1. Background

Despite a global decline in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among young individuals between 2014 and 2020 (34%), it remains a substantial public health burden in many regions worldwide (1, 2). Among children, H. pylori prevalence varies significantly across geographical areas (3). Helicobacter pylori infection is often asymptomatic during childhood, and thus routine testing is not generally recommended in young patients (4). Consequently, data on H. pylori in the young population are limited. It is important to note that findings from adult patients cannot be generalized to children due to differences in bacterial pathogenesis, host response, clinical presentation, outcomes, diagnosis, and management strategies (5).

Early diagnosis is essential for successful H. pylori eradication, which is crucial for implementing effective treatment regimens and reducing the incidence of H. pylori-associated diseases in adulthood (4). Recommendations for H. pylori testing include having a first-degree relative with gastric cancer or presenting with refractory or persistent iron deficiency and/or iron-deficiency anemia (6). While endoscopy is the recommended first-line diagnostic test for H. pylori infection, noninvasive tests with high accuracy are also available for younger patients, including the 13C urea breath test (UBT) and the stool antigen test (HpSA). However, the test specificity of UBT decreases in young children, particularly those under six years old; therefore, monoclonal HpSA testing is considered more suitable for this age group (1).

Numerous studies are currently being conducted to explore potential risk factors for the development of gastric cancer later in life, with lifestyle choices and dietary habits playing crucial roles in the emergence of H. pylori infection. Consuming pickled, fermented, smoked, or salty foods has been associated with a higher risk of H. pylori infection (7, 8); however, a study by Shinchi et al. (9) found a negative association. Additionally, diets high in carbohydrates and simple sugars have been linked to an increased risk of H. pylori infection (10).

Dietary pattern analysis has become a valuable approach in nutritional epidemiology for assessing the relationship between diet and health (11). Among the healthiest dietary patterns, the Mediterranean diet (MD) emphasizes high consumption of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fish, and poultry, while limiting red meat to less than two servings per week and allowing modest amounts of alcohol (primarily wine) (12). The MD has been linked to reduced insulin resistance and abdominal obesity, as well as to a lower risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (13, 14). Interestingly, some MD components—such as whole grains, vegetables, legumes, vegetable oils, nuts, and seeds—have shown protective effects against the pathological impacts of H. pylori infection in adults (15). Furthermore, several studies have reported that regular consumption of fruits, vegetables, and antioxidants may protect against H. pylori infection (9, 16). Eslami et al. (17) also found that reduced intake of raw vegetables was significantly associated with a higher risk of H. pylori infection.

Since 2019, Lebanon has been grappling with a severe economic crisis that has resulted in increased rates of unemployment, inflation, and poverty (18, 19). The Lebanese pound’s purchasing power has fallen by over 90%, and limited household finances have further restricted access to food and essential health services, including affordable diagnostics for infectious diseases (18). These factors underscore the gravity of the situation and the need for further evaluations and strategies to promote health and well-being.

2. Objectives

The present cross-sectional study was designed to examine the association between H. pylori infection during the economic crisis among young population in a suburban area of Northern Lebanon.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Data Collection

A cross-sectional study was conducted between June 2023 and November 2023 in the pediatric gastroenterology departments of two hospitals in a suburban area in Northern Lebanon. Participants were excluded if they had received antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and/or bismuth therapy within two weeks prior to the study. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Beirut Arab University (2023-H-0149-HS-R-0523). Written informed consent was required from parents or legal guardians before data collection. Data were gathered using a multicomponent questionnaire, which included four sections to assess sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral factors, and adherence to the MD. Anthropometric measurements were also recorded.

