1. Background

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common infections and urinary diseases in children. If not diagnosed early and left untreated timely, UTIs can lead to scar formation, hypertension and end stage renal disease (ESRD) (1-7). There have been many efforts to study mediators of inflammation trying to halt deleterious effects of UTI such as scar formation (8-11).

Ghrelin is a regulatory hormone that increases fat tissues and body composition. Ghrelin is a 28 amino acid peptide, which is mainly produced in stomach fundus cells but is also produced in smaller amounts in other organs such as kidneys, lung, adrenals, placenta and brain (12, 13).

Ghrelin stimulates release of Growth Hormone (GH), increases food intake, and causes weight gain, mainly in fat tissue. Ghrelin increases body fat without extra calorie intake. It has been postulated that Ghrelin may make metabolism more efficient (14, 15).

Ghrelin inhibits Leptin receptor, an internal ligand for growth hormone secretion (GHS-R) (16), so it is likely that there is an association between infection and Ghrelin. In the present study, we aimed to compare Ghrelin levels in children with urinary tract infection before and after treatment.

With deterioration of renal function, Ghrelin levels increase in the body. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience muscle wasting and high fat tissue (17, 18).

However, despite elevated Ghrelin levels seen in patients with CKD, recent investigations have found that treatment with exogenous Ghrelin or Ghrelin receptor antagonists improve body composition. A study in uremic rats found that treatment with Ghrelin receptor antagonists and exogenous Ghrelin increases lean body mass and growth hormone (GH) levels and decreases inflammation (19).

2. Objectives

In the present study, we aimed to examine weather urinary Ghrelin concentration is involved in anorexia in patients with UTI and weather its urinary concentration changes with treatment; we investigated urine Ghrelin concentration before and after treatment.

3. Patients and Methods

A total of 40 patients admitted with UTI at the pediatric nephrology ward were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were: negative urine culture, no evidence of pyelonephritis on Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scan, systemic diseases and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Before treatment, urine and blood samples for Ghrelin were collected and stored at -20°C. In addition, U/A, U/C, urine Creatinine (Cr), CBC, ESR, CRP, BUN , Cr, BS, TG and cholesterol were measured. On the fifth day of admission, samplings for the above-mentioned tests were repeated. Other investigations were ultrasonography (US), Voiding Cystourethrography (VCUG) and DMSA scan (4, 5). On the last day of study, urine samples were melted and Ghrelin concentration measured with human Acylated Ghrelin Elisa kit, Eurommun company China.

Ethical issues.

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. A written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all the study participants.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using paired T test for quantitative data and Wilcoxon test for qualitative data and correlations by spearman coefficient and differences considered significant if P < 0.05.

