1. Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the major cause associated with otitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, respiratory tract infections, and pneumonia, as well as an outstanding cause of meningitis, bacteremia, and many other infections (1-4). In world, 1,000,000 child deaths occur each year from pneumococcal disease. This occurs mainly in developing countries (5-7).

S.pneumoniae was susceptible to beta lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, cephalosporin, and carbapenem (8). Currently, the overall increase in antibiotic resistant S. pneumoniae has become a serious problem (9, 10). In recent decades, a worrying increase of resistance to erythromycin in Asian countries (72.7%), with the highest rates reported in China (96.4%), Taiwan (84.9%), and Korea (80.6 %) (11, 12).

For the first time in 1967 a clinical isolate of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae was outlined; the isolate was obtained from a patient in Australia (8, 9). During the same decade, increasing penicillin-resistant isolates have been found in several parts of the world (8, 13, 14). Epidemiological studies can play a crucial role in identification of the antimicrobial resistance. It also improves antibiotic prescribing by supervision and support of clinical practices, especially diagnostic and treatment strategies (15). Furthermore, by screening changes in resistance schemas and the spread of principal resistance phenotypes around the world, these studies enable us to perform interposition strategies and to standstill the spread of such isolates. An increase in disease caused by S. pneumoniae due to widespread emergence of antimicrobial resistance has been emerged in many countries from the 1990’s (16). Although, the penicillin-resistant pneumococcus was first identified by Hansman et al. in 1967. Their first resistant isolate was recognized in Australia from the sputum of a patient with hypo gammaglobulinemia. Afterwards, resistant strains were recognized in Australia (17).

The reported rate of penicillin-resistant pneumococci in Asia is 70% - 78% (18). Penicillin resistance in S. pneumoniae is the result of an alteration in the penicillin target position, which are penicillin-binding proteins [PBPs (1A, 1B, 2A, 2X, and 2B)]. PBPs are involved in peptidoglycan synthesis, the relatively little variation of the genes, which contribute in the encoding of these proteins with low tendency to beta lactam antibiotics. In clinical isolates, modified pbp2b has a major role in penicillin-resistance. Successions in the pbp2b transpeptidase domain are associated with resistance to penicillin and amoxicillin (19-21).

2. Objectives

This study was a cross sectional. In the present study, we describe the prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and identification of the pbp2b gene of S.pneumoniae isolates at specimens of several general hospitals in Tehran, the capital of Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains

This study is a cross sectional descriptive study. A total of 73 S. pneumoniae isolates obtained from various clinical specimens from hospitals in Tehran from September 2012 to July 2015. Identification of S.pneumoniae isolates were accomplished by phenotypic tests such as hemolysis, Gram staining, bile solubility, and susceptibility to optochin disc (MAST, UK). The S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 strain was used as quality control. Bacteria were cultured on 5% sheep blood agar (MERCK, Germany) in a moistened atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. A medium containing skim milk, tryptone, glucose, and glycerin (STGG) was used for the storage of bacteria at -700°C.

3.2. Antimicrobial Agents

The antibiotic susceptibility of S. pneumoniae isolates were examined for 8 antibiotics as follows; penicillin, erythromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazol, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ofloxacin, meropenem, and vancomycin, which were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, UK.

3.3. Susceptibility Test

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests of pneumococcal isolates were performed by the broth microdilution method according to guidelines of the clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) (22). The following concentrations for the antimicrobials were used: 32 µg/mL, 16 µg/mL, 8 µg/mL, 4 µg/mL, 2 µg/mL, 1 µg/mL, 0.5 µg/mL, 0.25 µg/mL, 0.12 µg/mL, and 0.06 µg/mL. The microplates were incubated at 35ºC in ambient air for 20 to 24 hours. We used 2 separate interpretive breakpoints for meningeal and non-meningeal isolates to penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime. For non-meningitis isolates, an MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL for penicillin and an MIC ≥ 4 μg/mL for ceftriaxone and cefotaxime were considered resistant. For meningitis isolates an MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/mL for penicillin and an MIC ≥2 μg/mL for ceftriaxone and cefotaxime were considered resistant (23). S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 strain was used as a quality control strain for susceptibility testing.

