1. Background

Dysentery refers to an inflammatory bowel disease caused by microorganisms invading the intestinal mucosa (1). Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) and Shigella flexneri are two major etiologic agents in the development of this disease in humans, particularly in infants. These bacteria invade the human colon epithelium, causing acute mucosal inflammation, severe tissue damage, abscesses, and ulceration, which result in watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, cramping, and bleeding (2, 3). The main virulence factors involved in the attachment, invasion, and intracellular proliferation of these bacteria are carried on a large pathogenic plasmid called pInv. The pInv plasmid is composed of genes encoding a type 3 secretion system (T3SS), effector proteins, and transcriptional regulators. Transcriptional regulators such as virF and virB, which play critical roles in the activation of virulence factors, are also encoded by pInv (4-6). The virF protein is a 30-kDa protein of the AraC family that is conserved in both EIEC and Shigella. It also plays a role in the activation of certain chromosomal genes, acting as a global gene expression regulator. VirF activates the virB gene, which encodes a secondary transcriptional activator, virB, leading to the activation of promoters of pInv virulence genes. The activation of these virulence genes enables bacterial invasion into the colon epithelium and progression of the disease to dysentery. Therefore, any factor that influences the expression of the virF gene can impact the bacteria's virulence (7, 8). Scientific data show that virF gene expression changes in response to environmental signals such as temperature, pH, and osmolarity (9). In some bacteria, similar responses to other environmental stresses, such as antimicrobial pressure, have also been observed (10, 11). Several studies have reported that antibiotics at low concentrations can affect bacterial cell behaviors; in other words, the antimicrobial activity of antibiotics is not an "all-or-none" effect (12). Concentrations below the sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (sub-MIC) are suggested to influence bacterial virulence (13, 14). The sub-MIC effects of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin on the virulence of various bacteria have been documented in several studies. For instance, ciprofloxacin has been reported to affect the release of Shiga toxin (Stx) in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) (15) and reduce epithelial cell adhesion in uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) (16). Similarly, the sub-MIC effects of azithromycin on bacterial virulence, such as decreased biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and increased growth rate in pathogenic E. coli, have also been reported (17, 18).

According to the evidence, sub-MICs of antibiotics can reduce or increase bacterial virulence by altering gene expression, particularly the expression of genes encoding transcriptional regulators (16, 17, 19, 20). This phenomenon can influence treatment strategies and the prescribed doses of antibiotics for controlling bacterial infections. However, comprehensive data on whether sub-MICs of antibiotics affect the severity of Shigella and EIEC virulence are lacking. Consequently, the potential outcomes of using inappropriate antibiotic doses to treat infections caused by these bacteria remain unknown.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the administration of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe cases of shigellosis and diarrhea associated with E. coli pathotypes (21).

The sub-MIC effects of these two antibiotics on the virulence of different bacteria have been demonstrated in several studies. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect a similar effect on Shigella and EIEC. Considering that environmental factors influence the expression of virulence genes and, consequently, the invasive capability of these bacteria by altering the expression of the virF gene, the effect of sub-MICs of target antibiotics on the expression of this regulator gene may signify its role in the severity of infections caused by these bacteria.

2. Objectives

Thus, the present study aims to investigate the effect of sub-MICs of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin on the expression of virF in EIEC and S. Flexneri.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The experiments were performed on E. coli ATCC 43893 (prototype of EIEC) and S. flexneri ATCC 12022 strains. The strains were inoculated in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), and bacterial cultures were incubated at 37°C.

3.2. Determination of Sub-minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antibiotics Using the Microdilution Method

To determine the sub-MIC of antibiotics, the MIC for both bacteria was first established using the microdilution method. Three concentrations—1/2, 1/4, and 1/8 dilutions of MICs—were used as sub-MICs in the study. Stock concentrations of azithromycin (64 µg/mL) and ciprofloxacin (16 µg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) were prepared for the microdilution method. Seventy-five microliters of Muller-Hinton broth (MHB) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and 100 µL of serially diluted antibiotics were added to wells of a 96-well flat plate. A 0.5 McFarland suspension was prepared for EIEC and S. flexneri strains, diluted 1:300 in MHB, and 25 µL of this bacterial suspension was added to all wells. Negative controls contained only the culture medium, and positive controls contained bacterial culture without antibiotics.

The plate was placed in a plastic bag to prevent drying and incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. Optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 600 nm was measured using a Nanodrop system (Boeco, Germany), and the MICs for each antibiotic were determined.

3.3. RNA Extraction

RNA was extracted from fresh 18-hour cultures of bacteria treated with sub-MICs of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin, as well as from untreated bacterial cultures. Treated and untreated bacterial cultures were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellets were diluted with normal saline to 1 McFarland. RNA was extracted using RNA purification kits (Takara, Japan) following the manufacturer's protocol.

RNA concentrations and purity were evaluated by OD measurement at 260/280 nm using a Nanodrop. All RNA samples were diluted to 50 ng/µL with DNase/RNase-free distilled water. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on the housekeeping rpoA gene to confirm the absence of DNA contamination in RNA samples.

3.4. cDNA Synthesis

cDNA was synthesized from RNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Takara, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantity and quality of cDNA were measured using Nanodrop at an OD of 260 nm. All cDNA samples were adjusted to 500 ng/µL with distilled water.

3.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction

Polymerase chain reaction was conducted to assess the specificity of primers and optimize the amplification thermal conditions for the virF and rpoA genes. Amplifications were performed in reactions containing: Eleven µL of ready-to-use master mix 2X (Takara, Japan); 1 µL of 10 pmol forward and reverse primers; 10 µL of deionized distilled water; 2 µL of cDNA (1 µg/µL). Electrophoresis was performed on a 1.5% agarose gel to evaluate the PCR amplicons. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are detailed in Table 1.

| Target Gene and Primer Sequences (3′ → 5′) | Amplicon Size (bp) | Amplification Temperatures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| virF | 300 | 95ºC (30 s), 56ºC (30 s), 72ºC (30 s) | |

| F: TGACGGTTAGCTCAGGCAAT | |||

| R: TTTTGCCGAAAGGCATCTCT | |||

| rpoA | 325 | 95ºC (30 s), 59ºC (30 s), 72ºC (30 s) | |

| F: CGGTGAGAGTTCAGGGCAAA | |||

| R: TCGGTACGCTGTTCTACACG |

3.6. Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

The expression of the virF gene was evaluated using the relative real-time PCR method. Expression levels were compared among samples from fresh antibiotic-free cultures of EIEC and S. flexneri and cultures treated with sub-MICs of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin. Amplifications were performed in duplicate reactions.

Each reaction had a final volume of 20 µL, consisting of: Ten µL master mix SYBER Green 2X (Fermentase, Germany); 1 µL of each forward and reverse primers (10 pmol concentration); 6 µL of sterile distilled water; 2 µL of cDNA (1 µg/µL). Reactions were run over 40 cycles using a RotorGene Q PCR cycler (Qiagen, Germany) at the optimal temperatures specified earlier. The expression ratio of the virF gene was normalized using the rpoA internal control. Gene expression changes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. To confirm the absence of nonspecific amplicons and primer dimers, a melting curve analysis was conducted. Reactions were performed in four control setups: (1) Template + primer, (2) H2O + primer, (3) template + H2O, (4) H2O only.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Pairwise comparisons were used to analyze virF gene expression for each specific bacterial species using the Mann-Whitney U test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses and data visualization were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.

4. Results

4.1. Microdilution

The MIC values of azithromycin were determined to be 0.600 μg/mL for S. Flexneri and 1.200 μg/mL for EIEC. For ciprofloxacin, the MIC values were 0.032 μg/mL for S. Flexneri and 0.120 μg/mL for EIEC. The sub-MIC values calculated from these MICs are presented in Table 2.

| Strains | Antibiotic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (Sub-MIC) | Ciprofloxacin (Sub-MIC) | |||||

| 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | |

| Shigella flexneri(μg/mL) | 0.300 | 0.150 | 0.075 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.004 |

| EIEC (μg/mL) | 0.600 | 0.300 | 0.150 | 0.060 | 0.030 | 0.015 |

Abbreviations: EIEC, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli; Sub-MIC, Sub-minimum inhibitory concentration.

4.2. RNA, cDNA Quality Control, and Melting Curves

The purity of all RNA samples was confirmed by negative PCR results for the rpoA gene, indicating the absence of DNA contamination. All samples tested positive for both the rpoA and virF genes, demonstrating the reliability of the cDNA samples and primers. The absence of nonspecific amplicons and primer dimers was further confirmed by the presence of a single peak in the melting curves.

4.3. Gene Expressions

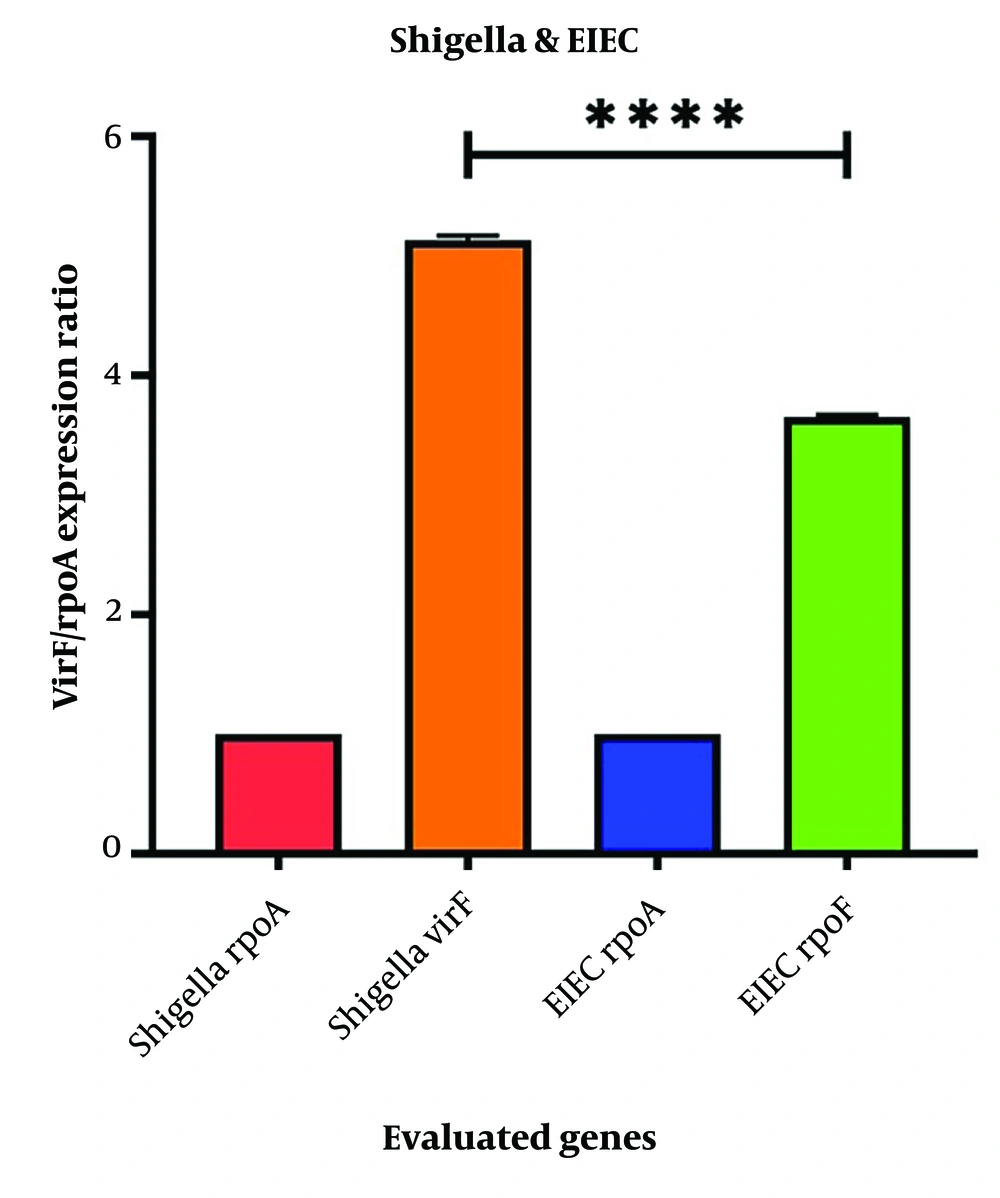

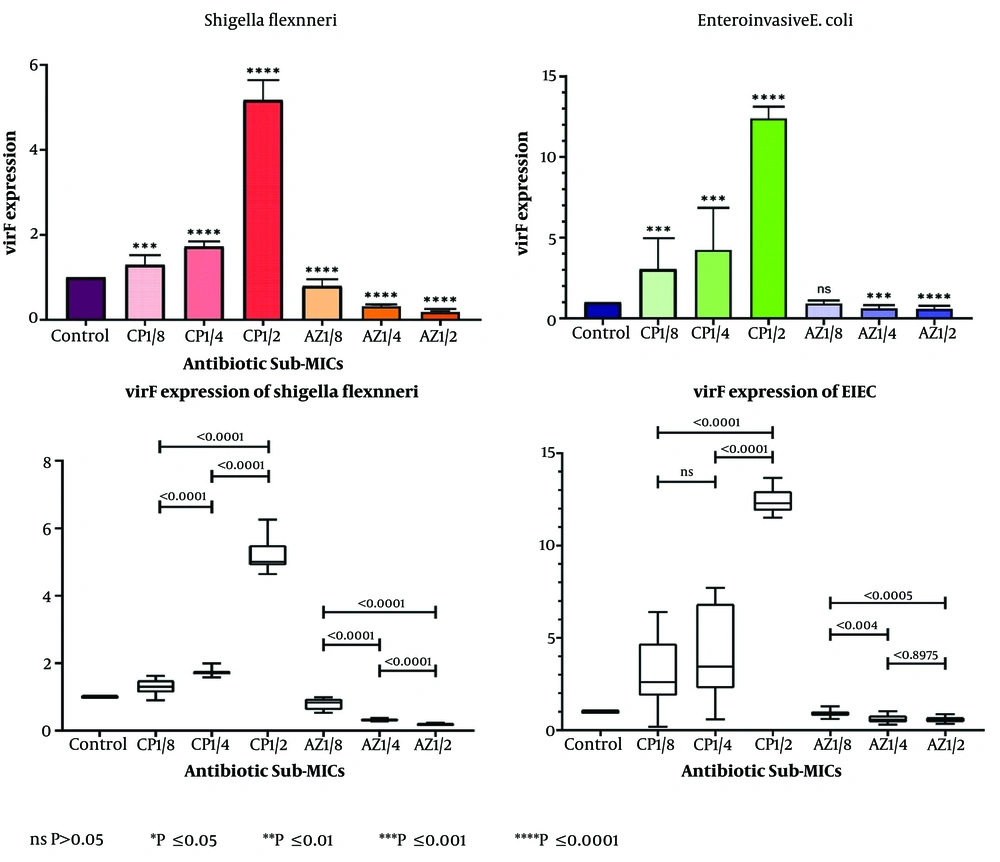

The level of virF expression in S. flexneri control samples (untreated with antibiotics) was significantly higher than in EIEC (Figure 1). The results indicated that both ciprofloxacin and azithromycin altered virF expression in Shigella and EIEC.

- The average expression of virF increased in all samples treated with sub-MICs of ciprofloxacin.

- Conversely, a decrease in virF gene expression was observed in response to sub-MICs of azithromycin in both bacteria.

- The changes in virF gene expression occurred in a dose-dependent manner, with higher concentrations of sub-MICs leading to greater changes (Figure 2).

The expression changes of the virF gene in Shigella flexneri and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) in samples treated with sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs) of ciprofloxacin and azithromycin compared to control samples. The expression of the virF gene in Shigella samples treated with sub-MIC 1.2 of ciprofloxacin was significantly up-regulated compared to the control. Furthermore, a significant increase in expression was observed at concentrations of 1.2 compared to 1.4, and 1.4 compared to 1.8. For EIEC, the highest up-regulation was seen at sub-MIC 1.2. With a significant increase between concentrations of 1.2 and 1.4, but no significant change between sub-MIC 1.4 and 1.8.

These findings suggest that ciprofloxacin sub-MICs enhance bacterial virulence, while azithromycin sub-MICs reduce virulence in both S. Flexneri and EIEC.

The down-regulation of virF in Shigella samples treated with azithromycin was more pronounced at higher sub-MICs compared to the control. In EIEC, a significant reduction in virF expression was observed in samples treated with sub-MICs of 1/2 and 1/4, but no significant decrease was noted at sub-MIC 1/8. Additionally, the decrease in virF expression between sub-MICs of 1/2 and 1/4 was not statistically significant.

Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin had a statistically significant effect on virF expression in EIEC compared to Shigella (P-value < 0.0001), while azithromycin sub-MICs had a significantly greater inhibitory effect on virF expression in Shigella (P-value < 0.0001).

Additional details of the gene expression changes at different sub-MICs are presented in Table 3.

| Strains | Antibiotic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (Sub-MIC) | Ciprofloxacin (Sub-MIC) | |||||

| 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | |

| Shigella flexneri(μg/mL) | ~ 81% ↓ | ~ 69% ↓ | ~ 21% ↓ | ~ 414% ↑ | ~ 72% ↑ | ~ 29% ↑ |

| EIEC (μg/mL) | ~ 42% ↓ | ~ 39% ↓ | ~ 8% ↓ | ~ 1239% ↑ | ~ 422% ↑ | ~ 203% ↑ |

Abbreviations: EIEC, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli; Sub-MIC, sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations.

5. Discussion

The findings of previous studies indicate that sub-MICs of antibiotics can influence bacterial virulence. The results of this study demonstrate that ciprofloxacin and azithromycin sub-MICs affect the expression of the virF gene in S. flexneri and EIEC. While limited studies have evaluated the sub-MIC effects of these antibiotics on Shigella, no previous studies have investigated their effects on EIEC. This study highlights that both ciprofloxacin and azithromycin sub-MICs impact the expression of the upstream regulator virF gene, which controls the expression of many genes involved in bacterial invasion.

The relationship between the expression of different genes in bacterial virulence is a complex process requiring further exploration, particularly through in-vivo studies. Understanding the sub-inhibitory effects of target antibiotics on genes involved in bacterial invasion can aid in predicting bacterial behavior during in-vivo infections and help prevent disease exacerbation due to accessory effects. In a related study by Sadredinamin et al., the virF gene was found to be down-regulated in Shigella serotypes exposed to azithromycin sub-MICs, while up-regulated when treated with ciprofloxacin. Their study also showed that the virB gene was down-regulated when exposed to ciprofloxacin, whereas the icsA gene was up-regulated with azithromycin exposure. Additionally, interactions of Shigella serotypes with the HT-29 cell line were reduced in the presence of azithromycin, but ciprofloxacin exposure yielded variable results (22).

Other studies have shown that sub-MICs of ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole promote the synthesis of Stx in EHEC by inhibiting DNA gyrase and activating the SOS response, increasing the risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in patients (19). Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of azithromycin have also been reported to promote Stx release in E. coli (15), though another study found that azithromycin considerably reduces Stx levels (19).

Additionally, ciprofloxacin sub-MICs have been shown to inhibit UPEC adhesion to epithelial cells by reducing hydrophobicity (16), while enhanced expression of antibiotic resistance genes in Enterococcus faecium was observed in response to ciprofloxacin sub-MICs (20). Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin have also been reported to induce multidrug resistance in E. coli (23).

Conversely, azithromycin sub-MICs have been shown to reduce biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa (17) and increase the growth rate of E. coli (18). These findings underscore the varying effects of sub-MICs of antibiotics on bacterial behavior and highlight the importance of cautious antibiotic use to mitigate unintended consequences.

There is no direct data on the mechanisms by which azithromycin and ciprofloxacin alter the expression of virulence genes in Shigella and EIEC. However, evidence from other studies provides hypotheses about potential mechanisms underlying the sub-MIC effects of these antibiotics.

Bacterial sensory systems frequently respond to environmental stimuli by altering gene expression, allowing cells to adapt to new environments (9). Under antibiotic stress conditions, changes in the expression of genes involved in surface structures, efflux systems, and enzymes associated with antibiotic inactivation have been observed. The regulation of these genes is often controlled by bacterial sensory systems (10, 24).

In this study, a substantial increase in the expression of the virF gene in Shigella and EIEC was observed in response to ciprofloxacin sub-MICs. The virF protein is a major transcriptional regulator of bacterial invasion genes in both species. It is encoded on the invasion plasmid (pInv) and serves as an upstream regulator of other virulence gene regulators such as virB. Most virulence genes encoded by pInv are directly controlled by the virB protein, making the transcriptional activation of operons implicated in invasion dependent on virF expression (25).

Environmental changes such as temperature, pH, and osmolarity are known to influence virF gene regulation, resulting in alterations in bacterial virulence (26). One potential regulatory system linked to virF expression is the CsrA protein, a carbon storage regulator found in E. coli and Shigella. CsrA is involved in cellular metabolism, flagella biosynthesis, and biofilm development. Potts et al. reported that the two-component regulatory system BarA-SirA can promote CsrA expression in response to a reduction in carbon sources like glucose and the accumulation of intermediate metabolites such as fumarate and acetate (27). Gore and Payne demonstrated that bacterial attachment and invasion in cell culture decreased in S. flexneri mutants lacking the csrA gene compared to wild-type strains. They concluded that this reduction in virulence was due to lower virF gene expression in csrA mutants and subsequent down-regulation of pfkA, a gene involved in bacterial glycolysis (28). Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics can induce bacterial stress, enhancing respiration and leading to cell death through the accumulation of toxic compounds such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) (29). High ROS levels are associated with increased glycolysis, which depletes glucose resources and elevates the levels of pyruvate and acetyl-CoA (30). The reduction in carbon sources may induce the expression of CsrA and PfkA proteins, ultimately leading to the up-regulation of the virF gene in bacteria (31, 32).

These findings provide a plausible explanation for the observed up-regulation of virF in response to ciprofloxacin sub-MICs. Further research is needed to validate these mechanisms in Shigella and EIEC. Unlike ciprofloxacin, a down-regulation of the virF gene by sub-MICs of azithromycin was observed in the present study. Bacteriostatic antibiotics, such as azithromycin, inhibit bacterial protein translation. This inhibition can suppress cellular respiration by repressing glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, leading to the accumulation of ADP and AMP, a significant increase in NADH, and a depletion in cellular ATP levels (33). Based on these observations, a hypothesis is proposed: Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics impair the balance of these metabolites, reduce the expression of CsrA and PfkA proteins, and subsequently decrease the expression of the virF gene in these bacteria. However, this hypothesis requires validation through a comprehensive study on bacterial global gene expression.

It has also been suggested that the virF gene is regulated by a protein called YhjC. Li et al. demonstrated that S. flexneri mutants lacking the yhjC gene exhibit reduced adherence to and penetration of host cells. Their study showed that deletion of the yhjC gene down-regulated the expression of virF and all virF-dependent genes. Although the factors influencing the expression of the yhjC gene remain unknown, its expression has been observed to increase when the temperature rises from 30°C to 37°C. These findings suggest that yhjC may be under the control of the two-component regulatory system CpxA/R (34).

In the present study, the temperature, pH, and osmolarity were consistent across all antibiotic-treated and untreated samples, reducing the likelihood that sub-MICs of antibiotics affect virF expression via the CpxA/R system. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms by which azithromycin sub-MICs modulate virF expression, potentially involving yhjC or other regulatory pathways.

In the present study, temperature, pH, and osmolarity were maintained approximately stable in the culture media, minimizing the possibility of stress related to these variables. However, the likelihood of antibiotic-induced stress and its disruption of bacterial metabolism increased. Given the genetic and pathogenic similarities between Shigella and EIEC, this study investigated the effects of sub-MICs of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin on virF gene expression in both bacteria. The similar results observed in both species suggest that these antibiotics may function through common signaling pathways, which could provide valuable insights for future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

Antibiotics have different effects on different bacteria, making it impractical to generalize findings about accessory effects to diverse microorganisms. Evaluating the accessory mechanisms of antibiotics specifically recommended for treating infections caused by particular bacteria is more practical and relevant. The results of this study demonstrate that ciprofloxacin and azithromycin sub-MICs influence the virulence of EIEC and S. Flexneri. These antibiotics are primary options for treating acute infections caused by these bacteria. Unlike ciprofloxacin, azithromycin reduces the severity of infections with these pathogens, even at sub-MICs. Thus, azithromycin may be a more suitable choice for treating bacterial dysentery and mitigating the risk of more severe disease due to improper antibiotic dosing.