3.2. Anthropometric Variables and Sociodemographic Characteristics

Age, gender, income, and other sociodemographic details were collected. Behavioral risk factors included sources of drinking water, weekly consumption of poultry, raw vegetables, and meat, and hygiene practices such as washing fruits and vegetables. The KIDMED Index, consisting of 16 questions with a scoring range of -4 to 12, was used to evaluate MD adherence. Negative responses (e.g., skipping breakfast, frequent visits to fast-food restaurants, consuming pastries for breakfast, or daily sweets) were scored -1, while positive responses were scored +1. Adherence levels were categorized as poor (score ≤ 3), moderate (score 4 - 7), and high (score ≥ 8) (20). Weight (kg) and height (m²) percentiles were used to determine overweight and obesity, with a weight-for-height value at or above the 85th percentile indicating overweight, and at or above the 95th percentile indicating obesity, based on age- and sex-specific Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (21).

3.3. Helicobacter pylori Stool Antigen Test

The H. pylori CHEK™ test is a sandwich enzyme immunoassay using multiple monoclonal anti-H. pylori antibodies. All collected stool samples were stored at -20°C until testing. Tests were conducted in duplicate per the manufacturer's instructions, and results were read by spectrophotometry. Samples with absorbance values of 0.12 or above at 450 nm, or 0.08 at 450/620 nm or 450/630 nm, were considered positive for H. pylori infection. Watery stool samples were excluded from the analysis.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe the study population's behavioral, sociodemographic characteristics, and adherence to the MD. The chi-squared test identified variables linked to H. pylori infection. A binary logistic regression model—with H. pylori infection (yes/no) as the dependent variable—was executed using stepwise forward modeling. Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS/PC version 23.0), with statistical significance set at a P-value of less than 0.05.

4. Results

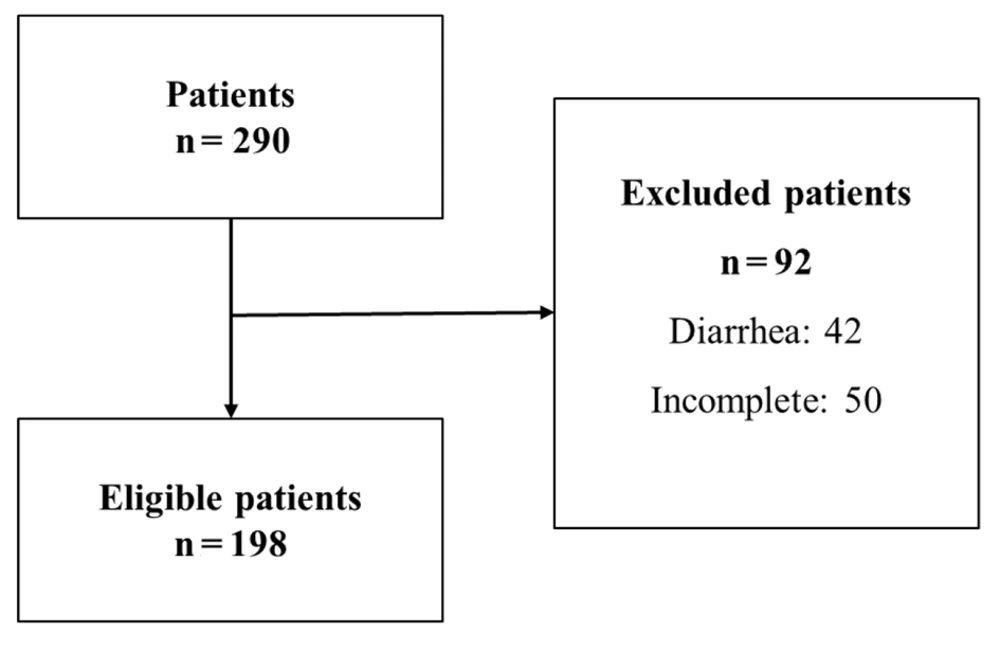

A total of 290 children and adolescents, aged between 2 and 18 years, visited the pediatric gastroenterology departments. Of these, 198 participants (51.5% male, 48.5% female) met the eligibility criteria and were included in the study (Figure 1). The average age of the participants was 4.52 ± 3.19 years. Excessive body weight was common, with 46.5% of participants classified as overweight or obese. Regarding MD adherence, only 4.1% of the children and adolescents reported high adherence. Additionally, the majority reported frequent consumption of poultry (76.8%) and raw vegetables (86.4%), with 23.2% consuming raw meat.

