1. Background

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common causes of human nosocomial and community-acquired infections (1, 2). The emergence of antibiotic-resistant isolates, especially methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), poses a major problem for public health (3, 4). In the past few decades, the number of macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin (MLS)-resistant isolates associated with MRSA has increased in Iran and worldwide (2, 3). Several genes, including erm(A,B,C) and msr(A/B) are involved in the resistance to macrolides and lincosamides in S. aureus strains (1, 5, 6). erm gene production of methyltransferase enzymes and methylation of the ribosomal target site by methyltransferases causes inhibition of the binding of macrolides to the target site (1, 5). Active efflux by mrs(A/B) is the other mechanism of resistance to macrolides (1, 5).

2. Objectives

Erythromycin and clindamycin are used for the treatment of staphylococcal infections, such as skin and soft-tissue infections, and as alternatives in penicillin-allergic patients (3). Therefore, the aim of this study was the molecular detection of macrolide and lincosamide-resistance genes, including erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), and mrs(A/B), in clinical MRSA isolates from Kerman, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 170 clinical isolates of S. aureus were collected from 145 inpatients and 25 outpatients at Kerman university-affiliated hospitals from February 2014 to December 2015. Bacterial isolates were identified by standard and biochemical methods, such as gram staining, catalase production, coagulase, DNase reaction, and mannitol fermentation. All of the applied culture media were purchased from Merck Co., Germany. Isolates were confirmed by detection of the nuc gene (4).

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

The antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates to gentamicin (10 µg), amikacin (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg), linezolid (30 µg), and vancomycin (vancomycin-resistance screening was done with dilution methods) was determined according to the clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) guidelines (7). S. aureus ATCC 25923 was used as the standard for antibiograms. Isolates resistant to at least three antibiotics from different classes were considered multidrug-resistant (MDR) according to the recommendations of Magiorakos et al. (8). All of the applied antibiotic disks were purchased from Mast, Inc.

3.3. Detection of MRSA

Susceptibility to cefoxitin (30 µg) (Mast Co.) was used for determination of MRSA isolates; they were then examined for the mec(A) gene (9).

