1. Background

HIV is mainly a blood-borne infection, which is transmissible through sexual contact. Researchers have introduced various HIV infection risk factors, including unsafe sex, men who have sex with men (MSM), polygamy, female sex workers (FSWs) and their clients, sexually transmitted diseases, substance use, whether injection drug use (IDU) or non-injection illicit drug use (NIDU), maternal HIV infection, being a refugee, and imprisonment (1-10). With the increased spread of HIV infection to the general population from high-risk individuals to other persons, there is a growing need for early detection, which can itself lead to the prevention of newly acquired cases. Early detection of new HIV cases is critical in regions with low education and severe health resource constraints.

Hospital admission could be the momentum for voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) and finding new cases of HIV infection, and identifying previously undiagnosed cases of HIV infection (11-14). In 2004, approaches to the application of HIV counseling, testing, and referring were proposed by the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (9). Nonetheless, in 2007, WHO/UNAIDS guidelines recommended HIV testing as a part of the standard medical care (15). This guideline clearly states that provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling in concentrated epidemic areas should not recommend HIV testing and counseling to ALL people referring to all health facilities. However, selected health facilities in concentrated epidemics should be treated differently, and populations most at risk for HIV infection transmission in these settings need to have access to counseling, testing, and referral (15).

Iran is now at a concentrated level for HIV infection, and although a national guideline for the management of HIV/AIDS patients currently exists, this guideline does not explicitly include a recommendation for in-hospital HIV counseling and testing (7, 16).

There is limited evidence on the true prevalence of HIV positive referrals (both known and new cases of HIV infection) to hospital settings of Iran. However, it is evident that the use of traditional risk factors as a guide for HIV testing in the hospital setting may not be feasible because of perceived stigma and discrimination, concerns about the confidentiality of results, poor attitude, cultural barriers, or limited available time of healthcare providers (8, 17-23). In this situation, seropositive HIV patients may be lost; thus, there should be other predictors in history and physical examinations and hospital presentation of referred patients, which could be asked in the routine history taking in hospitals.

2. Objectives

Hospitals should provide the situation for VCT. Besides, healthcare providers should decide whether to order HIV test for patients or not. In other words, specific clinical and demographic factors associated with HIV-positive status in hospitalized patients has not been incorporated into testing practice, which underlines the importance of developing a systematic approach to testing the admitted patients for HIV infection in Shiraz hospitals. As a result of this, the predictors of HIV-positive test results in a general hospital in Shiraz are investigated in this study.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting

In this case-control study, records of all admitted patients who requested HIV testing during 12 months in 2017 were assessed. The record number of patients with positive HIV test results was extracted through Hospital Information system (HIS) to use the anonymous clinical data for research purposes in a university-affiliated general hospital of most-at-risk HIV-positive patients in Shiraz. Shiraz is the capital of Fars province, which is the largest province in southeast of Iran.

Opt-out provider-initiated testing and counseling HIV test for almost all admitted patients was requested after obtaining written informed consent. All patients admitted for one day or more with a requested HIV test and complete patient records during the study period were included. Outpatient cases were excluded (due to the lack of registered records). Records with incomplete demographic, clinical, and behavioral data were excluded.

3.2. Data Collection

Records of HIV-positive patients were evaluated, and relevant data were collected within a data collection form. This form included demographic data (i.e., age, sex, education, nationality, place of residency, job and, insurance status, and readmission), clinical data (i.e., new case or known case, living status on discharge, physical examination, presentation on admission, TB status, and CD4 number), and behavioral data (i.e., the route in which the HIV infection has been acquired). Due to the first presentation’s diversity, the cases were divided into the two categories of probably infectious causes (e.g., cough, fever, lymphadenopathy, rash, and jaundice) and other non-infectious presentations (e.g., fatigue, weight loss, body pain). In the case of two or more concomitant presentations, infection was considered positive. For each HIV-positive case, at least one control from the same ward was randomly (using the random number generator software) selected from the list of negative HIV test results. More control subjects were selected compared to cases to increase the power of the study. The same data were collected for the control group. One hundred control subjects were selected. Excluding three incomplete records, 97 control subjects were finally assessed. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee (ethical committee code: 95-01-62-12889) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive and analytical methods through SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We used the chi-square test to compare qualitative variables and independent samples t-test and ANOVA for continuous variables. Independent variables with a P-value < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were entered into the logistic regression model using stepwise forward selection. These variables included sex, age, education, hepatitis, opium addiction, iv drug use, prison history, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Statistically significant predictors were selected, and odds ratios were derived for these predictors. Age was divided into eight categories (every ten years); the first category was under 20 and the last one over 80 years.

