1. Context

Blastocystis spp. is a unicellular, obligate anaerobic protozoan, which is observed in the human intestinal tract, and colonizes many vertebrates and invertebrates (1), which are considered as a reservoir host for humans (2). Over the past 100 years, Blastocystis spp. has had a varied taxonomic history, being described as a non-pathogenic yeast. In the 1970s to 1980s its biological and clinical properties were considered for the first time (3, 4). Despite a century has passed since its detection, only four morphological forms (cyst, granular, Vacuolar and amoeboid) and two transient stages (multi vacuolar and vacuolar) were detected, and there are many unknowns about it (5-7). Although many researchers have given credit to Blastocystis spp. as a pathogen (3, 8) and attributed symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, vomiting, headaches, skin rash, joint pain and psychiatric illness to it (9-11), yet there is still much debate about the pathogenicity of this protozoa in humans. Many studies have verified water resistant thin-walled cysts (responsible for autoinfection) and water resistant thick-walled cysts in feces and contaminated water and food (12); this explains the importance of the oral-fecal route as the main form of transmission of Blastocystis spp. in human-human or animal- human transmission. Zoonotic transmission was reported in animals such as chicken, horse and pig (6, 12, 13). Blastocystis was recommended as one of the indicators of fecal contamination of source water by the World Health Organization (14). Based on morphological criteria, Blastocystis spp. isolates from animals and humans are almost indiscernible (3).

Based on differences in some properties such as host source, morphology, in vitro culture characteristics and/or phylogenetic analysis of SSU rRNA gene sequences of Blastocystis isolates, 17 subtypes (STs) from different mammalian, avian and amphibian species have been described, with subtype 1 - 9 being found in humans (15-17). Seven standardized ST-specific STS primers (ST1-7) have been used in epidemiological studies and other studies on relevant factors such as hosts, transmission and zoonoses (15, 17). Only four of them are prevalent (ST1, ST2, ST3 and ST4) and show around 90% of the subtyped isolates. The majority of infections with Blastocystis spp. in humans are attributable to ST3, but infections with ST1, ST2 and ST4 are also frequent (18-20). ST5 to ST9 have been isolated only rarely from humans (2, 21, 22) while ST10 - ST17 have not been found in humans (23-25). Blastocystis hominis is a suggested name for the organism isolated from human fecal by Brumpt (26). Various studies have demonstrated that humans with close animal contact (food and animal handlers) have a higher risk of infection with Blastocystis spp. (2, 3, 27, 28).

Although B. hominis was obtained from many studies on fecal samples (29), no review study has been done on prevalence and genotype analysis in Iran. Against this background, we performed a systematic review of the literature to identify the situation of this parasite in Iran. This study could help policy makers with an evidence-based summary of the primary literature on decisions.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Search Strategy

PubMed, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, Ovid, Google scholar, and national databases including SID, Iranmedex and Magiran were searched for studies in English and Persian language to identify prevalence B. hominis in Iran, until July 2015. The following search terms were used: “Blastocystis hominis” OR “Blastocystis” AND “prevalence” OR “epidemiology” AND “Iran”. English and Persian language articles were recognized by two independent researchers and the appropriate studies were carefully chosen for evaluation.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Trial Selection

We included population-based studies that reported the prevalence of B. hominis among the Iranian population, including case reports, case-series, and letter to editor while non-Iranian studies were excluded.

2.3. Quality Assessment

The quality of the retrieved studies was assessed using the STROBE (30).

