1. Background

The development of a series of new chemotherapeutic and biological agents has significantly reduced cancer-related mortality (1). However, these treatments are frequently associated with severe immunosuppression, leading to a higher risk of infection. Neutropenia remains the most commonly observed adverse outcome of anti-neoplastic chemotherapy, and infections of all types have increased in patients with neutropenia (2). Therefore, appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy is crucial for patients with febrile neutropenia (FN) and is associated with improved outcomes (3-5). Since there are variations among institutions and geographic areas, specific antimicrobial treatment regimens should be based on local epidemiologic data (3, 6).

Local epidemiological profiles of infecting microorganisms in hospitals commonly vary. Consequently, providing appropriate antimicrobial regimens for FN patients relies on detecting these local changes in a timely manner (7).

2. Objectives

This retrospective study was conducted to document the bacterial spectrum and susceptibility patterns of the pathogens isolated from blood cultures, which are directly suggestive of true pathogens. This will enable us to provide a reliable empirical treatment strategy for hospitalized FN patients in the setting of extensive resistance.

3. Methods

Hospitalized FN patients with positive blood cultures at the Bahrain Oncology Center between January 2019 and September 2021 were included in this study. This study retrospectively reviewed the medical records through the electronic hospital information system for all clinical and microbiological data. Blood culture results were collected as the sole microbiological data to eliminate the possibility of colonization as much as possible. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Hamad University hospital, Al Sayh, Bahrain (22-480).

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients with hematological or solid organ malignancies who experienced FN and had positive blood cultures were included.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients under 18 years of age, those with fungemia, or those with contaminated blood cultures were excluded. Contamination was defined as the isolation of usual skin colonizer gram-positive microorganisms from at least one set of two or more blood cultures, along with the absence of clinical findings indicating infection with the isolated microorganism.

Febrile neutropenia was defined as: (1) Absolute neutrophil count ≤ 0.5 and those expected to be ≤ 0.5 within 2 days; (2) a single oral temperature measurement of ≥ 38.3 °C (101 °F) or a temperature of ≥ 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) sustained over 1 hour.

3.3. Severity Status of the Patients

The severity status of the patients was classified using the quick sequential organ failure assessment (qSOFA) score (8). Patients were categorized into two groups as follows: Mild patients (qSOFA < 2) and critical patients (qSOFA ≥ 2). Additionally, septic shock was defined as persisting hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg or higher despite adequate volume resuscitation (9).

3.4. Microbiological Procedure

Blood cultures were obtained from both central (if in place) and peripheral lines; otherwise, two peripheral samples were collected. Blood cultures were processed using the Bactec blood culture system. Organisms were identified through routine bacteriological procedures. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using the automated Phoenix system (Becton-Dickinson, MD, USA). Results were interpreted according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines.

The anti-staphylococcal activity of ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam was disregarded, as it has been recommended to exclude testing and reporting of staphylococcal susceptibility to ceftazidime. Therefore, by testing, methicillin was not performed, and staphylococcal strains were considered resistant to these two agents (10, 11).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

A t-test was used to compare antimicrobial susceptibility values between two dependent proportions.

4. Results

A total of 73 bacteremia episodes were included in the survey. In this study, 15 patients with contaminated blood cultures and 6 patients with fungemia were excluded. The participants’ mean age was 61.2 ± 15.3 years, and 58% were females. No polymicrobial bacteremia was detected. The most frequent underlying diagnosis was diffuse large B cell lymphoma (n = 13, 25%), followed by acute myeloid leukemia (n = 11, 21%) and multiple myeloma (n = 4, 8%). The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 61.2 ± 15.3 |

| Gender (female) | 31 (58) |

| Underlying diagnosis | |

| Solid tumors | 16 (30) |

| Breast cancer | 5 (9) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2 (4) |

| Bladder cancer | 1 (2) |

| Cervix carcinoma | 1 (2) |

| Cholangiocellular carcinoma | 1 (2) |

| Colon carcinoma | 1 (2) |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 1 (2) |

| Ovarian cancer | 1 (2) |

| Rectal cancer | 1 (2) |

| Sarcoma | 1 (2) |

| Stomach cancer | 1 (2) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 37 (70) |