Based on the best-fitted model of logistic regression, the probability of positive HIV test results was estimated for each participant according to the risk factors, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) to measure how well the predictors can distinguish positive HIV test results was estimated. Sensitivity, specificity, and risk scores (based on the best fitted logistic regression model) were assessed. The significance level was set at 0.05.

4. Results

During the study period, 7333 HIV tests were requested by the physicians. Out of these, 77 were HIV positive (one percent), and 19 patients were diagnosed for the first time (2 out of each 1000 test).

Most HIV-positive patients were male (55 = 71.4%). The mean age of the HIV-positive patients was 41.5 ± 9.5 years. Other characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. None of the participants in the control group had tuberculosis, positive history of imprisonment, or IV drug abuse. The risk factor evaluations of the participants are shown in Table 2. Mean ± SD (median) of CD4 in the HIV group was 205 ± 215 (139).

| Characteristics | HIV Case | Control | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 77 | 97 | |

| Known* | 58 | ||

| New** | 19 | ||

| Age mean ± SD | 49.83 ± 20.1 | 0.001 | |

| Known | 40.8 ± 9.6 (39) | ||

| New | 43 ± 9 (45) | ||

| Sex | 0.81 | ||

| Male | 68 (69.8) | ||

| Known | 42 (72.4) | ||

| New | 13 (68.4) | ||

| Female | 29 (30.2) | ||

| Known | 16 (27.6) | ||

| New | 6 (31.6) | ||

| Education | 0.026 | ||

| Illiterate | 15 (22.4) | 37 (40.2) | |

| Educated | 52 (77.6) | 55 (59.8) | |

| Nationality | 0.08 | ||

| Persian | 68 (89.5) | 93 (95.9) | |

| Afghan | 8 (10.5) | 3 (3.1) | |

| Living status on discharge | 0.06 | ||

| Live | 56 (72.7) | 82 (84.5) | |

| Death | 21 (27.3) | 15 (15.5) | |

| Place of residency | 0.4 | ||

| Urban | 65 (86.7) | 79 (81.4) | |

| Rural | 10 (13.3) | 18 (18.6) | |

| Insurance | 0.51 | ||

| Yes | 66 (85.7) | 84 (86.6) | |

| No | 11 (14.3) | 13 (13.4) | |

| Job | 0.7 | ||

| Unemployed | 6 (8) | ||

| Known | 4 (7.5) | ||

| New | 2 (15.8) | ||

| Employed | 44 (57) | ||

| Known | 33 (62.3) | ||

| New | 11 (57.9) | ||

| Retired | 8 (10) | ||

| Known | 2 (3.8) | ||

| New | 0 | ||

| Housekeeper | 19 (25) | ||

| Known | 14 (26.4) | ||

| New | 5 (26.3) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

b*, Known, known cases tested again for HIV; **, new, first time detection.

| Risk Factors/Behavior | HIV Case | Control | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette and/or Water pipe* | 0.018 | ||

| Yes | 31 (40.8) | 23 (23.7) | |

| No | 45 (59.2) | 74 (73.6) | |

| Alcohol | 0.18 | ||

| Yes | 2 (2.7) | 8 (8.2) | |

| No | 73 (97.3) | 89 (91.8) | |

| Opium addiction | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 48 (64) | 22 (22.7) | |

| No | 27 (36) | 75 (77.3) | |

| IV drug use** | 0.005 | ||

| One time | 6 (9) | 0 | |

| More than one time | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| No | 60 (89.6) | 97 (100) | |