2.4. Data Extraction

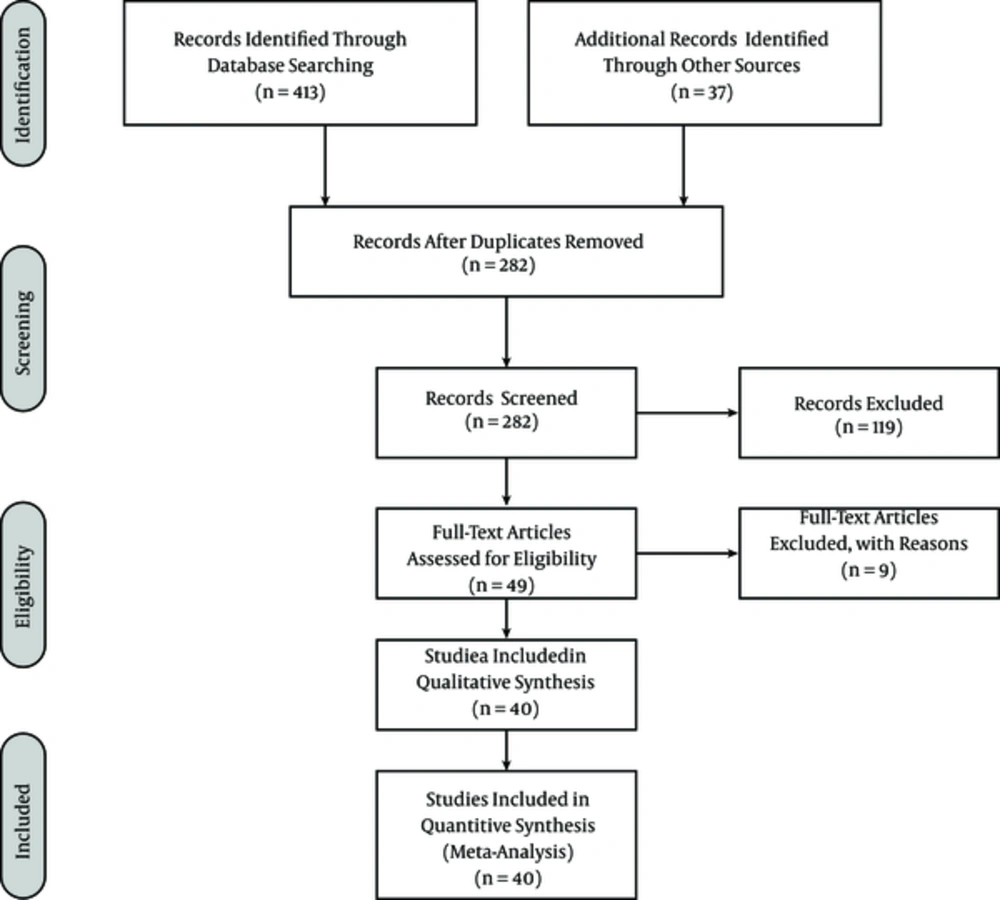

Two of the authors independently extracted data from the selected papers and disagreements were resolved by discussions between the authors. The extracted information from the studies included the first author, year of publication, sample size, the study population, prevalence of intestinal parasites, prevalence of studies, and study region. Four hundred and thirteen potentially related studies were identified from the initial searches, but only 40 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The article selection procedure is shown in Figure 1.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