4. Results

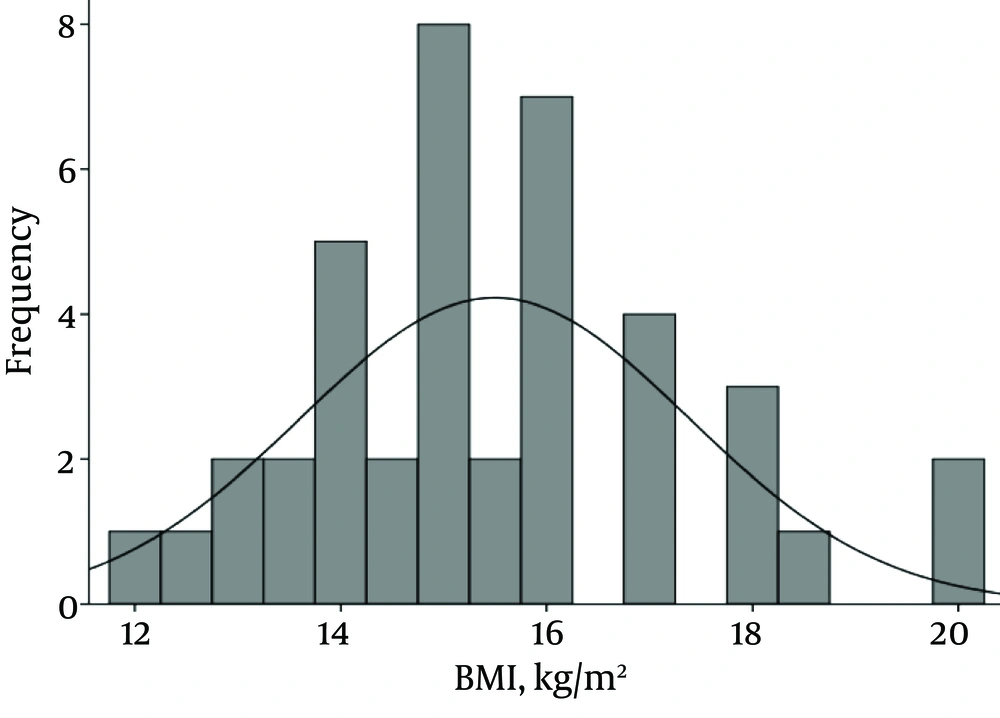

Forty patients including 34 girls (85%) and six boys (15%) were studied. Mean and standard deviation (M ± SD) for age, weight and body mass index (BMI) were 48.3 ± 46.1 (2 - 162 months), 17 ± 10.7 (4.5 - 51 kg) and 15.5 ± 1.9 (12-20), respectively. Pattern of BMI of patients is shown in Figure 1.

Based on Ultrasonographic (US) studies; hydronephrosis was detected in eight (20.5%) patients. In 29 patients, VCUG was performed, which showed Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR) in nine cases including four bilateral and five unilateral refluxes. The DMSA scan revealed reduced uptake in 22 patients (66.7%) and scar in nine cases (27.3%).

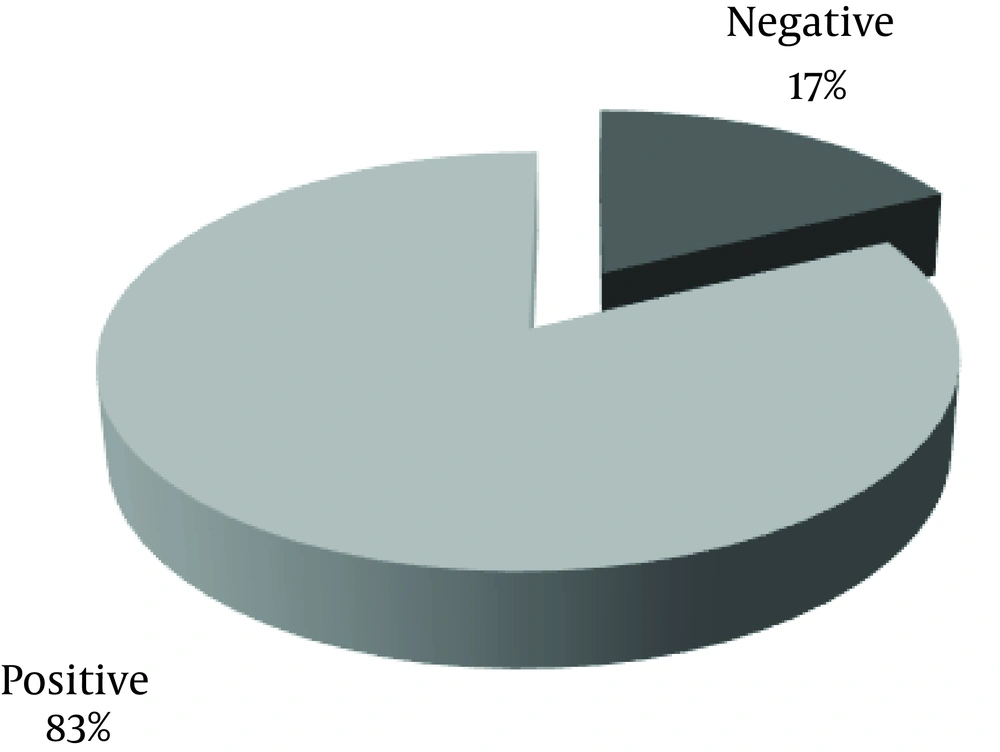

Frequency of anorexia in patients is shown in Figure 2.