Fecal analysis detected H. pylori antigen in 12.1% of stool samples. Bivariate analysis showed no significant differences in H. pylori infection across age, gender, monthly income, source of drinking water, or consumption of raw animal products, fruits, and vegetables (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Anthropometric assessment revealed no association between weight-for-height percentile and H. pylori infection. However, a statistically significant difference was observed between H. pylori infection and infrequent washing of fruits and vegetables (P = 0.039).

| Variables | Total (%) | Helicobacter pylori Infection | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive; 24 (12.1) | Negative; 174 (87.9) | |||

| Age, y | 0.089 | |||

| ≤ 5 | 137 (69.19) | 13 (9.49) | 124 (90.51) | |

| > 5 | 61 (30.81) | 11 (18.03) | 50 (81.97) | |

| Gender | 0.476 | |||

| Male | 102 (51.5) | 14 (13.7) | 88 (86.3) | |

| Female | 96 (48.5) | 10 (10.4) | 86 (89.6) | |

| Monthlyincome | 0.738 | |||

| Sufficient | 38 (19.2) | 4 (10.5) | 34 (89.5) | |

| Insufficient | 160 (80.8) | 20 (12.5) | 140 (87.5) | |

| Weight-for-height | 0.692 | |||

| Underweight (< 5th percentile) | 16 (8.1) | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | |

| Normal weight (5th - 84th percentile) | 90 (45.5) | 13 (14.4) | 77 (85.6) | |

| Overweight (85th - 94th percentile) | 30 (15.2) | 4 (13.3) | 26 (86.7) | |

| Obese (≥ 95th percentile) | 62 (31.3) | 5 (8.1) | 57 (91.9) | |

| Sources of drinking water | 0.348 | |||

| Tap water | 67 (33.8) | 11 (16.4) | 56 (83.6) | |

| Mineral water | 91 (46) | 8 (8.8) | 83 (91.2) | |

| Others | 40 (20.2) | 5 (12.5) | 35 (87.5) | |

| Consumption of poultry | 0.827 | |||

| Yes | 152 (76.8) | 18 (11.8) | 134 (88.2) | |

| No | 46 (23.2) | 6 (13) | 40 (87) | |

| Consumption of raw vegetables | 0.524 | |||

| Yes | 171 (86.4) | 19 (11.2) | 150 (88.8) | |

| No | 27 (13.6) | 5 (18.5) | 22 (81.5) | |

| Consumption of raw meat | 0.802 | |||

| Yes | 46 (23.2) | 5 (11.1) | 40 (88.9) | |

| No | 152 (76.8) | 19 (12.5) | 133 (87.5) | |

| Washing fruits & vegetables before eating | 0.039 b | |||

| Yes | 181 (91.4) | 24 (13.26) | 162 (89.5) | |

| No | 17 (8.6) | 5 (29.5) | 12 (70.6) | |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

b Significant at the level of P ≤ 0.05.

Regarding the impact of the MD on H. pylori infection, two factors showed statistically significant differences: Olive oil and dairy product consumption (Table 2). Specifically, H. pylori infection was less frequent among patients who consumed olive oil (8.5%) compared to those who did not include olive oil in their diet (19.1%) (P = 0.029). Likewise, more positively diagnosed cases (20.4%) were noted among participants who reported daily consumption of dairy products for breakfast, compared to those who did not consume dairy products regularly (9.4%) (P = 0.040).