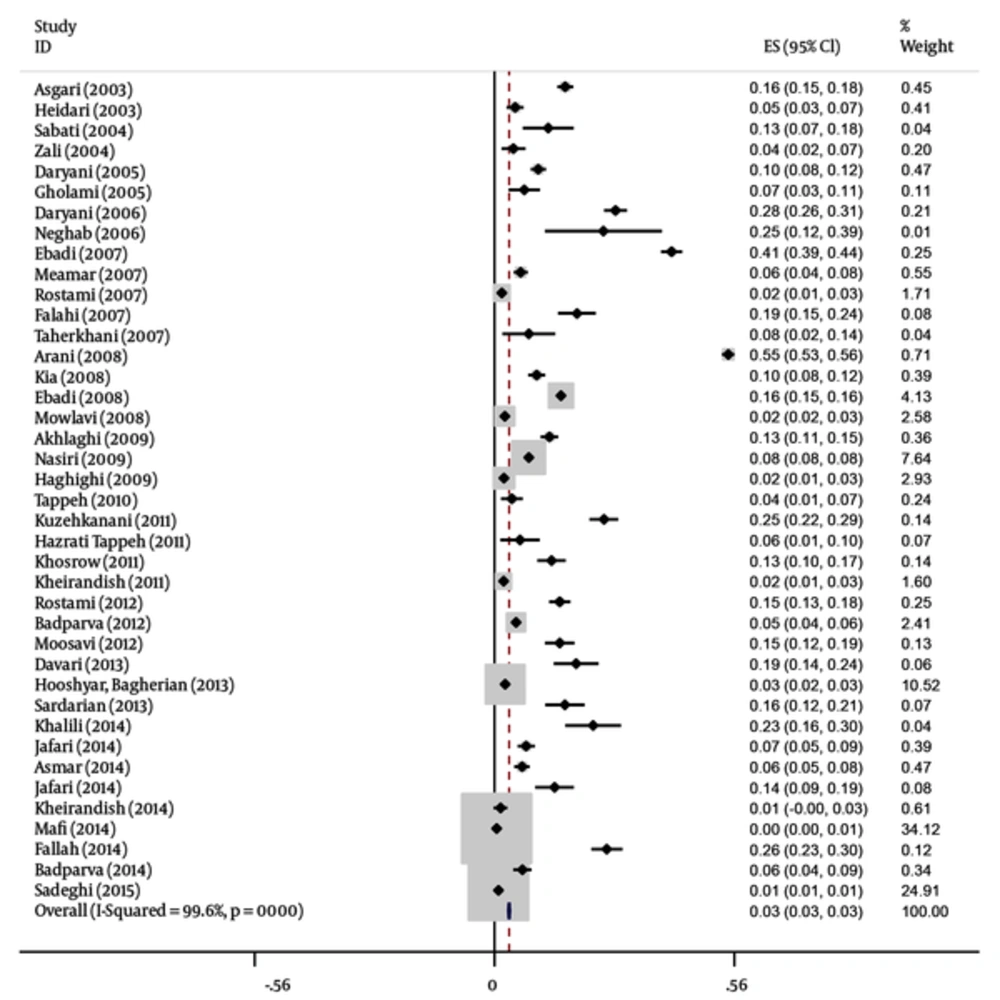

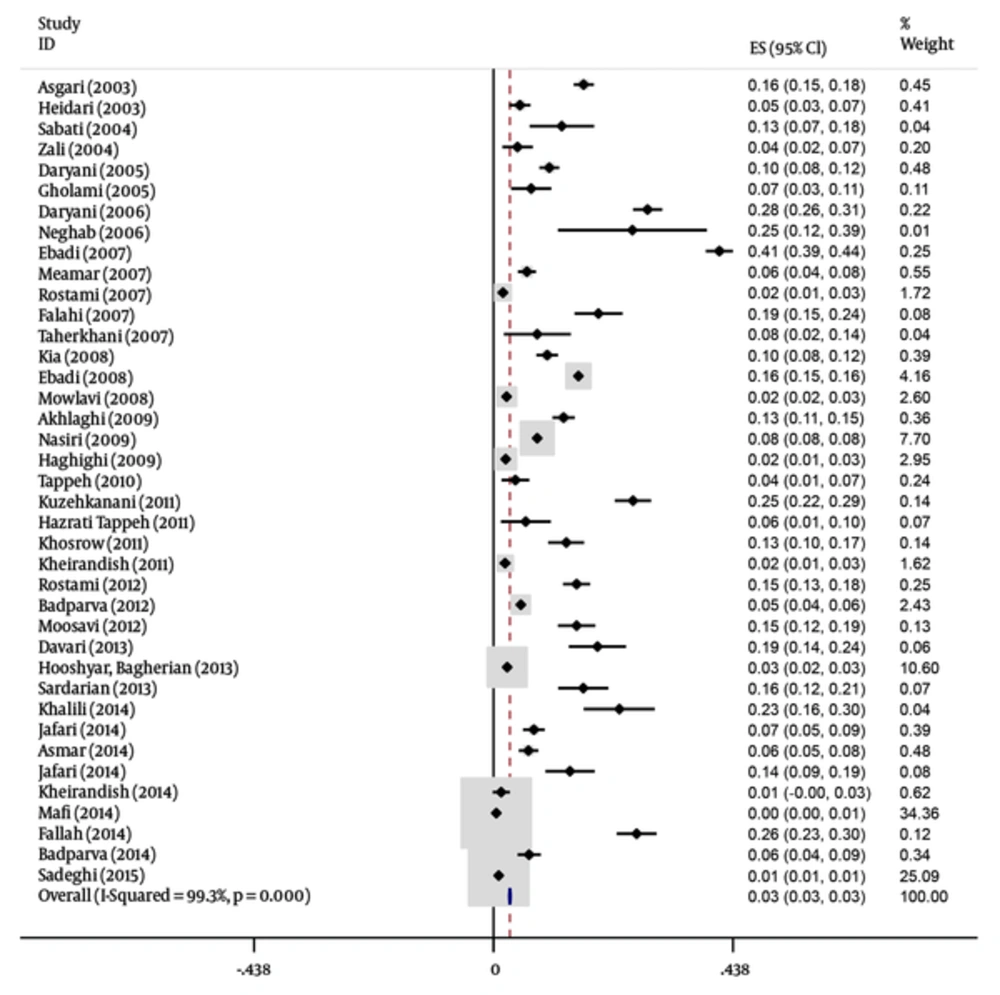

We estimated prevalence using the meta-analysis random effect methods model (using the DerSimonian and Laird method) with confidence interval heterogeneity between studies assessed by using I square and Cochran’s Q tests. Publication bias was examined by egger test and funnel plot. P < 0.05 was considered significant. To ensure the robustness of the results, a sensitivity analysis was performed. This was done to demonstrate the impact of any study done on the final result. To this end, a study came out and then a sensitivity analysis was performed in its absence. The analyses were conducted with STATA software, version 12 (Produced by StataCorp, USA) (9, 31-69).

3. Results

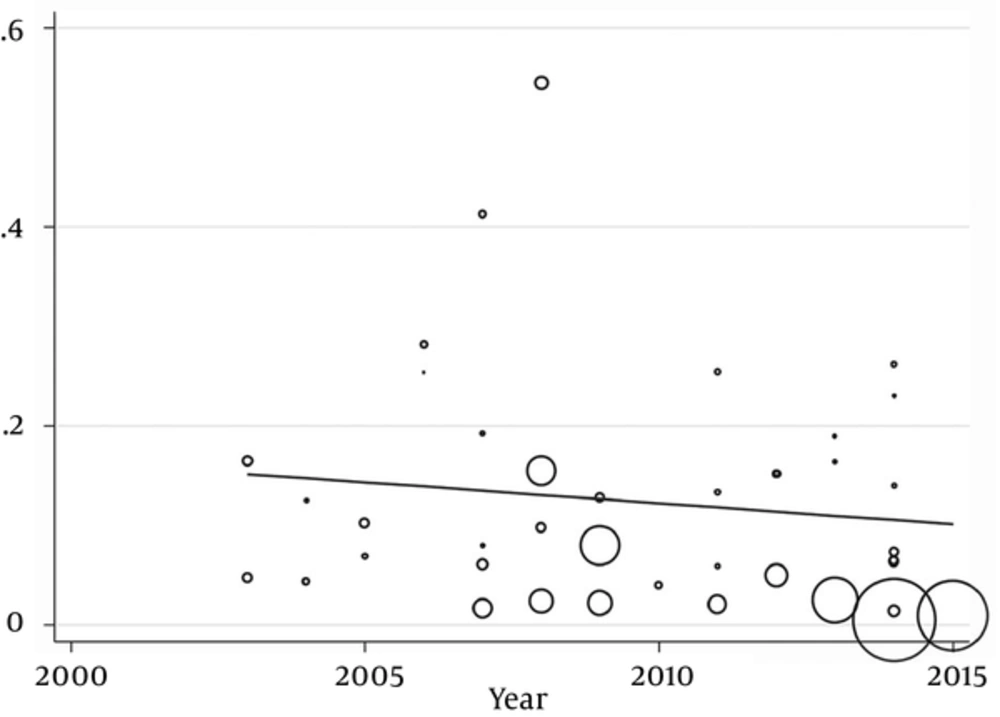

In this meta-analysis, 40 studies published between 2003 and 2015 were identified and entered into the final analysis, to measure the prevalence of B. hominisis among symptomatic patients and asymptomatic individuals. Quality assessment showed that 25 articles (62.5%) had good quality, eight articles (20%) had medium quality and seven articles (18.5%) had poor quality. It seemed that in the reported results, publication bias occurred (P = 0.001). The total prevalence of B. hominisis was 3% (95% CI, 3 - 3). The results showed that this relationship was not statistically significant; however, B. hominisis prevalence rate decreased during this period. The results showed that prevalence of blastocystosis had a decreasing trend in Iran. The performed studies are presented in Tables 1 and 2 along with three illustrations.

