-positive, which was close to our report. In another survey by Snoeck et al. in 2021 in Lao PDR (20), by RT-PCR screening, at least one pathogen could be identified for 71.7% of cases. Rieple et al. reported 26.7% RSV and 7.2% metapneumovirus in children with acute respiratory Austria in 2023 (21). The frequency of these viral is more than the results of the current study, and it can be because of the lower frequency of COVID-19 in Austria compared to Iran. The less frequency of COVID-19 provided the conditions for more abundance of other respiratory viruses. Calvo et al. (22) study on Spanish children with respiratory infections, 79% of affected infants had at least one positive respiratory viral infection. Various factors are involved in the reported rate of viral strains causing viral respiratory infections in hospitalized children, including the age range for study, the means of tracking viral strains, the geographic difference and underlying disease, and even the social and demographic characteristics of that community.

As the second point, common viral strains caused respiratory infections in 29 (33.3%) of specimens. The most common strains detected included the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in 16.1%, influenza A virus in 5.7%, metapneumovirus in 3.4%, parainfluenza in 3.4%, RSV in 2.3% and rarely bocavirus in 1.1% and HCOV nl63 in 1.1% of children. In other words, first, it is quite obvious that the period the COVID-19 pandemic and special attention to the detection of this type of infection in children hospitalized is the most detected coronavirus strain. In the report by Calvo et al. (22), the virus identified most frequently was rhinovirus (82%), followed by adenovirus (9.7%), parainfluenza virus (4.2%), human bocavirus (3.2%), metapneumovirus (2.9%), influenza (2.2%) and RSV (1.6%). In Wang et al. study in China (23), the predominant viruses were RSV at 68.1%, followed by adenovirus at 16.0% and parainfluenza at 11.0%.

The types of detected viruses in the different studies can be associated with the season, geographical differences, underlying diseases, ward of hospitalization, and infection control measures. Also, even though in our study, the gender or age of patients did not play a significant role in the prevalence of viral strains associated with childhood respiratory diseases, in some reports, significant differences in the prevalence of these strains were reported between the two sexes, at different ages and even in different seasons. As shown by Zhu et al. in 2021 (24), first, the adenovirus positivity rate was highest in the age range 3 to 6 years, while the influenza A and B positivity rates were highest in the ages higher than 6 years, and the RSV positivity rate was highest in children younger than 1 year, and thus there was a significant difference in the positivity rate of viral infection among different ages. They also showed that the rate of positive viral infection was highest in winter. Therefore, it can be said with certainty that the results related to the type and distribution of sex or age and viral strains associated with respiratory infections in children from one community cannot be generalized to other communities, and therefore the management approach to these infections will be logically unique to that community.

Based on our findings, COVID-19 co-infection with parainfluenza was observed in a hospitalized patient. This case will be important in various ways. From the first months of the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, coinciding SARS‐CoV‐2 with the seasonal influenza virus outbreak was described (25). Based on subsequent studies, it was found that the coexistence of these two types of infection can be associated with the intensification of inflammatory responses caused by viral infections and, therefore, a worse prognosis of COVID-19 disease. As Xia et al. (26) indicated, higher serum procalcitonin levels in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 concurrently with other common respiratory infections justify the intensification of inflammatory responses. These responses will be more severe in patients with immunocompromised immune systems (27). According to the literature, such poor events have been more evident, especially in children under 3 years suffering from COVID-19 coinfected with RSV and human metapneumovirus (28). It is considered that the common respiratory viral infections in children had low frequency in our study because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This change in the prevalence of respiratory viral infections like influenza A/B virus before and after of COVID-19 pandemic was observed clearly in Lai et al. study in Chine in 2022 (29). In Letafati et al. study in Iran, Also RSV was not detected in children with acute respiratory infections during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran (30). The results of this study are similar to ours.

Therefore, in our study, the coexistence of COVID-19 with other viral infections was observed in children; it can indicate the fact that the management and treatment approaches of these patients can be different from other COVID-19 patients.

5.1. Limitations of This Study

The low number of specimens because of the cost of the multiplex real-time PCR kit is the limitation of this study.

5.2. Conclusions

The rate of viral infections was independent of the sex or age of children, according to the results of this study. Other viruses besides COVID-19, such as Influenza A virus and parainfluenza detected in children with respiratory symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the identification of other respiratory viruses in children with symptoms of acute respiratory infections during the covid pandemic, the frequency of these types of viruses has decreased in the pandemic compared to before the pandemic.