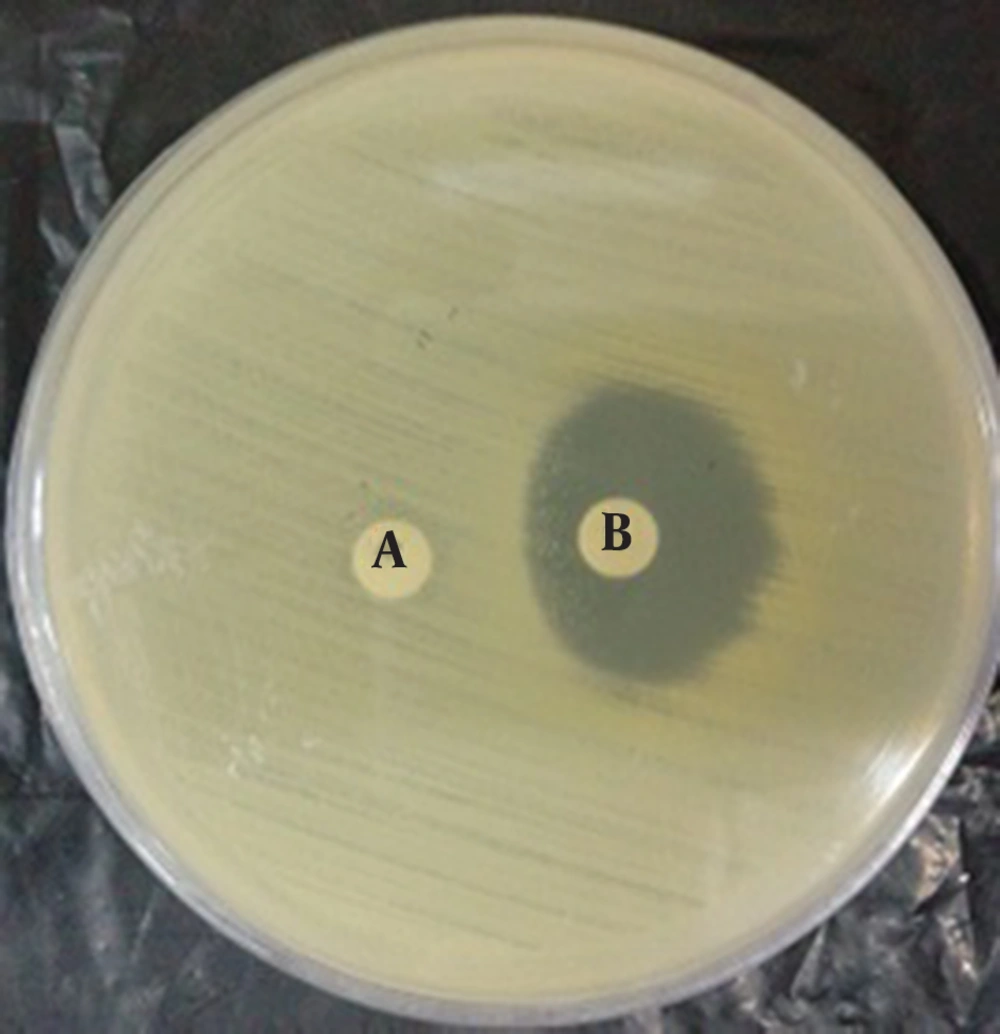

3.4. Detection of Inducible Clindamycin Resistance

Inducible clindamycin resistance was determined with the D-zone test according to the CLSI guidelines (9).

3.5. Detection of Macrolide Resistance Genes by PCR

Total DNA was extracted by the boiling method (10). For erythromycin and clindamycin-resistant isolates, the resistance genes, including erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), and mrs(A/B) were detected by the PCR method using specific oligonucleotide primers (Table 1). PCR reactions were performed in the FlexCycler2 PCR thermal cycler (Analytik Jena) using PCR master mix (Ampliqon Inc., Denmark). S. aureus strains harboring mecA, erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), and mrs(A/B) were used as positive controls for PCR. These strains were received from Dr. Mohammad Emaneini (department of microbiology, school of medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran) (11). PCR reactions were performed in total volumes of 25 μl. The master mix contained 12.5 µL of reaction mixture with Taq DNA polymerase master mix red (Ampliqon), 0.5 µL of each of the forward and reverse primers in 10 Pmol concentrations, 2 µL of target DNA, and 9.5 μl of distilled water. The PCR mixtures were subjected to 5 minutes at 96°C, followed by 30 cycles of 45 seconds at 95°C for denaturation, 45 seconds for annealing extension (Table 1), extension at 72°C for 2 minutes, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. The PCR products were revealed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and subsequent exposure to UV light in the presence of DNA Green Viewer (Pars Tous Biotechnology, Iran) load dye.

| Gene Target | Primer Sequence, 5’ - 3’ | Annealing Temperature, °C | Product Size, bp | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nuc | 60 | 279 | (4) | |

| F | GCG ATT GAT GGT GAT ACG GTT | |||

| R | AGC CAA GCC TTG ACG AAC TAA AGC | |||

| mec(A) | 56 | 162 | (10) | |

| F | TCC AGA TTA CAA CTT CAC CAG G | |||

| R | CCA CTT CAT ATC TTG TAA CG | |||

| erm(A) | 56.5 | 139 | (12) | |

| F | TAT CTT ATC GTT GAG AAG GGA TT | |||

| R | CTA CAC TTG GCT TAG GAT GAA A | |||

| erm(B) | 56.5 | 142 | (1) | |

| F | CTA TCT GAT TGT TGA AGA AGG ATT | |||

| R | GTT TAC TCT TGG TTT AGG ATG AAA | |||

| erm(C) | 55.5 | 297 | (13) | |

| F | AAT CGT CAA TTC CTG CAT GT | |||

| R | TAA TCG TGG AAT ACG GGT TTG | |||

| mrs(A/B) | 56.5 | 402 | (14) | |

| F | GCA AAT GGT GTA GGT AAG ACA ACT | |||

| R | ATC ATG TGA TGT AAA CAA AAT |

Primers Used in This Study

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (v.22.0) statistical software. We used the χ2 test for comparisons between the presence of mec(A) (MRSA isolates) and the macrolide and lincosamide-resistance genes. Differences were considered statistically significant at P-values of < 0.05.