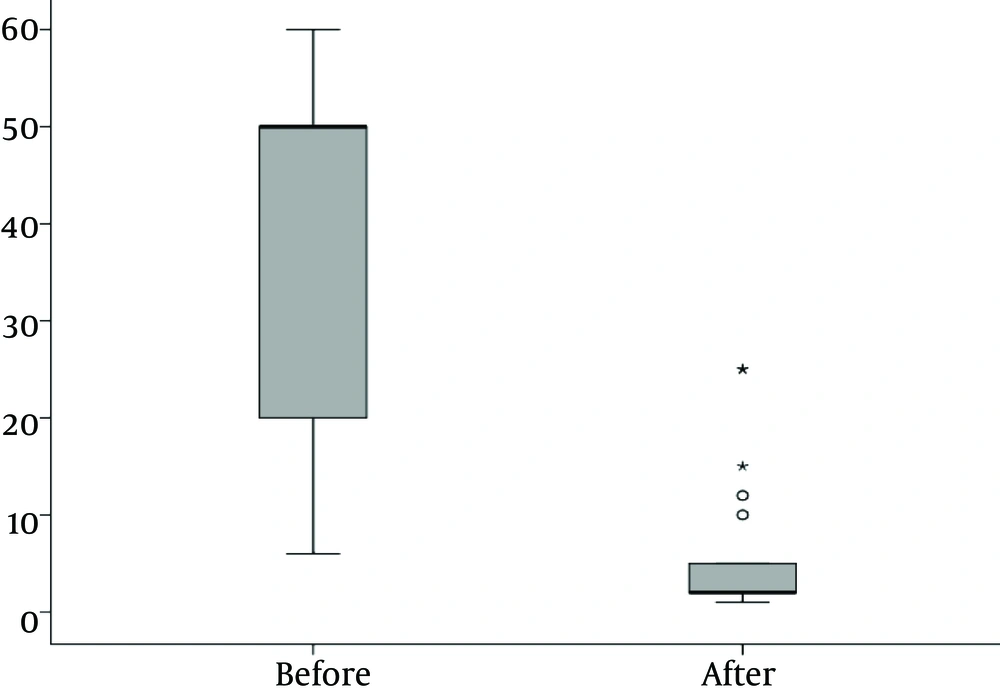

There was a significantly lower WBC and CRP after treatment than before treatment (P < 0.001).

Figure 3 depicts the number of Leukocytes in blood of patients before and after treatment.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) before treatment was 40.3 ± 26.7 (highest: 108) and after treatment 35.2 ± 20.5.

Thus reduction of ESR after treatment was not significant compared to before treatment (P < 0.282).