| Variables | Total | Helicobacter pylori Infection | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive; 24 (12.1) | Negative; 174 (87.9) | |||

| One fruit daily | 0.730 | |||

| No | 52 (26.3) | 7 (13.5) | 45 (86.5) | |

| Yes | 146 (73.7) | 17 (11.6) | 129 (88.4) | |

| Two fruits daily | 0.783 | |||

| No | 127 (64.1) | 16 (12.6) | 111 (87.4) | |

| Yes | 71 (35.9) | 8 (11.3) | 63 (88.7) | |

| One vegetable daily | 0.600 | |||

| No | 57 (28.8) | 8 (14) | 49 (86) | |

| Yes | 141 (71.2) | 16 (11.3) | 125 (88.7) | |

| > 1 vegetable daily | 0.988 | |||

| No | 140 (70.7) | 17 (12.1) | 123 (87.9) | |

| Yes | 58 (29.3) | 7 (12.1) | 51 (87.9) | |

| Fish (2 - 3 times/week) | 0.598 | |||

| No | 196 (99) | 24 (12.2) | 172 (87.8) | |

| Yes | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |

| > 1 fast food meal/week | 0.813 | |||

| No | 153 (77.3) | 19 (12.4) | 134 (87.6) | |

| Yes | 45 (22.7) | 5 (11.1) | 40 (88.9) | |

| Pulses > once/week | 0.511 | |||

| No | 61 (30.8) | 6 (9.8) | 55 (90.2) | |

| Yes | 137 (69.2) | 18 (13.1) | 119 (86.9) | |

| Cereals for breakfast | 0.205 | |||

| No | 53 (26.8) | 9 (17) | 44 (83) | |

| Yes | 145 (73.2) | 15 (10.3) | 130 (89.7) | |

| Pasta/rice daily | 0.624 | |||

| No | 75 (37.9) | 8 (10.7) | 67 (89.3) | |

| Yes | 123 (62.1) | 16 (13) | 107 (87) | |

| Nuts daily | 0.699 | |||

| No | 168 (84.8) | 21 (12.5) | 147 (87.5) | |

| Yes | 30 (15.2) | 3 (10) | 27 (90) | |

| Frequent consumption of olive oil | 0.029 b | |||

| No | 68 (34.3) | 13 (19.1) | 55 (80.9) | |

| Yes | 130 (65.7) | 11 (8.5) | 119 (91.5) | |

| Skipping breakfast | 0.955 | |||

| No | 133 (67.2) | 16 (12) | 117 (88) | |

| Yes | 65 (32.8) | 8 (12.3) | 57 (87.7) | |

| Dairy for breakfast | 0.040 b | |||

| No | 49 (24.7) | 10 (20.4) | 39 (79.6) | |

| Yes | 149 (75.3) | 14 (9.4) | 135 (90.6) | |

| Pastries for breakfast | 0.672 | |||

| No | 107 (54) | 12 (11.2) | 95 (88.8) | |

| Yes | 91 (46) | 12 (13.2) | 79 (86.8) | |

| > 2 yogurts or cheese daily | 0.089 | |||

| No | 135 (68.2) | 20 (14.8) | 115 (85.2) | |

| Yes | 63 (31.8) | 4 (6.3) | 59 (93.7) | |

| Sweets daily | 0.771 | |||

| No | 69 (34.8) | 9 (13) | 60 (87) | |

| Yes | 129 (65.2) | 15 (11.6) | 114 (88.4) | |

| Adherence to the MD | 0.161 | |||

| Poor adherence | 68 (34.3) | 12 (17.6) | 56 (82.4) | |

| Moderate adherence | 122 (61.6) | 12 (9.8) | 110 (90.2) | |

| High adherence | 8 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Significant at the level of P ≤ 0.05.

A multiple binary logistic regression analysis was performed on the factors that showed significant association with H. pylori infection in the bivariate analysis: Washing fruits and vegetables before eating, and consumption of olive oil and dairy products. The results are summarized in Table 3. Children and adolescents who consumed olive oil (OR = 2.508; 95% CI = 1.005 - 6.257; P = 0.045) and dairy products (OR = 2.692; 95% CI= , 1.057 - 6.852; P = 0.038) were less likely to be infected with H. pylori compared to those who did not include these food items in their diet. The remaining variables did not show any significant association with H. pylori.

a Significant at the level of P ≤ 0.05.