4. Results

Out of a total of 170 S. aureus isolates, 85% (n = 145) were recovered from inpatients and 15% (n = 25) were recovered from outpatients. All of the isolates were sensitive to linezolid and vancomycin. The susceptibility test results for the other antibiotics are presented in Table 2. More than 50% of the isolates were MDR, of which 52.5% (89/170) were MRSA. Inducible clindamycin resistance was observed in 12.5% (21/170) of the isolates. The mecA, ermA, ermB, ermC, and mrsA/B genes were detected in 39.5% (69/170), 11% (19/170), 3.5% (6/170), 20.5% (35/170), and 10.5% (18/170) of the isolates, respectively. The distribution of MRSA, the inducible clindamycin resistance phenotypes and the presence of mecA, ermA, ermB, ermC and mrsA/B genes among the isolates from outpatients and inpatients are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Approximately 53% (90/170) of the isolates carried at least one of the erm (A,B,C) and/or mrs (A/B) genes. In this study, a significant correlation (P < 0.05) was observed between the presence of the mec (A) gene with the carriage of erm and mrs genes (Table 4). The rate of the erm and mrs resistance genes associated with mec (A) was 76/8% (53/69)

| Type of Isolate | Rate of Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolates, No. | AK | GM | CD | E | CIP | T | TS | VA | LZD | |

| Inpatient | 145 | 48 (33) | 59 (40.5) | 69 (47.5) | 81 (55.8) | 75 (52) | 94 (65) | 46 (32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Outpatient | 25 | 4 (16) | 9 (36) | 9 (36) | 13 (52) | 8 (32) | 12 (48) | 8 (32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 170 | 52 (30.5) | 68 (40) | 78 (45.8) | 94 (55.5) | 83 (48.8) | 106 (63) | 54 (31.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Antibacterial Resistance Pattern of S. aureus Isolates Recovered from Outpatients and Inpatients in Kerman, Irana

| Isolates Patients | Isolates, No. | MRSA | D-test positive | mec(A) | erm(A) | erm(B) | erm(C) | mrs(A/B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient | 145 | 82 (56.5) | 19 (13) | 63 (43.5) | 18 (12.5) | 6 (4.5) | 31 (21.5) | 11 (7.6) |

| Outpatient | 25 | 7 (28) | 2 (8) | 6 (24) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 7 (28) |

| Total | 170 | 89(52.5) | 21 (12.5) | 69 (39.5) | 19 (11) | 6 (3.5) | 35 (20.5) | 18 (10.5) |

Distribution of MRSA, Inducible Clindamycin Resistance (D-Test Positive), and mec(A), erm(A), erm(B), erm(C) and mrs(A/B) genes among S. aureus isolates from outpatients and inpatients

| Pattern of Resistance Genes | Number of Isolates | |

|---|---|---|

| Outpatient | Inpatient | |

| D-test positive | 1 | 2 |

| mec (A) | 2 | - |

| mec(A) + D-test positive | - | 5 |

| D-test positive + erm(C) | 1 | - |

| mec(A) + erm(C) | 2 | 9 |

| mec(A) + erm(A) | - | 4 |

| mec(A) + erm(B) | - | 2 |

| mec(A) + mrs(A/B) | - | 4 |

| mec(A) + D-test positive + erm(A) | - | 1 |

| mec(A) + D-test positive + erm(C) | - | 2 |

| mec(A) + erm(A) + erm(C) | 1 | 9 |

| mec(A) + erm(C) + mrs(A/B) | 1 | 4 |

| mec(A) + D-test positive + erm(B) + erm(C) | - | 1 |

| mec(A) + D-test positive + erm(A) + erm(B) | - | 1 |

| mec(A) + D-test positive + erm(C) + mrs(A/B) | - | 2 |

| mec(A) + erm(A) + erm(B) + erm(C) | - | 1 |

| Total | 8 | 47 |

Distribution Co-Existence of mec(A), Inducible Clindamycin Resistance (D-Test Positive), and erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), and mrs(A/B) Genes Among Clinical Isolates of S. aureus.