3.4. PCR and Nucleotide Sequencing

Extraction of DNA from pneumococcal isolates was done using a high pure PCR template preparation kit (Roche; Germany). Amplification of the pbp2b gene was performed by specific primers (Table 1).

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5’→3’) | Product, Length, bp |

|---|---|---|

| pbp2b-F | CTTTGTCCCAGGTTCGGTTG | 320 |

| pbp2b-R | CCCAAGCCATATTCGCCAAA | |

| cpsA-F | GCAGTACAGCAGTTTGTTGAACTGACC | 160 |

| cpsA-R | GAATATTTTCATTATCAGTCCCAGTC |

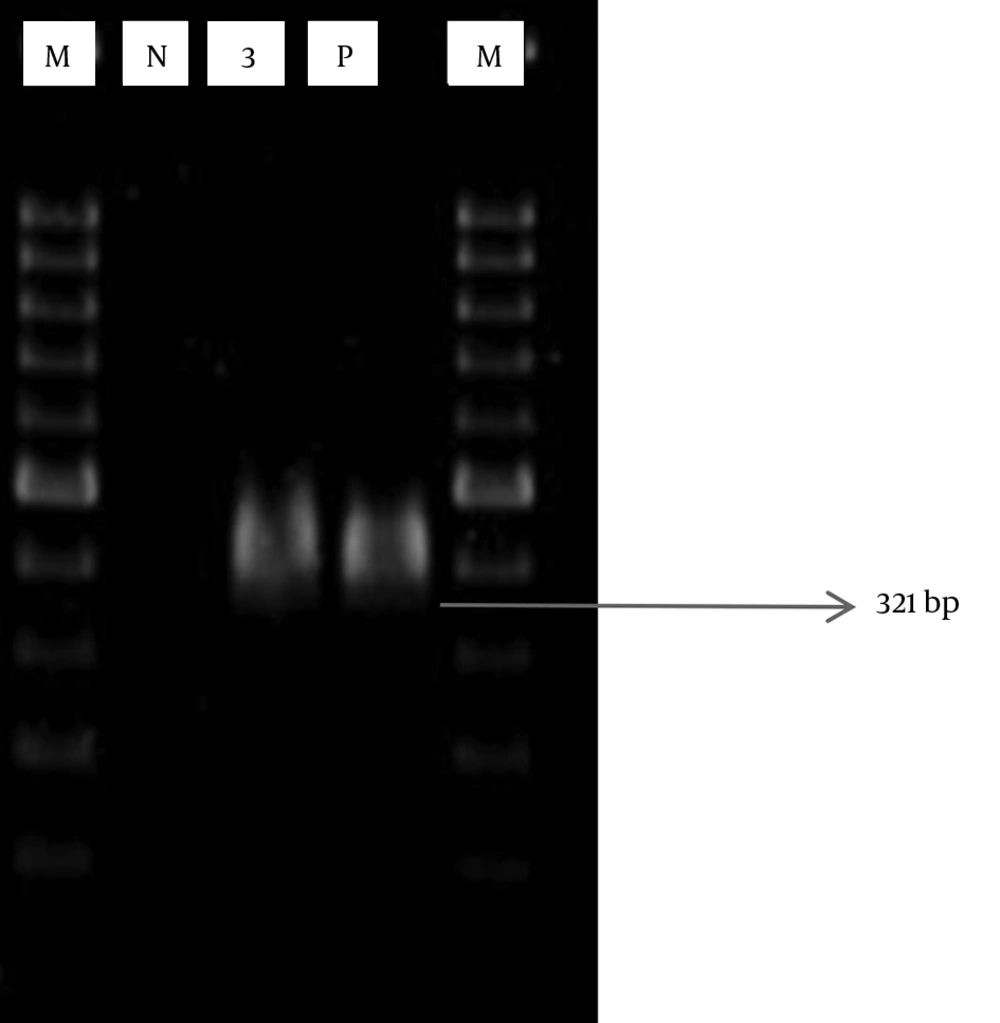

PCR assay was performed in a total volume of 25 μL containing 12.5 μL PCR master mix (Sinagen; Iran), 1 μL template DNA, 1 μL forward primer (50 pmol/μL), 1 μL reverse primer (50 pmol/μL), and 9.5 μL distilled water. The PCR cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation of 95°C for 5 minutes followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 40 seconds, and then a final extension of 72°C for 7 minutes (Eppendorf; Germany). PCR products were visualized by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and red safe staining (Intron; USA). Sequencing of the products were carried out by Bioneer Corporation, South Korea after purification. DNA sequences were aligned using multiple sequence alignment in NCBI.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