| Imprisonment history | 0.015 | ||

| Yes | 5 (6.6) | 0 | |

| No | 71 (93.4) | 97 (100) | |

| Hepatitis coinfection | < 0.001 | ||

| Hepatitis B | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1) | |

| Hepatitis C | 24 (31.6) | 0 | |

| Hepatitis B and C | 4 (5.3) | 0 | |

| No | 46 (60.5) | 96 (99) | |

| Operation history | 0.86 | ||

| Yes | 22 (28.9) | 26 (26.8) | |

| No | 54 (71.1) | 71 (73.2) | |

| Transfusion history | 0.30 | ||

| Yes | 13 (17.3) | 13 (13.4) | |

| No | 62 (82.7) | 84 (86.6) | |

| Tuberculosis*** | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 8 (10) | 0 | |

| No | 69 (90) | 97 (100) | |

| Route of transmission | |||

| Sexual | 18 (23) | ||

| IV drug | 39 (51) | ||

| Other/not specified | 6 (8) | ||

| No data available | 14 (18) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

b*, Current cigarette and/or water pipe user; **, lifetime IV drug use; ***, on anti- TB treatment

Logistic regression results (for HIV positive/negative test results) based on the stepwise forward method using best predictors (predictors that were important, including gender, hepatitis, opium addiction, and age) are described in Table 3.

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% CI for EXP(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Gender (female) | 1.092 | 0.449 | 5.902 | 1 | 0.015 | 2.980 | 1.235 | 7.190 |

| Hepatitis coinfection (yes) | 3.034 | 0.783 | 15.002 | 1 | < 0.001 | 20.774 | 4.475 | 96.435 |

| Opium addiction (yes) | 1.898 | 0.447 | 18.041 | 1 | < 0.001 | 6.676 | 2.780 | 16.030 |

| Age | -0.511 | 0.101 | 25.703 | 1 | < 0.001 | 0.600 | 0.493 | 0.731 |

According to the logistic regression, after controlling the risk factors (i.e., hepatitis, opium addiction, and age) OR for positive HIV test result was 2.980 for women compared with men. Also, controlling the risk factors of the model (i.e., gender, opium addiction, and age) demonstrated that OR for positive HIV test results was nearly 21 for hepatitis-positive patients (hepatitis B and/or C) compared to negative ones. By controlling hepatitis, gender, and age, this study found that positive HIV test results were almost seven times more in opium-addicted patients than non-opium-addicted ones. Each 10-year increase in age corresponded with a 40% decrease in the chance of positive HIV test result after controlling the risk factors of the model (i.e., hepatitis, opium addiction, and gender).

