1. Background

Central nervous system (CNS) infections refer to infections and inflammation of the brain, with a higher prevalence observed in pediatric populations (1-3). Children can experience a wide range of outcomes, from rapid recovery to severe dysfunction, depending on various risk factors (4, 5). Previous studies have shown a higher prevalence of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with CNS infections, including those who have fully recovered (6, 7). Risk factors for long-term neurological complications include focal neurological defects, abnormal neuroimaging, infectious causes, and prolonged hospitalization (8). Children with CNS infections often require regular neuropsychological assessments, and rehabilitation services may be necessary for those with neuropsychological complications (3). However, there is limited understanding of the factors influencing outcomes in pediatric patients with CNS infections, making it difficult to accurately predict patient outcomes (9, 10).

In addition to traditional medical outcome measures such as mortality, the concept of quality of life has gained significant importance, especially in pediatric populations (11, 12). Quality of life encompasses physical, emotional, and social aspects and serves as a key indicator of outcomes in children (13). The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales (PedsQL) is a standardized questionnaire used to assess quality of life in children, evaluating domains such as physical, emotional, social, and school functioning. Low PedsQL scores can indicate challenges such as depression, fatigue, decreased school attendance, and social pressures, which are critical when assessing the long-term effects of CNS infections (11).

2. Objectives

In this study, we examined the prevalence of ADHD and quality of life in pediatric patients with CNS infections admitted to the largest referral hospital and the main children's hospital in Isfahan, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

In this prospective longitudinal study, we analyzed medical records and clinical evaluation reports of patients suspected of having CNS infections, admitted to referral hospitals affiliated with Isfahan University of Medical Sciences between 2019 and 2020. The study focused on infants presenting with fever and seizures, children with fever and suspicious CNS symptoms, positive meningeal signs, and acute loss of consciousness. The inclusion criteria involved patients aged 6 to 16 years without underlying conditions such as endocrinopathies, metabolic disorders, genetic disorders, or previous nervous system conditions. We excluded patients with incomplete clinical, laboratory, and imaging data, as well as those diagnosed with non-infectious causes like autoimmune encephalitis. Additionally, patients who declined to participate or withdrew from the study were also excluded.

The diagnosis of CNS infection was confirmed by pediatric infectious disease and pediatric neurology experts (H.R., Z.P., O.Y.) after a thorough review of medical records and data. Initially, 108 patients were suspected of having a CNS infection, but 14 were excluded due to underlying conditions. Therefore, a total of 94 patients were included in the final analysis. Demographic information, clinical features, and laboratory data were collected anonymously using a research team-designed form. All eligible patients participated in the study after being informed about its objectives, and parental consent was obtained to ensure the confidentiality of their information. The study protocol received ethical approval from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences' ethics committee (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.344).

3.2. Study Procedure

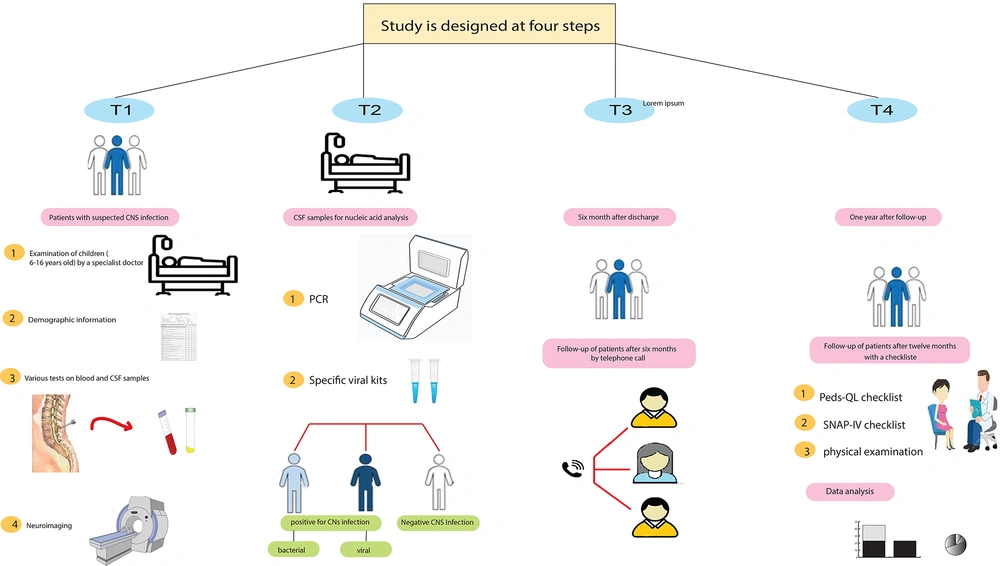

The study was conducted in four steps (Figure 1).