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | 13 (25) |

| AML | 11 (21) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 (8) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1 (2) |

| Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma | 1 (2) |

| Aplastic anemia | 1 (2) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 (2) |

| Plasma cell leukemia | 1 (2) |

| Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia | 1 (2) |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | 1 (2) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 (2) |

| Follicular lymphoma | 1 (2) |

| Total | 53 |

Abbreviation: AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

4.1. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

Antiviral, antibacterial, or antifungal prophylaxis was ongoing in 31 patients (58.5%). Antibacterial prophylaxis was used by 25 patients (47.1%), including 20 on co-trimoxazole, 18 on levofloxacin, and 1 on cefuroxime axetile. Antifungal prophylaxis was administered to 26 patients (49.0%), with 20 cases receiving fluconazole, 3 cases of posaconazole, 2 cases of voriconazole, and 1 case of liposomal amphotericin B. Antiviral prophylaxis was prescribed for 27 patients (51%), all of whom were taking valacyclovir.

Comorbid Conditions: Among the patients, 35 subjects (66%) had comorbidities, including 19 (36%) with hypertension, 13 (24.5%) with diabetes mellitus, 9 (17%) with ischemic heart disease, 7 (13.2%) with hyperlipidemia, 4 (7.5%) with pulmonary emboli, 4 (7.5%) with hypothyroidism, 4 (7.5%) with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, 2 (3.7%) with obstructive sleep apnea, 2 (3.7%) with anal fissure, 2 (3.7%) with chronic kidney disease, and 6 (11.3%) with other conditions.

4.2. Infection History

A history of previous infections within the last 3 months was recorded in 19 (35.8%) patients, including 9 (17%) with urinary tract infections (UTIs), 3 (5.6%) with bloodstream infections, 2 (3.7%) with infectious diarrhea, 2 (3.7%) with lower respiratory tract infections, 2 (3.7%) with skin and soft tissue infections, and 1 (1.8%) with an upper respiratory tract infection.

4.3. Microbiological Findings

Among the 73 isolates, 19 (26%) were gram-positive organisms; however, gram-negative organisms accounted for 54 (74%) of the bacteremia episodes. The most frequently isolated microorganisms included Escherichia coli in 22 (30%) cases, Klebsiella pneumoniae in 16 (22%) cases, and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) in 8 (11%) cases. Out of 11 Staphylococcus aureus isolates, 6 (8%) were methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Pseudomonas aeruginosa was found in 5 (7%) of the bloodstream infections.

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Rate of Monotherapy

Antibiotic susceptibilities of the bacteria isolated from blood cultures were analyzed to assess the effectiveness of empiric antimicrobial therapy. Among gram-negative microorganisms, the susceptibility rates of commonly used monotherapy antibiotics for febrile neutropenia were reported for ceftazidime 30 (56%), piperacillin/tazobactam 41 (76%), cefepime 29 (54%), and meropenem 43 (80%). Ceftazidime-avibactam had the highest susceptibility rate at 91%, followed by colistin at 87%, amikacin at 83%, and tigecycline at 81%. For gram-positive organisms, a 100% susceptibility rate was observed for vancomycin, tigecycline, and linezolid. The susceptibility patterns of gram-negative and gram-positive microorganisms are summarized in Tables 2. and 3.

| Variables | PIP-TAZO | CAZ | FEP | MEM | AK | CIP | TGC | CT | CAZ-AVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (n = 22) | 20 | 13 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 9 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| K. pneumoniae (n = 16) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 14 | 12 | 15 |

| P. aeruginosa (n = 5) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Acinetobacter spp. (n = 4) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Aeromonas spp. (n = 2) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| S. maltophilia (n = 1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| E. cloacae (n = 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vibrio spp. (n = 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| P. mirabilis (n = 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| R. mucosa (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total (n = 54) | 41 (76%) | 30 (56%) | 29 (54%) | 43 (80%) | 45 (83%) | 21 (46%) | 44 (81%) | 47 (87%) | 49 (91%) |

a PIP-TAZO, piperacillin-tazobactam; CAZ, ceftazidim; FEP, cefepim; MEM, meropenem; AK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TGC, tigecycline; CT, colistin; CAZ-AVI, ceftazidim-avibactam.