5. Discussion

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess adherence to the MD in the young Lebanese population during the economic crisis and its association with H. pylori infection. Our results indicate that more than one-third of the participants had low adherence to the MD. This could be explained by limited financial means to procure food, as approximately 80% of the sample was classified as having low socioeconomic status based on monthly income. Another possible reason could be a lack of awareness regarding the health benefits of adhering to this dietary pattern.

Helicobacter pylori was detected in 12.1% of children and adolescents. A lower prevalence has been documented in Japan (3.7%) (22), whereas higher prevalence rates have been reported in Iran (64.2%) and African countries, including Uganda (24.3%), Cameroon (52.27%), and Egypt (64.6%) (23-26). These disparities may be attributed to factors like poor sanitation and untreated water supplies (27). Furthermore, we examined the association between H. pylori infection and various patient characteristics, including anthropometric, sociodemographic, and behavioral factors. Bivariate analysis revealed a statistical association between H. pylori infection and infrequent washing of fruits and vegetables before eating, supporting the hypothesis by some authors that H. pylori may be transmitted as a foodborne pathogen (28, 29). However, this factor did not remain statistically significant in the multiple binary logistic regression analysis.

Recently, several studies have explored the potential relationship between dietary patterns and the risk of gastric cancer. Higher adherence to the MD has been linked to a reduced risk of gastric cancer and its subtypes (30, 31). In Lebanon, the MD is widely followed as a primary dietary pattern, prompting us to investigate its association with H. pylori infection. Our findings showed that the overall MD score was not associated with H. pylori infection. However, when analyzing specific components of the MD, the consumption of olive oil and dairy products were found to be associated with H. pylori infection.

Previous studies have demonstrated a strong antibacterial effect of olive oil phenolics against H. pylori in vitro (32). Additionally, two olive-leaf extracts were shown to reduce IL-8 secretion and suppress reactive oxygen species production in human gastric cells infected with H. pylori, highlighting olive oil's potential in mitigating the pathogenic effects of H. pylori infection (33). These beneficial properties may be due to olive oil’s and olive leaf extract’s capacity to bind metal ions, which slow free radical production (34), as well as their ability to inhibit various inflammatory enzymes, including lipoxygenases (35).

Milk and dairy products are important sources of essential micronutrients such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, zinc, and phosphorus (36). The relationship between dairy products and H. pylori is controversial. Some cohort studies have shown an association between increased dairy consumption and a reduced risk of gastric cancer in H. pylori–positive patients (37), while other case-control studies found no association (38). Focusing on probiotic dairy products, a randomized control trial revealed that the average clearance rates of H. pylori were higher in the probiotic group than in the conventional therapy (control) group. The beneficial effect of probiotics in eradicating H. pylori includes promoting anti-inflammatory and antioxidative mechanisms and modulating the intestinal microbiota (39). Additionally, vitamin D3 in dairy products has been shown to stimulate the synthesis of antibacterial components, enhancing antimicrobial activity across various cell types (40). Furthermore, vitamin D3 supplementation in healthy human stomach epithelial cells has demonstrated anti-H. pylori activity. H. pylori infection can alter the release of Ca2+ from lysosomes in gastric epithelial cells, allowing its survival in the gastric epithelium (41).

This is the first study to assess the association between the MD and H. pylori infection in Lebanon. However, some limitations should be noted. The sample consisted of hospitalized patients who may have been previously diagnosed with gastrointestinal disorders, potentially leading them to modify their eating habits. Additionally, as a cross-sectional study, this research cannot establish causality. Future large-scale, multicenter epidemiological studies with comprehensive dietary assessments, such as food frequency questionnaires or 24-hour recalls, could provide a more detailed understanding of daily macronutrient and micronutrient intake.

5.1. Conclusions

This study found a significant correlation between H. pylori infection and the consumption of olive oil and dairy products. Thus, longitudinal studies on nutritional knowledge and food security are essential to further investigate dietary factors associated with poor adherence to the MD and H. pylori infection. Additionally, studies on the antimicrobial properties of natural products against H. pylori may lead to new approaches in clinical practice, especially for antibiotic-resistant strains.