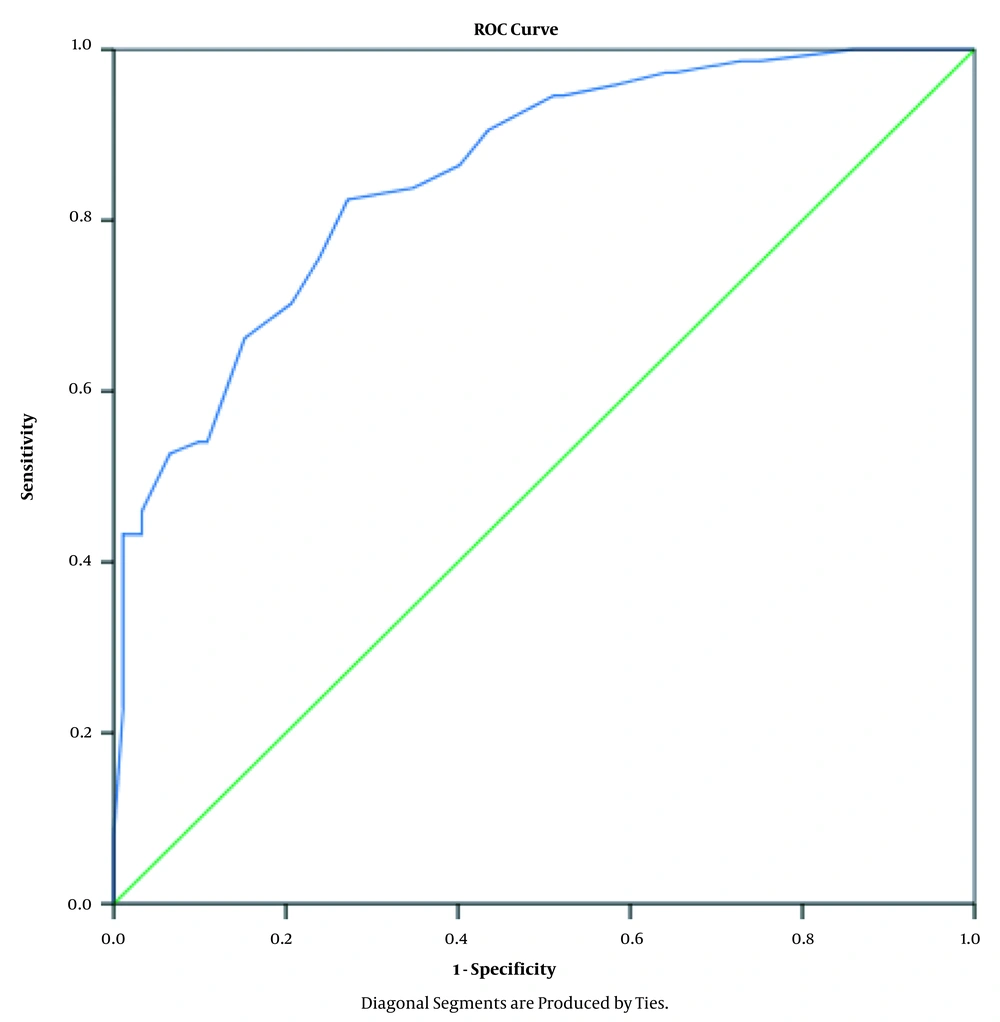

After performing the logistic regression on data and the estimation of the best-fitted model, the probability of positive HIV test results was estimated for each patient according to the risk factors, and the ROC curve was derived (Figure 1).

The AUC was 0.853 with 95% confidence interval (0.797 0.909) (Table 4), and the model was good (P < 0.001) for the prediction of positive test results (as a screening test for the detection of HIV-positive patients) in more than 85% of cases.

aThe test result variable(s): Predicted probability has at least one tie between the positive actual state group and the negative actual state group. Statistics may be biased.

bUnder the nonparametric assumption.

cNull hypothesis: true area = 0.5.

The sensitivity and specificity of different risk scores are presented in Table 5. To better distinguish HIV-positive patients, a point on the ROC curve should be selected which has the highest sensitivity and reasonable specificity. In Table 5, the cutoff point for risk score 0.2718 seems reasonable in which sensitivity is 90% with 60% specificity. The equation model for the calculation of the risk scores is:

P(Y = 1) = 1/{1 + exp-(B1X1 + B2X2 + B3X3 + B4X4)}

P(for screening of HIV test) = 1/{1 + exp-(1.09 (sex)+ 3.03 (hepatitis )+ 1.89 (addiction)+ -.511 (age)}

Risk score = 0.2718

| Positive If Greater Than or Equal tob | Sensitivity | 1-Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0000000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 0.0359638 | 1.000 | 0.924 |

| 0.0584433 | 1.000 | 0.859 |

| 0.0935411 | 0.986 | 0.750 |

| 0.1185344 | 0.986 | 0.728 |

| 0.1399653 | 0.973 | 0.652 |

| 0.1677270 | 0.973 | 0.641 |

| 0.1830364 | 0.959 | 0.587 |

| 0.2130532 | 0.946 | 0.522 |

| 0.2512982 | 0.946 | 0.511 |

| 0.2718083 | 0.905 | 0.435 |

| 0.3104118 | 0.865 | 0.402 |

| 0.3585413 | 0.838 | 0.348 |

| 0.3834209 | 0.824 | 0.272 |

| 0.4279503 | 0.757 | 0.239 |

| 0.4908962 | 0.703 | 0.207 |

| 0.5541773 | 0.662 | 0.152 |

| 0.5991746 | 0.541 | 0.109 |

| 0.6245113 | 0.541 | 0.098 |

| 0.6738154 | 0.527 | 0.065 |

| 0.7134988 | 0.459 | 0.033 |

| 0.7319197 | 0.432 | 0.033 |

| 0.7716860 | 0.432 | 0.022 |

| 0.8057889 | 0.432 | 0.011 |

| 0.8146013 | 0.419 | 0.011 |

| 0.8477019 | 0.378 | 0.011 |

| 0.8833969 | 0.365 | 0.011 |

| 0.9022581 | 0.338 | 0.011 |

| 0.9228554 | 0.324 | 0.011 |

| 0.9389075 | 0.311 | 0.011 |

| 0.9575346 | 0.230 | 0.011 |

| 0.9740474 | 0.081 | 0.000 |

| 1.0000000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

aThe test result variable(s): Predicted probability has at least one tie between the positive actual state group and the negative actual state group.

bThe smallest cutoff value is the minimum observed test value minus 1, and the largest cutoff value is the maximum observed test value plus 1. All the other cutoff values are the averages of two consecutive ordered observed test values.