We conducted the statistical analysis with the chi-squared test and SPSS (version 18) when appropriate. Differences were considered significant when p was < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Collection of Pneumococcal Isolates

A total of 73 non-duplicate S. pneumoniae isolates were prospectively collected from patients with pneumococcal infections. Strains were isolated from the following sources: cerebrospinal fluid [CSF; n = 15 (20.5%)], blood cultures [n = 13(17.8%)], sputum [n = 15 (20.5%)], BAL [n = 6 (8.2%)], eye [n = 5 (6.8%)], nasal [n = 3 (4.1%)], and other body sites (brain abscess, joint fluid, throat, abdominal fluid, ear,) [n = 16 (21.9%)]. Pneumococci were isolated from individuals in the following age groups: ≤ 18 years [n = 28 (38.4%)] and > 18 years [n = 45 (61.6%)]. Among all patients, 38.4% were males and 32.9% were females (no data on the sex of the patients were available for 28.8% of the patients).

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

The susceptibilities of the 73 S. pneumoniae isolates are shown in Table 2. According to the revised CLSI breakpoints for parenteral penicillin (resistant [R], MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL for nonmeningeal isolates and MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/mL for meningeal isolates), prevalence rates of penicillin resistance were 16.43% and 4.1% in meningeal and nonmeningeal isolates, respectively. Overall, 20.5% and 1.4% of the isolates were penicillin resistant and penicillin intermediate, respectively.

aValue are expressed as percent.

bThe Streptococcus spp. isolate is susceptible to vancomycin, for which resistance has not been documented and for which only “susceptible” interpretive criteria exist in CLSI 2014.

For ceftriaxone and cefotaxime (resistant [R], MIC ≥ 4 μg/mL for nonmeningeal isolates and MIC ≥2 μg/mL for meningeal isolates), prevalence rates of cefotaxime resistance were 16.43% and 26.02% in meningeal and nonmeningeal isolates, respectively. Ceftriaxone resistance was 13.69% and 17.8% in meningeal and nonmeningeal isolates, respectively. Sixty-one (83.6%) S. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to erythromycin and only 6 (8.2%) were susceptible. The susceptibility rates of S. pneumoniae isolates to ofloxacin, vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazol, and meropenem were 95.9%, 93.2%, 61.6%, and 52.1%, respectively.

4.3. PCR Amplification of Resistance Gene

Penicillin-resistant and penicillin-intermediate strains were isolated from the following sources: blood cultures [n = 8 (50%)], CSF [n = 4 (25%)], thrush [n = 2 (12.5%)], and each eye sample, and other body sites [n = 2 (12.5%)].

The pbp2b gene was successfully amplified by PCR (Figure 1). Out of 15 penicillin-resistant isolates, the pbp2b gene was identified in 12 (80%) isolates.

Only 1 isolate was observed penicillin-intermediate that detects the pneumococcal pbp2b gene.

4.5. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this manuscript have been submitted to the GenBank sequence database and assigned accession no. KT758057 and KU550060.

5. Discussion

Over the recent years, antimicrobial resistance among isolates of S. pneumoniae has been disseminated throughout the world. The prevalence of penicillin-resistant pneumococcus strains has been gradually increasing. Penicillin-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (PRSP) is now distributed worldwide and the distribution appears to be increasing rapidly. Furthermore, resistance seems to be expanding to include multiple antimicrobial agents (24-26).

In this study, we explained the characteristics of S. pneumoniae isolates from September 2012 to July 2015 in several general hospitals in Tehran, the capital of Iran. In the present study, the rate of penicillin non-susceptible pneumococci was 21.9%.

This situation may result from the common use of penicillin in older children. Furthermore, according to previous studies, it has been shown that Asians countries have the highest level of antimicrobial resistance in the world (27). Among the European countries, Spain and France have the highest rates of antimicrobial resistance (28, 29).