| Reference | Region | Number of Stool Samples | The Study Population | Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites | Prevalence of Blastocystis | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Arani et al. 2008) | Tehran | 4371 | Patients | 10.7 | 54.5 | First |

| (Ebadi et al. 2007) | Yazd | 1500 | Children ≤ 14 years | 8.5 | 41.3 | First |

| (Daryani et al. 2006) | Northwest of Iran | 1070 | School children | 52 | 28.2 | First |

| (Kuzehkanani et al. 2011) | Bandar Abbas | 656 | Rural inhabitants | 48.8 | 25.5 | First |

| (Neghab et al. 2006) | Shiraz | 39 | Food handlers | 59.4 | 25.4 | First |

| (Khalili et al. 2014) | ShahreKord | 160 | Hospitalized children | 36.25 | 23 | First |

| (Davari et al. 2013) | Ardabil | 216 | Mental disabilities | 44 | 19 | First |

| (Rostami et al. 2012) | Gorgan | 800 | School children | 28.8 | 15.2 | First |

| (Akhlaghi et al. 2009) | Tehran | 1000 | Patients | 21.2 | 12.8 | First |

| (Sabati et al. 2004) | Abu Musa | 120 | School children | 27.5 | 12.5 | First |

| (Jafari et al. 2014) | Isfahan | 652 | Patients | 10.42 | 7.36 | First |

| (Asmar et al. 2014) | Bandar Anzali | 700 | Inhabitants | 15.1 | 6.4 | First |

| (Meamar et al. 2007) | Tehran | 781 | HIV+/AIDS patients | 11.4 | 6.1 | First |

| (Rostami et al. 2007) | Iran | 706 | Renal transplant recipients | 4.5 | 1.7 | First |

| (Falahi et al. 2007) | Khorramabad | 306 | HIV+/AIDS patients | 22.5 | 19.2 | Second |

| (Asgari et al. 2003) | Eslamshahr | 1535 | Inhabitants | 53.2 | 16.5 | Second |

| (Jafari et al. 2014) | Hamedan | 228 | Inhabitants | 35.1 | 14 | Second |

| (Daryani et al.2005) | Ardabil | 1070 | Primary school students | 27.7 | 10.2 | Second |

| (Kia et al. 2008) | Mazandaran | 855 | Rural inhabitants | 25 | 9.8 | Second |

| (Taherkhani et al. 2007) | Kernanshah | 75 | HIV+/AIDS patients | 36 | 8 | Second |

| (Hazrati Tappeh et al. 2011) | Urmia | 101 | patients | 19.8 | 5.9 | Second |

| (Badparva et al. 2012) | Lorestan | 2838 | Inhabitants | 16.5 | 5 | Second |

| (Zali et al. 2004) | Iran | 206 | HIV+/AIDS patients | 18.4 | 4.4 | Second |

| (Hooshyar, Bagherian et al.) | Kashan | 6348 | Patients | 7.6 | 2.5 | Second |

| (Ebadi et al. 2008) | Yazd | 13388 | Patients | 8.6 | 15.51 | Third |

| (Khosrow et al. 2011) | Western Azerbaijan | 405 | Primary school students | 42.5 | 13.3 | Third |

| (Nasiri et al. 2009) | Karaj | 13915 | Inhabitants | 4.7 | 8 | Third |

| (Gholami et al. 2005) | Babol | 181 | Cattle breeders | 31.5 | 6.9 | Third |

| (Mowlavi et al. 2008) | Khuzestan | 1494 | Nomads | 25.36 | 2.4 | Third |

| (Haghighi et al. 2009) | Zahedan | 1562 | Patients | 27.3 | 2.2 | Third |

| (Kheirandish et al. 2011) | Khorramabad | 816 | Bakery workers | 11.9 | 2.1 | Third |

| (Kheirandish et al. 2014) | Khorramabad | 210 | Food handlers | 9 | 1.4 | Third |

| (Sadeghi et al. 2015) | Qazvin | 5739 | Patients | 5.92 | 0.94 | Third |

| (Mafi et al. 2014) | Iran | 4200 | Patients | 2.4 | 0.5 | Third |

| (Tappeh et al. 2010) | Urmia | 225 | Mentally disabled | 20.4 | 4 | Fourth |

| (Heidari et al. 2003) | Damghan | 461 | Children ≤ 6 years | 68.1 | 4.8 | Seventh |

