1. Introduction

Group A streptococcus (GAS) typically causes tonsillitis and pharyngitis. In developed countries, immune-mediated complications of streptococcus remain a complex issue, both during acute infection (e.g., scarlet fever) and following the infection, such as rheumatic heart disease (RHD) and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN). Group A streptococcus complications are prevalent worldwide, with RHD affecting fewer than 5 million cases in 2013, while PSGN affects approximately 9.5 cases per 100,000 population annually in developing countries. This does not account for several recent scarlet fever outbreaks, which are concerning (1, 2). Very few cases show concurrent PSGN and RHD due to differences between nephrogenic and rheumatogenic strains, making cardiac complications in PSGN uncommon. Unfortunately, the inflammatory response caused by group A streptococcus, including PSGN, can progress to dilated cardiomyopathy and fulminant myocarditis with high mortality (3). Although echocardiograms have become more accessible and show benefits for diagnosing RHD, they are rarely used for PSGN (4). We describe three cases of Indonesian children with cardiac-related post-streptococcal complications, compare the results, and review them based on echocardiogram findings.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case 1

An 8-year-old female presented with recurring palpitations and exhaustion for two weeks. She had a history of polyarthralgia one week prior and recurring flu-like symptoms. Other than this, her medical history was unremarkable. Her vital signs showed normotension and a normal respiration rate, but she had tachycardia. Physical examination revealed mild underweight, a pansystolic murmur graded IV/VI at the mitral valve, and a murmur graded III/VI at the tricuspid valve, with S3 gallops but no rhonchi.

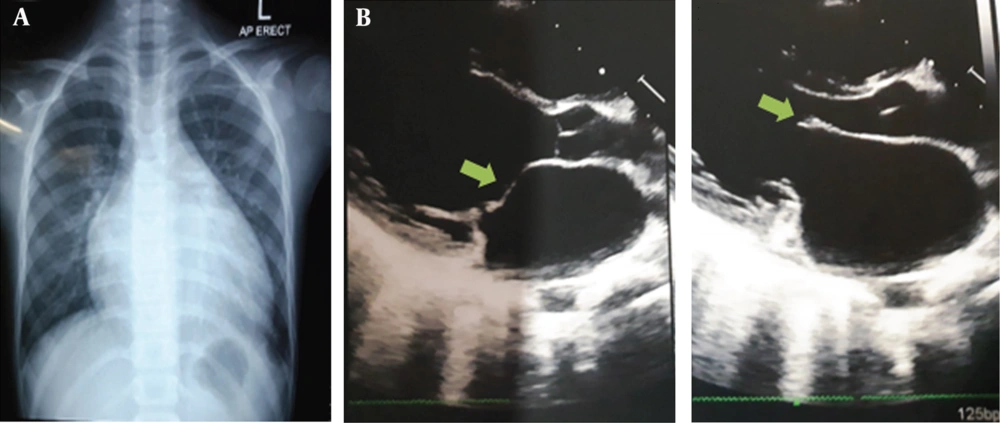

Further examination revealed increased anti-streptolysin O (ASO) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, along with thrombocytosis and 10% monocytes (Table 1). A chest X-ray (Figure 1A) showed cardiomegaly with left atrial (LA) enlargement, consistent with her ECG findings. Transthoracic echocardiography (Figure 1B) revealed LA and left ventricular (LV) dilatation with normal systolic function, global normokinesis, and an ejection fraction (EF) of 63.5%. Severe mitral regurgitation (MR) with a flail anterior mitral leaflet (AML) was noted, along with moderate tricuspid regurgitation (TR), mild aortic and pulmonary regurgitation, and mild pulmonary hypertension. She was diagnosed with acute rheumatic fever carditis and treated with erythromycin 200 mg qid, furosemide 20 mg, captopril 6.25 mg bid, spironolactone 6.25 mg, high-dose aspirin, and prednisone. She was managed effectively, and her antibiotic regimen was adjusted to a prophylactic dose. Due to limited facilities, she was referred for long-term prophylaxis.