| Variables | PIP-TAZ | FEP | MEM | CIP | TGC | VA | LZD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoNS (n = 8) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (n = 6) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Enterococcus faecalis (n = 2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| α–hemolytic Streptococcus (n = 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Corynebacterium simulans (n = 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus (n = 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total (n = 19) | 12 (63%) | 10 (53%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (53%) | 19 (100%) | 19 (100%) | 19 (100%) |

a CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci; PIP-TAZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; FEP, cefepime; MEM, meropenem; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TGC, tigecycline; VA, vancomycin; LZD, linezolid.

4.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Rate of Combination Therapy

The antibiotic combinations were considered efficient with the understanding of the susceptibility of one of the antimicrobials in the combination regimen at the minimum. Tigecycline-based combinations had higher susceptibility rates, with more than 90%. The sensitivity rates of ceftazidime (P = 0.033), cefepime (P = 0.046), and ciprofloxacin (P = 0.018) monotherapies were significantly lower than their combinations with amikacin. The antimicrobial sensitivity rates for combination regimens are shown in Table 4.

| Variables (N = 73) | Susceptibility a | Susceptibility in Combination with | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinolones a | P-Value | Amikacin a | P-Value | Tigecycline a | P-Value | ||

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 53 (73) | 57 (78) | > 0.05 | 57 (78) | > 0.05 | 70 (96) | 0.05 |

| Meropenem | 55 (75) | 58 (79) | 0.05 | 57 (78) | > 0.05 | 71 (97) | 0.05 |

| Tigecycline | 62 (85) | 69 (95) | > 0.05 | 70 (90) | > 0.05 | NA | NA |

| Amikacin | 45 (62) | 55 (75) | > 0.05 | NA | NA | 70 (96) | 0.009 |

| Ceftazidime | 31 (42) | 44 (60) | > 0.05 | 47 (64) | 0.033 | 68 (93) | 0.0011 |

| Cefepime | 38 (52) | 46 (63) | 0.05 | 54 (74) | 0.046 | 69 (95) | 0.0011 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 35 (48) | NA | NA | 55 (75) | 0.018 | 69 (95) | 0.0005 |

| Colistin | 47 (64) | 59 (80) | > 0.05 | 50 (68) | > 0.05 | 70 (96) | 0.015 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | 50 (68) | 57 (78) | > 0.05 | 53 (73) | > 0.05 | 64 (88) | > 0.05 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.6. Resistance Profile

Klebsiella pneumoniae had the highest proportion of resistant strains, with 7 (44%) extensively drug-resistant (XDR), 4 (25%) extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), and 2 (12.5%) multidrug-resistant (MDR). Among E. coli strains, 5 (22.7%) of them produced ESBL, 3 (13.6%) of them had MDR, and no XDR was detected. Methicillin-resistance rate was 70% in staphylococcal strains. Resistance patterns are shown in Table 5.

Abbreviations: XDRO, extensively drug-resistant organisms; MDRO, multi-drug resistant organisms; ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci.

a All MDRO are methicillin-resistant.

5. Discussion

The most commonly isolated pathogens were E. coli, followed by K. pneumoniae among gram-negative microorganisms, and CoNS among gram-positive microorganisms. Similar findings have been reported in the literature (3, 12, 13). Although there were no significant changes in the bacterial spectrum, the increasing antimicrobial resistance patterns will pose challenges for treating clinicians and might necessitate modifications of empirical therapeutic approaches to prevent poor outcomes. Consequently, antimicrobial resistance could undermine the effectiveness of the antimicrobial therapy recommendations provided by the most recent guidelines. This study demonstrated that the monotherapy regimens endorsed by the current guidelines (3, 14) covered less than one-fourth of FN patients with bacteremia. Therefore, new recommendations that consider the severity of FN patients, in particular, should be provided.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) is a recent worldwide concern. The prevalence of colonization by carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae has progressively increased in recent years (15). Accordingly, carbapenem resistance among gram-negative microorganisms isolated from blood cultures was observed to be associated with high mortality in FN patients (16). In the present study, almost half of K. pneumoniae and all Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains were resistant to carbapenems. Therefore, these excessively high rates necessitate consideration of carbapenem resistance in empirical FN treatment in such settings. The question arises of how carbapenems alone can be used to treat severe FN patients empirically, especially in the presence of such resistance.