5. Discussion

This study showed that without the explicit recommendation criteria for counseling and testing HIV in a hospital setting, only 1% of those tested were diagnosed with HIV infection, and only 0.2% represented definitively newly recognized infections. This detection rate is lower than comparable observational and interventional studies and implies a waste of money and efficiency reduction (6, 13, 24-26).

It is perceptible that around 25% of HIV-positive cases were newly detected. This result shows that case finding in a hospital setting is extremely critical and can have numerous advantages. These benefits include the possibility to immediately start providing care, referrals for follow-up care after discharge, and its consideration as a setting for effective HIV infection diagnosis in patients' family members (12). However, the findings reveal that the rates of non-effective HIV testing is actually high, and more explicit recommendations for the effective detection of new infections is strongly recommended. The significance of early detection of HIV-positive cases is subjected to the first target of 90-90-90 approval: successfully diagnosing 90% of all HIV-positive people (27). The presence and implementation of explicit recommendations for emergency department (ED) and admitted patients, and consequently, offering routine HIV infection counseling, testing, and referral have improved the detection of new cases (13, 26). However, even with the presence of these recommendation, low rates of HIV testing in ED and inpatient settings is still a problem which requires further consideration (13).

This recommendation could be for patients presented with a risk score higher than 0.2718 in our setting. According to the proposed equation, risk score could be calculated based on gender, hepatitis B and/or C infection, opium addiction, and age as independent variables.

As stated beforehand, besides tuberculosis, positive history of prison and IV drug abuse are the conventional risk factors for HIV positive test results; in this hospital setting, female gender, hepatitis B and/or C patient, opium addiction, and younger age significantly predicted positive HIV test results. It is essential not to miss opportunities for detecting new HIV-positive test results in hospital settings, which could be momentum for VCT. The presented model for calculating the risk score for HIV test recommendation in this study could be an attempt toward diagnosing individuals at an earlier stage of HIV infection. However, there is not adequate national evidence for missed opportunities for the detection of new cases in hospital settings, but in France, it has been shown that missed opportunity for the detection of new HIV cases in healthcare facilities is still unacceptably high (28).

This study highlights positive HBV and/or HCV test results as an essential predictive factor for HIV positive test results (29-31). This picture is due to similar routes of transmission of HBV, HCV, and HIV infection. The detection of these co-infected patients in a hospital setting may help physicians with appropriated diagnosis and monitoring of chronic viral hepatitis as well as adequately confronting chronic viral hepatitis in HIV-positive patients (30, 31).

Logistic regression highlighted the female gender as a predictive factor in the proposed model of risk assessment. Although the prevalence of HIV infection in men is far more than in women in Iran (32), the greater susceptibility of women to HIV infection has been reported, which highlights the implications for culturally accepted interventions targeted to preventive strategies (33-35).

However, IDUs is known to be a significant risk factor for HIV infection, but it is also known that NIDUs are at higher risk for HIV infection transmission (4). The present investigation showed that opium addiction could be a predictive factor for positive HIV test results. The situation, however, needs to be deliberated case by case. As in a study in Brazil, transactional sex and in Tehran, the rapid transition of inhaled opium to injected opiates were highlighted as the essential risks for HIV infection transmission in NIDU individuals (4, 34).

It is noteworthy that the nature of this study was limited to the evaluation of causal linkage of the studied factors, and prospectively designed studies are recommended. Also, it is essential to mention that due to zero TB patients in the control group, this variable could not be assessed in the logistic regression model; however, according to the WHO/UNAIDS recommendation, TB-infected patients should be tested for HIV (15).

5.1. Conclusions

Hospital admission could be an appropriate momentum for providing voluntary counseling and testing (VCT). Infection with HBV and HCV are risk factors for concomitant HIV infection, and additional tests should be offered, especially to these persons.