| Parameters | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.7 | 11.9 | 11.7 |

| WBC (/µL) | 13,000 | 9,500 | 11,400 |

| WBC diff count | Monocyte 10% | Lymphocyte 47% | Within normal range |

| Platelets (/µL) | 591,000 | 673,000 | 389,000 |

| ASTO (IU/mL) | 800 | 800 | 400 |

| Electrolyte: K, Na, Cl, Ca (mmol/L) | Normal | Normal | K 5.8 |

| Blood urea (mg/dL) | Normal | Normal | 82 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | Normal | Normal | 1.5 |

| C-reactive protein | (+) | (+) | -- |

| Others | -- | -- | Albumin: 2.7 g/dL; urinalysis; haematuria 3+, proteinuria 1+ |

Abbreviation: WBC, white blood cells.

a Normal value: Hemoglobin = 12.0 - 15.0; WBC = 4,500 - 13,400; platelets = 150,000 - 450,000; monocyte = 2 - 8%; lymphocyte = 20 - 40%; ASTO ≤ 200; blood urea = 14.9 - 35.9; creatinine = 0.73 - 1.18; albumin = 3.5 - 5.2.

A, case 1 chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly and pulmonary congestion; B, echocardiography PLAX showed left atrial (LA) and left ventricular (LV) dilatation, global normokinetic, and severe mitral regurgitation (MR). Excessive motion in flail anterior mitral leaflet (AML) with suspicion of distal tip restriction or thickening and impinged towards LV outflow tract during diastole (green arrow).

2.2. Case 2

A 10-year-old female was admitted to the emergency department with hemoptysis, worsening dyspnea, and ankle swelling for three days, along with a history of polyarthralgia. She had been evaluated by a pediatrician and cardiologist a month earlier, but admission for acute rheumatic fever (ARF) with suspected vegetation was refused. Her medications included aspirin, furosemide, ramipril, erythromycin prophylaxis, spironolactone, and prednisone, which had run out about a week ago. Vital signs were normotensive, with mild tachypnea, tachycardia, and normal oxygen saturation. Physical examination revealed increased jugular venous pressure, bibasilar rales, bilateral ankle swelling, and pansystolic murmurs at the mitral and tricuspid valves graded V/VI, but no additional signs of infective endocarditis. Her weight at admission was 27 kg.

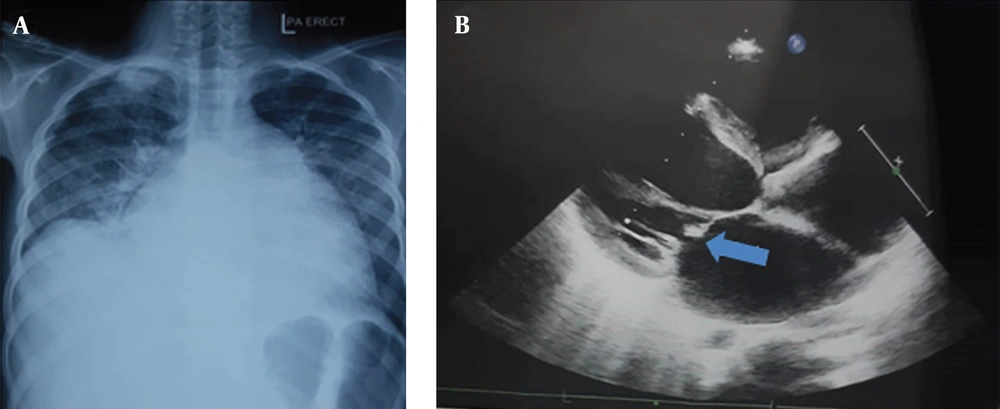

Her laboratory results are shown in Table 1. The ECG showed LA enlargement, and the chest X-ray (Figure 2A) indicated cardiomegaly. An echocardiogram performed last month (Figure 2B) revealed four-chamber dilatation with normal systolic function, global normokinesis (EF 69%), severe MR with suspected vegetation on a flail AML, severe TR, and mild pulmonary regurgitation (PR). A follow-up echocardiogram during admission showed no vegetation, but the flail AML and posterior mitral leaflet (PML) abnormalities persisted. She was diagnosed with suspected reactivation of rheumatic heart disease. We increased the erythromycin dose and added sildenafil 6.25 mg bid. After discharge, she remained well and was referred to a tertiary center for long-term prophylaxis and treatment consideration.