T1: Upon the patient's admission, an initial assessment was conducted to gather demographic information and obtain their medical history. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, laboratory data, and neuroimaging were obtained.

T2: During hospitalization, CSF samples were collected for nucleic acid analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the SinaPure ONE kit (SinaClon Co., Iran) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Based on laboratory results and medical records, patients were categorized into three groups: Bacterial infection, viral infection, and negative infection. Patients with CNS symptoms but no evidence of infection were classified as negative.

T3: Six months after being discharged from the hospital, patients were contacted through phone calls, and data collection forms were filled out regarding their current condition and well-being.

T4: One year after discharge, patients underwent a comprehensive examination. The SNAP-IV checklist was used for ADHD diagnosis, and the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scale (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™) was used to measure health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients. The maximum age on the checklist was adjusted to 15 years old to match the inclusion criteria (6 - 16 years old). Data from the study groups, including self-assessment checklists, PedsQL scores, and ADHD scores from the final clinic visit, were analyzed to compare ADHD symptom presentation among the groups. Parental participation was sought to complete the required items in the data collection forms.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25.0, IBM Corp.) was used for the data analysis. Qualitative variables were presented as percentages, and quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The chi-square test was employed for categorical variables, while the Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association of positive ADHD, higher PedsQL scores, seizures, and abnormal neurological exams between the CNS infection-positive and CNS infection-negative groups. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Clinical Features and Characteristics of Patients

The study included 94 children with a mean age of 13.29 ± 6.73 years (ranging from 6 to 16 years old). Among the participants, 42.6% were female and 57.4% were male. Fever was the most common presenting complaint in their medical history. Of all cases, 91 patients (96.8%) were discharged without neurological complications, while 3 patients (3.2%) died during hospitalization. Patients were categorized into three groups: Bacterial infection (11 patients, 11.7%), viral infection (37 patients, 39.4%), and negative for CNS infection (46 patients, 48.9%). Sixteen patients (17%) required admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). Additional clinical features and patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| Variables | Total (n = 94) | Positive CNS Infection | Negative CNS Infection (n = 46) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial (n = 11) | Viral (n = 37) | ||||

| (A) Patients’ characteristics | |||||

| Gender | 0.49 | ||||

| Male | 54 (57.4) | 5 (45.5) | 20 (54.0) | 29 (63.0) | |

| Feeding in the first-year | 0.87 | ||||

| Breastfeeding | 72 (76.6) | 9 (81.8) | 29 (78.4) | 34 (74.0) | |

| Formula | 5 (5.3) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Both | 17 (18.1) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (16.2) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Attending school | 17 (18.1) | 1 (9.1) | 9 (24.3) | 7 (15.2) | 0.41 |

| Exposed to sick person | 10 (10.6) | 0 | 9 (24.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0.03 b |

| Secondhand smoke | 18 (19.1) | 3 (27.3) | 11 (29.7) | 4 (8.7) | 0.38 |

| Maternal education | 0.34 | ||||

| Illiterate | 9 (9.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (13.5) | 4 (8.7) | |

| School | 56 (59.6) | 7 (63.6) | 22 (59.5) | 27 (58.7) | |

| University | 29 (30.8) | 4 (36.4) | 10 (27.0) | 15 (32.6) | |

| (B) Signs of patients | |||||

| Tachy/bradycardia | 36 (38.3) | 4 (36.4) | 18 (48.6) | 14 (30.4) | 0.23 |

| Tachy/bradypnea | 36 (38.3) | 5 (45.5) | 16 (43.24) | 15 (32.6) | 0.51 |

| CRT > 2 Seconds | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.2) | 0.86 |

| Hypoxia | 14 (14.9) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (13.5) | 6 (13.0) | 0.54 |

| Neck rigidity, Kernig, Brudzinski | 25 (26.6) | 6 | 12 | 7 | 0.13 |

| Weakness, fatigue | 8 (8.5) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0.08 |

| Skin rash | 22 (23.4) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (16.2) | 14 (30.4) | 0.28 |

| Respiratory tract infection signs | 12 (12.76) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (10.9) | 0.77 |

The Clinical Features and Characteristic of Patients in Different Groups a

4.2. Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

Significant differences were observed between the CNS infection-positive and CNS infection-negative groups regarding white blood cell (WBC) count in blood analysis (P = 0.008). In the CSF analysis, significant differences were found between the groups in terms of WBC count, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), lymphocytes, protein, and glucose levels (P < 0.05). Detailed results of the blood and CSF analyses are presented in Table 2.