In our study, the incidence of penicillin-resistant isolates was 20.5%, which showed an increase with age. This situation may result from the common use of penicillin in older children. This is higher than 4% from Sweden (30), 7.2% from Germany (31), 7.8% reported from India (32), but less than 36.9% from Spain (33), 27.95% from South Korea (34), 22.8% from France (35), with the least being 94.5% reported from Hamadan, Iran (36).

Others findings included, the resistance rates of S. pneumoniae to cefotaxime and ceftriaxone was 42.5 and 31.5, respectively. This result for cefotaxime is less than 88% from US (37) and 54.3% from Japan (38), with ceftriaxone being 45% from Taiwan (39) but higher than 7% and 9% from Alaska (40) and 20.7% from Korea (41). The outcome from multitude of studies have demonstrated that notwithstanding the decrease in the consumption of antibiotics, the resistance to numerous antibiotic agents is yet increasing (42).

In our study, antibiotic resistance is higher in isolates from patients older than 18-years of age. One major cause of antibiotic resistance in this age group may be the increased antibiotic consumption. It was previously shown that the number of male patients was significantly greater than that of female patients (11).

In this study it was observed that most PRSP isolates have been isolated from patients with meningitis; and most PRSP isolated bacteria were obtained from blood cultures and CSF specimens. Furthermore, previous studies showed that most S. pneumoniae strains are isolated from blood and CSF samples (43). In the present study, according to database distribution, the ages of the patients determined that more than half of the patients were adults. The rate from adults over the age of 18 years, were 61.6%. Our results are different from other studies (11, 27); but Reinert et al. reported infections caused by pneumococci occurred often in older patients (28) where as S. pneumoniae was mostly isolated from male patients than female patients. This difference in the present study could be related to the collected samples from the general hospitals. If samples were collected from only children’s hospitals, this percentage could be different.

Principally, a microbial test and PCR were used to identify S. pneumoniae. PCR assays were performed to confirm phenotypic test results (44). Overall, the studies stated that the advantage used in methods based on DNA technique in the recognition and determination of resistance genes in PRSP as well as resistance genes for other groups of antimicrobial agents. It can be a lot of information regarding the class of resistance mechanism with the use of molecular techniques (45, 46). In our study all examined strains, were resistant to penicillin (R; with MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL for nonmeningeal isolates & MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/mL for meningeal isolates and Intermediate [I]; with MIC = 4 μg/mL for nonmeningeal isolates).

The prevalence of PRSP was 81.81% among the patients with meningitis, which is higher than other groups. These types of antibiotic resistances have been reported by Enright et al., however, the prevalence rate reported in Spain (45.5%) was less than our study (47).

PRSP do not produce beta-lactamases. Previous researches have obviously pointed out that the three penicillin--binding proteins (PBP 1a, 2x and 2b) are important for the resistance to beta-lactams. Variations in the conserved elements in pbp2b are related to resistance to penicillin. The low-affinity versions of PBPs are the outcomes of acquiring genes from other species, for example streptococcus viridans and recombination of the genes coding for these proteins (48-50). It has been suggested that the mutations in pbp2b is associated with reduced susceptibility to penicillins and carbapenems in the S. pneumoniae isolates (51).

The pbp2b gene was not detected in 3 resistant pneumococci in our study; the source of resistance to penicillin in these strains can be caused by mutations in other genes that code the residual PBPs. In the present study, PRSP isolates containing the pbp2b gene were the most frequently found. Habibian et al. (2013) reported that the pbp2b gene was found in 4 of the total 50 samples (46). Kotevska et al. (2009) reported that of the total 40 resistant/intermediate resistant S.pneumoniae, in 22 genes pbp2b and/or pbp2x were verified (18). According to the findings, the pbp2b gene can play a role of fundamental importance in the resistance of S. pneumoniae. Resistant pneumococcal isolates are more common amongst the older population, which is significant in the process of spreading PRSP clones around the world. It can be concluded that PRSP isolates can be a common cause of bacterial meningitis in Iran. Therefore, suggests a useful impact of diversifying the use of antibiotics. Modify heterogeneity in antibiotic use, which several antibiotics are taken in a rotation against taking just 1 antibiotic such that isolates resistant to 1 antibiotic are killed when the subsequent antibiotic is taken.