A, case 2 chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly and pulmonary congestion; B, echocardiography PLAX one month ago showed RA, left atrial (LA), and left ventricular (LV) dilatation, global normokinetic, and mitral regurgitation (MR) severe with suspected vegetation on the anterior mitral leaflet (AML) (blue arrow).

2.3. Case 3

A 9-year-old male presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, vomiting for three days, and newly recognized swollen eyes. He had experienced a sore throat a week ago and had been treated with over-the-counter medication. His family reported no new medications or history of allergies. Vital signs revealed diastolic hypertension with tachycardia, mild tachypnea, and normal oxygen saturation. Physical examination showed right-side rales, bilateral palpebral edema, and an S3 gallop, but no ankle swelling or increased jugular venous pressure. His BMI was normal, and he weighed 25 kg at admission.

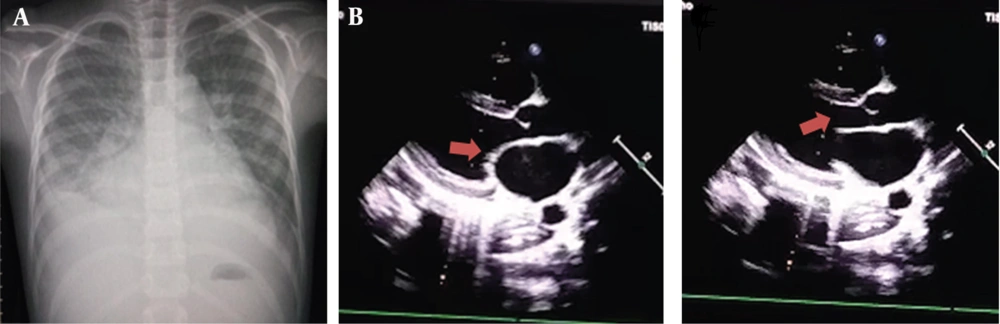

The chest X-ray (Figure 3A) revealed pleural effusion and cardiomegaly. Laboratory results are shown in Table 1, and the patient was diagnosed with acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis. Treatment with fluid restriction, antibiotics, captopril, and furosemide was initiated. On day 3, his condition and edema worsened, with leukocytosis (30,100), metabolic acidosis, and elevated CRP, ALT, AST, and blood urea. He was evaluated by a cardiologist, and an echocardiogram (Figure 3B) revealed four-chamber dilatation, global hypokinesis (EF 32%), severe MR and TR, mild PR, and slight pericardial effusion. We increased the furosemide dose, corrected hypoalbuminemia, and added digoxin, ivabradine, and low-dose aspirin. The antibiotic was changed from cefotaxime to meropenem. By day 9, the patient was discharged, with improvements noted on follow-up chest X-rays. He was referred for long-term prophylaxis.

A, case 3 chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and pleural effusion; B, echocardiography PLAX showed four chamber dilatation and global hypokinetic, slight pericardial effusion, severe mitral regurgitation (MR) and severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR), without any excessive motion and no thickening or impingement (red arrow).

3. Discussion

The mitral leaflet motion and morphology, particularly the presence of excessive leaflet motion and distal tip morphology, are beneficial as indicators of acute mitral changes and are pathognomonic for RHD in the pediatric setting. These findings help differentiate between RHD and PSGN. Whether the vegetation is part of ARF or not, further investigation is still warranted. Additionally, an echocardiogram should be considered in PSGN with deteriorating or heart failure symptoms so that it can be managed early before progressing into dilated cardiomyopathy.

