1. Background

Emergency room consultations are greatly needed to manage lower respiratory tract infections such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia among sick children (1). Pediatric pneumonia is the leading cause of death and morbidity in hospitalized children under 5 years old. Viral agents are the most frequent organisms causing pneumonia in children between 2 and 5 years of age. Most deaths associated with this disease are reported in developing countries; however, the health costs in the developed world are considerable (2). Viruses are most commonly responsible for community-associated pneumonia (CAP) in hospitalized children. Fever, anorexia, tachypnea, and cough are frequent presentations in these cases (3). Bronchiolitis is defined as inflammation followed by obstruction in the lower respiratory tract, almost always originating from a viral etiology in infants (4). Human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) is the most common infection causing bronchiolitis, while other viruses such as human metapneumovirus (hMPV) and human rhinovirus (hRV) are less frequent (5). Additionally, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, bocavirus, adenovirus, and coronavirus can also lead to viral CAP (6).

In a 3-month prospective multicenter study in Madrid, Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic, 33 children with acute bronchiolitis were enrolled and tested for viral pathogens using the multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. They found that 28 of their cases were infected with rhinoviruses, while the others were infected with COVID-19 (7). Another analysis of three separate datasets from New South Wales, Australia concluded that despite doubled rates of testing in 2020, the frequency of hRSV decreased by about 90% compared with average detection in similar months from 2013 to 2019 (8). Similar measures were reported for the influenza virus by the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with the number of infected and deceased individuals decreasing by about 96.6% and 90.3%, respectively (9).

Although previous studies have been conducted worldwide to investigate the viral causes of lower respiratory infections before the pandemic, the increase in respiratory infections following the coronavirus pandemic shifted researchers' focus to this virus. However, it became evident that other viruses should also be monitored.

2. Objectives

We designed this study with two goals: First, to identify viral agents causing lower respiratory infections such as pneumonia and bronchiolitis in children during the COVID-19 pandemic, and second, to evaluate the rate of simultaneous infection with two or more viruses in children. Given the diverse unknown aspects of this emerging virus and the potential changes in the epidemiology of respiratory infections, there was a need to assess the current situation at a referral general children's hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic and determine which viruses are responsible for lower respiratory tract infections, including pneumonia and bronchiolitis. Moreover, we aimed to identify which viruses might coinfect with COVID-19 in Mashhad.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Patients’ Recruitment

This study employed a descriptive and analytic cross-sectional method to analyze hospitalized children diagnosed with bronchiolitis and pneumonia at Akbar Hospital, Mashhad, Iran, over one year from January 20, 2021, to January 20, 2022, immediately after preparing the detection kit. Pediatric infectious disease subspecialists or general pediatricians made diagnoses according to the latest criteria mentioned in the 21st edition of the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Patients with tachypnea, fever, and apparent abnormalities in chest x-rays, and neonates with the first episode of wheezing attacks following upper respiratory tract infection symptoms, were diagnosed with pneumonia and bronchiolitis, respectively.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: Underlying cardiopulmonary or neurologic disease or airway anomalies; childbirth at a gestational age of less than 37 weeks and with a birth weight of less than 2.5 kg; concurrent otitis, sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, immunodeficiency, severe malnutrition, and hospital-acquired bronchiolitis and pneumonia.

3.2. Sampling

The convenience sampling method was used to gather all eligible hospitalized children older than 2 months and younger than 14 years.

3.3. Data Collection

The research team designed and used a checklist to collect demographic, clinical, and paraclinical information of patients, including their past medical history, need for intubation or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during hospitalization, and their outcomes. Admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and length of stay in the hospital were also recorded. Nasopharyngeal smears were taken from all patients, and the agents responsible for infection were detected using the Multiplex PCR method (AmpliSens ARVI-Screen-FRT, Russia). A RIBO-prep nucleic acid extraction kit (AmpliSens, Russia) was used. The samples were checked for the following viral agents: Influenza virus, Parainfluenza virus, Coronaviruses [E229, OC43, HKU1, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)], Rhinovirus, Metapneumovirus, Adenovirus, Human bocavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or guardians of the children. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, with the following approval code:IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1399.767.

3.5. Statistical Analyzes

Data were reported using descriptive statistics and analyzed with IBM SPSS software, version 26, Armonk, New York, United States. The normality of quantitative data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Qualitative data were analyzed using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. For quantitative data with a normal distribution, independent sample t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used. The significance level was set at less than 0.05.

4. Results

In this study, 102 hospitalized children met the inclusion criteria. Among them, 97 children had pneumonia and the remaining were affected by bronchiolitis. Their baseline characteristics and clinical data are presented in Table 1. Age was significantly lower in patients with bronchiolitis (0.16 ± 0.14 years) compared to those diagnosed with pneumonia (3.99 ± 3.38 years). Cough was the most common on-admission presentation in both groups (> 90%), followed by fever in pneumonia patients and wheezing in the bronchiolitis group. The respiratory and pulse rates of bronchiolitis cases were also considerably higher (P < 0.05).

| Variables | All N= 102 (100.0%) | Pneumonia Patients. N = 97 (95.1%) | Bronchiolitis Patients. N = 5 (4.9%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 3.80 ± 3.40 | 3.99 ± 3.38 | 0.16 ± 0.14 | < 0.001 b |

| Gender | 0.646 c | |||

| Male | 60 (58.8) | 56 (57.7) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Female | 42 (41.2) | 41 (42.3) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Underlying diseases (+) | 32 (31.4) | 32 (33.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of admission to ICU# (+) | 12 (11.8) | 12 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of medicines (+) | 12 (11.8) | 12 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| On admission signs, symptoms, and paraclinical findings | ||||

| Rhinorrhea | 17 (16.7) | 17 (17.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Fever | 73 (71.6) | 71 (73.2) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Cough | 93 (91.2) | 88 (90.7) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Conjunctivitis | 6 (5.9) | 6 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pharyngitis | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Whizzing | 8 (7.9) | 4 (4.2) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Crackle | 37 (36.3) | 35 (36.1) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Respiratory rate | 33.73 ± 11.87 | 32.94 ± 11.28 | 49.00 ± 13.93 | 0.003 b |

| Pulse rate - | 124.96 ± 14.71 | 124.21 ± 14.58 | 139.6 ± 9.3 | 0.022 b |

| Temperature | 38.14 ± 0.78 | 38.16 ± 0.78 | 37.70 ± 0.64 | 0.199 b |

| O2 saturation | 93.64 ± 3.40 | 93.62 ± 3.48 | 94.00 ± 1.23 | 0.808 b |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

bAnalysis of variance.

cFisher’s exact test.

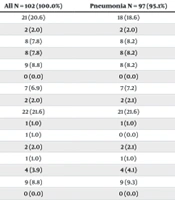

The frequency of all viruses examined in these assessments is reported in Table 2. Results of PCR analyses revealed that 25.4% of cases presented to the emergency department with pneumonia or bronchiolitis were infected with the COVID-19 virus. This virus was the most frequent pathogen in all patients and in the pneumonia subgroup. However, hRSV was the leading virus in those with bronchiolitis. Twenty pneumonia cases and one bronchiolitis case had negative PCR results.

| Variables | All N = 102 (100.0%) | Pneumonia N = 97 (95.1%) | Bronchiolitis N = 5 (4.9%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hRSV | 21 (20.6) | 18 (18.6) | 3 (60.0) |

| hMPV | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| hBOV | 8 (7.8) | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| hAdV | 8 (7.8) | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| hRV | 9 (8.8) | 8 (8.2) | 1 (20.0) |

| hPIV2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| hPIV3 | 7 (6.9) | 7 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| hPIV4 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| COVID-19 (without coinfection with other viruses) | 22 (21.6) | 21 (21.6) | 1 (20.0) |

| COVID-19 + hRSV | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| COVID-19 + hRSV + hRV | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| COVID-19 + hPIV | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| NL-63 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| HKU-1 | 4 (3.9) | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Influenza virus | 9 (8.8) | 9 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| hPIV1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations: hRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; hBOV, human bocavirus; hAdV, human adenovirus; hRV, human rhinovirus; hPIV, human parainfluenza virus; NL-63, human coronavirus NL63; HKU-1, human coronavirus HKU1.

Table 3 indicates the results of laboratory tests and the clinical progress of admitted individuals. There were no significant differences regarding major blood cell counts, inflammatory markers, and conditions throughout hospitalization, except for the monocyte count, which was considerably higher in bronchiolitis cases. Three patients died of pneumonia during hospitalization.

| Variables | All N = 102 (100.0%) | Pneumonia N = 97 (95.1%) | Bronchiolitis N = 5 (4.9%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/C (+) | 3 (4.1) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CSF/C (+) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CXR involvement | 48 (66.7) | 47 (69.1) | 1 (25.0) | |

| CT-Scan/ involvement | 20 (74.1) | 20 (74.1) | ||

| Need to intubation | 4 (3.9) | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Need to CPAP | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Death | 3 (2.9) | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Length of hospitalization | 4.85 ± 4.43 | 4.95 ± 4.52 | 3.00 ± 0.71 | 0.340 b |

| PH | 7.41 ± 0.11 | 7.40 ± 0.09 | 7.49 ± 0.28 | 0.116 b |

| pCO2 | 32.59 ± 8.54 | 32.25 ± 8.31 | 38.00 ± 11.60 | 0.194 b |

| HCO3 | 20.05 ± 4.76 | 20.01 ± 4.87 | 20.65 ± 2.65 | 0.798 b |

| WBC (*1000) | 10.31 ± 5.61 | 10.31 ± 5.74 | 10.36 ± 3.12 | 0.984 b |

| Polymorphonuclear | 53.09 ± 22.41 | 54.70 ± 21.37 | 25.46 ± 24.15 | 0.052 b |

| Lymphocytes | 35.87 ± 21.04 | 34.57 ± 20.39 | 58.20 ± 21.60 | 0.069 b |

| Monocytes | 8.96 ± 3.70 | 8.70 ± 3.57 | 13.34 ± 3.39 | 0.035 b |

| Eosinophils | 1.11 ± 2.19 | 1.06 ± 2.10 | 2.00 ± 3.71 | 0.353 b |

| ESR | 31.09 ± 28.89 | 31.61 ± 29.16 | 19.75 ± 21.87 | 0.425 b |

| CRP | 26.20 ± 45.18 | 27.33 ± 46.18 | 6.98 ± 12.08 | 0.330 b |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cells; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, c-reactive protein; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CSF/C, cerebrospinal fluid culture; CXR, chest x-ray; CT-Scan, computed tomography scan.

a Values are expressed as No (%) or mean ± SD.

b Chi-square test.

5. Discussion

We found that 25.4% of cases presented to the Akbar emergency department with pneumonia or bronchiolitis were infected with the COVID-19 virus. This virus was the most frequent pathogen in all patients and in the pneumonia subgroup, while hRSV was the leading virus in those with bronchiolitis. Notably, CAP in children is the most common cause of death in children under five years old. More than 90% of severe CAP cases occur in middle and low-income countries, with higher rates of mortality and morbidity compared to high-income countries (10). Severe bronchiolitis is a leading cause of hospital admission in the first years of life and can lead to significant morbidity, including recurrent wheezing attacks or asthma, reported in 20 to 30 percent of patients (11).

The severe acute respiratory SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has altered the epidemiological distribution of other viral infections across all age groups. For example, RSV epidemics have disappeared in some countries, while in others, their seasonality has become unpredictable and unusual (7). These changes in viral circulation are evident and require more detailed epidemiological investigations in various regions, without assuming temperature as an influential factor (12). Reports of changes in the incidence of respiratory viruses during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted us to investigate the current situation in our hospitals regarding lower respiratory tract viral infections and coinfections with COVID-19 over one year.

In our study, SARS-CoV-2 and RSV were the most commonly detected viruses in the overall target population and in patients admitted with pneumonia, respectively. In children with bronchiolitis, RSV was slightly more frequent. Coinfection with COVID-19 was rare, and most SARS-CoV-2 cases had isolated infections. A systematic review pooling data from 16,643 COVID-19 patients found that viral coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is relatively low but more fatal and associated with increased dyspnea. This review also noted that coinfections are three times higher in children than in adults, with the most common coinfecting agents being influenza virus (1.54) and rhinovirus (1.32) (13). Another meta-analysis on suspected COVID-19 cases revealed that during the pandemic, influenza virus and RSV infected 4% and 2% of the population, respectively, with higher test positivity in molecular-negative COVID-19 patients compared to molecular-positive individuals (14). Pre-pandemic research indicated that RSV and human adenovirus (hAdV) were the leading causes of pneumonia in children globally, with over 20% frequency worldwide, regardless of national income or WHO region (15). Comparing pre-pandemic and pandemic data supports the hypothesis that an epidemiological change in the incidence and frequency of viral infections occurred due to the rise in pneumonia cases with SARS-CoV-2.

Indeed, common viruses such as RSV, COVID-19, and influenza are typically seasonal, with low rates of coinfections, especially in children who have less social contact and usually present with mild COVID-19 symptoms (16). A multicenter Japanese study including data from 82 hospitals reported a significant decrease (44 - 53%) in the number of patients admitted with CAP between the same six months in 2019 and 2020, particularly in those under 20 years old. Improved personal hygiene and social distancing protocols helped reduce the spread of these infections (17).

Given the small sample size of bronchiolitis cases compared to pneumonia cases in our study, our epidemiologic results regarding bronchiolitis are not robust. In contrast to our finding of a 40% frequency of COVID-19 infection in acute bronchiolitis cases, a large cross-sectional Spanish study found that only 12 out of 666 COVID-19 infected and hospitalized children met the criteria for acute bronchiolitis (18). Another study over ten months on epidemiological changes during the pandemic found only one SARS-CoV-2 case among 1116 bronchiolitis patients, confirming a decrease in the frequency of viral infections. Reoccurrence and season change of bronchiolitis and its associated agents like RSV could result from a decline in adherence to health guidelines (12).

In our study, cough was the most common clinical symptom in both pneumonia and bronchiolitis groups, with a higher prevalence of fever in children with pneumonia. Therefore, children presenting with fever and cough should be examined for pneumonia. Lung auscultation and respiratory rate measurements should be performed accurately to diagnose pneumonia. These clinical manifestations in pneumonia patients were similar to conditions before the COVID-19 pandemic (19).

Respiratory and heart rates were significantly higher in patients with bronchiolitis, likely because the average age of bronchiolitis patients was lower than that of pneumonia patients, and infants naturally have higher rates. Both groups had rates higher than the normal range for their age, consistent with the clinical manifestations of pneumonia and bronchiolitis (20). Inflammatory markers were higher in children with pneumonia, but these differences were not significant, and due to the small number of infants with bronchiolitis, these findings cannot be generalized. Larger sample sizes are needed for more accurate studies.

We suggest future researchers consider and modify the following limitations in their studies. First, bacterial pneumonia or concurrent infections caused by bacteria, fungi, or rarely parasites should be included, as about 33% of coinfections with bacteria have been reported, which might present differently compared to our findings. These coinfections were not assessed in our study due to limited financial support and research facilities. The second limitation was the lack of some data regarding laboratory and demographic measures of admitted patients.

5.1. Conclusions

The study provided valuable insights into the clinical and laboratory characteristics of pneumonia and bronchiolitis in children, including viral etiology, symptoms, clinical signs, vital signs, and laboratory findings. According to our study, cough was the most common clinical symptom in both groups of children with pneumonia and bronchiolitis, while fever was more prevalent in children with pneumonia than in those with bronchiolitis. Therefore, children presenting with fever and cough should be examined for pneumonia. Notably, both groups with pneumonia and bronchiolitis had higher rates than the normal range for their age, consistent with the clinical manifestations of these conditions.

It appears that an epidemiological shift has occurred since the pandemic started, and these trends should be carefully monitored by surveillance systems to remain aware of changes and respond appropriately. Coinfections with other viruses might be associated with a poorer prognosis for CAP patients, and screening might be beneficial in severe or critically ill patients to enable more intensive intervention. These findings can aid healthcare professionals in diagnosing and managing these common respiratory infections in hospitalized children.