| Variables | Total (n = 94) | Positive CNS Infection | Negative CNS Infection (n = 46) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial (n = 11) | Viral (n = 37) | ||||

| (A) Blood analysis | |||||

| WBC | 11391 ± 5635 | 16936 ± 6753 | 10480 ± 4793 | 10778 ± 5324 | 0.008 b |

| PMN | 53.98 | 59.63 | 51.44 | 54.63 | 0.520 |

| Lymphocytes | 37.43 | 30.81 | 39.69 | 37.25 | 0.442 |

| Platelets | 324944 ± 148461 | 352818 ± 83537 | 326200 ± 143183 | 317323 ± 165167 | 0.541 |

| ESR | 31.83 ± 26.50 | 49.00 ± 36.48 | 30.62 ± 24.94 | 28.65 ± 23.90 | 0.147 |

| (B) CSF analysis | |||||

| WBC | 164 ± 688 | 1168 ± 1754 | 66 ± 133 | 2.5 ± 8.5 | < 0.001 b |

| PMN | 25 | 71 | 25 | 15 | < 0.001 b |

| Lymphocytes | 20 | 28 | 34 | 6.4 | < 0.001 b |

| Protein | 40.30 ± 53.14 | 89.00 ± 58.48 | 50.90 ± 65.09 | 19.21 ± 23.04 | < 0.001 b |

| Glucose | 54.61 ± 17.62 | 39.00 ± 21.21 | 54.33 ± 18.18 | 58.56 ± 14.21 | 0.01 b |

Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis of Patients in Different Groups a

4.3. Molecular Analysis

Molecular analysis revealed that Enterovirus (43.2%), Herpes simplex virus (27.0%), and gram-positive cocci (45.5%) were the most frequently detected microorganisms in patients with positive CNS infection (Table 3).

| Viral Types | Frequency (n = 37) | Bacterial Types | Frequency (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterovirus | 16 (43.2) | Gram-negative cocci | 2 (18.1) |

| Herpes simplex virus | 10 (27.0) | Gram-positive cocci | 5 (45.5) |

| Mumps | 2 (5.4) | Burkholderia | 1 (9.1) |

| Varicella zoster virus | 3 (8.1) | Salmonella typhi | 1 (9.1) |

| Epstein–Barr virus | 6 (16.2) | Brucellosis | 1 (9.1) |

| Adenovirus | 0 | Citrobacter | 1 (9.1) |

| Influenza viruses | 0 | - | - |

The Frequency of Detected Viruses and Bacteria by Molecular Analysis a

4.4. Imaging Studies

Neuroimaging was performed on 84 out of the 94 subjects, with abnormal results found in 21 cases. Of these, 36.4% were in the bacterial group, and 45.9% were in the viral group, showing a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001).

4.5. Patient Monitoring

Significant differences were observed between the CNS infection-positive and CNS infection-negative groups regarding the PedsQL total score and abnormal neurological examination (P < 0.05). Additionally, bacterial and viral infections showed significant differences in terms of both PedsQL total score and abnormal neurological examination (P < 0.05). After one year of follow-up, 30 patients were diagnosed with ADHD, and 35 patients experienced seizures (Table 4). The PedsQL score was significantly associated with positive CNS infection (P = 0.014; OR = 1.270; 95% CI = 1.050 - 1.534), and abnormal neurological examination was also significantly associated with positive CNS infection (P = 0.012; OR = 3.799; 95% CI = 1.345 - 10.729) (Table 4).

| Variables | Positive CNS Infection | Negative CNS Infection (n = 46) | P–Value b | P–Value c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial (n = 11) | Viral (n = 37) | |||||

| (A) Comparison Analysis | ||||||

| PedsQL total | 16.54 ± 21.54 | 22.48 ± 21.98 | 11.82 ± 15.94 | 0.047 d | 0.020 d | |

| ADHD positive | 5 (45.5) | 12 (32.4) | 13 (28) | 0.553 | 0.251 | |

| Abnormal neurological examination | 2 (18.2) | 15 (40.5) | 7 (15.2) | 0.028 d | 0.033 d | |

| Seizure | 4 (36.4) | 18 (48.6) | 13 (28.3) | 0.161 | 0.077 | |

| Abnormal imaging | 4 (36.4) | 17 (45.9) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 d | < 0.001 d | |