Rheumatic heart disease is recognized as a global burden with long-term morbidity and 275,000 deaths yearly, with a high prevalence in Australia and Asia, compared to acute PSGN, which has declined worldwide except in low-to-middle-income countries where the risk of nephritis from throat infection is around 5%. Transmission through the respiratory tract and skin infection may increase the odds in a high-density population with poor living conditions. Furthermore, genetics may play a role in the RHD immunopathologic response, as Australian Indigenous and Indonesian people are part of the Asia-Pacific origin (1, 2).

Prevalence studies of subclinical RHD in Indonesia, Tanzania, and Bharat revealed 20 cases per 250, 34 per 1,000, and 20 per 1,000 children, respectively. Additionally, the prevalence of clinical RHD is around 1 per 1,000 children in both Tanzania and Bharat, contrasting with ARF incidence, which is only 30 per 100,000. The difference in numbers is concerning since subclinical cases rarely show symptoms and may be detected years afterward, which warrants prevention by early screening for subclinical RHD in endemic countries, especially in schools (4-6).

Echocardiography remains a highly specific and sensitive tool for diagnosing RHD. All patients exhibited severe mitral regurgitation (excluding other causes), which is pathognomonic for RHD based on the World Heart Federation’s criteria. Flail leaflet motion is defined as excessive leaflet tip motion due to elongation of the primary chordae, resulting in displacement of the tip, particularly the AML. This condition leads to severe regurgitation and normalized ejection fraction when compared to case 3, which showed normal leaflet motion and reduced ejection fraction due to eccentric myocardial remodeling with annular dilatation. Additionally, the impingement of AML might be part of the “flail” due to chordae elongation (unrestricted motion) and valvular inflammation. These findings help differentiate between carditis in PSGN and ARF (i.e., rheumatic valvulitis). The study by Hunter et al. (7) also supported the anterior ‘distal tip’ configuration in the PLAX view as a definitive RHD criterion in all 43 school children. These findings are considered useful for diagnosis and predicting progression in individuals aged ≤ 20 years due to fewer differential etiologies (4, 7, 8). Meanwhile, PSGN is rarely associated with severe carditis, as seen in the research by Idhate et al., and the absence of specific morphology/valvulitis findings in the paper adds to the benefit of echocardiographic assessment (8).

Valvulitis is caused by antibody deposition, molecular mimicry, and reactivity from T cells, while cardiac involvement in PSGN remains enigmatic due to different strains. The SpeB proteinase, a pathogenic antigen in PSGN, suspiciously induces cross-reactive antibodies between endothelial cells, cardiac myosin, and valvular tissue. Additionally, angiotensin, cardiorenal responses, and overvolume exacerbate the damaged structure and promote eccentric remodeling (2, 9). Vegetation-like thrombosis (observed in case 2) has been noted in some autopsies during ARF. These thrombi contain macrophages, platelets, and reticular fibers during acute valvulitis, which may explain their disappearance during the second echocardiography after early treatment. Regardless, transesophageal echocardiography is still recommended to rule out potential endocarditis foci. With signs of stage C and D in cases 1 and 2, respectively, referral is essential to evaluate the need for surgery and long-term prophylaxis (4, 7, 10).

All patients were managed according to their diagnosis and referred for long-term observation. We did not administer steroids to case 3 due to a lack of evidence. In case 2, sildenafil was used in response to the history of hemoptysis with pulmonary hypertension. Meanwhile, ivabradine in case 3 was well-tolerated even in a pediatric patient with progressing myocarditis and improved LV ejection fraction, in addition to digoxin. Both require consideration and further trials, as there may be benefits from adult cardiovascular treatments. Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered for all patients, including case 3, due to cardiac involvement until no valvular sequelae are proven during follow-up echocardiography (1, 2, 11).

5.1. Conclusions

Given the long-term effects of post-streptococcal cardiac complications, we emphasize echocardiograms as a more readily available and affordable screening and assessment method, especially in endemic populations. To achieve prevention, advocacy in health systems and further research are needed to limit risk factors and control the spread of GAS and other infectious diseases, which continue to challenge cardiovascular management.