| (Fallah et al. 2014) | Tabriz | 558 | 2-20 years | - | 26.17 | - |

| (Sardarian et al. 2013) | Hamedan | 250 | Patients | - | 16.4 | - |

| (Moosavi et al. 2012) | Tehran | 420 | Patients | - | 15.2 | - |

| (Badparva et al. 2014) | Khorramabad | 511 | Patients | - | 6.5 | - |

| Total | Iran | 61000 | - | 24.94 | 12.52 | - |

| Provience [Reference] | Number of Stool Samples | Subtype 1 | Subtype 2 | Subtype 3 | Subtype 4 | Subtype 5 | Subtype 6 | Subtype 7 | Unknown Subtype/ Mixed Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tehran (Moosavi, 2012) | 174 | 48(27.5%) | 7 (4%) | 53 (30.5%) | - | 33 (19%) | - | - | 33 (19%) |

| (Lorestan( (Badparva,2014) | 30 | - | 4 (13.3%) | 17 (56%) | - | 6 (20%) | - | - | 3 (10%) |

| Hamadan (Sardarian, 2013) | 41 | 23 (56.1%) | 3 (7.3%) | 9 (23%) | - | - | - | - | 6 (14.4%) |

| Total | 285 (100%) | 91 (31.9%) | 14 (4.9%) | 95 (33.3%) | - | 43 (15.1%) | - | - | 42 (14.8%) |

Blastocystis hominisis is presumably the most common protozoan found in human faecal samples of both symptomatic patients and asymptomatic individuals worldwide. Blastocystis infection rate has a prevalence ranging from 1.5% to 20% in industrialized countries, whereas in developing countries the rate is 30% to 50% (70). Blastocystis spp. is now recognized as an emerging zoonosis by many researchers (12). Regarding the pathogenic potential of Blastocystis, it was widely debated in the literature during the last two decades because the organism can be found in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Our study demonstrated that the prevalence of Blastocystis spp. rate in Iran was 3% between 2003 and 2015. The prevalence of B. hominis in the USA has decreased significantly over the last two decades from 2.6 to 23%, which may be epidemiologically significant; and increasing prevalence rates were also noted in the recent years. This prevalence rate was in line with other studies from Switzerland (16.7% - 19.0%) (71) and Taiwan (20.4) (72), yet the rate reported from Chile (61.8%) (73) and Albanian (54.5%) (74) was considerably higher than our results.

In epidemiological studies, genomic researches are more advantageous than other methods; because, firstly they are more sensitive and able to detect all the morphological forms, live and dead microorganisms (22), secondly, these studies are the only way to identify the subtypes of microorganisms (2, 15, 27) and thirdly, they can act as a complement to previous studies. Moreover, diagnoses of subtypes that in special conditions tend to specific host only perform in genomic studies (2, 15, 17, 27, 28). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review study on epidemiology of Blastocystis spp. in Iran. In this study, we reviewed all studies focusing on the prevalence and significance of intestinal parasite infections among different age groups, geographical, continental and cultural conditions in Iran in the last decade. In addition, we also investigated a few studies about the genomic properties of Blastocystis that were done in this region. The results showed that the average prevalence rate of B. hominis by common diagnostic methods (wet mount, concentration assays and in some cases staining methods) is 12.25%. Previous studies demonstrated that this rate in industrialized countries is 1.5 to 20% (70, 75), while it is 30% - 50% in developing countries (75). In 38.9% of studies, which investigated parasitic infection, B. hominis was the most common intestinal parasite and in 94.3%, it was the first to third most common parasite. Accordingly, the prevalence rate of B. hominis is higher than other intestinal parasites in Iran. In the USA, the prevalence of this protozoan increased from 2.6 to 23% in the recent 20 years. In some states it is known as an emerging parasite and a hygiene warning (12, 76, 77). The interesting point is that, despite hygiene promotion, the prevalence of parasites, which have been transmitted in similar ways, has decreased (32). This may be due to unknown transmission pathways and it needs more studies to clarify the matter. There has been less attention to B. hominis in the diagnostic and training field in Iran and clinicians do not believe in pathogenicity and its treatment that may play a role in increasing its prevalence.