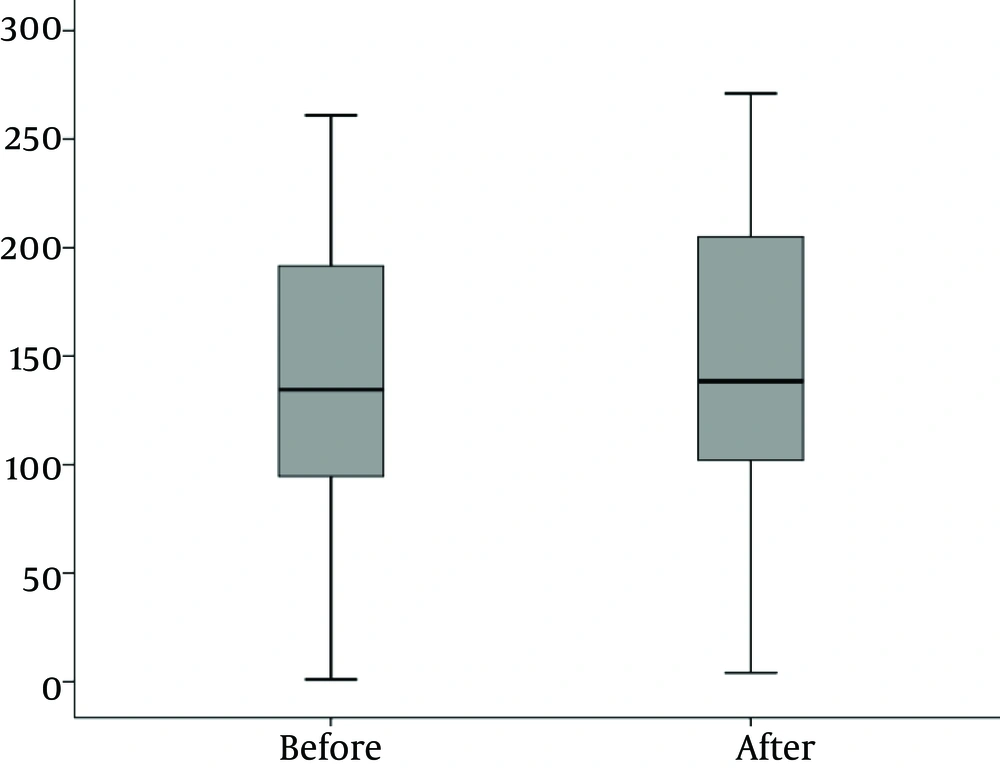

Mean urinary Ghrelin concentration before and after treatment was 138.4 ± 70.9 and147.2 ± 72.6, respectively (P < 0.001).

Mean urinary Ghrelin concentration before and after treatment is shown in Figure 4.

Mean urinary Ghrelin concentration before treatment in patients with anorexia and without anorexia was 135.0 ± 73.6 and 154.6 ± 58.4 respectively (P = 0.51).

Mean urinary Ghrelin concentration after treatment in patients with anorexia and without anorexia was 161.4 ± 59.8 and 144.2 ± 75.5respectively (P = 0.57).

So there was no significant difference in mean urinary Ghrelin concentration before and after treatment in patients with or without anorexia.

5. Discussion

In this study, we investigated urinary Ghrelin before and after treatment of UTI in 40 pediatric patients and its association with renal scar and inflammatory markers.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates urine Ghrelin concentration in pediatric UTIs.

Gunta et al. and Mak et al. studied the pathophysiology of Ghrelin and Leptin in chronic kidney disease and concluded that Ghrelin may have a role in protein energy wasting, cachexia, inflammation and cardiovascular complications in CKD patients (12, 14).

Carrero et al. in their study found that protein-energy wasting modifies the association of Ghrelin with inflammation, Leptin and mortality in hemodialysis patients (13).

In the study of Piatek et al. on urinary tract infection during pregnancy, they found that the level of Leptin, Ghrelin and insulin in maternal and placental blood was lower in pregnant women with UTI than controls (20).

Suzuki et al. in a study entitled, Ghrelin and cachexia in chronic kidney disease, treatment with Ghrelin suggested further investigations (21).

Madison et al. in their study entitled Prostacyclin signaling regulates circulating Ghrelin during acute inflammation suggested that inflammation reduces Ghrelin concentration and supported treatment with Ghrelin in acute and chronic inflammatory diseases (22).

In our study mean urinary Ghrelin concentration after treatment was significantly higher than before treatment. This supports the findings of Carrero et al. (13), Madison et al. (22), Piatek et al. (20) and some other investigators (23-25).

Although in the present study there was no significant difference in mean urinary Ghrelin concentration before and after treatment in patients with or without anorexia, we still think at least it can indirectly have a role through its effects on inflammation.

5.1. Conclusions

In this study we found that urinary Ghrelin concentration is significantly lower before treatment of UTI and significantly increases after cessation of inflammation. Further investigations are needed before suggestion of treatment with Ghrelin in patients with UTI.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

Due to some considerations regarding ethical issues for taking blood from infants and children, we were not able to obtain serum Ghrelin concentrations at the same time as urine tests. Although we had excellent contribution of most of the parents in preparing suitable urine samples, a few cases had limited cooperation.