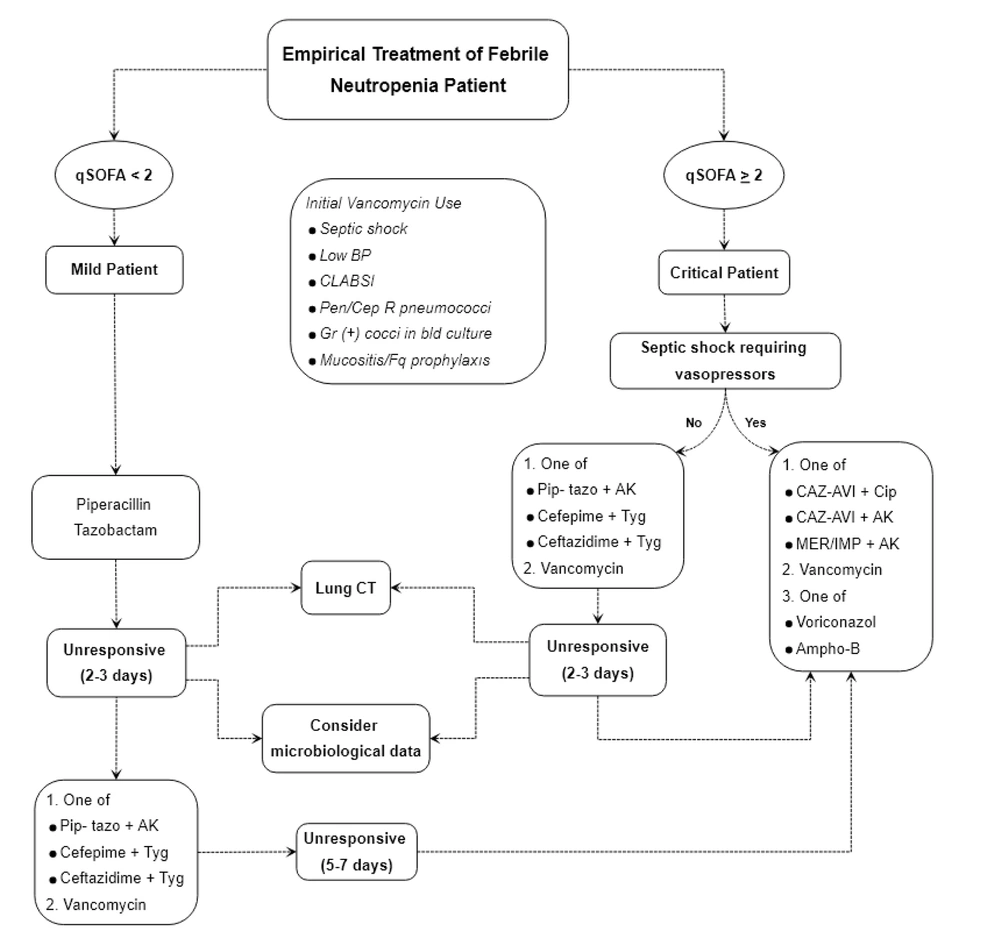

Although current guidelines recommend standard monotherapy for all FN patients, the severity of FN patients should be considered when determining the empirical regimen in highly resistant settings. Various criteria have been suggested for identifying the risk factors of CRE-bloodstream infection (BSI) in immunocompetent patients, including severe sepsis or septic shock at presentation (17). It has also been shown that the qSOFA score can be a useful bedside tool in predicting the prognosis of FN patients (8, 18). Therefore, this study suggests using the qSOFA score, along with the vasopressor requirement, as a quick evaluation tool for classification (Figure 1).

