1. Background

Surgical site infections (SSIs), as defined by the centers for disease control and prevention (CDC), encompass any post-surgical infection at the operation site. These include superficial incision wounds, deep incision abscesses, and cellulitis (1). Both patient factors and surgical procedures influence SSI development (2). As the most frequent healthcare-associated infections in surgical patients, SSIs represent the most common adverse surgical outcomes (3).

Surgical procedures are classified based on bacterial colonization and contamination levels. Class I (clean surgery) involves procedures limited to skin and soft tissue, including breast and thyroid operations. These typically yield gram-positive cocci from skin flora (4). In specific areas like the perineum or groin, intestinal or genitourinary flora and gram-negative bacilli may be present (4). Class II (clean-contaminated) procedures involve controlled opening of digestive, reproductive, or respiratory systems, such as cholecystectomy and bowel operations (4). Class III (contaminated) procedures involve uncontrolled conditions, such as enterotomy during adhesion surgery (4). Classes II and III commonly isolate endogenous microflora, including aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, yeasts, and fungi (4).

The U.S. centers for CDC reports approximately 500,000 annual surgical wound infections, resulting in increased hospitalization costs, longer stays, and higher mortality rates (5, 6). Infected patients face increased risks: A 60% higher likelihood of ICU admission, five times the chance of rehospitalization, and double the mortality rate compared to uninfected patients (6-8).

Pre-surgical prophylactic antibiotics play a key role in preventing SSIs by reducing microbial presence at the surgical site. Success depends on selecting the right antibiotic, timing, and dosage. The complexities of antibiotic prophylaxis, including resistance concerns and side effects, highlight the importance of following established guidelines (9). The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) clinical practice guideline for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis serves as a primary reference (10).

Guidelines specify that appropriate antimicrobial agents should effectively target SSI-causing organisms, be administered 30 - 60 minutes before incision, and continue for up to 24 hours (10). Multiple studies have assessed compliance with these guidelines' requirements for antibiotic selection, timing, and duration (11-16).

2. Objectives

This study evaluates how closely two Iranian hospitals' surgery departments follow infection prevention guidelines for prophylactic antibiotics.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted at two Iran University of Medical Sciences teaching hospitals in Tehran: Rasool Akram Hospital (April - September 2014) and Firouzgar Hospital (June - December 2022). The study included the general surgery, obstetrics, gynecology, otolaryngology, and orthopedics departments. In teaching hospitals, most surgeries were performed by resident physicians under the supervision of attending physicians, with residents typically responsible for writing preoperative orders.

3.2. Ethical Consideration

The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Iran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (registration ID IR.IUMS.REC.1401.118, approved on 2022/05/22). It incurred no costs to participants, ensured participant confidentiality, and had no financial impact on any individual or organization.

3.3. Sample Size

The study population included patients at both hospitals who received prophylactic antibiotics before surgery. Based on Safargholi et al.'s finding of 50.4% compliance with international guidelines for drug dosage, we calculated a sample size of 100 patients per hospital, using a confidence level of 0.05 and a margin of error of 10% (17).

3.4. Eligibility

We included patients who underwent surgical procedures and received prophylactic antibiotics. Patients with incomplete medical records were excluded from the study.

3.5. Data Collections

We used a two-part form to collect data. The first section recorded patient demographics (age, sex, ward, drug allergy history, and admission reason). The second section documented the antibiotic protocols, including type, dose, pre-operative timing, and prophylaxis duration. We reviewed medical records both before and after operations throughout hospital stays, recording all procedures with clean and clean-contaminated wounds.

We assessed the appropriateness of antibiotic prophylaxis using the ASHP Therapeutic Guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery (10).

3.6. Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the data using IBM SPSS version 26, presenting numerical and nominal variables as mean ± standard deviation.

3.7. Limitations

The limitations of the study included the small sample size, incomplete patient records, and missing information, which led to patient withdrawals from the study.

4. Results

Data from 194 patients were collected across two hospitals: One hundred from Rasoul Akram and 94 from Firouzgar. The sample included 117 male patients (60.3%) and 77 female patients (39.7%). Table 1 presents the demographic information of the patients by hospital.

At Rasool Akram Hospital, clean and clean-contaminated surgeries comprised 43% and 67% of operations, respectively, compared to 11% and 89% at Firouzgar Hospital. The procedures included cholecystectomy, thyroidectomy, herniorrhaphy, diabetic foot surgery, gastrectomy, mandible mass removal, presacral mass removal, ostomy closure, breast mass removal, Whipple surgery, appendectomy, mammoplasty, mastectomy, and soft tissue mass removal. Cholecystectomy was the most common procedure at both hospitals (18% at Rasool Akram and 19% at Firouzgar).

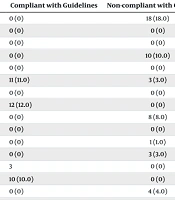

At Rasool Akram Hospital, 90% of prophylactic antibiotic administrations adhered to ASHP therapeutic guidelines. The remaining 10% of cases, primarily thyroidectomies, did not require antibiotic prophylaxis. Among the 90 cases requiring antibiotic prophylaxis, only 39% received the appropriate antibiotic type. Treatment deviations included using multiple antibiotics instead of a single drug (32%), single antibiotic therapy when multiple drugs were indicated (13%), and the selection of incorrect antibiotics (6%). Table 2 displays the surgeons' adherence to ASHP therapeutic guidelines. Nearly all cases had incorrect dosing (95%) and preoperative timing (100%), although the duration of prophylaxis was appropriate in 65% of cases.

| Variables | Antibiotic Administration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasool Akram | Firouzgar | |||

| Type of Surgery | Compliant with Guidelines | Non-compliant with Guidelines | Compliant with Guidelines | Non-compliant with Guidelines |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 0 (0) | 18 (18.0) | 0 (0) | 18 (19.1) |

| Open cholecystectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Rectosigmoidoscopy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (12.8) | 0 (0) |

| Thyroidectomy | 0 (0) | 10 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.3) |

| Colectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.5) | 0 (0) |

| Herniorrhaphy | 11 (11.0) | 3 (3.0) | 9 (9.6) | 0 (0) |

| Esophagectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.3) |

| Diabetic foot surgery | 12 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrectomy | 0 (0) | 8 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.5) |

| Lung resection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.2) | 0 (0) |

| Mandibular mass excision | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Presacral mass excision | 0 (0) | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ostomy closure | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Breast mass excision | 10 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Whipple procedure | 0 (0) | 4 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.3) |

| Mammectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.2) |

| Appendectomy | 0 (0) | 12 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.2) |

| Colocolic anastomosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0) |

| Hepatectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) |

| Mammoplasty | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Bariatric surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

| Soft tissue mass excision | 0 (0) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrojejunostomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 39 (39.0) | 61 (61.0) | 39 (41.5) | 55 (58.5) |

Antibiotic Prescription Compliance Rates with American Society Of Health-System Pharmacists Guidelines Across Surgical Procedures a

Both hospitals deviated from ASHP guidelines by using oral antibiotics for prophylaxis instead of the recommended injectable forms. At Firouzgar Hospital, none of the antibiotic doses adhered to the guidelines, and appropriate drug selection occurred in only 41.5% of cases (39 patients).

Across both hospitals, incorrect antibiotic dosing occurred in 79.8% of cases, with improper preoperative timing in 97.4% of cases at Rasool Akram Hospital and 100% at Firouzgar Hospital. Only 33% of cases adhered to the recommended prophylaxis duration.

5. Discussion

Wound infection remains a significant cause of complications and mortality in surgical patients, despite prophylactic antibiotic use (18). Multiple factors contribute to the risk of wound infection, including surgical wound classification, technique, incision type, tissue damage, wound edge tension, retained foreign bodies or necrotic material, incomplete hemostasis, BMI, underlying medical conditions, and smoking (19).

Antibiotic prophylaxis is required when bacterial wound contamination is possible, when prostheses are inserted, or when infection could lead to serious complications in clean surgeries (20). While prophylactic antibiotics have reduced post-surgical infection rates, their improper use presents ongoing challenges, including adverse drug reactions, bacterial resistance development, and unnecessary hospital costs. A common error is the use of broad-spectrum antibiotic combinations instead of targeted single antibiotics (21).

This study documented current surgical practices at tertiary hospitals and their alignment with ASHP therapeutic guidelines. The findings provide evidence for improving local healthcare practices and rational antibiotic prophylaxis use in surgery. While ASHP therapeutic guidelines effectively minimize SSI rates (16, 17, 22-26), research shows that inadequate prophylaxis protocols and poor compliance with recommended practices remain significant issues.

Afhami et al. studied 172 patients receiving pre-surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and found appropriate prescription methods in only one-quarter of the cases. They concluded that implementing standardized protocols, resident training, and antibiotic prescription monitoring systems was necessary for effective prophylactic antibiotic use (23).

In another Tehran hospital study, Safargholi et al. evaluated prophylactic antibiotic administration against international guidelines (17). Of 252 cases, 75.8% had appropriate indications for prophylactic antibiotics. Correct antibiotic selection occurred in 50.4% of cases, while appropriate duration and dosage were found in 19.4% and 30.6% of cases, respectively (17). Our study found 90% compliance with ASHP guidelines for antibiotic indications, with only 10% of procedures lacking prophylactic indications. However, only about 40% of patients received the correct antibiotic type, with most surgeons choosing non-recommended combination therapy. At Rasool Akram Hospital, 95% of cases had incorrect dosing, and 100% had incorrect preoperative timing, while Firouzgar Hospital showed 100% incorrect rates for both measures. Prophylaxis duration was correct in 65% of Rasool Akram Hospital cases but incorrect in all Firouzgar Hospital cases.

The findings from both hospitals reveal no significant improvement in prescribing standards over nine years, despite their shared training center affiliation. This stagnation highlights the need for a structured program combining comprehensive training with regular antibiotic stewardship monitoring, including oversight of non-broad-spectrum antibiotics.

A study by Laali et al. at the Cancer Institute of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran reported a 31% surgical site infection rate after 30 days. They found substantial non-compliance with guidelines: 63.7% for antibiotic selection, 98.4% for dosage, and 39.5% for prophylaxis timing. These results underscore the importance of hospital-specific compliance monitoring (24).

The data shows that surgeons continue to deviate significantly from international guidelines, leading to drug reactions, increased bacterial resistance, and unnecessary hospital costs.

To address these issues, hospitals should establish dedicated teams of infectious disease physicians, surgeons, and clinical pharmacists. The infection control committee should regularly assess compliance with antimicrobial prophylaxis guidelines (12, 27-29). Ongoing education through conferences and workshops is essential, with clinical pharmacists and infectious disease specialists developing and distributing guidelines through drug committees and informational materials. Medication distribution programs should operate under clinical pharmacist supervision to promote appropriate use. Regular assessment of clinician practices would also be beneficial.

Current guidelines advise against prophylactic antibiotics in clean (class I) surgeries (10). However, both hospitals administered prophylactic antibiotics to all patients in this category, indicating a lack of understanding about surgical classifications and their corresponding antibiotic prophylaxis requirements.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study reveals that surgeons' knowledge of appropriate prophylactic antibiotic selection and dosing remains inadequate when measured against standard guidelines. This knowledge gap leads to antibiotic misuse and excessive hospital costs.

The findings highlight significant issues in prophylactic antibiotic prescribing practices. Injectable antibiotic doses were incorrect in all cases, with doses exceeding guideline recommendations even when the correct antibiotic was selected. Both medical centers consistently prescribed prophylactic antibiotics at levels above guideline recommendations.

These problems, along with inconsistencies in oral antibiotic prescribing, underscore the need for enhanced training and better oversight of prophylactic antibiotic use in surgical settings.