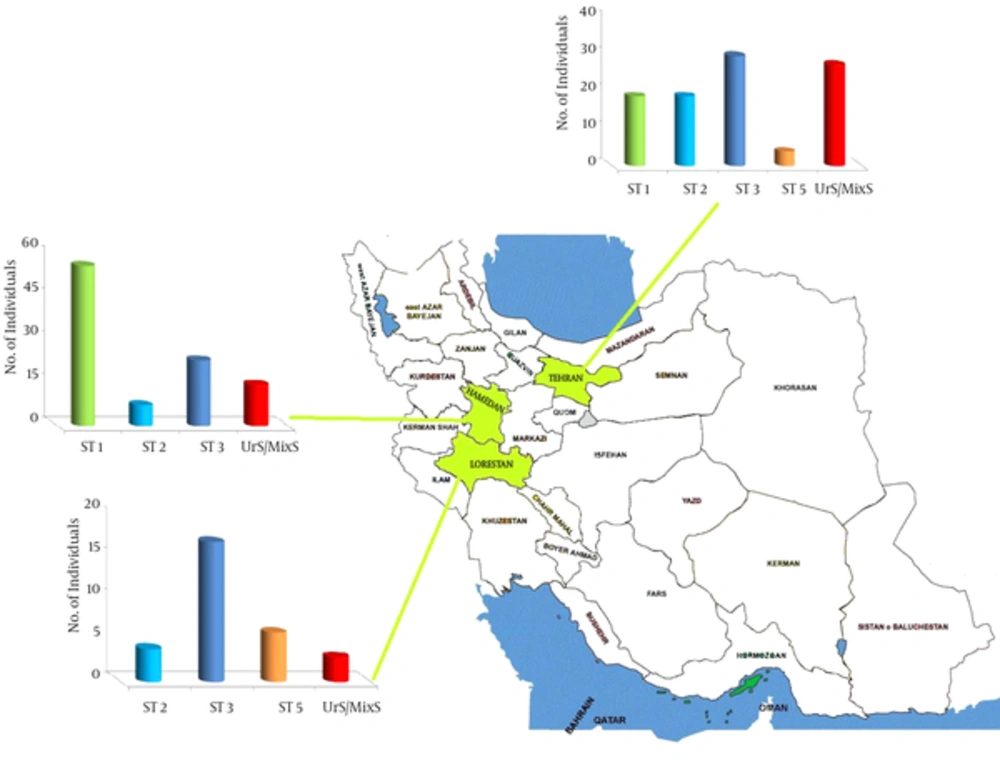

Result of only three genomic studies that were performed in Iran (36, 60, 64) are similar to many studies performed in other regions of the world that have reported ST3 as the most common subtype of B. hominis in the world (7% - 92%) (78, 79). Some researchers have attributed ST3 to urticaria, HIV and cancer (80). However, 13.3% of bovine Blastocystis subtypes are ST3 in Iran (81) that may influence the dissemination and transmission between the two hosts. Although, the second and third subtypes were ST1 and ST5, they have not been reported in all studies in Iran. Furthermore, ST1 is known as a pathogenic subtype in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms (20, 78, 79). Mostly, ST5 has been found in cattle and pigs (2) and it has been reported in some regions such as Sweden (82). Since 98% of the Iranian population are Muslims and pork is rarely consumed because it goes against Islamic law, and on the other hand, 60% of bovine subtypes is ST3 in Iran (81), it is inferred that cattle can be the host of ST5 in the region.

To ensure strong results, we removed one of the studies to analyze the sensitivity. When the Asghari et al. study (31) was excluded the overall prevalence did not change.

4. Conclusions

Another subtype, which was found in this study, was ST2 that is considered as the second most common subtype around the world (27), but the relationship between human and monkeys is infrequent in Iran. Since geographical distribution of ST2 is similar to ST3 in Iran, it is likely that their ways of transmission is very similar. Some conflicting reports have been published on the pathogenesis of ST2. There are several studies verifying its high degree of infectivity (19), whereas some others have not confirmed the infectivity of ST2 (17). Although, ST6 and ST7 are known as the bird subtypes (83), in a study on birds, ST2 was also reported as a bird subtype (84). Future studies should reveal whether this is an exception or the rule. It should be pointed out that in the study conducted on birds of Khorramabad, Blastocystis spp. was not observed (85).

Although Blastocystis genomic studies on humans and animals are common in many regions of the world, these studies are rare in Iran and belong to the recent years and limited to some specific areas in the country (36, 60, 64). We hope that similar investigations will be expanded in the future to collect more useful information to help health policy makers in this region to better understand the prevalence and pattern of the disease.