1. Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are frequent and constitute a significant health problem in almost all countries. Chlamydia trachomatis is one of the most common STIs globally that is the cause of a broad spectrum of human diseases. Conferring to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) reports, the prevalence of worldwide chlamydial infection has progressively increased over the last two decades, and there were 127 million new cases of Chlamydia in 2016 (1-3).

The C. trachomatis infection is often asymptomatic in women (about 75%) and can lead to chronic manifestations. Untreated chlamydial infections may cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, low birth weight, and infertility (4-6). It is noteworthy that the risk factors of C. trachomatis infection in women differ by setting and the existence of symptoms. The infection risk factors include age, inconsistent use of barrier contraception, prior sexually transmitted infection, low educational and socioeconomic levels, cervical infection, and polygamous marriage (6, 7).

An essential measure for the prevention and chlamydial infection control can be identifying women with asymptomatic or mild endocervical infections and those at increased risk for acquiring this infection (7, 8). The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends annual screening for C. trachomatis infection in all sexually active women younger than 25 years old. Moreover, women older than 25 years and all sexually active men at risk of the infection should also be screened (9).

The conventional laboratory diagnosis of C. trachomatis infection is made through cell culture or antigen detection. However, the gold-standard techniques for genital Chlamydia infection are now nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Recently, commercially available NAATs methods, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays with high sensitivity and specificity, have been widely used for detection of C. trachomatis infection (6, 10).

2. Objectives

Given the importance of identifying chlamydial infection among women in developing countries, this study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of endocervical C. trachomatis infection and related risk factors among women attending the Gynecology Clinic, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, East of Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population and Sampling Procedure

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 195 women attending the University Gynecology Clinic in Birjand, the capital of South Khorasan province, Iran, during 2018 - 2019. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Birjand University of Medical Sciences (IR.BUMS.REC.1397.88), and all enrolled subjects signed informed consent forms. The inclusion criteria were all women with asymptomatic and symptomatic of chlamydial infection attending the gynecology clinic. However, all pregnant and virgin women were excluded from the study. It is noteworthy that the socio-demographic and obstetric-related characteristics of subjects were collected using a structured questionnaire.

Endocervical sampling was performed in a lithotomy position using a sterile brush by the attending gynecologist. Samples were placed into 0.2 M sucrose phosphate buffer (2SP, pH = 7.2) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) containing 0.2% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and transported to the microbiology laboratory on ice (5).

3.2. PCR Assay

The cervical brushes were removed after vortexing, and the samples were used for further processing. According to the manufacturer, DNA extraction was performed using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche, Germany) from the samples.

In this study, C. trachomatis was detected by TaqMan real-time PCR method using GeneProof C. trachomatis PCR kit (GeneProof, Czech Republic). According to the manufacturer's instructions, the kit detects the cryptic plasmid multi-copy sequence and the 16S rRNA gene for C. trachomatis. This kit uses ready-to-use master mix contains uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG) and dUTPs eliminating contamination with amplification products. Briefly, thermal cycling conditions for real-time PCR assay were as follows: 37°C for 2 minutes and 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 seconds, 60°C for 40 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds. The signal was acquired at 60°C during each cycle. Amplification and PCR product detection were performed with the ABI prism 7500 real-time-PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were investigated with the Pearson chi-square and Fisher's exact tests, using SPSS (version 21), to assess the statistical significance of associations between potential variables. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

4. Results

A total of 195 women with a mean age of 33.91 ± 9.84 (ranging from 17 to 60) years were included in the study.

4.1. C. trachomatis Infection and Related Risk Factors

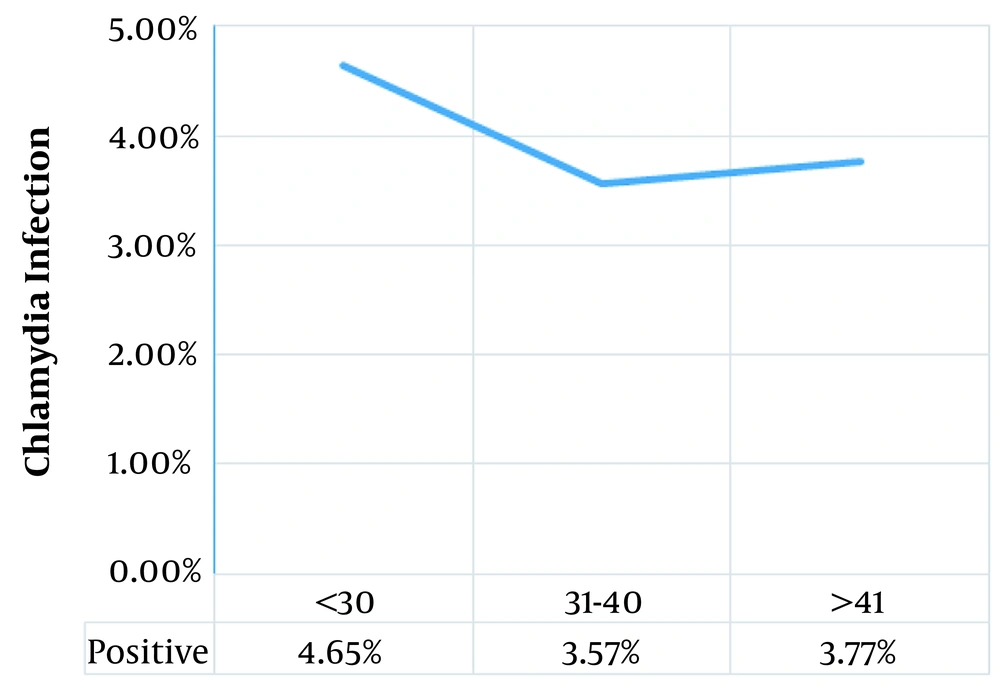

The prevalence of C. trachomatis infection was reported in 4.1% (8 patients) of the study population. The socio-demographic features of the women and their relationship with C. trachomatis infection are summarized in Table 1. Statistical analysis results revealed that there was no significant association between socio-demographic factors and C. trachomatis infection. It is noteworthy that although there was no statistically significant association between chlamydial infection and age, the highest rate of infection was in women less than 30 years old (Figure 1).

| Item/Status | Positive | Negative | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 34.00 ± 11.63 | 33.91 ± 9.80 | t = -0.03; df = 193; P = 0.98 |

| Occupation | χ2 = 1.06; df = 1; P = 0.60 | ||

| Housewife | 8 (4.6) | 165 (95.4) | |

| Employed | 0 (0) | 22 (100) | |

| Education | Fisher = 5.12; P = 0.07 | ||

| Illiterate | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | |

| High school | 4 (4.4) | 80 (95.2) | |

| College | 2 (2) | 97 (98) | |

| Dwelling | χ2 = 1.96; df = 1; P = 0.23 | ||

| Urban | 4 (2.9) | 136 (97.1) | |

| Rural | 4 (7.3) | 51 (92.7) | |

| Addiction | χ2 = 0.13; df = 1; P = 0.88 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | |

| No | 8 (4.1) | 184 (95.9) |

Abbreviation: df, degree of freedom.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Moreover, the associations of C. trachomatis infection with the clinical and obstetric risk factors are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The most common symptoms in the females were vaginal discharge (71.4%), lower abdominal pain (71.4%), dyspareunia (42.8%), and burning sensation (42.8%). It is noteworthy that C. trachomatis infection was associated only with a history of vaginal infection (P = 0.001). C. trachomatis infection was reported in 9.5% of cases with a history of vaginal infection vs. 0% in those with no history.

| Item/Status | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical symptom | χ2 = 0.53; df = 1; P = 0.68 | ||

| Yes | 7 (4.7) | 143 (95.3) | |

| No | 1 (2.2) | 44 (97.8) | |

| Physical examination | Fisher = 3.37; P = 0.14 | ||

| Genital ulcer | 2 (10) | 18 (90) | |

| Herpes lesions | 0 (0) | 40 (100) | |

| Normal | 6 (4.4) | 129 (95.6) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | χ2 = 0.17; df = 1; P = 0.84 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | |

| No | 8 (4.1) | 183 (95.9) | |

| History of antibiotic usage | χ2 = 1.23; df = 1; P = 0.39 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | |

| No | 8 (4.7) | 162 (95.3) |

Abbreviation: df, degree of freedom.

| Item/Status | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pregnancy | Fisher = 0.57; P = 0.80 | ||

| Without pregnancy | 1 (2.6) | 37 (97.4) | |

| 1 - 2 | 3 (3.5) | 81 (96.5) | |

| 3 | 4 (5.4) | 69 (94.6) | |

| History of abortion | χ2 = 0.12; df = 1; P = 0.63 | ||

| Yes | 2 (3.8) | 50 (96.2) | |

| No | 6 (4.2) | 137 (95.8) | |

| Type of delivery | Fisher = 0.59; P = 0.79 | ||

| Without delivery | 1 (2.4) | 41 (97.6) | |

| Vaginal | 6 (5.3) | 108 (94.7) | |

| Cesarean | 1 (2.6) | 38 (97.4) | |

| Preterm delivery | χ2 = 0.15; df = 1; P = 0.53 | ||

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 16 (94.1) | |

| No | 7 (3.9) | 171 (96.1) | |

| History of infertility | χ2 = 0.01; df = 1; P = 0.69 | ||

| Yes | 1 (3.7) | 26 (96.3) | |

| No | 7 (4.2) | 161 (95.8) | |

| History of vaginal infection | χ2 = 11.02; df = 1; P = 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 8 (9.5) | 76 (90.5) | |

| No | 0 (0) | 111 (100) | |

| Sexual activity | χ2 = 0.09; df = 1; P = 0.92 | ||

| Active | 8 (4.1) | 185 (95.9) | |

| Without intercourse | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

Abbreviation: df, degree of freedom.

5. Discussion

C. trachomatis infection is one of the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide, and women carry the significant burden of the disease. The WHO's most recent estimates indicate that in 2016 about 127 million new cases of C. trachomatis occurred globally. However, there is no detailed information on the incidence of chlamydial infection, especially in developing countries where routine laboratory diagnosis is unavailable (11-13).

The prevalence rate of C. trachomatis among the women was reported at 4.1% in our study. This finding was lower than many other reports in Iran (5, 7, 14, 15), and other developing countries, such as Ethiopia (18.9%), Brazil (10.7%), Serbia (15.4%), and India (23%) (1, 8, 12, 16), but higher than those reported in Jordan (3.9%), Nigeria (3.5%), and another study in Iran (2.4%) (6, 17, 18). Discrepancies in C. trachomatis infection rates among women in the studied populations could be explained in terms of age, ethnic group, socio-economic status, and lifestyle; the geographic areas, hygiene, and barrier contraception during intercourse, sexual behavior, sampling method, and the diagnostic techniques (1, 7, 8).

The results of our study showed that there was no significant association between socio-demographic factors and C. trachomatis infection. It is noteworthy that although there was no statistically significant association between chlamydial infection and age, the highest rate of infection was in women less than 30 years old. This finding is consistent with other studies (6, 18-20). These age groups all fall within the sexually active, explaining a higher prevalence of STIs among them (6, 20). However, it was not statistically significant in our study.

Finally, numerous epidemiological surveys for C. trachomatis in women have identified various associated risk factors for infection (14, 18). Interestingly, we found an association between a history of vaginal infection and an increased prevalence of C. trachomatis in women. This finding is comparable to those reported by others and suggests that a history of vaginal infection may be the major risk factor for chlamydial infection. Kayiira et al. showed that over 36.96% of the participants with current genital C. trachomatis had a history of genital infection compared to 2.9% of participants in the non-exposed group (21). Nevertheless, the fact that the sample size did not achieve statistical power can explain the lack of association between C. trachomatis infection and other clinical-obstetric risk factors in our study.

5.1. Conclusions

Given the relatively significant incidence of C. trachomatis infection among women, our findings highlight the status of routine screening and early diagnosis of C. trachomatis to control the infection. However, further studies with a larger sample size and more focused on different high-risk groups are needed to prevent and control the infection. Analysis of the results showed an association between a history of vaginal infection and an increased prevalence of C. trachomatis in women, but further studies are needed to assess the correlation between different risk factors and C. trachomatis infection.