| (B) Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis | ||||||

| Variables and Group | OR | CI | P-Value | |||

| ADHD positive | ||||||

| Negative CNS (ref) | 1 | - | - | |||

| Viral | 1.066 | 0.865 - 1.313 | 0.547 | |||

| Bacterial | 1.180 | 0.867 - 1.607 | 0.293 | |||

| Positive CNS | 1.093 | 0.900 - 1.327 | 0.369 | |||

| PedsQL (upper 25th percentile) | ||||||

| Negative CNS (ref) | 1 | - | - | |||

| Viral | 1.270 | 1.050 - 1.534 | 0.014 d | |||

| Bacterial | 1.270 | 0.928 - 1.737 | 0.136 | |||

| Positive CNS | 3.800 | 1.300 - 11.110 | 0.015 d | |||

| Seizure | ||||||

| Negative CNS (ref) | 1 | - | - | |||

| Viral | 2.405 | 0.968 - 5.972 | 0.059 | |||

| Bacterial | 1.451 | 0.363 - 5.801 | 0.599 | |||

| Positive CNS | 1.148 | 0.912 - 5.060 | 0.080 | |||

| Abnormal neurological examination | ||||||

| Negative CNS (ref) | 1 | - | - | |||

| Viral | 3.799 | 1.345 - 10.729 | 0.012 d | |||

| Bacterial | 1.238 | 0.219 - 6.988 | 0.809 | |||

| Positive CNS | 3.055 | 1.126 - 8.293 | 0.028 | |||

The Monitoring of Patients in Different Groups for One Year a

5. Discussion

The present study contributes to the existing body of research on CNS infections in pediatrics by emphasizing their association with complications such as mental disabilities and difficulties in learning and school activities. Our findings show a significant decline in the quality of life among patients with CNS infections, aligning with previous studies that have also reported reduced quality of life in pediatric patients suffering from inflammatory brain diseases (11). For instance, Liu et al. identified a statistically significant correlation between seizures or cognitive dysfunction at presentation and diminished quality of life in children with inflammatory brain illnesses (14). Similarly, Rao et al. reported significantly lower PedsQL scores in children diagnosed with acute encephalitis (15). Gigi et al. also demonstrated that children with post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus had lower PedsQL scores compared to their healthy counterparts (16).

Moreover, ADHD has been reported with increased frequency among patients with CNS infections. International studies have highlighted a significantly higher prevalence of ADHD (50%) and learning disabilities (20%) in children with CNS infections, such as encephalitis, compared to the general population, where rates of ADHD range from 5 - 10% (17, 18). In our study, 30 patients (31.9%) out of the 94 hospitalized children exhibited ADHD symptoms within the year following hospitalization. Although ADHD can be identified in patients with brain infections after six years of follow-up, our study's relatively small sample size is due to its short-term, one-year follow-up (17).

An important factor in understanding the clinical outcomes of different types of CNS infections, such as encephalitis, is recognizing the specific infectious agents and prognostic factors present in patients (15). In a study by Salih et al., the outcomes of 18 patients with herpes simplex encephalitis were examined over 13 years. The study found that 39% of the patients experienced moderate to severe sequelae, while 61% had either no sequelae or only minor ones (19). In the present study, abnormal neurological examination findings were observed in 25.5% (24 cases) of the patients after one year, with 8.4% in the bacterial group, 40.5% in the viral group, and 15.2% in the negative CNS infection group. Patients with positive CNS infections had a higher frequency of abnormal neurological examination findings compared to those with negative CNS infections.

Rao et al. conducted a study on 142 patients over 10 years and found that the presence of seizures at admission was associated with ongoing seizure disorders during follow-up. Additionally, abnormal MRI findings and the number of abnormalities at initial presentation were linked to lower quality-of-life scores (15, 20). In our study, 35 out of 94 patients experienced seizures, with rates of 36.4% in the bacterial group, 48.6% in the viral group, and 28.3% in the negative CNS infection group.

Neuroimaging was performed on 84 subjects, revealing abnormal findings in 21 cases. Among these, 80.1% were in the bacterial group, while 19% were in the viral group. The difference between patients with positive and negative CNS infections was statistically significant. Early diagnosis and treatment initiation are crucial, as delayed treatment increases the risk of severe complications. Empirical treatment with acyclovir is recommended if viral encephalitis cannot be ruled out within six hours of admission (20). Focal cortical parenchymal abnormalities observed on MRI have also been shown to predict poorer long-term neurological outcomes (21).

While our study suggests that CNS infections lead to a decrease in the quality of life among pediatric patients, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The small sample size and short follow-up period are critical.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study revealed that children hospitalized due to CNS infections require early diagnosis and timely, comprehensive treatment. Additionally, a higher incidence of mental function impairments was observed in children one year after the onset of the disease. These patients exhibited lower PedsQL scores, indicating a reduced quality of life. It is essential that all patients with encephalitis undergo long-term follow-up evaluations, and neuropsychological rehabilitation should be provided for these individuals. Further research in this area is necessary to enhance knowledge and potentially improve patient care and outcomes.