Febrile neutropenia management algorithm by using quick sequential organ failure assessment (qSOFA) score along with vasopressor requirement. AK: Amikacin; Ampho-B: Liposomal amphotericin B; BP: Blood pressure; CAZ-AVI: Ceftazidim avibactam; Cep: Cephalosporin; Cip: Ciprofloxacin; CLABSI: Central line associated blood stream infection; Fq: Fluoroquinolone; IMP: Imipenem; MER: Meropenem; Pen: Penicillin; Pip-tazo: Piperacillin tazobactam; R: Resistant; Tyg: Tigecycline.

An effective antimicrobial stewardship program has been shown to reduce mortality in FN patients, even when broad-spectrum antimicrobial regimens are necessary due to the potential for colonization with resistant pathogens (19). In highly resistant settings, part of antimicrobial stewardship involves sparing carbapenems in appropriate patients (20). Given the widespread carbapenem resistance in the studied facility, it seems reasonable to avoid carbapenems in relatively mild infections and consider other monotherapy options. On the other hand, in Bahrain, the available antipseudomonal cephalosporins, ceftazidime, and cefepime have lower efficacy compared to piperacillin-tazobactam. Therefore, piperacillin-tazobactam appears to be a reliable agent for the treatment of mild FN patients.

However, intravenous (IV) combination therapy could be considered when antimicrobial resistance is suspected, especially considering the high resistance profiles of infecting microorganisms in Bahrain. Antibiotic combinations are inevitable in the management of critically ill patients, in particular. According to the present study data, there were significant differences between ceftazidime/cefepime monotherapies and their combinations with tigecycline. Therefore, it would be an appropriate approach to use these antibiotics in combination with tigecycline in critically ill patients who do not require vasopressors. Although the use of tigecycline in bacteremia is controversial, as it is known to be bacteriostatic and has low serum levels (21), it has been reported that combination therapy with tigecycline is more effective than monotherapy in FN patients with BSI (22). The present study revealed that tigecycline-based combinations provide broad coverage and can be used in critical patients.

The empirical use of vancomycin is currently recommended only in certain criteria, including cases of shock, according to current guidelines (3, 23). However, critical FN patients with sepsis (qSOFA ≥ 2) are not included in these guidelines when hypotension is absent. Given the 10% rate of methicillin resistance among gram-positive bacteria in the present study and the high mortality rates associated with the inappropriate use of antibiotics in FN patients, it is recommended to use vancomycin empirically in all patients with critical status.

Sepsis is a highly critical condition that requires immediate administration of appropriate antibiotics (24). The use of carbapenems might be inadequate due to the high incidence of CRE in the studied hospital. In CRE patients, empirically recommended antibiotics include ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam due to their efficacy against carbapenemase-producing microorganisms (25). This study has included ceftazidime-avibactam in the flowchart since it is available in the studied facility and has more than 90% efficacy against gram-negative pathogens. However, using ceftazidime-avibactam in combination therapy is more appropriate since it is ineffective against gram-positive bacteria and Acinetobacter spp. (10).

This study is limited by its retrospective design. Nevertheless, the study's strength lies in its inclusion of only blood cultures to assess microbiological data, limiting the inclusion of colonizers. In conclusion, the in vitro findings of the present study suggest that clinical severity and local epidemiological data should be considered in FN management rather than applying a uniform approach to all patients. Antibiotics targeting CRE can be considered part of combination therapy in selected cases in settings with high XDR rates. Tigecycline can be considered due to its broad coverage, but only in combination therapy. Given the rate of gram-positive infection in FN patients, vancomycin should be considered in cases of sepsis (qSOFA ≥ 2), in addition to glycopeptide indications in the current guidelines. However, further clinical studies are needed to confirm the clinical relevance of these in vitro findings. Finally, the increasing rates of resistance emphasize the need for effective antimicrobial stewardship programs.