5. Discussion

Based on the results of this study, the prevalence of S. aureus resistance to macrolides and lincosamides was high in Kerman, Iran. In recent years, the number of infections with S. aureus, especially MRSA macrolide and lincosamide-resistant isolates have increased in our country and worldwide (4, 6, 12-16). In the present study, the highest resistance rates were observed for tetracycline, erythromycin, and ciprofloxacin, respectively (Table 2), which was somewhat similar to a study in Tehran, Iran, which showed the highest antibiotic resistance against co-trimoxazole, erythromycin, and tetracycline, respectively (17). The mec(A) gene was detected in 24% (6/25) and 43.5% (63/145) of isolates from outpatients and inpatients, respectively. In this study, a significant correlation (P < 0.05) was observed between the presence of the mec(A) gene and macrolide- and lincosamide-resistance genes in S. aureus isolates. In contrast to Schmitz et al., who reported that the macrolide-resistance gene was only detected in methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) (18), our results showed that macrolide-resistance genes, including erm(A,B,C) and mrsA/B were associated with the mecA gene and MRSA isolates. These results suggested that there is probably a correlation between the mecA gene and others, such as macrolide-resistance genes, in S. aureus isolates in Kerman, Iran. Similar to other studies (3, 6), the MRSA isolates were resistant to five or more classes of antibiotics. According to some previous reports and our results, MRSA isolates are commonly resistant to many antibiotics, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones (6, 15, 16). In the present study, all isolates from both outpatients and inpatients were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid; these results are in agreement with Zmantar et al. in Tunisia and with Navidinia and Shahmohammadi et al. in southwest Iran (6, 12, 17). Therefore, vancomycin and linezolid are still the most active agents against MRSA isolates. In contrast to our findings, in a study in Kerman, Iran by Shakibaie et al. prevalence of vancomycin intermediate resistant S. aureus 88.3% were reported by disk diffusion method, but according to CLSI guidelines, resistance to vancomycin must be screened with the agar dilution method, not the disk diffusion method. For this reason, Shakibaie et al.’s report is unreliable (4, 19). We found that the rate of resistance in is high in outpatient isolates. This finding supports the prediction that in the near future, many antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, and erythromycin, will probably not be able to be used as agents for the empirical therapy of community-acquired infections. In the present study, 12.5% of isolates demonstrated inducible clindamycin resistance. In 2012, Mansouri et al. reported inducible clindamycin resistance in 8.64% of S. aureus isolates in Kerman. These results confirmed the increase of inducible clindamycin-resistance isolates to 12.5% in 2015 in Kerman (20). In this study, the resistance genes, including erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), and msr(A/B), were detected in 11%, 3.5%, 20.5%, and 10.5% of erythromycin and clindamycin-resistant isolates, respectively. These results were similar to those of Goudarzi et al. in Khorramabad, Iran (21). Also, the erm and msr genes have been reported in countries such as Denmark, the United Kingdom, and Tunisia (12). In Denmark and Tunisia, erm(A) and erm(B) were the most common erythromycin and clindamycin-resistance genes, respectively, but in our study, erm(C) was the most common. Erythromycin and clindamycin-resistant genes were not detected in 44 (46%) of the isolates that showed resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin in the present study, which is similar to Zmanter et al.’s investigation, which found no correlation between molecular and phenotypic methods for the detection of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance (12, 22, 23). This difference may be explained by the heterogeneous nature of erythromycin resistance, or it may be due to the loss of small plasmids that carry erm and msr genes (12, 22, 23).

5.1. Conclusion

The high prevalence of macrolide- and lincosamide-resistant genes found in isolates from nosocomial and community infections in Kerman, Iran, may be due to the transfer of resistance genes among isolates. As the macrolide-resistance genes are located on mobile genetic elements, horizontal transmission from resistant to susceptible isolates is unavoidable. Therefore, knowledge about susceptibility patterns may provide crucial information for controlling the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance.